CHAPTER VII

HOW WULF CLIMBED THE IVY TOWER, AND WHAT HE SAW AT THE BARRED WINDOW

Good as his word had Herr Werner been in finding Wulf the chance to show that other stuff dwelt in him than might go to the making of a mere stable-lad. For the next three years he was under the young knight’s helping protection, and, thanks to the latter’s good offices in part, but in the end, as must always be the case, with boy or man, thanks to his own efforts, he made so good use of his chance that his tinker origin was haply overlooked, if not forgotten, by those left behind him as he mounted height by height of the castle’s life.

Not that these forgave him his rise. Those small, mean souls had sought the hurt of the boy, but, when all was said and done, ’twas hard to hold hatred of such a nature as his. The training of old Karl and of the forest had done its work well with him, and he was still the simple, sunny-hearted Wulf of the forge, ever ready to help, forgiving even where forgiveness was unsought, and keeping still, amid all the foulness and wickedness of that dark time and in that evil place, the clean, wholesome child nature that had dwelt in the baby among the osiers.

He was by now a sturdy, broad-chested young fellow, getting well on to manhood, noted for his strength, and for his skill in all the games and feats of prowess and endurance that were a part of the training of boys in those days. Already had he ridden with Herr Werner in battle, and though no real armiger, by reason of his lowly birth, yet was he, in the disorder of the times, unchallenged as the knight’s chosen attendant and buckler-bearer on the lawless raids on which the baron led his train. Indeed, the baron himself had more than once taken note of the youth, and had on two occasions made him his messenger on errands both perilous and nice, calling for wit as well as bravery.

Only Conradt hated him still—Conradt, with the sorry, twisted soul that held to hatred as surely as Wulf held to love. He was a year or two older than Wulf, and was already a candidate for knighthood; for, despite his crooked body, he was skilled, beyond many who rode in his uncle’s following, in all play at arms. There was no better swordsman even among the younger knights, and among the bowmen he had already a name.

Despite all this, however, the baron’s nephew was held in light esteem, even among that train of robbers and bandits—for naught better were they, in truth, despite their knighthood and their gentlehood. They lived by foray and pillage, and petty warfare with other bands like themselves, and in many a village were dark stories whispered of their wild raids.

Yet none of these would hold fellowship with Conradt, albeit they dared not openly flout the baron’s nephew. Nevertheless, he had gathered to himself a manner of following from the villages and countryside about the Swartzburg: criminals and refugees, for the most part, men who had suffered for their misdeeds at the hands of such law as was in the land; fellows whom no other leader would own, but who gladly fell in under a headship as bad as they. These ranged the forest wide and far, and from their evil raids was no poor man free nor helpless woman safe.

Well knew the baron, overlord of all that district, of the doings of his doughty nephew; but for reasons of his own he saw fit to wink at them, save when some worse infamy than common was brought to his notice in such fashion that he could not pass it by. He were a brave man, however, who could dare the baron’s wrath so far as to complain lightly to him of Conradt, so the fellow went for the most part scot-free of his misdeeds, save so far as he might feel the scorn and shunning of his equals.

It was on a bright autumn afternoon that a company of the boys and younger men of the Swartzburg were trying feats of strength, and of athletic skill, before the castle, in the inner bailey. From a little balcony overlooking the terrace the ladies of the household looked down upon the sports, to which their presence gave more than ordinary zest. Among the ladies was Elise, now grown a fair maiden of some fifteen years. Well was she known to be meant by the baron for the bride of his nephew; but this knowledge among the youths of the place did not hinder many a quick glance from wandering her way, and already had more than one young squire chosen her as the lady of his worship, for whose sake he pledged himself, as the manner of the time was, to deeds of bravery and high virtue.

The contestants in the courtyard had been wrestling and racing; there had been tilts with the spear, and bouts with the fists, and some sword-play, when at last one of the number challenged his fellows to a climbing trial of the hardest sort.

Just where the massive square bulk of the keep raised its grim stories, a great buttress thrust boldly out from the castle, running up beside the wall of the tower for a considerable distance. The two were just enough apart to be firmly touched, on either side, by a man who might stand between them, and it was a mighty test of courage and strength for a man to climb up between them, even a few yards, by hand and foot pressure only. It was a great feat to perform among the more ambitious knights and squires about the castle.

The challenger on this afternoon was young Waldemar Guelder, Herr Banf’s ward, now grown a stalwart squire; and he raised himself, by sheer strength of grip and pressure of foot and open hand against the rough stones, up and up, until he reached the point, some thirty feet above ground, where the buttress bent in to the main wall again, and gave no further support to the climber, who was fain to come down by the same way as he went up.

Shouts of “Well done! Well done!” greeted Waldemar’s deed when he reached the ground, panting, but flushed with pride, and looked up toward the balcony, whence came a clapping of fair hands and waving of white kerchiefs in token that his prowess had been noted.

Then one after another made trial of the feat; but none, not even Conradt, who was accounted among the skilfulest climbers, was able to reach the mark set by young Guelder, until, last of all, for he had given place time after time to his eagerer fellows, Wulf’s turn came.

He too glanced up at the balcony as he began the ascent, and Elise, meeting his glance, smiled down upon him. These two were good friends, in a frank fashion little common in that time, when the merest youths deemed it their duty to throw a tinge of sentimentality into their relation with all maids.

Conradt noted their glances, and glowered at Wulf as the latter prepared to climb. No sneer of his had ever moved Elise to treat “the tinker” with scorn. Indeed, Conradt sometimes fancied that her friendship for Wulf was in despite of him and of the mastership he often tried to assert over her. That, however, was impossible to an honest nature like Elise. She was Wulf’s friend because of her hearty trust in him and liking for him, and so she leaned forward now, eager to see what he might do toward meeting Waldemar’s feat.

Steadily Wulf set hands and feet to the stones, and braced himself for the work. Reach by reach he raised himself higher, higher, until it was plain to all that he would find it no task to climb where the champion had done.

“He’ll win to it!” cried one and then another of the watchers, and Waldemar himself shouted out encouragement to the climber when once he seemed to falter. At last came a cry from Hansei: “He has it! Hurrah!” and a general shout went up. From the balcony, too, came the sound of applause as Wulf reached the top of the buttress.

“In truth, our tinker hath mounted in the world,” sneered Conradt from the terrace. “Well, there’s naught more certain than that he’ll come down again.”

Wulf heard the words, as Conradt meant he should, and caught, as well, the laugh that rose from some of the lower fellows. Then a murmur of surprise went through the company.

The walls of the keep were overgrown with ivy, so that only here and there a mere shadow showed where a staircase window pierced the stones. In the recess where the young men were wont to climb the vines were torn down, but above the buttress, over both keep and castle, the great branches grew and clung, reaching clean to the top of the tower; and Wulf, unable to go farther between the walls, was now pulling himself up along the twisted ivy growth that covered the face of the tower.

On he went, minded to reach the top and scale the battlement. It was no such great feat, the lower wall once passed, but none of the watchers below had ever thought to try it, so were they surprised into the more admiration, while in the balcony was real fear for the adventurous climber.

He reached the top in safety, however, and passing along the parapet just below the battlement, turned a corner and was lost to their sight.

On the farther side of the keep he found, as he had deemed likely, that the ivy gave him safe and easy support to the ground, so lowering himself to the vines again, he began the descent.

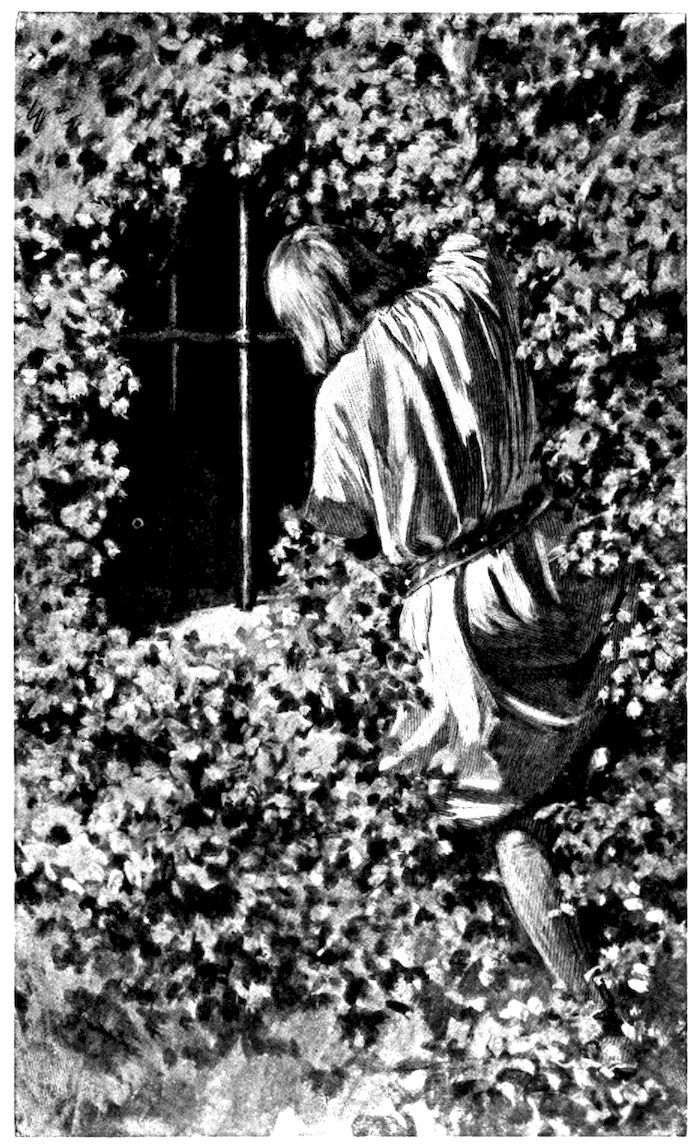

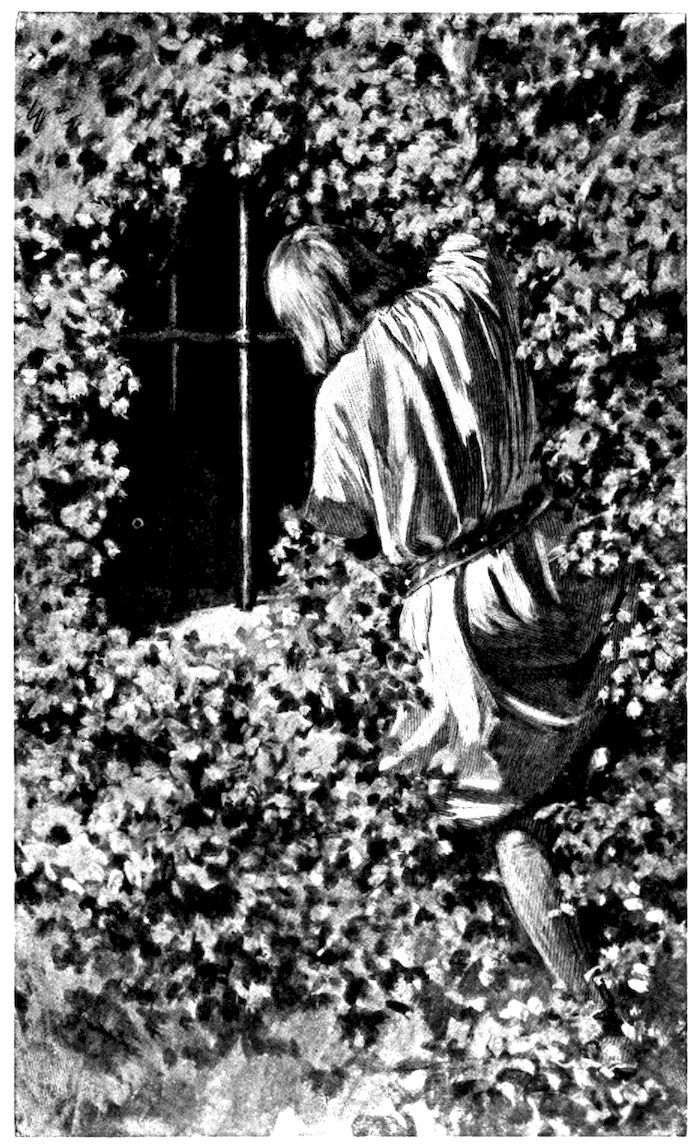

He had gone but a little way when, feeling with his feet for a lower hold, he found none directly under him, but was forced to reach out toward the side to get it, from which he judged that he must be opposite a window, and lowering himself farther, he came upon two upright iron bars set in a narrow casement nearly overgrown with ivy. Behind the bars all seemed dark; but as Wulf’s eyes became wonted to the dimness, he became aware, first of a shadowy something that seemed to move, then of a face gaunt, white, and drawn, with great, unreasoning eyes that stared blankly into his own.

“LOWERING HIMSELF FARTHER, HE CAME UPON A NARROW CASEMENT NEARLY OVERGROWN WITH IVY.”

He felt his heart hammering at his ribs as he stared back. The piteous, vacant eyes seemed to draw his very soul, and a choking feeling came in his throat. For a full moment the two pairs of eyes gazed at each other, until Wulf felt as if his heart would break for sheer pity; then the white face behind the bars faded back into the darkness, and Wulf was ware once more of the world without, the yellow autumnal sunshine, and the green ivy with its black ropes of twisted stems, that were all that kept him from dashing to death on the stones of the courtyard below.

So shaken was he by what he had seen that he could scarcely hold by his hands while he reached for foothold. Little by little, however, he gathered strength, and came to himself again, until by the time he reached the ground he was once more able to face his fellows, who gathered about, full of praise for his feat.

But little cared our Wulf for their acclaim when, glancing up toward the balcony, he caught the wave of a white hand. His heart nearly leaped from his throat, a second later, as he saw a little gleam of color, and was aware that the hand held a bit of bright ribband which presently fluttered over the edge of the balcony and down toward the terrace.

It never touched earth. There was a rush toward it by all the young men, each eager to grasp the token; but Wulf, with a leap that carried his outstretched hand high above the others, laid hold upon the prize and bore it quickly from out the press.

“’Tis mine! Yield it!” screamed Conradt, rushing after him.

“Nay; that must thou prove,” laughed Wulf, and winning easily away from the hunchback, he ran through the inner bailey to his own quarters, whence, being busy about some matters of Herr Werner’s, he came forth not until nightfall. At that time Conradt did not see him; for the baron had summoned his nephew to him about a matter of which we shall hear more.