CHAPTER III

HOW WULF FARED AT KARL THE ARMORER’S HUT

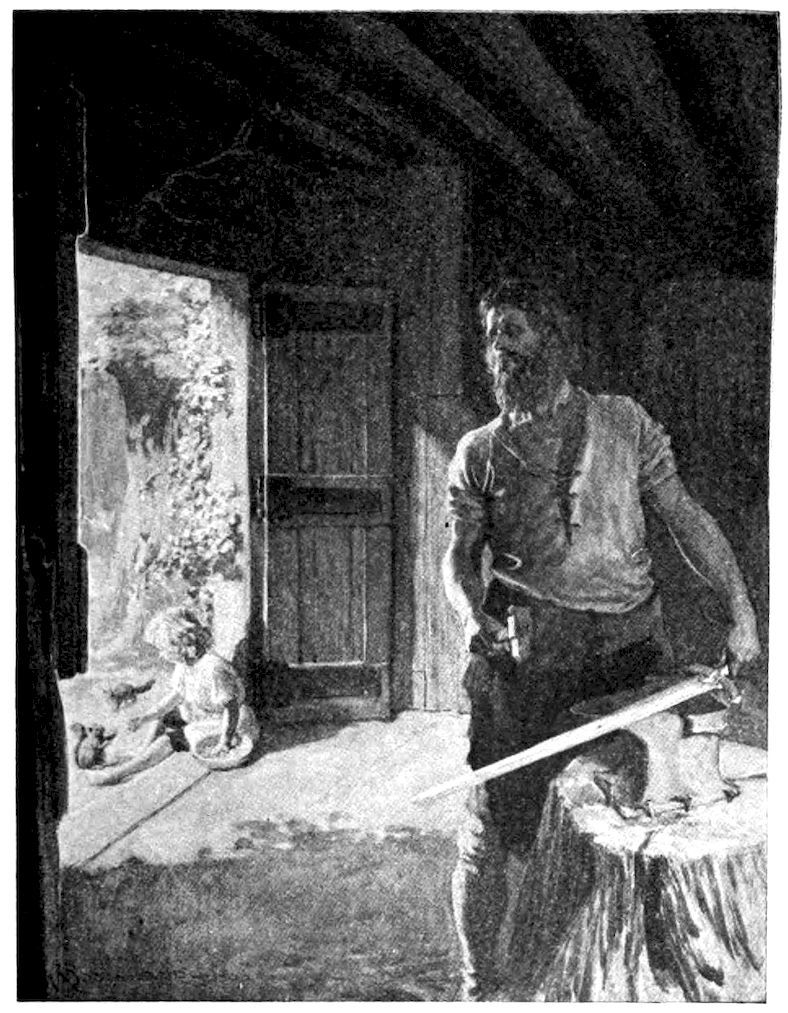

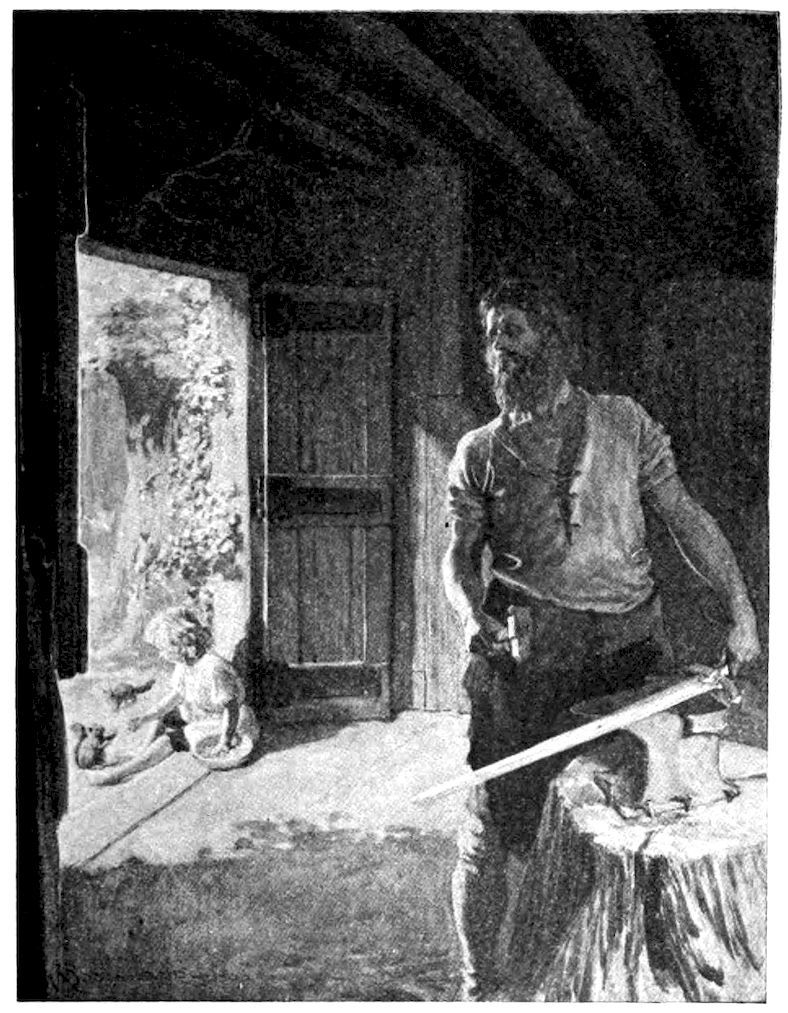

Big Karl the armorer was busy at his forge, next morning, long before his wee guest awakened from the deep sleep of childhood, which he slept upon a pile of pelts in a corner of the smithy. Working with deft lightness of hand at a small, long anvil close beside the forge, Karl had tempered and hammered the broken point of Herr Banf’s sword until the stout blade was again ready for yeoman service, and then he turned to the stranger knight’s blade, which was broken somewhat about the hilt and guard.

It was a good weapon, and as Karl traced his finger thoughtfully down its length he turned it toward the open door, that the early sunlight might catch it. Then he suddenly gave a start, and hastily carried the sword out into the full daylight, where he stared it over closely from hilt to point, turning it this way and that, with knit brows and a look of deep sorrow on his browned visage. After that he strode into the smithy, and went over to where the boy lay, still fast asleep.

Turning him over upon the pelts, he studied the little face as sharply as he had done the sword, noting the broad white brow, the delicate round of the cheek, and the set of the chin, firm despite its baby curves; and as he did so a great sternness came over the face of the armorer.

“There’s some awful work here,” he said at last to himself. “Heaven be praised I came upon the little one! Would that I might have had a look at the face of that big knight.”

Still musing, he turned and went to a cleverly hid cupboard in the wall beside the great chimney. Opening this, he disclosed an array of blades of many sorts and shapes, and from among these he took one that in general appearance seemed the fellow of the stranger’s weapon, save that it had, to all look, seen but scant service in warfare.

Karl compared the two, and then set to a strange task. Hanging the service-battered sword naked within the cupboard, he took the new blade and began to ill-treat it upon his anvil—battering the hilt, taking a bit of metal from the guard, and putting nicks into the edge, only to beat and grind them very carefully out again. He took a bottle of acid from a shelf and spilled a few drops where blade met hilt, wiping it off again when it had somewhat stained and roughened the steel. This roughness he afterward smoothed away, and worked at the sword until he had it in fair semblance of a hardly used tool put in good order by a skilful smith.

This done he sheathed it in the scabbard which the stranger had worn, and which was a fair sheath, wrought with gold ornaments cunningly devised. Karl looked at it with longing.

“I’d like well to save it for ye, youngster,” he said; “but ’tis a fair risk as it stands. Let Herr Ritter Banf alone for having spied the gold o’ this sheath; it must e’en go back to him.” He laid the sheathed weapon away in a chest with Herr Banf’s own until such time as he should make his next trip to the castle.

He had hardly done when, turning, he beheld the child watching him from the pile of skins, looking at the strange scene about him, but keeping quiet, though the tender lips quivered and the look in the blue eyes filled Karl with pity.

“There’s naught to fear, little one,” he said with gruff kindness, lifting the boy from the pile. “I make sure you’re hungry by now, and here’s the remedy for that—and for fear, too, of your sort.” And from out the coals of the forge he drew a pannikin, where it had been keeping warm some porridge.

Very gently he proceeded to give it to the child, with some rich goat’s milk to help it along. In truth, however, it needed not that to give the boy an appetite. He had eaten nothing the night before, seeming starved for sleep, but now he ate in a half-famished way that touched Karl’s heart.

“In sooth, now,” the latter said, watching him, “thou’st roughed it, little one, and much I marvel what it all may mean. But one thing sure, this is no time to be asking about the farings of any of thy breed, so thou shalt e’en bide here with old Karl till these evil days lighten, or Barbarossa comes to help the land—if it be not past helping. It’ll be hard fare for thee, my sweet, but there’s no doing other. The castle yonder were worse for thee than the forge, here, with Karl.”

“Karl?” The child spoke with the fearless ease of one wonted, even thus early, to question strangers, and to be answered by them.

“Ay, Karl,” replied the armorer. “Karl, who will be father and mother to thee till such time as God sends thee to thine own again.”

“Good Karl,” said the baby, when the man ceased speaking, and he reached out his hands to the armorer. The latter lifted him and carried him to the forge door.

“Thou’rt a sturdy rascal,” he said, nodding approval of the firm, well-knit little figure. “Sit thou there and finish the porridge.”

The little fellow sat in the wide door of the smithy and ate his coarse food with a relish good to see. It was a rough place into which he had tumbled—how rough he was too young to realize; but much worse, even of outward things, might have fallen to his share, as, indeed, we shall see ere we have finished with young Wulf.

Deep within the heart of each one of us, no matter how old, there lives a child. All our strength, all that the years bring us of gain or good, help us not at all if these do not serve to fend this child from harm, and to keep it good. Big Karl at his forge knew naught of books, and to him, in those evil days, had come much knowledge of the cruelty and wickedness of evil men. Nevertheless, safe within his strong nature dwelt the child-soul, unhurt by all these. It looked from his honest blue eyes, and put tenderness into the strength of his great hands when he touched the other child, and this child-soul was to be the boy’s playmate through the years of childhood. A wholesome playmate it was, keeping Wulf company cleanly-wise, and no harm came to him, but rather good.

“THE FOREST’S SMALL WILD LIFE CONSTANTLY CAME IN AT THE OPEN DOOR.”

Then, beside the ministering care of the gentle, manly big armorer, little Wulf had through those years the teaching and companionship of the great forest. It grew close up about the shop, so that its small wild life constantly came in at the open door, or invited the youngster forth to play. Rabbits and squirrels peeped in at him; birds wandered in and built their nests in dark corners; and one winter a vixen fox took shelter with them, remaining until spring, and grew so tame that she would eat bread from Wulf’s hand.

The great trees were his constant companions and friends, but one mighty oak that grew close beside the door, and sent out its huge arms completely over the shop, became, next to Karl, his chosen comrade. Whenever the armorer had to go to village or castle, Wulf used to take shelter in this tree; not so much from fear,—for even in those evil days the armorer’s grandson, as he grew to be regarded by those who came about the forge, was too insignificant to be molested,—but because of his love for the great tree. As he became older he was able to climb higher and higher among its black arms, until at last he made him a nest in the very crown of the wood giant.

Every tree, throughout its life, stores up within its heart light and heat from the sun. It does this so well, because it is its appointed task in nature, that the very life and love that the sun stands for to us become a part of its being, knit up within its woody fiber. When we burn this wood in our stoves or our fireplaces, the warmth and blaze that are thrown out are just this sunshine which the tree has caught in its heart from the time it was a tiny seedling till the ax was laid at its root. So when we sit by the coal fire and enjoy its genial radiance, we are really warming ourselves by some of the same sunlight and warmth that sifted down through the leaves of great forest trees, perhaps thousands of years ago.

Of course little Wulf did not know all this as we know it, but doubtless he knew much else that we do not know at all; at all events, he knew the sunshine of his own time and his own forest, and into his sound young heart there crept, as the years went by, somewhat of the strength and the sunshine-storing quality of his forest comrade, until, long before he became a man, those who knew him grew to feel that here was a strong, warm heart of human sunshine, ready to be useful and comforting wherever use and comfort were needed.

At first faint memories haunted him; but as the years passed he learned to think of them as a part of one of Karl’s stories—one that he always meant to ask him to tell again, sometime. The years slipped away, however, and his childish impressions grew fainter and fainter, until at last they had quite faded into the far past.

But all this came about years after, and could not possibly have been foreseen by Karl the armorer as he stood at his forge and thought sadly on his own inability to do all that needed doing for the little one so suddenly and so strangely thrust upon his care.