CHAPTER IV

OF HOW WULF FIRST WENT TO THE CASTLE, AND WHAT BEFELL

For a matter of nine or ten years Wulf dwelt with Karl at the forge, and knew no other manner of finding than if he had been indeed the armorer’s own grandson, as he was known to those who took the trouble to wonder, Karl himself never dissenting to the idea. He was now a well grown lad of perhaps fourteen years, not tall, but sturdy, strong of thigh and arm, good to look at, with a ruddy color, fair hair, and steady eyes that met the gaze fearlessly.

Karl had taught him to fence and thrust, and much of sword-play, in which the armorer was skilled, and while his play at these was that of a lad, the boy could fairly hold his own with cudgel and quarter-staff, and more than once had surprised Karl by a clever feint or twist or a stout blow, when, as was their wont on summer evenings, the two wrestled or sparred together on the short green grass under the great oak-tree. Also, Wulf was beginning to be of use at the forge, and great was his joy when, after repeated attempts, he at last made for himself a knife of excellent temper and an edge which even Karl found good. Thereafter this knife was his belt companion in all his woodland journeys.

He was happy, going about his work with the big armorer, or wandering up and down the forest, or, of long winter evenings, sitting beside the forge fire watching Karl, who used to sit, knife in hand, deftly carving a long-handled wooden spoon, or a bowl. The women in the village were always glad to trade for these with fresh eggs, or a pat of butter, or a young fowl; for the armorer had as clever a knack with his knife as with his hammer. On these evenings he used to fill the boy’s spirit with joy by tales of knightly craft, and of the brave gentlemen who, in years past, had ridden to the holy wars, and of deeds of gentleness and courage done by brave knights for country and king and the truth. Then it was that young Wulf felt his heart glow within him, and he longed for the time when he too might fare out to fight for the good, and to free the land from the evil that wasted field and meadow and ground down the people until no man dared hold up his head or meet, level-eyed, the gaze of his fellow.

It happened, at last, on a day when Karl was making ready to go to the castle with a corselet which he had mended for the baron himself, that the armorer met with an accident that changed Wulf’s whole life. Karl was doing a bit of tinkering on the smaller anvil by the forge, when one support of the iron gave way, and it fell, crushing the great toe of one foot so that the stout fellow fairly rocked with the pain, while Wulf made haste to prepare a poultice of wormwood for the hurt member.

Despite all their skill, however, the toe continued to swell and to stiffen, until it was plain that all thought of Karl’s climbing the mountain that day, or for many days to come, must be put aside.

“There’s no help for it, lad,” he said at last, as he sat on the big chest scowling blackly at his foot in its rough swathings. “It’s well on toward noon now, and the baron will pay me my wage on my own head if his corselet be not to hand to-day; for he rides to-morrow, with a company from the castle, on an errand beyond. Thou’lt need to take the castle road, boy, and speedily, if thou’rt to be back by night.”

Nothing could have pleased Wulf more than such an errand; for although he often went with Karl on other matters about the country, and had even gone with him as far as the Convent of St. Ursula on the other side of the forest, the armorer, despite his entreaties, had never allowed him to go along when his way lay toward the Swartzburg. This had puzzled the boy greatly, for Karl steadfastly refused him any reason why it should be. In truth Karl could hardly have given reason even to himself for his action. His unwillingness to take Wulf to the castle was, however, really grounded upon a fear of what as yet unknown thing might happen.

The boy made all haste, therefore, to get ready for the journey, lest Karl should repent of his plan. It was but the shortest of quarter-hours, in fact, before—his midday meal in a wallet at his belt, the armorer’s iron-shot staff in his hand, and the corselet slung over his shoulder—he was passing through the wood toward the road to the Swartzburg.

Walking with the easy swing of one well wonted to the exercise, it was not so very long ere he had cleared the forest and was stepping up the rough stone road that climbed the mountain pass to the castle. He crossed the stream at a point very near the clump of willows below the plateau where, years before, the children had watched the shining knight’s encounter with Herr Banf. Other children played on the plateau, as the little ones had done that fair morning, but Wulf hastened on, mindful only of the new adventure that lay before him.

Up and up the stony way he trudged stoutly, until it became at last the merest bridle-path, descending to the open moat across which the bridge was thrown. On a tower above he descried the sentry, and below, beyond the bridge, the great gates into the castle garth stood open.

Doubting somewhat as to what he ought to do, he crossed the bridge and passed through the gloomy opening that pierced the thick wall. Once inside, he stood looking about him curiously, forgetful, in his wonder and delight at the scene, that Karl had told him to ask for Gotta Brent, Baron Everhardt’s man-at-arms, and to deliver the corselet to him. This, by now, he had slipped from his shoulder and held with his arm thrust through its length, his fingers grasping its lower edge.

He was still without the inner wall of the castle, in a sort of courtyard of great size, the outer bailey of the stronghold. Beyond where he stood he could see a second wall with big gates similar to the one through which he had just passed. Before these gates in the outer court two young men were fencing, while a third stood beside them, acting as a sort of umpire or judge of fence. The contestants were very equally matched, and Wulf watched them with keenest enjoyment. He had fenced with Karl, and once or twice a knight, while waiting at the forge, had deigned to pass the time in crossing blades with the boy, always to the latter’s discomfiture; but he had never before stood by while two skilled men were at sword-play, and the sight held him spellbound.

Thanks to Karl, he was familiar with the mysteries of quart and tierce and all the rest, and followed with knowing delight each clever feint and thrust, made with the grace and precision of good fence. He could watch forever, it seemed to him; but as he stood thus, following the beautiful play, out through the gate of the inner bailey came three children—a girl a year or two younger than he, and two boys about his own age.

He gave them but the briefest glance, for just at that moment the players began a new set-to, and claimed his attention. In a little bit, however, he felt a sharp buffet at side of the head, and, turning, saw that one of the boys had thrown the rind of a melon so as to strike him on the cheek. As Wulf looked around, both the boys were laughing; but the little girl stood somewhat off from them, her eyes flashing and her cheeks aglow as with anger. She said no word, but looked with great scorn upon her companions.

“Well, tinker,” called the boy who had thrown the melon-rind, “mind thy manners before the lady! Have off thy cap or thou’lt get this,” and he grasped the other half-rind of melon, which the second boy held.

“Nay, Conradt!” the little maid cried, staying his hand. “The lad is a stranger, and come upon an errand; do we treat such folk thus?”

Wulf’s cap was by now in his hand, and, with crimson cheeks, he made a shy salutation to the little girl, who returned it courteously, while the boys still laughed.

“What dost thou next, tinker?” the one whom she had called Conradt said, strutting forward. “Faith, thy manners sorely need mending. What dost to me?”

“Fight you,” said Wulf, quick as a flash, and then drew back, abashed; for, as the boy came forward, he saw that he bore a great hump upon his twisted back, while one of his shoulders was higher than the other.

The deformed boy saw the motion, and his face grew dark with rage and hate.

“Thou’lt fight me?” he screamed, springing forward. “Ay, that thou shalt, and rue it after, tinker’s varlet that thou art!” And with his hand he smote Wulf upon the mouth, whereupon he dropped the corselet and clenched his fists, but could lay no blow on the pitiful creature before him. Seeing this, the other, half crazed with anger, drew a short sword which he wore, and made at Wulf, who raised the armorer’s staff which he still held and struck the little blade to the ground.

By now the two fencers and their umpire were drawn near to see the trouble, and one of them picked up the sword.

“Come, cockerel,” he said, restoring it to him, “put up thy spur and let be. Now, lad, what is the trouble?” and he turned sharp upon Wulf.

“’Tis the armorer’s cub,” he said to his companions as he made him out. “By the rood, lad, canst not come on a small errand for thy master without brawling in this fashion in the castle yard? Go do thy message and get about home, and bid thy master teach thee what is due thy betters ere he sends thee hither again.”

“Yon lad struck me,” Wulf said stoutly. “I’ve spoken no word till now.”

“Truly, Herr Werner,” put in the little girl, earnestly, “it is as he says. Conradt has e’en gone far out of his way to show the boy an ill will, though he has done naught.”

At this Herr Werner looked again upon Conradt. “So, cockerel,” he said. “Didst not get wisdom from the last pickle I pulled thee out of?”

“Why does the fellow hang about here, then?” demanded Conradt, sulkily. “Let him go to the stables, as he should, and leave his matter there.”

“I was to see Gotta Brent,” Wulf said, ignoring Conradt and speaking to the young knight.

“See him ye shall,” was the reply. But anything further that Herr Werner might have said was cut short by the sound of a great hue and cry of men, and a groom ran through the gate shouting:

“Back! Back for your lives! The foul fiend himself is loose here!”

At his heels came half a dozen men, with stable forks and poles, and two others who were hanging with all their weight upon the bridle-reins of a great horse that was doing his best to throw off their hold, rearing and plunging furiously, and now and again lashing out with his iron-shod hoofs.

There was a hurrying to shelter of the group about Wulf, who stood alone now, staring at the horse. The latter finally struck one of the grooms, so that the fellow lay where he rolled, at one side of the court, and then began a battle royal between horse and men.

One after another, and all together, the men tried to lay hold upon the dangling rein, only to be bitten, or struck, or tossed aside, as the case might be, until at last the huge beast stood free, in the middle of the court, while the grooms and stable-hangers made all haste to get out of the way, some limping, others rubbing heads or shoulders, and one nursing a badly bitten arm.

“Tinker,” called the knight from behind an abutment of the wall, “art clean daft? Get away, before he makes a meal off thee! Gad! ’twill take an arrow to save him now; and for that any man’s life would be forfeit to Herr Banf.”

There was a scream from the little girl; for the horse had spied Wulf, and came edging toward him, looking wild enough, with ears laid back and teeth showing, as minded to make an end to the boy, as, doubtless, he was. For the life of him Wulf could not have told why he was not afraid as he stood there alone, and with no weapon save the armorer’s staff, which he had not time to raise ere the beast was upon him.

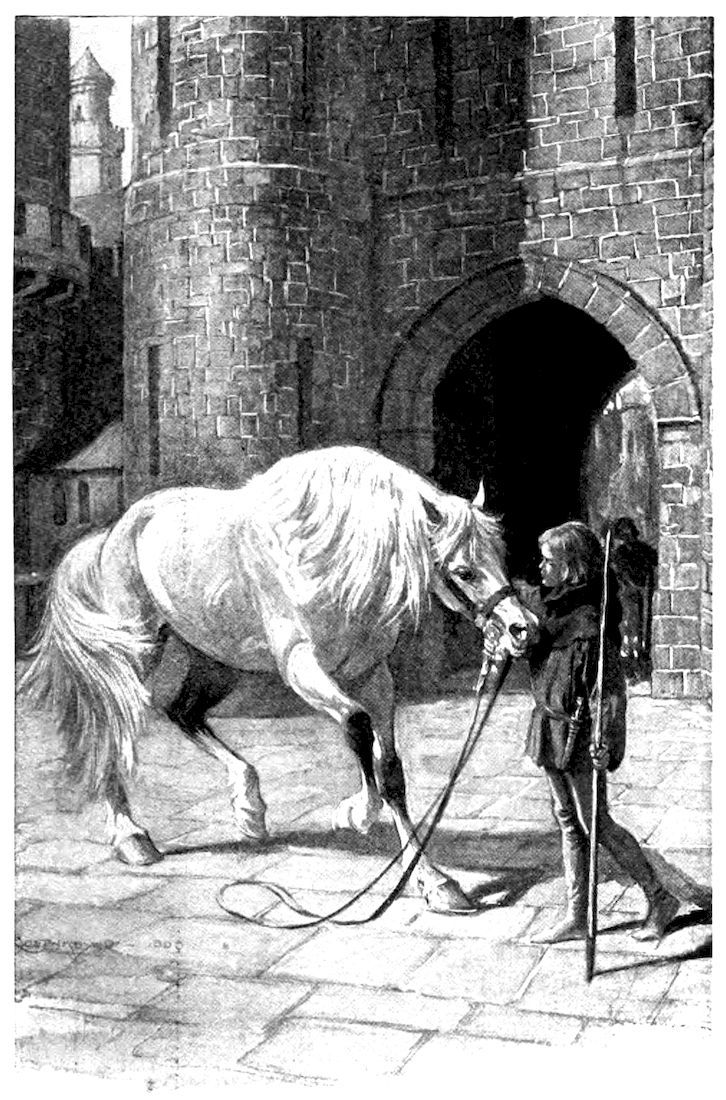

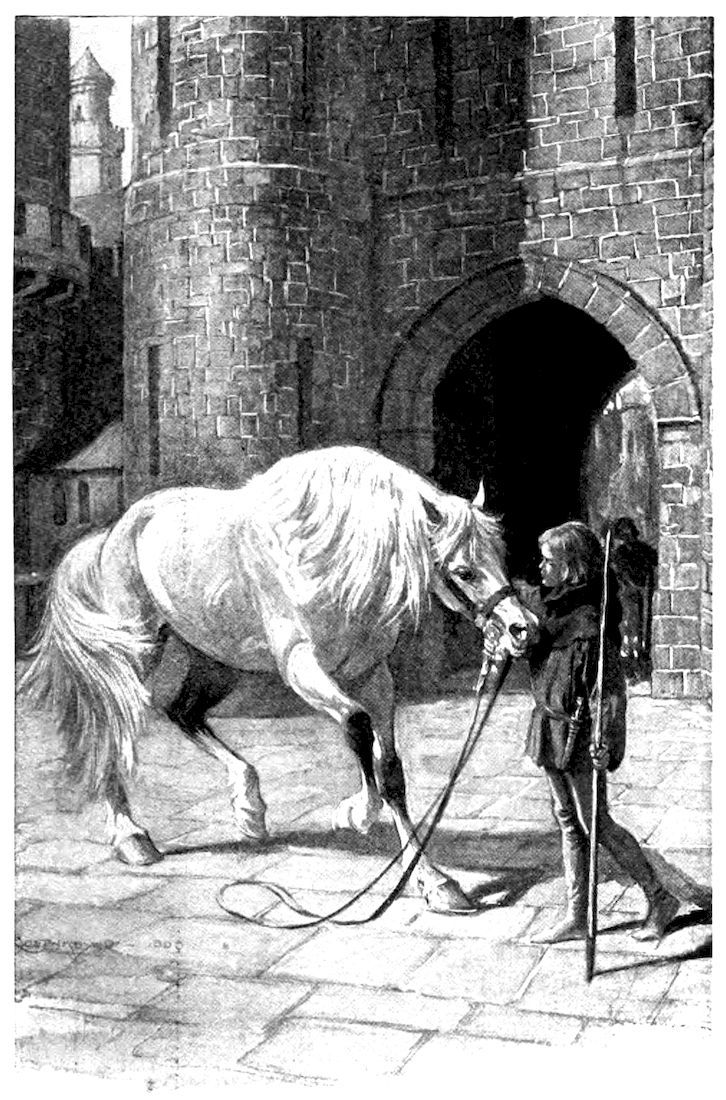

Then were all who looked on amazed at what they saw, for close beside Wulf the horse stopped and began smelling the boy. Then he took to trembling in all his legs, and arched his neck and thrust his big head against Wulf’s breast, until, half dazed, the boy raised a hand and began patting the broad neck and stroking the mane of the charger.

“By the rood,” cried one of the grooms, “the tinker hath the horseman’s word, and no mistake! The old imp knows it.”

“THE BOY BEGAN PATTING THE BROAD NECK OF THE CHARGER.”

“See if thou canst take the halter, boy,” called Herr Werner; and laying a hand upon the rein, Wulf stepped back a pace, whereupon the horse pressed close to him and whinnied eagerly, as if fearful that Wulf would leave him. He smelled him over again, thrusting his muzzle now into Wulf’s hands, now against his face, and putting up his nose to take the boy’s breath, as horses do with those they love.

“By my forefathers!” cried Herr Werner. “Could Herr Banf see him now—aha!”

He paused; for, hurrying into the courtyard, followed by still another frightened groom, came a knight who, seeing Wulf and the horse, stood as if rooted in his tracks. Softly now the charger stepped about the boy, nickering under his breath, so low that his nostrils hardly stirred; and at last he brought his knees to the pave, stooping meekly, as one who loved a service he would do, and thus waited.

An instant Wulf stood dazed. Then he passed his hand across his forehead; for a strange, troubled notion, as of some forgotten dream, passed through his brain. At last, obeying some impelling instinct, that yet seemed to him like a memory, he laid a hand upon the horse’s withers and sprang to his back.

Up, then, rose the noble creature, and stepped about the courtyard, tossing his head and gently champing the bit, as a horse will when he is pleased.

“Ride him to the stables, boy, and I will have word with thee there,” cried the older knight, who had come out last; and pressing the rein, though still wondering to himself how he knew what to do, Wulf turned the steed through the inner gate, to the bailey, and letting him have his head, was carried proudly to the stables, whence the throng of grooms and stable-boys had come rushing. They came to the group of outbuildings and offices that made up the stables, followed by all the men, Herr Banf in the lead, and the place, which had been quite deserted, was immediately thronged, attendants from the castle itself coming on a run, as news spread of the wonderful thing that was happening.

Once within the stable-yard, the horse stood quiet to let Wulf dismount; but not even Herr Banf himself would he let lay a hand upon him, though he stood meek as a sheep while the boy, instructed by the knight, did off the bridle and fastened on the halter; then he led his charge into a stall that one of the lads pointed out to him, and made him fast before the manger. When this was done the horse gave a rub of his head against Wulf, and then turned to eating his fodder, quietly, as though he never had done otherwise.

Then Herr Banf took to questioning Wulf sharply; but the boy could tell him but little. Indeed, some instinct warned him against speaking even of the faint thoughts stirring within him. He was full of anxiety to get away to Karl and tell him of this wonderful new experience, and he could say naught to the knight, save that he was Karl the armorer’s grandson, that he had never had the care of horses, and in his life had backed but few, chiefly those of the men-at-arms who rode with their masters to the forge when Karl’s skill was needed. He was troubled, too, about Karl’s hurt, of which he told Herr Banf, and begged to be let to hasten back to the smithy.

“Go, then,” said Herr Banf, at last, “and I will see thy grandsire to-morrow; thou’rt too promising a varlet to be left to grow up an armorer. We need thy kind elsewhere.”

So, when he had given the nearly forgotten corselet to Gotta Brent, Wulf fared down the rocky way to the forge, where he told Karl all that had chanced to him that day.

“Let that remain with thee alone, boy,” the armorer said, when the boy had told him of the strange memories that teemed in his brain. “These are no times to talk of such matters an thou ’dst keep a head on thy shoulders. Thou’rt of my own raising, Wulf; but more than that I cannot tell thee, for I do not know.” And there the lad was forced to let the matter rest.

“It is all one with my dreams,” he said to himself, as he sought his bed of skins. “Mayhap other dreams will make it clearer.”

But no dreams troubled his healthy boy’s sleep that night, nor woke he until the morning sun streamed full in his upturned face.