8

The year proved a rarely good one over all the north part of the Dale. The hay crop was heavy, and it was got in dry; the folk came home from the sæters in autumn with great store of dairy-stuff and full and fat flocks and herds—they had been mercifully spared from wild beasts, too, this year. The corn stood tall and thick as few folks could call to mind having seen it before—it grew full-eared and ripened well, and the weather was fair as heart could wish. Between St. Bartholomew’s and the Virgin’s Birthfeast, the time when night-frosts were most to be feared, it rained a little and was mild and cloudy, but thereafter the time of harvest went by with sun and wind and mild, misty nights. The week after Michaelmas most of the corn had been garnered all over the parish.

At Jörundgaard all folks were toiling and moiling, making ready for the great wedding. The last two months Kristin had been so busy from morning to night that she had but little time to trouble over aught but her work. She saw that her bosom had filled out; the small pink nipples were grown brown, and they were tender as smarting hurts when she had to get out of bed in the cold—but it passed over when she had worked herself warm, and after that she had no thought but of all she must get done before evening. When now and again she was forced to straighten up her back and stand and rest a little, she felt that the burden she bore was growing heavy—but to look on she was still slim and slender as she had ever been. She passed her hands down her long shapely thighs. No, she would not grieve over it now. Sometimes a faint creeping longing would come over her with the thought: like enough in a month or so she might feel the child quick within her—By that time she would be at Husaby.—Maybe Erlend would be glad—She shut her eyes and fixed her teeth on her betrothal ring—then she saw before her Erlend’s face, pale and moved, as he stood in the hall here in the winter and said the words of espousal with a loud clear voice:

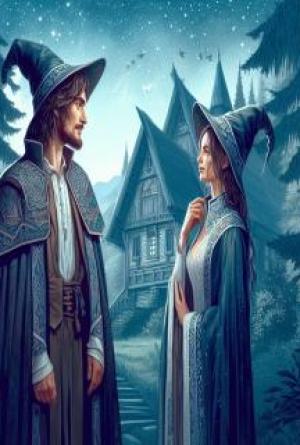

“So be God my witness and these men standing here, that I Erlend Nikulaussön do espouse Kristin Lavransdatter according to the laws of God and men, on such conditions as here have been spoken before these witnesses standing hereby. That I shall have thee to my wife and thou shalt have me to thy husband, so long as we two do live, to dwell together in wedlock, with all such fellowship as God’s law and the law of the land do appoint.”

As she ran on errands from house to house across the farm-place, she stayed a moment—the rowan trees were so thick with berries this year—’twould be a snowy winter. The sun shone over the pale stubble fields where the corn sheaves stood piled on their stakes. If this weather might only hold over the wedding!

Lavrans stood firmly to it that his daughter should be wedded in church. It was fixed, therefore, that the wedding should be in the chapel at Sundbu. On the Saturday the bridal train was to ride over the hills to Vaage; they were to lie for the night at Sundbu and the neighbouring farms, and ride back on Sunday after the wedding-mass. The same evening after Vespers, when the holy day was ended, the wedding feast was to be held, and Lavrans was to give his daughter away to Erlend. And after midnight the bride and bridegroom were to be put to bed.

On Friday, after noon, Kristin stood in the upper hall balcony, watching the bridal train come riding from the north, past the charred ruins of the church on the hillside. It was Erlend coming with all his groomsmen; she strained her eyes to pick him out among the others. They must not see each other—no man must see her now before she was led forth to-morrow in her bridal dress.

Where the ways divided, a few women left the throng and took the road to Jörundgaard. The men rode on toward Laugarbru; they were to sleep there that night.

Kristin went down to meet the comers. She felt wearied after the bath, and the skin of her head was sore from the strong lye her mother had used to wash her hair, that it might shine fair and bright on the morrow.

Lady Aashild slipped down from her saddle into Lavrans’ arms. How can she keep so light and young, thought Kristin. Her son Sir Munan’s wife, Lady Katrin, might have passed for older than she; a big plump dame, with dull and hueless skin and eyes. Strange, thought Kristin; she is ill-favoured and he is unfaithful, and yet folks say they live well and kindly together. Then there were two daughters of Sir Baard Petersön, one married and one unmarried. They were neither comely nor ill-favoured; they looked honest and kind, but held themselves something stiffly in the strange company. Lavrans thanked them courteously that they had been pleased to honour this wedding at the cost of so far a journey so late in the year.

“Erlend was bred in our father’s house, when he was a boy,” said the elder, moving forward to greet Kristin.

But now two youths came riding into the farm-place at a sharp trot—they leaped from their horses and rushed laughing after Kristin, who ran indoors and hid herself. They were Trond Gjesling’s two young sons, fair and likely lads. They had brought the bridal crown with them from Sundbu in a casket. Trond and his wife were not to come till Sunday, when they would join the bridal train after the mass.

Kristin fled into the hearth-room; and Lady Aashild, coming after, laid her hands on the girl’s shoulders, and drew down her face to hers to kiss it.

“Glad am I that I live to see this day,” said Lady Aashild.

She saw how thin they were grown, Kristin’s hands, that she held in hers. She saw that all else about her was grown thin, but that her bosom was high and full. All the features of the face were grown smaller and finer than before; the temples seemed as though sunken in the shadow of the heavy, damp hair. The girl’s cheeks were round no longer, and her fresh hue was faded. But her eyes were grown much larger and darker.

Lady Aashild kissed her again:

“I see well you have had much to strive against, Kristin,” she said. “To-night will I give you a sleepy drink, that you may be rested and fresh to-morrow.”

Kristin’s lips began to quiver.

“Hush,” said Lady Aashild, patting her hand. “I joy already that I shall deck you out to-morrow—none hath seen a fairer bride, I trow, than you shall be to-morrow.”

Lavrans rode over to Laugarbru to feast with his guests who were housed there.

The men could not praise the food enough—better Friday food than this a man could scarce find in the richest monastery. There was rye-meal porridge, boiled beans and white bread—for fish they had only trout, salted and fresh, and fat dried halibut.

As time went on and the men drank deeper, they grew ever more wanton of mood, and the jests broken on the bridegroom’s head ever more gross. All Erlend’s groomsmen were much younger than he—his equals in age and his friends were all long since wedded men. The darling jest among the groomsmen now was that he was so aged a man and yet was to mount the bridal bed for the first time. Some of Erlend’s older kinsmen, who yet kept their wits, sat in dread, at each new sally, that the talk would come in upon matters it were best not to touch. Sir Baard of Hestnæs kept an eye on Lavrans. The host drank deep, but it seemed not that the ale made him more joyful—he sat in the high-seat, his face growing more and more strained, even as his eyes grew more fixed. But Erlend, who sat on his father-in-law’s right hand, answered in kind the wanton jests flung at him, and laughed much; his face was flushed red and his eyes sparkled.

Of a sudden Lavrans flew out:

“That cart, son-in-law—while I remember—what have you done with the cart you had of me on loan in the summer?”

“Cart—?” said Erlend.

“Have you forgot already that you had a cart on loan from me in the summer—God knows ’twas so good a cart I look not ever to see a better, for I saw to it myself when ’twas making in my own smithy on the farm. You promised and you swore—I take God to witness, and my house-folk know it besides—you gave your word to bring it back to me—but that word you have not kept—”

Some of the guests called out that this was no matter to talk of now, but Lavrans smote the board with his fist and swore that he would know what Erlend had done with his cart.

“Oh like enough it lies still at the farm at Næs, where we took boat out to Veöy,” said Erlend lightly. “I thought not ’twas meant so nicely. See you, father-in-law, thus it was—’twas a long and toilsome journey with a heavy-laden cart over the hills, and when we were come down to the fjord, none of my men had a mind to bring the cart all the way back here, and then journey north again over the hills to Trondheim. So we thought we might let it be there for a time—”

“Now, may the devil fly off with me from where I sit this very hour, if I have ever heard of your like,” Lavrans burst out. “Is this how things are ordered in your house—doth the word lie with you or with your men, where they are to go or not to go—?”

Erlend shrugged his shoulders:

“True it is, much hath been as it should not have been in my household—But now will I have the cart sent south to you again, when Kristin and I are come thither—Dear my father-in-law,” said he, smiling and holding out his hand, “be assured, ’twill be changed times with all things, and with me too, when once I have brought Kristin home to be mistress of my house. ’Twas an ill thing, this of the cart. But I promise you, this shall be the last time you have cause of grief against me.”

“Dear Lavrans,” said Baard Petersön, “forgive him in this small matter—”

“Small matter or great—” began Lavrans—but checked himself, and took Erlend’s hand.

Soon after he made the sign for the feast to break up, and the guests sought their sleeping-places.

On the Saturday before noon all the women and girls were busy in the old store-house loft-room, some making ready the bridal bed, some dressing and adorning the bride.

Ragnfrid had chosen this house for the bride-house, in part for its having the smallest loft-room—they could make room for many more guests in the new store-house loft, the one they had used themselves in summer time to sleep in when Kristin was a little child, before Lavrans had set up the great new dwelling-house, where they lived now both summer and winter. But besides this, there was no fairer house on the farm than the old store-house, since Lavrans had had it mended and set in order—it had been nigh falling to the ground when they moved in to Jörundgaard. It was adorned with the finest woodcarving both outside and in, and if the loft-room were not great, ’twas the easier to hang it richly with rugs and tapestries and skins.

The bridal bed stood ready made, with silk-covered pillows; fine hangings made as it were a tent about it; over the skins and rugs on the bed was spread a broidered silken coverlid. Ragnfrid and some other women were busy now hanging tapestries on the timber walls and laying cushions in order on the benches.

Kristin sat in a great arm-chair that had been brought up thither. She was clad in her scarlet bridal robe. Great silver brooches held it together over her bosom, and fastened the yellow silk shift showing in the neck-opening; golden armlets glittered on the yellow silken sleeves. A silver-gilt belt was passed thrice around her waist, and on her neck and bosom lay neck-chain over neck-chain, the uppermost her father’s old gold chain with the great reliquary cross. Her hands, lying in her lap, were heavy with rings.

Lady Aashild stood behind her chair, brushing her heavy, gold-brown hair out to all sides.

“To-morrow shall you spread it loose for the last time,” she said smiling, as she wound the red and green silk cords that were to hold up the crown, around Kristin’s head—Then the women came thronging round the bride.

Ragnfrid and Gyrid of Skog took the great bridal crown of the Gjesling kin from the board. It was gilt all over, the points ended in alternate crosses and clover-leaves, and the circlet was set with great rock-crystals.

They pressed it down on the bride’s head. Ragnfrid was pale, and her hands were shaking, as she did it.

Kristin rose slowly to her feet. Jesus! how heavy ’twas to bear up all this gold and silver—Then Lady Aashild took her by the hand and led her forward to a great tub of water—while the bridesmaids flung open the door to the outer sunlight, so that the light in the room should be bright.

“Look now at yourself in the water, Kristin,” said Lady Aashild, and Kristin bent over the tub. She caught a glimpse of her own face rising up white through the water; it came so near that she saw the golden crown above it. Round about, many shadows, bright and dark, were stirring in the mirror—there was somewhat she was on the brink of remembering—then ’twas as though she was swooning away—she caught at the rim of the tub before her. At that moment Lady Aashild laid her hand on hers, and drove her nails so hard into the flesh, that Kristin came to herself with the pain.

Blasts of a great horn were heard from down by the bridge. Folk shouted up from the courtyard that the bridegroom was coming with his train. The women led Kristin out onto the balcony.

In the courtyard was a tossing mass of horses in state trappings and people in festival apparel, all shining and glittering in the sun. Kristin looked out beyond it all, far out into the Dale. The valley of her home lay bright and still beneath a thin misty-blue haze; up above the haze rose the mountains, grey with screes and black with forest, and the sun poured down its light into the great bowl of the valley from a cloudless sky.

She had not marked it before, but the trees had shed all their leaves—the groves around shone naked and silver-grey. Only the alder thickets along the river had a little faded green on their topmost branches, and here and there a birch had a few yellow-white leaves clinging to its outermost twigs. But, for the most the trees were almost bare—all but the rowans; they were still bright, with red-brown leaves around the clusters of their blood-red berries. In the still, warm day a faint mouldering smell of autumn rose from the ashen covering of fallen leaves that strewed the ground all about.

Had it not been for the rowans, it might have been early spring. And the stillness too—but this was an autumn stillness, deathly still. When the horn-blasts died away, no other sound was heard in all the valley but the tinkling of bells from the stubble fields and fallows where the beasts wandered, grazing.

The river was shrunken small, its roar sunk to a murmur; it was but a few strands of water running amidst banks of sand and great stretches of white round boulders. No noise of becks from the hillsides—the autumn had been so dry. The fields all around still gleamed wet—but ’twas but the wetness that oozes up from the earth in autumn, howsoever warm the days may be, and however clear the air.

The crowd that filled the farm-place fell apart to make way for the bridegroom’s train. Straightway the young groomsmen came riding forward—there went a stir among the women in the balcony.

Lady Aashild was standing by the bride:

“Bear you well now, Kristin,” said she, “’twill not be long now till you are safe under the linen coif.”

Kristin nodded helplessly. She felt how deathly white her face must be.

“Methinks I am all too pale a bride,” she said in a low voice.

“You are the fairest bride,” said Lady Aashild; “and there comes Erlend, riding—fairer pair than you twain would be far to seek.”

Now Erlend himself rode forward under the balcony. He sprang lightly from his horse, unhindered by his heavy, flowing garments. He seemed to Kristin so fair that ’twas pain to look on him.

He was in dark raiment, clad in a slashed silken coat falling to the feet, leaf-brown of hue and inwoven with black and white. About his waist he had a gold-bossed belt, and at his left thigh hung a sword with gold on hilt and sheath. Back over his shoulders fell a heavy dark-blue velvet cloak, and pressed down on his coal-black hair he wore a black French cap of silk that stood out at both sides in puckered wings, and ended in two long streamers, whereof one was thrown from his left shoulder right across his breast and out behind over the other arm.

Erlend bowed low before his bride as she stood above; then went up to her horse and stood by it with his hand on the saddle-bow, while Lavrans went up the stairs. A strange dizzy feeling came over Kristin at the sight of all this splendour—in this solemn garment of green velvet, falling to his feet, her father might have been some stranger. And her mother’s face, under the linen coif, showed ashen-grey against the red of her silken dress. Ragnfrid came forward and laid the cloak about her daughter’s shoulders.

Then Lavrans took the bride’s hand and led her down to Erlend. The bridegroom lifted her to the saddle, and himself mounted. They stayed their horses, side by side, these two, beneath the bridal balcony, while the train began to form and ride out through the courtyard gate. First the priests: Sira Eirik, Sira Tormod from Ulvsvolden, and a Brother of the Holy Cross from Hamar, a friend of Lavrans. Then came the groomsmen and the bridesmaids, pair by pair. And now ’twas for Erlend and her to ride forth. After them came the bride’s parents, the kinsmen, friends and guests, in a long line down betwixt the fences to the highway. Their road for a long way onward was strewn with clusters of rowan-berries, branches of pine, and the last white dogfennel of autumn, and folk stood thick along the waysides where the train passed by, greeting them with a great shouting.

On the Sunday, just after sunset, the bridal train rode back to Jörundgaard. Through the first falling folds of darkness the bonfires shone out red from the courtyard of the bridal-house. Minstrels and fiddlers were singing and making drums and fiddles speak as the crowd of riders drew near to the warm red glare of the fires.

Kristin came near to falling her length on the ground when Erlend lifted her from her horse beneath the balcony of the upper hall.

“Twas so cold upon the hills,” she whispered—“I am so weary—” She stood for a moment—and when she climbed the stairs to the loft-room she swayed and tottered at each step.

Up in the hall the half-frozen wedding-guests were soon warmed up again. The many candles burning in the room gave out heat; smoking hot dishes of food were borne around, and wine, mead and strong ale circled about. The loud hum of voices, and the noise of many eating sounded like a far off roaring in Kristin’s ears.

It seemed as she sat there she would never be warm through again. In a while her cheeks began to burn, but her feet were still unthawed, and shudders of cold ran down her back. All the heavy gold that was on her head and body forced her to lean forward as she sat in the high-seat by Erlend’s side.

Every time her bridegroom drank to her, she could not keep her eyes from the red stains and patches that stood out on his face so sharply as he began to grow warm after his ride in the cold. They were the marks left by the burns of last summer.

The horror had come upon her last evening, when they sat over the supper-board at Sundbu, and she met Björn Gunnarsön’s lightless eyes fixed on her and Erlend—unwinking, unwavering eyes. They had dressed up Sir Björn in knightly raiment—he looked like a dead man brought to life by an evil spell.

At night she had lain with Lady Aashild—the bridegroom’s nearest kinswoman in the wedding company.

“What is amiss with you, Kristin?” said Lady Aashild, a little sharply. “Now is the time for you to bear up stiffly to the end—not give way thus.”

“I am thinking,” said Kristin, cold with dread, “on all them we have brought to sorrow, that we might see this day.”

“’Tis not joy alone, I trow, that you two have had,” said Lady Aashild. “Not Erlend at the least. And methinks it has been worse still for you.”

“I am thinking on his helpless children,” said the bride again. “I am wondering if they know their father is drinking to-day at his wedding feast.—”

“Think on your own child,” said the Lady. “Be glad that you are drinking at your wedding with him who is its father.”

Kristin lay awhile, weak and giddy. ’Twas so strange to hear that name, that had filled her heart and mind each day for three months and more, and whereof yet she had not dared speak a word to a living soul. It was but for a little though, that this helped her.

“I am thinking of her who had to pay with her life, because she held Erlend dear,” she whispered, shivering.

“Well if you come not to pay with your life yourself, ere you are half a year older,” said Lady Aashild harshly. “Be glad while you may—

“What shall I say to you, Kristin?” said the old woman in a while, despairingly. “Have you clean lost courage this day of all days? Soon enough will it be required of you twain that you shall pay for all you have done amiss—have no fear that it will not be so.”

But Kristin felt as though all things in her soul were slipping, slipping—as though all were toppling down that she had built up since that day of horror at Haugen, in that first time when, wild and blind with fear, she had thought but of holding out one day more, and one day more. And she had held out till her load grew lighter—and at last grew even light, when she had thrown off all thought but this one thought: that now their wedding-day was coming at last, Erlend’s wedding-day at last.

But, when she and Erlend knelt together in the wedding-mass, all around her seemed but some trickery of the sight—the tapers, the pictures, the glittering vessels, the priests in their copes and white gowns. All those who had known her where she had lived before—they seemed like visions of a dream, standing there, close-packed in the church in their unwonted garments. But Sir Björn stood against a pillar, looking at those two with his dead eyes, and it seemed to her that that other who was dead must needs have come back with him, on his arm.

She tried to look up at Saint Olav’s picture—he stood there red and white and comely, leaning on his axe, treading his own sinful human nature underfoot—but her glance would ever go back to Sir Björn; and nigh to him she saw Eline Ormsdatter’s dead face, looking unmoved upon her and Erlend. They had trampled her underfoot that they might come hither—and she grudged it not to them.

The dead woman had arisen and flung off her all the great stones that Kristin had striven to heap up above her. Erlend’s wasted youth, his honour and his welfare, his friends’ good graces, his soul’s health. The dead woman had shaken herself free from them all. “He would have me and I would have him; you would have him and he would have you,” said Eline. “I have paid—and he must pay and you must pay when your time comes. When the time of sin is fulfilled, it brings forth death—”

It seemed to her she was kneeling with Erlend on a cold stone. He knelt there with the red, burnt patches on his pale face; she knelt under the heavy bridal crown, and felt the dull, crushing weight within her—the burden of sin that she bore. She had played and wantoned with her sin, had measured it as in a childish game. Holy Virgin—now the time was nigh when it should lie full-born before her, look at her with living eyes; show her on itself the brands of sin, the hideous deformity of sin; strike in hate with misshapen hands at its mother’s breast. When she had borne her child, when she saw the marks of her sin upon it and yet loved it as she had loved her sin, then would the game be played to an end.

Kristin thought what if she shrieked aloud now, a shriek that would cut through the song and the deep voices intoning the mass, and echo out over the people’s heads? Would she be rid then of Eline’s face—would there come life into the dead man’s eyes? But she clenched her teeth together.

“—Holy King Olav, I cry upon thee. Above all in Heaven I pray for help to thee, for I know thou didst love God’s justice above all things. I call upon thee, that thou hold thy hand over the innocent that is in my womb. Turn away God’s wrath from the innocent; turn it upon me; Amen, in the precious name of the Lord—”

“My children,” said Eline’s voice, “are they not guiltless? Yet is there no place for them in the lands where Christians dwell. Your child is begotten outside the law, even as were my children. No rights can you claim for it in the land you have strayed away from, any more than I for mine—”

“Holy Olav! Yet do I pray for grace. Pray thou for mercy for my son; take him beneath thy guard; so shall I bear him to thy church on my naked feet, so shall I bear my golden garland of maidenhood in to thee and lay it down upon thy altar, if thou wilt but help me—amen.”

Her face was set hard as stone in her struggle to be still and calm; but her whole body throbbed and quivered as she knelt there through the holy mass that wedded her to Erlend.

And now, as she sat beside him in the high-seat at home, all things around her were but as shadows in a fevered dream.

There were minstrels playing on harps and fiddles in the loft-room; and the sound of music and song rose from the hall below and the courtyard outside. There was a red glare of fire from without, when the door was opened for the dishes and tankards to be borne in and out.

Those around the board were standing now; she was standing up between her father and Erlend. Her father made known with a loud voice that he had given Erlend Nikulaussön his daughter Kristin to wife. Erlend thanked his father-in-law, and he thanked all good folk who had come together there to honour him and his wife.

She was to sit down, they said—and now Erlend laid his bridal gifts in her lap. Sira Eirik and Sir Munan Baardsön unrolled deeds and read aloud from them concerning the jointures and settlements of the wedded pair; while the groomsmen stood around, with spears in their hands, and now and again during the reading, or when gifts and bags of money were laid on the table, smote with the butts upon the floor.

The tables were cleared away; Erlend led her forth upon the floor, and they danced together. Kristin thought: our groomsmen and our bridesmaids—they are all too young for us—all they that were young with us are gone from these places; how is it we are come back hither?

“You are so strange, Kristin,” whispered Erlend, as they danced. “I am afraid of you, Kristin—are you not happy—?”

They went from house to house and greeted their guests. There were many lights in all the rooms, and everywhere crowds of people drinking and singing and dancing. It seemed to Kristin she scarce knew her home again—and she had lost all knowledge of time—hours and the pictures of her brain seemed strangely to float about loosely, mingled with each other.

The autumn night was mild; there were minstrels in the courtyard too, and people dancing round the bonfire. They cried out that the bride and bridegroom must honour them, too—and then she was dancing with Erlend on the cold, dewy sward. She seemed to wake a little then, and her head grew more clear.

Far out in the darkness a band of white mist floated above the murmur of the river. The mountains stood around coal-black against the star-sprinkled sky.

Erlend led her out of the ring of dancers—and crushed her to him in the darkness under the balcony.

“Not once have I had the chance to tell you—you are so fair—so fair and so sweet. Your cheeks are red as flames—” he pressed his cheek to hers as he spoke. “Kristin, what is it ails you—?”

“I am so weary, so weary,” she whispered back.

“Soon will we go and sleep,” answered her bridegroom, looking up at the sky. The Milky Way had wheeled, and now lay all but north and south. “Mind you that we have not once slept together since that one only night I was with you in your bower at Skog?”

Soon after, Sira Eirik shouted with a loud voice out over the farmstead that now it was Monday. The women came to lead the bride to bed. Kristin was so weary that she was scarce able to struggle and hold back as ’twas fit and seemly she should do. She let herself be seized and led out of the loft-room by Lady Aashild and Gyrid of Skog. The groomsmen stood at the foot of the stair with burning torches and naked swords; they formed a ring round the troop of women and attended Kristin across the farm-place, and up into the old loft-room.

The women took off her bridal finery, piece by piece, and laid it away. Kristin saw that over the bed-foot hung the violet velvet robe she was to wear on the morrow, and upon it lay a long, snow-white, finely-pleated linen cloth. It was the wife’s linen coif. Erlend had brought it for her; to-morrow she was to bind up her hair in a knot and fasten the head-linen over it. It looked to her so fresh and cool and restful.

At last she was standing before the bridal bed, on her naked feet, bare-armed, clad only in the long golden-yellow silken shift. They had set the crown on her head again—the bridegroom was to take it off, when they two were left alone.

Ragnfrid laid her hands on her daughter’s shoulders, and kissed her on the cheek—the mother’s face and hands were strangely cold, but it was as though sobs were struggling, deep in her breast. Then she threw back the coverings of the bed, and bade the bride seat herself in it. Kristin obeyed, and leaned back on the pillows heaped up against the bed-head—she had to bend her head a little forward to keep on the crown. Lady Aashild drew the coverings up to the bride’s waist, and laid her hands before her on the silken coverlid; then took her shining hair and drew it forward over her bosom and the slender bare upper arms.

Next the men led the bridegroom into the loft-room. Munan Baardsön unclasped the golden belt and sword from Erlend’s waist—when he leaned over to hang it on the wall above the bed, he whispered something to the bride—Kristin knew not what he said, but she did her best to smile.

The groomsmen unlaced Erlend’s silken robe and lifted off the long heavy garment over his head. He sat him down in the great chair and they helped him off with his spurs and boots—

Once and once only the bride found courage to look up and meet his eyes—

Then began the good-nights. Before long all the wedding-guests were gone from the loft. Last of all, Lavrans Björgulfsön went out and shut the door of the bride-house.

Erlend stood up, stripped off his under-clothing, and flung it on the benches. He stood by the bed, took the crown and the silken cords from off her hair, and laid them away on the table. Then he came back and mounted into the bed. Kneeling by her side he clasped her round the head, and pressed it in against his hot naked breast, while he kissed her forehead all along the red-streak the crown had left on it.

She threw her arms about his shoulders and sobbed aloud—she had a sweet, wild feeling that now the horror, the phantom visions were fading into air—now, now once again naught was left but he and she. He lifted up her face a moment, looked down into it, and drew his hand down over her face and body, with a strange haste and roughness, as though he tore away a covering:

“Forget,” he begged, in a fiery whisper, “forget all, my Kristin—all but this, that you are my own wife, and I am your own husband—”

With his hand he quenched the flame of the last candle, then threw himself down beside her in the dark—he too was sobbing now:

“Never have I believed it, never in all these years, that we should see this day—”

Without, in the courtyard, the noise died down little by little. Wearied with the long day’s ride, and dizzy with much strong drink, the guests made a decent show of merry-making a little while yet—but more and ever more of them stole away and sought out the places where they were to sleep.

Ragnfrid showed all the guests of honour to their places, and bade them good-night. Her husband, who should have helped her in this, was nowhere to be seen.

The dark courtyard was empty, save for a few small groups of young folks—servants most of them—when at last she stole out to find her husband and bring him with her to his bed. She had seen as the night wore on that he had grown very drunken.

She stumbled over him at last, as she crept along in her search outside the cattle-yard—he was lying in the grass behind the bath-house, on his face.

Groping in the darkness, she touched him with her hand—aye, it was he. She thought he was asleep, and took him by the shoulder—she must get him up off the icy-cold ground. But he was not asleep, at least, not wholly.

“What would you?” he asked, in a thick voice.

“You cannot lie here,” said his wife. She held him up, as he stood swaying. With one hand she brushed the soil off his velvet robe. “’Tis time we too went to rest, husband.” She took him by the arm, and drew him, reeling, up towards the farm-yard buildings.

“You looked not up, Ragnfrid, when you sat in the bridal bed beneath the crown,” he said in the same voice. “Our daughter—she was not so shamefast—her eyes were not shamefast when she looked upon her bridegroom.”

“She has waited for him seven half-years,” said the mother in a low voice. “No marvel if she found courage to look up—”

“Nay, devil damn me if they have waited!” screamed the man—as his wife strove fearfully to hush him.

They were in the narrow passage between the back of the privy and a fence. Lavrans smote with his clenched fist on the beam across the cess-pit:

“I set thee here for a scorn and for a mockery, thou beam. I set thee here that filth might eat thee up. I set thee here in punishment for striking down that tender little maid of mine.—I should have set thee high above my hall-room door; and honoured thee and thanked thee with fairest carven ornament; because thou didst save her from shame and from sorrow,—because ’twas thy work that my Ulvhild died a sinless child—”

He turned about, reeled toward the fence and fell forward upon it, and with his head between his arms fell into an unquenchable passion of weeping, broken by long, deep groans.

His wife took him by the shoulder.

“Lavrans, Lavrans!” But she could not stay his weeping. “Husband.”

“Oh, never, never, never should I have given her to that man! God help me—I must have known it all the time—he had broken down her youth and her fairest honour. I believed it not—nay, could I believe the like of Kristin?—but still I knew it. And yet is she too good for this weakling boy, that hath made waste of himself and her—had he lured her astray ten times over, I should never have given her to him, that he may spill yet more of her life and her happiness—”

“But what other way was there?” said the mother despairingly. “You know now, as well as I—she was his already—”

“Aye, small need was there for me to make such a mighty to-do in giving Erlend what he had taken for himself already,” said Lavrans. “’Tis a gallant husband she has won—my Kristin—” He tore at the fence; then fell again a-weeping. He had seemed to Ragnfrid as though sobered a little, but now the fit overcame him again.

She deemed she could not bring him, drunken and beside himself with despair as he was, to the bed in the hearth-room where they should have slept—for the room was full of guests. She looked about her—close by stood a little barn where they kept the best hay to feed to the horses at the spring ploughing. She went and peered in—no one was there; she took her husband’s hand, led him inside the barn, and shut the door behind them.

She piled up hay over herself and him and laid their cloaks above it to keep them warm. Lavrans fell a-weeping now and again, and said somewhat—but his speech was so broken, she could find no meaning in it. In a little while she lifted up his head on to her lap.

“Dear my husband—since now so great a love is between them, maybe ’twill all go better than we think—”

Lavrans spoke by fits and starts—his mind seemed growing clearer:

“See you not—he has her wholly in his power—he that has never been man enough to rule himself.—’Twill go hard with her before she finds courage to set herself against aught her husband wills—and should she one day be forced to it, ’twill be bitter grief to her—my own gentle child—

—“Now am I come so far I scarce can understand why God hath laid so many and such heavy sorrows upon me—for I have striven faithfully to do His will. Why hath He taken our children from us, Ragnfrid, one by one—first our sons—then little Ulvhild—and now I have given her that I loved dearest, honourless, to an untrusty and a witless man. Now is there none left to us but the little one—and unwise must I deem it to take joy in her, before I see how it will go with her—with Ramborg.”

Ragnfrid shook like a leaf. Then the man laid his arm about her shoulders:

“Lie down,” he said, “and let us sleep—” He lay for a while with his head against his wife’s arm, sighing now and then, but at last he fell asleep.

It was still pitch-dark in the barn when Ragnfrid stirred—she wondered to find that she had slept. She felt about with her hands; Lavrans was sitting up with knees updrawn and his arms around them.

“Are you awake already?” she asked in wonder. “Are you cold?”

“No,” said he in a hoarse voice, “but I cannot go to sleep again.”

“Is it Kristin you are thinking on?” asked the mother. “Like enough ’twill go better than we think, Lavrans,” she said again.

“Aye, ’tis of that I was thinking,” said the man. “Aye, aye—maid or woman, at least she is come to the bride-bed with the man she loves. And ’twas not so with either you or me, my poor Ragnfrid.”

His wife gave a deep, dull moan, and threw herself down on her side amongst the hay. Lavrans put out a hand and laid it on her shoulder.

“But ’twas that I could not,” said he, with passion and pain. “No, I could not—be as you would have had me—when we were young. I am not such a one—”

In a while Ragnfrid said softly through her weeping:

“Yet ’twas well with us in our life together—Lavrans—was it not?—all these years?”

“So thought I myself,” answered he gloomily.

Thoughts crowded and tossed to and fro within him. That single unveiled glance in which the hearts of bridegroom and bride had leapt together—the two young faces flushing up redly—to him it seemed a very shamelessness. It had been agony, a scorching pain to him, that this was his daughter. But the sight of those eyes would not leave him—and wildly and blindly he strove against the tearing away of the veil from something in his own heart, something that he had never owned was there, that he had guarded against his own wife when she sought for it.

’Twas that he could not, he said again stubbornly to himself. In the devil’s name—he had been married off as a boy; he had not chosen for himself; she was older than he—he had not desired her; he had had no will to learn this of her—to love. He grew hot with shame even now when he thought of it—that she would have had him love her, when he had no will to have such love from her. That she had proffered him all this that he had never prayed for.

He had been a good husband to her—so he had ever thought. He had shown her all the honour he could, given her full power in her own affairs, and asked her counsel in all things; he had been true to her—and they had had six children together. All he had asked had been that he might live with her, without her for ever grasping at this thing in his heart that he would not lay bare—

To none had he ever borne love—Ingunn, Karl Steinsön’s wife, at Bru? Lavrans flushed red in the pitch darkness. He had been their guest ever, as often as he journeyed down the Dale. He could not call to mind that he had spoken with the housewife once alone. But when he saw her—if he but thought of her, a sense came over him as of the first breath of the plough-lands in the spring, when the snows are but now melted and gone. He knew it now—it might have befallen him too—he, too, could have loved.

But he had been wedded so young, and he had grown shy of love. And so had it come about that he throve best in the wild woods—or out on the waste uplands—where all things that live must have wide spaces around them—room to flee through—fearfully they look on any stranger that would steal upon them—

One time in the year there was, when all the beasts in the woods and on the mountains forgot their shyness—when they rushed to their mates. But his had been given him unsought. And she had proffered him all he had not wooed her for.

But the young ones in the nest—they had been the little warm green spot in the wilderness—the inmost, sweetest joy of his life. Those little girl-heads under his hand—

Marriage—they had wedded him, almost unasked. Friends—he had many, and he had none. War—it had brought him gladness, but there had been no more war—his armour hung there in the loft-room, little used. He had turned farmer—But he had had his daughters—all his living and striving had grown dear to him, because by it he cherished them and made them safe, those soft, tender little beings he had held in his hands. He remembered Kristin’s little two-year-old body on his shoulder, her flaxen, silky hair against his cheek; her small hands holding to his belt, while she butted her round, hard child’s forehead against his shoulder-blades, when he rode out with her behind him on his horse.

And now had she that same glow in her eyes—and she had won what was hers. She sat there in the half-shadow against the silken pillows of the bed. In the candle-light she was all golden—golden crown and golden shift and golden hair spread over the naked golden arms. Her eyes were shy no longer—

Her father winced with shame.

And yet it was as though his heart was bleeding within him, for what he himself had never won; and for his wife, there by his side, whom he had never given what should have been hers.

Weak with pity, he felt in the darkness for Ragnfrid’s hand:

“Aye, methought it was well with us in our life together,” he said. “Methought ’twas but that you sorrowed for our children—aye, and that you were born heavy of mood. Never did it come to my mind, it might be that I was no good husband to you—”

Ragnfrid trembled fitfully:

“You were ever a good husband, Lavrans.”

“Hm,” Lavrans sat with his chin resting on his knees. “Yet had it mayhap been better with you, if you had been wedded even as our daughter was to-day—”

Ragnfrid started up with a low, piercing cry:

“You know! How did you know it—how long have you known—?”

“I know not what ’tis you speak of,” said Lavrans after a while in a strange deadened voice.

“This do I speak of—that I was no maid, when I came to be your wife,” said Ragnfrid, and her voice rang clear in her despair.

In a little while Lavrans answered, as before:

“That have I never known, till now.”

Ragnfrid laid her down among the hay, shaken with weeping. When the fit was over she lifted her head a little. A faint grey light was beginning to creep in through the window-hole in the wall. She could dimly see her husband sitting with his arms thrown round his knees, motionless as stone.

“Lavrans—speak to me—” she wailed.

“What would you I should say?” asked he without stirring.

“Oh—I know not—curse me—strike me—”

“’Twould be something late now,” answered the man; there seemed to be the shade of a scornful smile in his voice.

Ragnfrid wept again: “Aye—I heeded not then that I was betraying you. So betrayed and so dishonoured, methought, had I been myself. There was none had spared me. They came and brought you—you know yourself, I saw you but three times before we were wed—Methought you were but a boy, white and red—so young and childish—”

“I was so,” said Lavrans, and a faint ring of life came to his voice. “And therefore a man might deem that you, who were a woman—you might have been more afraid to—to deceive one who was so young that he knew naught—”

“So did I think after,” said Ragnfrid, weeping. “When I had come to know you. Soon came the time, when I would have given my soul twenty times over, to be guiltless of sin against you.”

Lavrans sat silent and motionless; then said his wife:

“You ask not anything?”

“What use to ask? It was he that—we met his burial-train at Feginsbrekka, as we bore Ulvhild in to Nidaros—”

“Aye,” said Ragnfrid. “We had to leave the way—go aside into a meadow. I saw them bear him on his bier—with priests and monks and armed yeomen. I heard he had made a good end—had made his peace with God. I prayed as we stood there with Ulvhild’s litter between us—I prayed that my sin and my sorrow might be laid at his feet on the Last Day—”

“Aye, like enough you did,” said Lavrans, and there was the same shade of scorn in his quiet voice.

“You know not all,” said Ragnfrid, cold with despair. “Mind you that he came out to us at Skog the first winter we were wedded—?”

“Aye,” answered the man.

“When Björgulf was born—oh, I thought he was dearer spared me—He was drunk when he did it—afterward he said he had never cared for me, he would not have me—bade me forget it. My father knew it not; he did not betray you—never think that. But Trond—we were the dearest of friends to each other then—I made my moan to him. He tried to force the man to wed me; but he was but a boy; he was beaten—Afterwards he counselled me to hold my peace, and to take you—”

She sat a while in silence.

“Then he came out to Skog—a year was gone by; I thought not on it so much any more. But he came out thither—he said that he repented, he would have had me now, had I been unwedded—he loved me. He said so. God knows if he said true. When he was gone—I dared not go out on the fjord, dared not for my sin, not with the child. And I had begun—I had begun to love you so!” She cried out, a single cry of the wildest pain. The man turned his head quickly towards her.

“When Björgulf was dying—Oh, no one, no one had to me than my life. When he lay in the death-throes—I thought, if he died, I must die too. But I prayed not God to spare my boy’s life—”

Lavrans sat a long time silent—then he asked in a dead, heavy voice:

“Was it because I was not his father?”

“I knew not if you were,” said Ragnfrid, growing stiff and stark where she sat.

Long they sat there in a deathly stillness. Then the man asked vehemently of a sudden:

“In Jesus name, Ragnfrid—why tell you me all this—now?”

“Oh, I know not!” She wrung her hands till the joints cracked. “That you may avenge you on me—drive me from your house—”

“Think you that would help me—” His voice shook with scorn. “Then there are our daughters,” he said quietly. “Kristin—and the little one.”

Ragnfrid sat still a while.

“I mind me how you judged of Erlend Nikulaussön,” she said softly. “How judge you of me, then—?”

A long shudder of cold passed over the man’s body—yet a little of the stiffness seemed to leave him.

“You have—we have lived together now for seven and twenty years—almost. ’Tis not the same as with a stranger. I see this too—worse than misery has it been for you.”

Ragnfrid sank together sobbing at the words. She plucked up heart to put her hand on one of his. He moved not at all—sat as still as a dead man. Her weeping grew louder and louder—but her husband still sat motionless, looking at the faint grey light creeping in around the door. At last she lay as if all her tears were spent. Then he stroked her arm lightly downward—and she fell to weeping again.

“Mind you,” she said through her tears, “that man who came to us one time, when we dwelt at Skog? He that knew all the ancient lays? Mind you the lay of a dead man that was come back from the world of torment, and told his son the story of all that he had seen? There was heard a groaning from Hell’s deepest ground, the querns of untrue women grinding mould for their husbands’ meat. Bloody were the stones they dragged at—bloody hung the hearts from out their breasts—”

Lavrans was silent.

“All these years have I thought upon those words,” said Ragnfrid. “Every day ’twas as though my heart was bleeding, for every day methought I ground you mould for meat—”

Lavrans know not himself why he answered as he did. It seemed to him his breast was empty and hollow, like the breast of a man that has had the blood-eagle carven through his back. But he laid his hand heavily and wearily on his wife’s head, and spoke:

“Mayhap mould must needs be ground, my Ragnfrid, before the meat can grow.”

When she tried to take his hand and kiss it, he snatched it away. But then he looked down at his wife, took one of her hands and laid it on his knee, and bowed his cold, stiffened face down upon it. And so they sat on, motionless, speaking no word more.

END