VII

TENERIFFE (continued)

MANY visitors to Teneriffe find their way across the mountains from Orotava to Guimar in the course of the winter or spring, which is the best time for the expedition. Though the actual time required for the journey from point to point may be only about seven hours, according to the condition of the road, it is best to make an early start and to have the whole day before one, so as to have plenty of time to rest on the way and enjoy all there is to be seen.

Once the last steep streets of the Villa Orotava are left behind the country at once changes its aspect. The banana fields, which have become somewhat monotonous after a long stay in their midst, have vanished, the air is cooler, and in the early morning the ground is saturated with dew. In spring the young corn makes the country intensely green, and the pear and other fruit blossoms lighten up the landscape, while in the hedge-rows are clumps of the little red Fuchsia coccinea, and great bushes of the common yellow broom. Here and there the two Canary St. John’s worts, Hypericum canariensis and H. floribundum, are covered with berries, their flowers having fallen some months before. Ferns and sweet violets grow on the damp and shady banks, and occasionally fine bushes of Cytisus prolifer were to be seen smothered with their soft, silky-looking white flowers. Gradually the region of the chestnut woods is reached, but these having only dropped their leaves after the spell of cold weather early in January, are still leafless, and it is sad to see how terribly the trees are mutilated by the peasants. Though not allowed to fell whole trees, the law does not appear to protect their branches, and often nothing but the stump and a few straggling boughs remain, the rest having been hacked off for firewood. Small bushes of the white-flowered Erica arborea soon appear, and the showy rose-coloured flowers of Cistus vaginatus were new to me.

At a height of about 3800 feet the level of the strong stream called Agua Mansa is reached, and though it is not actually on the road to Guimar many travellers make a short détour to visit the source of the stream and the beautifully wooded valley. The absence of woods in the lower country no doubt makes the vegetation on the steep slopes of the little gorge doubly appreciated. Many narrow paths lead through the laurel and heath, and on the shady side of the valley the extreme moisture of the air has clothed the stems of the trees with grey hoary lichens. The luxury of the sound of a running stream is rare in Teneriffe and one is tempted to linger and enjoy the scene under a giant chestnut tree, which has shaded many a picnic party from the Puerto.

By retracing one’s steps for a short distance the track is regained; Pedro Gil looms far ahead and the long steep ascent begins, up the narrow mule path among thickets of the tree heaths. Here these heaths are merely shrubby, not the splendid specimens which may be seen near Agua Garcia, where they are protected from the charcoal-burners, but the wide stretches covered with white flowers are very lovely appearing through the mist, which even on the finest day is apt to sweep across occasionally. The vegetation on these Cumbres is much the same as that which is passed through on the way to the Cañadas, and in spring the Adenocarpus viscosus or anagyrus, its tiny yellow flowers growing among the small leaves which crowd the branches, is about the last sign of plant life. Above this region are merely occasional patches of moss which live on the moisture of the mist which more often than not enwraps these heights. In clear weather, the long and rather tedious scramble of the last part of the road is soon forgotten in the delight at the magnificent view at the end. The top of the pass, 6800 ft., is like the back-bone of the island, and on the one side the whole valley of Orotava lies stretched below, with the Peak standing grand and majestic on the left, and on the other side lie the slopes down to the pine woods above Arafo. It is hard to agree with a writer who describes the scene as one of “immense desolation and ugliness, the silence broken only by the croaking voice of a crow passing overhead.” It is just this silence and stillness which appeals to so many in mountain regions; there is something intensely restful yet awe-inspiring in the complete peace which reigns in high altitudes in fair weather.

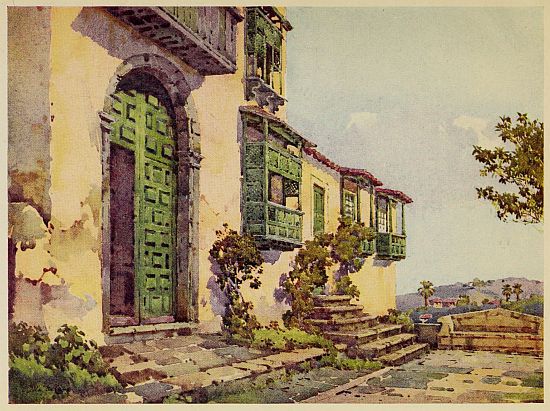

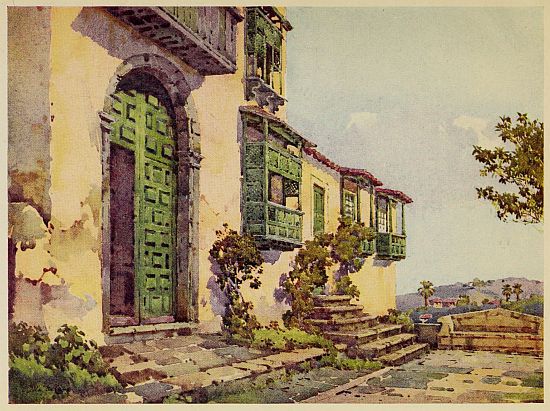

CONVENT OF SANT AUGUSTIN, ICOD DE LOS VINOS

A long pause is necessary to rest both man and beast, as not only is the path a long and trying one, but it is possible for the sun to be so extremely hot even at that altitude that it seems to bake the steep and arid slopes of lava and volcanic sand, and the loose cinders near the end of the climb make bad going for the mules. The so-called path becomes almost invisible except to the quick eye of the mules, accustomed as they are to pick their way across these stretches of loose scoriæ. Often the question “Which is the way?” is met by the owner of the mule answering “Il mulo sabe” (the mule knows), instead of saying, “To the right” or “To the left,” and I generally found he was right.

Many people prefer the ascent to the descent, and certainly though I have nothing but praise for mules as a means of locomotion going uphill, there are moments when I preferred to trust to my own legs going down the loose cindery track.

The fact that the eastern mountain slopes are warmer and drier, as the rainfall is not so great, encourages the vegetation to rise to a much higher altitude and the barren world of lava and cinders is sooner left behind. Our old friend the Adenocarpus soon greeted us, like a pioneer of plant life, and gradually came the different regions of pine, tree heaths, laurels, and then the grassy slopes.

The gorge known as the Valle is described as “one of the most stupendous efforts of eruptive force to be seen in the world, the gap appearing to have been absolutely thrown into space.” A network of what might well be mistaken for dykes seems to cut up the surface, and the whole formation of the Valle is of great interest to geologists. To the ordinary observer it is certainly suggestive of a desolate waste, and the black hill known as the Volcan of 1705 does not help to give life to the scene. The white lichen, which is the true pioneer of plant life, is only beginning to appear, though in crevices where deep cracks in the lava have probably exposed soil below the sturdy Euphorbias are getting a hold, and a few other robust plants, such as the feathery Sonchus leptocephalus, which I have always noticed seems to revel in lava. Possibly another century may make a great difference to the scene, but certainly during the past two hundred years there has not been much sign of returning vegetation, and the fiery stream has done its work thoroughly. The relief is great at once more reaching the pine woods above Arafo, and the fatigue, not peril, of the descent being over it is pleasant to find the comfort of the well-named Buen Retiro Hotel at Guimar.

Though over a thousand feet above the sea, the situation is so sheltered that Guimar boasts of one of the best and sunniest climates in Teneriffe, the little village lying as it were in a nest among the hills. The flowery garden of the hotel tells its own tale, better than any advertisement or guide-book, and a week may be spent exploring the various barrancos in the neighbourhood, especially by botanists, or lovers of plants. The Barranco del Rio is renowned as being about the best botanical collecting ground in the island. Dr. Morris says he found there no fewer than a hundred different species of native plants, many of which he had not seen elsewhere. The dripping rocks are clothed with maiden-hair fern, and the giant buttercup, Ranunculus cortusæfolius, appears to revel in the damp and the high air. The Barranco Badajoz is perhaps wilder and more precipitous; in places the rocky walls of these gorges rise to 200 ft., and appeal immensely to those who enjoy wild scenery. The lack of a roaring river tumbling down them I never quite got over, during all my stay in Teneriffe. Perhaps in a bygone age they existed, and owing to some eruption cracks were formed and the water vanished, as the bed of the stream seems to be there, but, alas! no water or only a trickling stream. The tiniest stream has to be utilised to provide water for a village below or for irrigation purposes, and this, combined with the deforestation of the island, no doubt has helped to drain the barrancos. There is more water in the Guimar ravines than in most, and from the Barranco del Rio or the Madre del Agua I should imagine the whole water-supply of the village is derived.

Those who are interested in relics should visit Socorro, about an hour distant from Guimar, the original home of the miraculous image of the Virgin de Candelaria. So celebrated was this image that nearly a whole book on the subject has been issued by the Hakluyt Society, edited and translated from old documents by Sir Clement Markham. The image is supposed to have been found in about the year 1400, by some shepherds, standing upright on a stone in a dry deserted spot near the sandy beach. A cross was afterwards erected by Christians when the Spaniards occupied the island to mark the spot, and in front of it was built the small hermitage called El Socorro. One shepherd saw what he supposed to be a woman carrying a child standing in his path, and as the law in those days forbad a man to speak to a woman alone in a solitary place, on pain of death, he made signs to her to move away in order that he and his sheep might pass. No notice being taken and no reply made, he took up a stone in order to hurl it at the supposed woman, but his arm became instantly stiff, and he could not move it. His companion, though filled with fear, sought to ascertain whether she was a living woman, and tried to cut one of her fingers, but only cut his own, and did not even mark the finger of the image. These accordingly were the two first miracles of the sacred figure.

These shepherds related their experiences to the Lord of Guimar, who after being shown the stiff arm and cut fingers of the men, summoned his councillors to consult as to what had best be done. Accompanied by his followers and guided by the shepherds, he came to the spot and ordered the shepherds to lift the figure, as it apparently was no living thing, and to remove it to his house. On approaching the image to carry out their Lord’s orders, the stiff arm of the one and the cut fingers of the other instantly became cured. The Lord and his followers were so struck with the strange and splendid dress of the woman, who was now invested as well with supernatural powers, that they lost their first terror. Determined to do honour to so strange a guest within his dominions, the Lord of Guimar raised the image in his arms and transported it to his own house.

Unbelievers say that the image was merely the figure-head of a ship which was washed up on the beach, but the faithful maintain that so beautiful was the image, so gorgeous its apparel and so brilliant the gold with which it was gilded, that it was the work of no human hands, and contact with the sea would have destroyed the brilliancy of its colouring.

The Lord of Guimar sent the news of the wonderful discovery to the other chiefs in the island, offering that the image, evidently endowed with supernatural and healing powers, should spend half the year within the territory of the Lord of Taoro. This offer was declined, but the chief came with many followers to see the new wonder, which was set up on the altar in a cave and guarded with great care. For some forty years the image remained in the care of infidels, who regarded it with great awe, and then it fell to the lot of a boy named Auton, who had been converted to Christianity by the Spaniards, to enlighten the natives as to the nature of their treasure. On being shown the figure he instantly recognised it as being a representation of the Virgin, and after having prayed before it, he instructed the natives in the story of the Virgin Mary. The boy was in return made sacristan of the image and it was guarded day and night. At certain intervals visions of processions on the beach were seen and remains of wax candles were found, and a shower of wax upon the beach was supposed to have been sent to provide wax for candles to be burnt in honour of Our Lady of Candelaria.

The neighbouring islands soon heard tales of the holy relic and the inhabitants came to visit it. For several centuries wonderful miracles were at different times ascribed to it, and it continued to be regarded with the deepest reverence, though the housing and care of the image was the cause of various feuds, and on one occasion it was stolen and carried away to Fuerteventura, but was returned.

Unfortunately, during a great storm in 1826, the holy relic was swept away into the sea, and thus was the original Virgin de Candelaria lost, and though a new image was made and blessed by the Pope it has never been regarded with quite the same awe and reverence, though many pilgrims visit the church on August 15, the feast of Candelaria, and again on February 2.