VIII

GRAND CANARY

I HAVE noticed that there is always a certain amount of jealousy existing between the inhabitants of a group of islands. In old days they were of course absolutely unknown to each other, and even spoke such a different language that they had some difficulty in making themselves understood. Though such is naturally not the case to-day when in a few hours the little Interinsular steamers cross from one island to another, still in Teneriffe you are apt to be told there is nothing to be seen in Grand Canary, or if you happen to visit Las Palmas first you will probably be told you are wasting your time in proposing to spend some weeks or months in Teneriffe or in even contemplating a flying visit to the other islands.

It was with a feeling of great curiosity that I watched our approach to Grand Canary, as one evening late in May our steamer crept round the isthmus known as La Isleta and glided into the harbour of Puerto de la Luz. Many towns look their best from the sea and this is perhaps especially true of Las Palmas. The sun was setting behind the low hills which rise above the long line of sand dunes, dotted with tamarisks, running between the port and the isleta, and in the evening light the town itself, some three miles away, looked far from unattractive, its cathedral towers rising above the palm trees on the shore.

On landing the illusion is soon destroyed; the dust, which is the curse of Las Palmas, was being blown gaily along by the north-east wind, which seems to blow perpetually, and the steam tram which connects the port and the town was grinding along, emitting showers of black smoke, and I began to think the writer was not far wrong who said Las Palmas was “a place of barbed wire and cinders.”

Most travellers’ destination is the hotel at Santa Catalina, lying midway between the port and the town, and here many of them remain for the rest of their stay, not being tempted ever to set foot outside the pleasant grounds and comfortable hotel, except possibly to play a game of golf on the links above, which are a great attraction and boon to those who are spending the winter basking in the sunshine in search of health.

The island appears to have altered its name from Canaria to Gran Canaria because of the stout resistance offered by the natives, who called themselves Canarios, to the Spanish invasion. The original name is said to have had some connection with the breed of large dogs peculiar to the island, though none appear to exist now. As regards the shape of the island the following is a very good description: “The form of the island is nearly circular, and greatly resembles a saucerful of mud turned upside down, with the sides furrowed by long and deep ravines. The highest point is a swelling upland known as Los Pechos, 6401 ft.” I own that as I approached the island there was a curious sense of something lacking, something missing, and then I realised that we were no longer to live under the shadow of the Peak, that an occasional distant glimpse is all we should see of the great mountain which we had grown to look on as a friend.

The nearest object of interest to the hotel is the Santa Catalina fountain, where in August 1492, after praying in the chapel, Christopher Columbus filled his water-barrels with a store of water which was to last him until the New World was sighted. Columbus on each of his expeditions touched at the Canaries; but at the very outset of his first voyage, one of his ships having lost her rudder and suffered other damage in storms encountered on the way, Columbus cruised for three weeks among the islands in search of another vessel to replace his caravel. Though he heard rumours of three Portuguese caravels hovering off the coast of Ferro (now called Hierro) three days’ calm detained him, and by the time he reached the neighbourhood where the ships had been seen, they had vanished, and repairing his rudder as best he could he started in search of an unknown land, eventually reaching one of the Bahama group. Columbus’ next visit to the Canaries was on his second voyage of discovery, when he again called at the islands, this time taking wood, water, live stock, plants and seeds to be propagated in Hispaniola, where he had already been so struck with the beautiful and varied vegetation. In the town of Las Palmas an old house is pointed out as the house where Christopher Columbus died; but I am afraid, if we are to believe historians, this is merely a flight of the imagination. In Washington Irving’s “Life of Columbus” we are told that he died at Seville surrounded by devoted friends, and a note says: “The body of Columbus was first deposited in the convent of St. Francisco, and his obsequies were celebrated with funereal pomp in the parochial church of Santa Maria de la Antigua, in Valladolid. His remains were transported in 1513 to the Carthusian convent of Las Cuevas, in Seville. In the year 1536 the bodies of Columbus and his son Diego were removed to Hispaniola and interred by the side of the grand altar of the cathedral of the city of San Domingo. But even here they did not rest in quiet; for on the cession of Hispaniola to the French in 1795 they were again disinterred, and conveyed by the Spaniards with great pomp and ceremony to the cathedral of Havanna in Cuba, where they remain at present.”

One of the easiest expeditions from Las Palmas is along the main road to the south of the island, either driving or by motor. Long stretches of banana fields provide the fruit for the English market, which finds its way daily on to the mole: and in spring hundreds of carts, with potato-boxes labelled “Covent Garden,” come from the same district. A little way before reaching the village of Tinama, which is built amid desolate surroundings of lava and black cinders, the road passes through a tunnel, which must have been somewhat of an undertaking to bore, and then a vast bed of lava crosses the road. Here some huge clumps of Euphorbia canariensis show that this plant is not peculiar to any one island, but is equally at home on any bed of lava or cliff.

Telde, famous for its oranges—said to be the best in the world—is not a very interesting town; but from a little distance, combined with the almost adjoining village of Los Llanos, its Moorish dome amid groves of palm trees, and scattered groups of white houses, make it unlike most other Canary towns. The celebrated orange groves are some distance off, and it is feared that so little care is taken of the trees that the disease and blight which have ravaged nearly all the groves in the archipelago will soon attack these. The disease could be kept at bay by insecticides and combined effort, but it is no use for one grower to wage war against the pest, if his neighbour calmly allows it to get ahead in his groves, though the excellence of the oranges makes it seem as if they deserved more care. If disaster overtakes the banana trade—and already I heard whispers of grumbling at the absurd price of land, and rumours of as good land and plenty of water to be had on the West Coast of Africa, where labour is half the price—possibly orange-growing may be taken up by men who have learnt their experience in Florida, and by careful cultivation another golden harvest may be reaped.

The ultimate destination of most travellers in this direction is the Montaña de las Cuatro Puertas (the Mountain of the Four Doors), which is a most curious and interesting example of a native place of worship. The Canarios seem to have been especially fond of cave-dwellings, which are very common in Grand Canary, though they are by no means unknown in the other islands; and it is no unusual thing to find districts where a scanty population is troglodytic in habit, living entirely in cave-dwellings scooped out of the soft sandstone rock. Some families have quite a good-sized though strange home, and besides rooms with whitewashed walls are stables for goats or mules. One writer says: “The hall-mark of gentility in troglodyte circles is the possession of a door. This shows that the family pays house tax, which is not levied upon those who live the simpler life, and are content with an old sack hanging across the open doorway.”

Webb and Berthelot, in their “Histoire Naturelle,” seem to have been much struck by these cave-dwellings, and the following account appears in their description of the Ciudad de las Palmas: “The slopes above the town on the west are pierced by grottoes inhabited by families of artisans; narrow paths have been made in the face of the cliffs by which to get to these excavations. After sunset, when the mountain is in deep shadow, the troglodyte quarter begins to light up, and all these aerial lights, which shine for a moment and then instantly disappear, produce the most curious effect.” The “Mountain of the Four Doors” is of much larger dimensions than any ordinary cave-dwelling, as the whole mountain appears to have been excavated, and would certainly have made a very draughty dwelling, as the four entrances which give the mountain its name are only separated by columns, thus allowing free entrance to the wind. The sacred hill is said to have been partly occupied by embalmers of the dead, the mummies being eventually removed to the burial cave on one side. Another side of the hill was the residence of the Faycans, or priests, who conducted the funeral ceremony; and there were the consecrated virgins, or harimaguedas, who were here kept in the strictest seclusion for years, employed in the gruesome occupation of sewing the goat-skins for wrapping up the mummies. The Canarios appear to have regarded a shelf in the burial cave running north and south as being the most honourable position, and on these they placed the bodies of highest rank, judging from the mummies found on them, as the leather is often richly embroidered, and the greatest care was taken in embalming the bodies. The inferiors were laid east and west. Any one who is interested in the study of the Canary mummies will find much to interest them in the Museum in Las Palmas, which is said to be richer in remains of aboriginals than any other museum in the world. Here may be seen rows of mummies in glass cases, some curious pottery, and the Pintaderas, or dyes, which were used to stamp designs on the skin or leather.

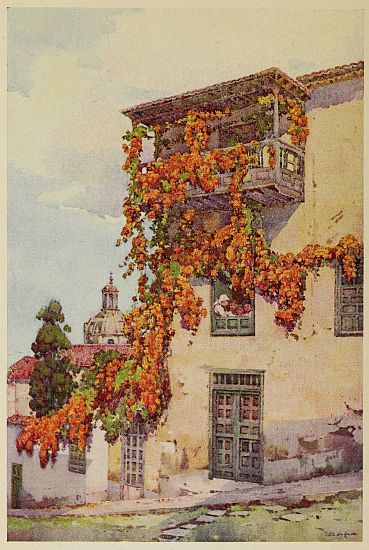

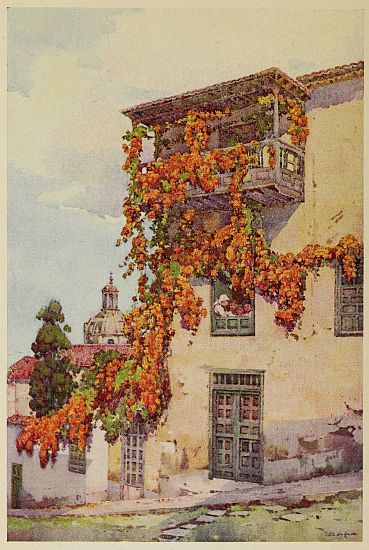

AN OLD BALCONY

In the same museum the sight of the fearsome “devil-fish,” in the room devoted to local fishes, must, I think, have made many visitors from Orotava shudder to think of the light-hearted way in which they had gaily bathed on the Martianez beach—an amusement I often considered dangerous from the strength of the breakers and the strong undercurrent; but when added to this I was assured the monster, which is said to embrace its victims and carry them away under water after the manner of the octopus, was “not uncommon round the Canaries,” I was thankful to think I had never indulged in bathing.