X

GRAND CANARY (continued)

THOSE who do not mind a long day and really early start can see a good deal of the country and make some very beautiful expeditions without facing the terrors of the native inn. When even our guide-book—and the writer of a guide-book is surely bound to make the best of things—warns the traveller that the “accommodation is poor,” or that “arrangements can be made to secure beds,” every one knows what to expect. So a long day, however tiring, is preferable, if it is possible to return the same night.

A drive of two hours leads to San Mateo, where good accommodation would be a great boon, as it is a great centre for expeditions, besides being beautifully situated near chestnut and pine woods. A rough mule track leads in something under three hours to the Cruz de Tejeda, which is about the finest excursion in the island. Good walkers will probably prefer to trust their own legs rather than the mule’s; but it is a stiff climb, as the starting-point, San Mateo, is only some 2600 ft. above the sea, while the Cruz is 5740 ft. Without descending into the deep Barranco which leads down to Tejeda itself, in clear weather the view is magnificent. That most curious isolated rock, the Roque Nublo, stands like a great pillar or obelisk, pointing straight into the heavens, rising 370 ft. above all its surroundings, and more than 6000 ft. above sea-level, and is often clearly visible from Teneriffe. The great valley of Tejeda lies stretched before the traveller, who is surely well rewarded for his climb by the splendid panorama. Deep precipitous ravines full of blue shadows lie in vast succession in front, and to the right the cultivated patches in the valley are a bright emerald green from the young corn, and over the deep blue sea beyond, towers the great Peak of Teneriffe, looking most majestic and awe-inspiring rising above the chain of high mountains which are veiled in a light, mysterious mist. Never, perhaps, is the great height of the mountain so well realised, as it stands crowning a picture which our guide-book tells us is “never to be forgotten, and second to none in Switzerland or the Alps.”

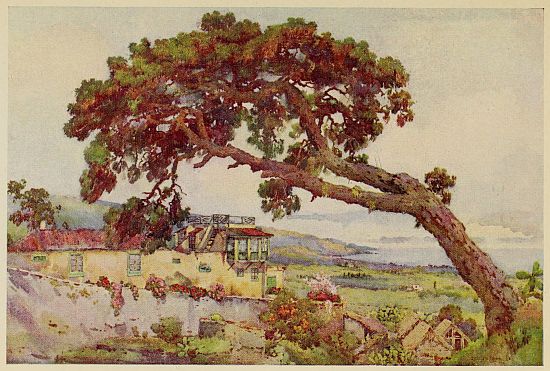

THE CANARY PINE

Another favourite expedition for the energetic is to the Cumbres, particularly for those who are bent on reaching the highest land in the island. The Pico de los Pechos is the highest point (6400 ft.), but the Montaña de la Cruz Santa, on the left, is generally chosen, as here parties of walkers and riders can meet, under the shadow of the Holy Cross, where, on the festivals of St. Peter and St. John, a religious fiesta is held. Before the wholesale deforestation took place, this district must certainly have been much more beautiful; now it is a silent, shadowless world, a desolate region of stony ground, over which run great barrancos looking like deep rents in the mountain sides. Probably no other island has suffered more cruelly from the axe of the charcoal-burner, and in the neighbourhood of Las Palmas everything has been cut which could be converted into charcoal, and nowadays that necessary article of life to the Spaniard has to be imported.

One of the most beautiful of all their native forests, the forest of Doramas, is hardly worthy of its name at the present time; scattered trees on the mountain side are all that remains of one of the most beautiful of primeval forests, which was so celebrated in the days of the Canarios. Even in 1839, when Barker Webb and Berthelot visited the forest, they lamented over the destruction of the trees, and whole stretches of country which had formerly been pine and laurel woods were only covered with native heath. The prince Doramas, who is said to have lived in a grotto in the picturesque neighbourhood of Moya, gave his name to the mountain and forest, and these travellers visited his cave, which was still regarded with great veneration on account of the tales of the heroic and brave deeds and almost superhuman strength of the prince, which had been handed down from generation to generation. They found the door, or rather entrance, to the grotto draped with garlands of Hibalbera (Ruscus androgynus) and the scarlet-flowered Bicacaro of the Guanches (Canarina campanulata), as the spot was then solitary and deserted. Some years before the Spanish traveller Viera had been charmed by the beauty of the forest, and a translation of passages from his work on the “General History of the Canary Islands” will show what a treasure the Spaniards have lost in allowing the destruction of the woods.

“Nature,” he says, “is here seen in all her simplicity, nowhere is she to be found in a more gay or laughing mood; the forest of Doramas is one of the most beautiful of the world’s creations from the variety of its immense straight trees, always green and scattering on all sides the wealth of their foliage. The sun has never penetrated through their dense branches, the ivy has never detached itself from their old trunks; a hundred streams of crystal water join together in torrents to water the soil which becomes richer and richer and more productive. The most beautiful spot of all in the depth of this virgin forest is called Madres de Moya; the singing of the birds is enchanting, and in every direction run paths easy of access; one might believe them to be the work of man, but they are all the more delightful because they are not. By following one of these paths one comes to the spot called by the Canarios, the Cathedral, an immense and complete dome of verdure formed by the meeting of the branches of the magnificent trees. Laurels raise their great trunks in colonnades, with their branches interlaced and bent into gigantic arcades, which produce a most marvellous effect. Advancing under their majestic shadow one discovers at every turn fresh views, and one’s imagination, carried away by the tales of the ancients, is filled with poetic impressions. These enchanted regions are well worthy of the fictions of fables, and in the enthusiasm they give birth to when wandering in their midst, the Canarios appear to have lost nothing of their celebrity; these are still the Fortunate Islands and their shady groves the Elysium of the Greeks, the wandering place of happy souls.”

The poet Cayrasco de Figueroa, who was known as the “divin Poête,” and whose tomb is to be seen in one of the side chapels of the cathedral in Las Palmas, wrote verses in praise of the forest, which he must have seen in all its glory in 1581, and some fifty years later the venerable don Christobal de la Camara, Bishop of Grand Canary, travelled all through it and wrote of “the mountain of d’Oramas as one of the marvels of Spain: the different trees growing to such a height that it is impossible to see their summit: the hand of God only could have planted them, isolated among precipices and in the midst of masses of rock. The forest is traversed by streams of water and so dense are its woods, that even in the days of greatest heat the sun can never pierce them. All I had been told beforehand of its beauties appeared fabulous, but when I had visited it myself I was convinced that I had not been told enough.”

Between 1820 and 1830 the forest seems to have suffered much. At the former date some part of the woods remained in all their pristine beauty on the Moya side and the great Til (Laurus fœtens) trees round Las Madres were still standing, but ten years later, when Barker Webb and his companion visited this spot again, these splendid trees were shorn of their finest branches and the devastation of the woods had begun.

Long before this date the mountain appears to have become an apple of discord. Some influential landed proprietors demanded the division of the forest, the communes interfered, and eventually the question became a political one. Just as a settlement was arrived at the party in power fell and General Morales arrived on the scene, having been granted a large part of the forest by Ferdinand VII. in recognition of his services, and the deforestation of the district began in earnest, in spite of local resistance to the royal decree.

In most of the islands some old pine has been given the name of the Pino Santo, and protected by a legend of special sanctity, but perhaps the Pino Santo of Teror was the most venerated of all. The tree, old historians tell us, was of immense size and grew adjoining the Chapel of Our Lady; so close, in fact, that one of its branches served as the foundation of the belfry. The unsteadiness of this strange foundation not unnaturally hastened the destruction of the little tower, and on April 3, 1684, the sacred tree, which collapsed from its great age and weight, threatened to crush the chapel beneath. The sacred image of Our Lady of the Pine was so named because it was said to have been found in the branches of the tree. This miraculous discovery was made after the conquest in 1483. The Canarios had often observed a halo of light round the tree which they did not even dare approach, but Don Juan de Frias, bishop and conqueror, more courageous than the rest, climbed into the branches of the tree and brought down a statue of the Virgin. He is said to have found the image among thick branches and between two dragon trees, nine feet high, which were growing out of a hollow in the pine branches. The figure at once received the name of Nuestro Señora del Pino, the church, which has been built on the site of the old chapel, being dedicated to her. The spot on which stood the sacred tree is now marked with a cross, and a pine tree close by is said to be a descendant of the Pino Santo. Nor is this all the legend about this wonderful tree. A spring of healing water issued from beneath it, and here the faithful came to bathe and be healed of their ills. An avaricious priest thinking he would collect fees or alms from those who came to visit the spring, caused it to be enclosed by masonry and a door, which he kept locked, upon which the sacred spring dried up, and his schemes were defeated. Below the village to this day are some mineral springs dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes. Who knows, possibly this is the same sacred spring which has reappeared to benefit the sick.