IX

GRAND CANARY (continued)

MANY of the residents of Las Palmas move to the Monte for the summer, but even in late spring most people are glad to get away from the town and the white dust, which by then is lying ankle deep on the roads. Monte is the only other place which the ordinary traveller will care to stay in, as the native inns in Grand Canary bear a bad reputation for discomfort and dirt, and the Monte makes a good centre for expeditions, besides being an entire change of air and scene.

The last part of the drive up from the town which is only some six or seven miles, affords good views of the lie of the land and makes one realise the immense length of the barrancos in this island. It appears never to be safe to assert the name of a barranco, as it is not uncommon for one ravine to have four or five different names in the course of its wanderings towards the sea. The great barranco one looks down into from the road beyond Tafira is called at this point the Barranco del Dragonal.

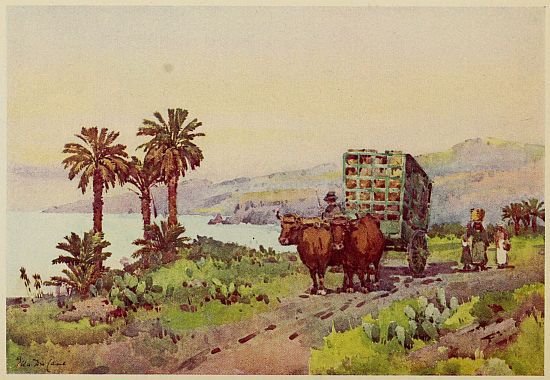

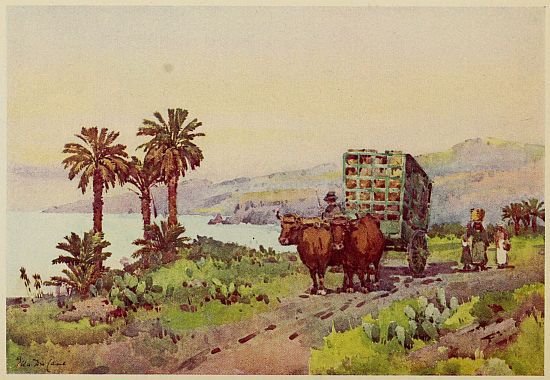

A BANANA CART

A century ago this district was a mere expanse of cinders interspersed with the usual Canary plants which find a home in the most desolate of lava beds. Clumps of Euphorbias and its two inseparable companions, the miniature dragon tree, Senecio Kleinia, and the graceful Plocama pendula broke the monotony of the grey lava. Now the scene has changed and this once desolate region has been transformed into one of the most fertile districts of the island. On the terraced slopes vines flourish, whose grapes produce the best red Canary wine. Footpaths bordered with flowers lead through these countless acres of vineyards, recalling the fashion in Teneriffe of the flower borders, passeios, which lead through many of the banana plantations, showing that the owner of the land still had some soul for gardening and a love of flowers, as he spared a strip of the precious soil for flowers. Many an alley in early winter is gay with rows of poinsettias feeding and flourishing on the water and guano which is given to the crop with a lavish hand, or rows of scarlet and white geraniums flank rose trees, interspersed here and there with great clumps of white lilies. The country in late spring is fragrant and gay from the bushes of Spanish broom (Spartium junceum) which edge the lanes; their yellow blossoms are in charming contrast to the soft grey-green of the old agaves, which make such excellent hedges.

Just behind the Monte lies the great basin of the Caldera. It is best seen from the Pico de Bandama, a hill 1840 ft., which not only commands an excellent view of the crater, but of all the country round. The Gran Caldera de Bandama, a vast complete basin with no outlet, is over a mile across and 1000 ft. deep, and consequently is one of the most perfect craters in the world. The walls are formed of rocks and here and there vivid bits of colouring speak for themselves of its origin, and round the edge are layers of cinders. It is to be hoped that it will not some day come to life again and throw up a peak, as the basin of the Cañadas is supposed to have thrown up the great cone of the Peak of Teneriffe. It looks peaceable enough to-day, a mule track leading down into it. At the bottom of the crater vines are cultivated, and a farmer calmly lives on what was once a boiling cauldron.

The vines seem to thrive in the volcanic soil, their roots go down deep in search of damper loam below, and this possibly helps to keep them free of disease, though in spring the effect of the tender green shoots with their long twining tendrils is sadly spoilt when, just as they are coming into flower, the mandate goes forth to dust the growth with sulphur. The men and women, who for the past weeks have been busy gathering in the potato crop, are now employed in sulphur dusting. For two months or more whole families are engaged with the potato harvest; the rows are either ploughed up with a primeval-looking plough, or hoed with the broad native hoe, which does duty for spade or fork in this country, and then the potatoes are collected with great rapidity, even the smallest member of the family helping, sorted and packed in deal boxes holding each some 60 or 70 lb., with a layer of palm fibre on the top, and shipped to England. It is well known that Canary new potatoes do not command a very good price in the English market, and I often wondered whether it is not the kind which is at fault. Kidney potatoes, which are regarded in England as the best for new potatoes, are hardly ever grown, the Spaniards regarding them with horror and loathing, and though English seed is imported annually, the result to my mind seemed unsatisfactory, as I never came across any young potatoes worthy of the name “new potatoes.” Possibly the soil and climate are unsuited, and there is a tendency I was told in all varieties to excessive growth, and no doubt the green peas and broad beans, which are most suited to English soil, often here grow to mammoth proportions, giving a poor result as a crop, and it is only experience which proves which are the varieties best suited to the climate and soil. The peas which are grown from seed ripened in the island degenerate to tasteless, colourless specimens, producing tiny pods, with at the outside three peas in them, and the French beans have the same lack of flavour when grown from native seed.

Potatoes and tomatoes are both unfortunately liable to disease, and in some seasons the whole crop is lost. The same disease appears to affect both crops. Dr. Morris, when he visited the islands, thought seriously of the outlook, unless systematic action was taken. He says: “There is a remedy if carefully applied and the crop superintended, but the islanders seem to regard the trouble with strange indifference, and go on the plan of ‘If one crop fails, then plant another.’”

The volcanic soil appears to suit cultivated garden plants, as well as vines, bananas and potatoes, and the gardens in the neighbourhood of Telde are a blaze of colour and have a wonderful wealth of bloom in May, which is essentially the “flower month” in all the islands. Earlier in the winter it is true the creepers will have been at their best, and by now the last trumpet-shaped blooms will have fallen from that most gorgeous of all creepers, Bignonia venusta, and the colour will have faded from the bougainvilleas, red, purple, or lilac, though they seem to be in almost perpetual bloom. Allemandas flourish even at this higher altitude, as does Thumbergia grandiflora, another tropical plant. Though its bunches of grey-blue gloxinia-like blooms are beautiful enough individually, it is sadly marred by the dead blossoms which hang on to the bitter end and are singularly ugly in death, not having the grace to drop and leave the newcomers to deck the yards of trailing branches, with which the plant will in an incredibly short time smother a garden wall or take possession of and eventually kill a neighbouring tree. Roses seem to flourish and bloom so profusely that the whole bush is covered with blossoms, and a garden of roses would well repay the little care the plants seem to require. The Spaniards prefer to prune their roses but once a year, in January, but by pruning in rotation roses could be had all the year round, and certainly half the trees should be cut in October, after the plants have sent up long straggling summer growth, and by January a fresh crop would be in flower. But the native gardener is nothing if not obstinate, and if January is the month for pruning according to his ideas, nothing will make him even make an experiment by cutting a few trees at a different season, and in this month are cut creepers, trees and shrubs, utterly regardless as to whether it is the best season or not.

In most gardens the trees comprise several different Ficus, the Pride of India (Melia Azedarach), many palms, oranges, mangos and guavas, lagerstrœmias, pomegranates and daturas, while flower-beds are filled with carnations, stocks, cinerarias, hollyhocks and longiflorum lilies, all jostling each other in their struggle for room. The country people struck me as having a much greater love of flowers here than in Teneriffe, where a cared-for strip of cottage garden or row of pot plants is almost a rare sight, and roof gardening is perhaps more the fashion. Geraniums and other hanging plants tumble over the edge of the flat roof tops, looking as though they lived on air, as the boxes or tins they are grown in are out of sight. Here the humblest cottager grew carnations, fuchsias, begonias, and pelargoniums with loving care in every old tin box, or saucepan, that he could lay hands on. One reason that pot plants are scarce is the enormous cost of flower-pots, which are mostly imported, and often if I wished to buy a plant, the price was more than doubled if the precious pot was to be included in the bargain. In May, the month especially consecrated to the Virgin Mary, all her chapels and way-side shrines are kept adorned with flowers. In the larger churches the altar and steps are draped with blue and white, and piled up with great white lilies whose heavy scent mingling with the incense is almost overpowering, but in the humbler shrines the offerings are merely the contributions of posies of mixed flowers, placed there probably by many a woman who is called after Our Lady. I was always struck by the number of way-side crosses and tiny shrines in many of which a lamp shines nightly, and yet I cannot say the people seemed to be either reverent or deeply religious, and I was never able to obtain an explanation of the crosses one came across in unexpected places, even in the branches of trees in the garden. At first I thought they must be votive offerings in memory of an escape from danger, possibly a child who had fallen from the tree and escaped unhurt, but the gardener merely said it was costumbre, the custom of the country, and offered no further information. On May 3, the Fiesta de la Cruz, every cross, however humble, is decked with a garland of flowers, which often hangs there until the feast comes round again, and in front of many of the crosses a lamp is lighted on this one night in the year.

On holidays and Sundays the women, especially those who are on their way to Mass, wore their white cashmere mantillas, and I inquired whether this also had any connection with “Our Lady’s” month of May, but I was told in old days they were the almost universal head-dress, a fashion which unfortunately is fast dying out. This appeared to be the only distinctively local feature of their dress, and the usual head-dress of the women and children, with bright-coloured handkerchiefs folded closely round the forehead and knotted in the nape of the neck, is common to all the islands. When the family is in mourning even the smallest member of the household wears a black handkerchief matching its bright black eyes, but the day I fear is fast approaching when battered straw hats will take their place, not the jaunty little round hats with black-bound brims, which every country woman wears to act as a pad for the load she carries on her head. For generations the women have carried water-pots and baskets which many an English working man would consider a crushing load, and no one can fail to admire their splendid carriage and upright bearing, as they stride along never even steadying their load with one hand. The only peculiarity of the men’s dress is their blanket cloaks; in some of the islands they are made of mantas woven from native wool, but as often as not an imported blanket is used, gathered into a leather or black velvet collar at the neck. On a chilly evening in a mountain village every man and boy is closely wrapped in his manta, often it must be owned in an indescribable state of filth. At night they do duty as a blanket on the bed, and in the day are dragged through dust or mud, but cleanliness is not regarded in Spanish cottages, where chickens, goats, and sometimes a pig all seem to share the common living-room.

AN OLD GATEWAY

I fear the few model dwellings which the tourist is invited to inspect at Atalaya (the Watch Tower) are not true samples of the average cottage or cave-dwelling. Atalaya was formerly a native stronghold, and one can quite imagine what formidable resistance the invaders must have met with from these primitive fortresses. The narrow ledges cut in the face of the cliffs made the approach to them almost inaccessible except to the Canarios, who appear to have been as agile as goats, and from the narrow openings showers of missiles could be hurled at the attackers. Atalaya at the present time is the home of the pottery makers. They fashion the local clay into pots with a round stone in just as primitive a way as did the ancient Canarios. They seem to live a life apart, and are regarded with suspicion by their neighbours, who rarely intermarry with them. The whole colony are inveterate beggars, old and young alike, but as tourists invade their domain in order to say they have seen “the most perfect collection of troglodyte dwellings in the Archipelago,” and request them to mould pots for their edification, it is perhaps not surprising that they expect some reward.