XII

GOMERA

GOMERA is seldom visited by tourists, but a flying visit can be paid to it during the stay of the inter-insular boat which plies between the islands. In summer its higher land and woods would be an ideal camping-ground for a traveller with tents, and the climate is said to be very good. The soil appears to be extremely rich and well repays the cultivator, but the Cumbres are still clad with beautiful woods, which up to now have escaped from the destructive charcoal-burners. The soil of the island is volcanic, but it is one of the few of the group which cannot boast of an old crater, and the highest point is only about 4400 ft. A remarkable feature of the vegetation is the entire absence of pines; there are none at the present time, and old historians always comment on their absence. This in itself showed ancient writers the approximate height of the island, as nowhere is the native Pinus canariensis found in its natural conditions under 4000 ft. above sea level, while in the region below that altitude Erica arborea flourishes. In Gomera the heaths attain larger dimensions than in any other island, and grow into real trees, and on the beautiful expedition from San Sebastian, the port, to Valle Hermoso (the Beautiful Valley), which appears well to deserve its name, the traveller passes through a succession of well-watered and wooded country and lovely forest scenery, said to be unsurpassed in the Canaries. San Sebastian was formerly of more importance than it is now, as in old days its naturally sheltered harbour was much valued by navigators.

It was probably for this reason that it became the favourite anchorage of Christopher Columbus on his voyages of discovery. He first called at Puerto de la Luz, in Grand Canary, in order to repair the damage done to one of his fleet, but leaving his lieutenant in charge of the damaged ship, Columbus himself sailed to Gomera on August 12, 1492. On this occasion he stayed for eleven days, returning to Grand Canary to pick up La Pinta, but he again called at Gomera on September 1. He appears to have spent a week in storing provisions, and several sailors from Gomera joined his expedition. On his second voyage he returned to his old anchorage, this time again picking up sailors, and as he had a much larger fleet of vessels under his command, besides plants and seeds he embarked cows, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens, all of which he wished to introduce to the country he had already discovered, a fact which has been of great interest to zoologists who had been puzzled to determine the true race of many animals found in the West Indies. Twice again he visited Gomera, so there is no doubt it was his favourite port of call. Some old historians assert that for a time he lived in Gomera. At San Sebastian an old house is still pointed out as having belonged to him. After his marriage in Lisbon with a daughter of the Portuguese navigator Perestrello, for some years little seems to be known of the admiral’s doings. The inhabitants of Madeira claim that he lived in a house in Funchal, while other writers affirm that he lived in Gomera and speak of his return to “his old domicile” after one of his voyages.

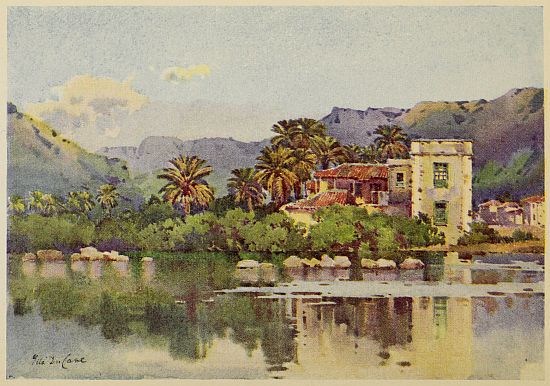

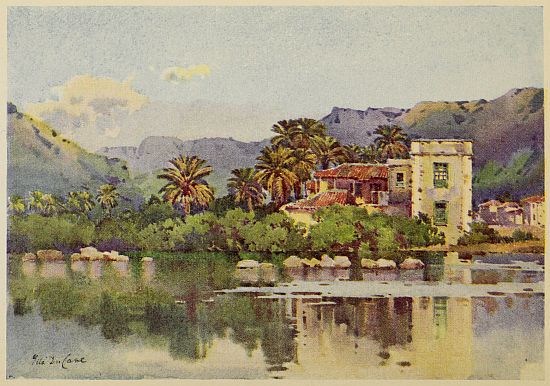

SAN SEBASTIAN

In old days the inhabitants were called Ghomerythes, and after the conquest of the island by the Spaniards, which did not prove a difficult matter, as though the islanders were a brave little band they knew little or nothing of the art of warfare, the conquerors enlisted the services of the natives to help them in attacking the other islands. The island was not left entirely undisturbed even after the conquest, as Sir Francis Drake made several attempts to take the island in 1585, and five years later a Dutch fleet under Vanderdoes invaded the town. On the walls of the quaint old church in San Sebastian are paintings showing the repulse of the Dutch fleet in the harbour in 1599. The Moors in the seventeenth century attacked and burnt a great part of the town.

A peculiarity of the island is the strange whistling language, which probably in ancient times was in universal practice, but is now more or less confined to one district, the neighbourhood of the Montaña de Chipude, being very rarely used by the natives in San Sebastian, who have most of them lost the art. The best whistlers can make themselves heard for three or four miles, and in the whistling district all messages are sent in this way, which no doubt is of the greatest convenience where telegrams are unknown and deep barrancos separate one village from another. The greatest adepts in the art do not use their fingers at all, and by mere intonations and variations of two or three notes a sufficiently elaborate language has been invented to enable a conversation to be carried on. The following may possibly be a traveller’s tale, but it shows the use which can be made of the language: “A landed proprietor from San Sebastian with farms in the south took lessons secretly. The next time he visited his tenants he heard his approach heralded from hill to hill, instructions being given to hide a cow here or a pig there, and so on, in order that he should not claim his medias or share of the same.” The writer of the above himself heard the following short message given: “There is a caballero here who wants a letter taken to San Sebastian. Tell Fulano to take this place on his way and fetch it.” This was at once understood and acted upon. If any doubt is held as to the accuracy of the message, the answer comes to repeat, and when understood the receiver answers back, “Aye, aye.” It is to be hoped that the practice will not entirely die out, as I believe the whistling language of Gomera is unique.