II

TENERIFFE (continued)

ABOUT a thousand feet above the Puerto de Orotava, on the long gradual slope which sweeps down from Pedro Gil forming the valley of Orotava, lies the villa or town of Orotava. This most picturesque old town is of far more interest than the somewhat squalid port, being the home of many old Spanish families, whose beautiful houses are the best examples of Spanish architecture in the Canaries. Besides their quiet patios, which are shady and cool even on the hottest summer days, the exterior of many of the houses is most beautiful. The admirable work of the carved balconies and shutters, the iron-work and carved stone-work cannot fail to make every one admire houses which are rapidly becoming unique. The Spaniards have, alas! like many other nations, lost their taste in architecture, and the modern houses which are springing up all too quickly make one shudder to contemplate. Some had been built to replace those which had been burnt, others were merely being built by men who had made a fortune in the banana trade. Not satisfied with their old solid houses, with their fine old stone doorways and overhanging wooden balconies, they are ruthlessly destroying them to build a fearsome modern monstrosity, possibly more comfortable to live in, but most offending to the eye. The love of their gardens seems also to be dying out, and as I once heard some one impatiently exclaim, “They have no soul above bananas,” and it is true that the culture of bananas is at the moment of all-absorbing interest.

Though the patios of the houses may be decked with plants, the air being kept cool and moist by the spray of a tinkling fountain, many of the little gardens at the back of these old family mansions have fallen into a sad state of disorder and decay. The myrtle and box hedges, formerly the pride of their owners, are no longer kept trim and shorn, and the little beds are no longer full of flowers. One garden remains to show how, when even slightly tended, flowers grow and flourish in the cooler air of the Villa. In former days a giant chestnut tree was the pride of this garden, only its venerable trunk now remains to tell of its departed glories; but the poyos (double walls) are full of flowers all the year, and the native Pico de paloma (Lotus Berthelotii) flourishes better here than in any other garden; it drapes the walls and half smothers the steps and stone seats with its garlands of soft grey-green, and in spring is covered with its deep red “pigeons’ beaks.” The walls are gay with stocks, carnations, verbenas, lilies, geraniums, and hosts of plants. Long hedges of Libonia floribunda, the bandera d’España of the natives, as its red and yellow blossoms represent the national colours of Spain, line the entrance, and in unconsidered damp corners white arum lilies grow, the rather despised orejas de burros, or donkeys’ ears, of the country people, who give rather apt nick-names to not only flowers, but people.

Though the higher-class Spaniards are a most exclusive race, I met with nothing but civility from their hands when asking permission to see their patio or gardens; as much cannot be said for the middle and lower classes of to-day, who are distinctly anti-foreign. The lower classes appear to regard an incessant stream of pennies as their right, and hurl abuse or stones at your head when their persistent begging is ignored, and even tradesmen are often insolent to foreigners. A spirit of independence and republicanism is very apparent. An employer of labour can obviously keep no control over his men, who work when they choose, or more often don’t work when they don’t choose, and the mother or father of a family keeps no control over the children. One day I asked our gardener why he did not send his children to school to learn to read and write, as he was deploring that he could not read the names of the seeds he was sowing. I thought it was a good moment to point a moral, but he shrugged his shoulders, and said they did not care to go, and also they had no shoes and could not go to school barefoot. The man was living rent free, earning the same wages as an average English labourer, and two sons in work contributed to the expenses of the house, besides the money he got for the crop on a small piece of land which the whole family cultivated on Sundays, and still he could not afford to provide shoes in order that his children should learn to read and write. Another man announced with pride that one of his children attended school. Knowing he had two, I inquired, “Why only one?” On which he owned that the other one used to go, but now she refused to do so, and neither he nor his wife could make her go. This independent person was aged nine!

One of the great curiosities of the Villa was the great Dragon Tree, and though it stands no more, visitors are still shown the site where it once stood and are told of its immense age. Humboldt gave the age of the tree at the time of his visit as being at least 6000 years, and though this may have been excessive, there is no doubt that it was of extreme age. It was blown down and the remains accidentally destroyed by fire in 1867, and only old engravings remain to tell of its wondrous size. The hollow trunk was large enough for a good-sized room or cave, and in the days of the Guanches, when a national assembly was summoned to create a new chief or lord, the meeting place was at the great Dragon Tree. The land on which it stood was afterwards enclosed and became the garden of the Marques de Sauzal.

The ceremony of initiating a lord was a curious one, and the Overlord of Taoro (the old name of Orotava), was the greatest of these lords, having 6000 warriors at his command. Though the dignity was inherited, it was not necessary that it should pass from father to son, and more frequently passed from brother to brother. “When they raised one to be lord they had this custom. Each lordship had a bone of the most ancient lord in their lineage wrapped in skins and guarded. The most ancient councillors were convoked to the ‘Tagoror,’ or place of assembly. After his election the king was given this bone to kiss. After having kissed it he put it over his head. Then the rest of the principal people put it over his shoulder, and he said, ‘Agoñe yacoron yñatzahaña Chacoñamet’ (I swear by the bone on this day on which you have made me great). This was the ceremony of the coronation, and on the same day the people were called that they might know whom they had for their lord. He feasted them, and there were general banquets at the cost of the new lord and his relations. Great pomp appears to have surrounded these lords, and any one meeting them in the road when they progressed to change their summer residence in the mountains to one by the sea in winter, was expected to prostrate himself on the ground, and on rising to cleanse the king’s feet with the edge of his coat of skins.” (See “The Guanches of Teneriffe,” by Sir Clement Markham.) After the conquest the Spaniards turned the temple of the Guanches into a chapel, and Mass was said within the tree.

In the Villa are several fine old churches, whose spires and domes are her fairest adornment. The principal church is the Iglesia de la Concepcion, whose domes dominate the whole town. The exterior of the church is very fine, though the interior is not so interesting. It is curious to think how the silver communion plate, said to have belonged to St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, can have come into the possession of this church. The theory that this and similar plate in the Cathedral at Las Palmas are the scattered remains of the magnificent church plate which was sold and dispersed by the order of Oliver Cromwell is generally accepted.

The fine old doorway and tower of the Convent and Church of Santo Domingo date from a time when the Spaniards had more soul for the beautiful than they have at the present time.

The narrow steep cobbled streets are hardly any of them without interest, and the old balconies, the carved shutters and glimpses of flowery patios, with a gorgeous mass of creeper tumbling over a garden wall or wreathing an old doorway, combine to make it a most picturesque town. A feature of almost every Spanish house is the little latticed hutch which covers the drip stone filter. In many an old house creepers and ferns, revelling in the dampness which exudes from the constantly wet stone, almost cover the little house, and even the stone itself grows maiden-hair or other ferns, and their presence is not regarded as interfering with the purifying properties of the stone, in which the natives place great faith. I never could believe that clean water could in any way benefit by being passed through the dirt of ages which must accumulate in these stones, there being no means of cleaning them except on the surface. The red earthenware water-pots of decidedly classical shape are made in every size, and a tiny child may be seen learning to carry a diminutive one on her head with a somewhat uncertain gait which she will soon outgrow, and in a year or two will stride along carrying a large water-pot all unconscious of her load, leaving her two hands free to carry another burden.

REALEJO ALTO

A charming walk or donkey-ride leads from the Villa along fairly level country to Realejo Alto, passing through the two little villages of La Perdoma and La Cruz Santa. In early spring the almond blossom gives a rosy tinge to many a stretch of rough uncultivated ground, and in the villages over the garden walls was wafted the heavy scent of orange blossoms. The trees at this altitude seemed freer of the deadly black blight which has ravaged all the orange groves on the lower land, and altogether the vegetation struck one as being more luxuriant and more forward. The cottage-garden walls were gay with flowers: stocks, mauve and white, the favourite alelis of the natives, long trails of geraniums and wreaths of Pico de paloma, pinks and carnations and hosts of other flowers I noticed as we rode past.

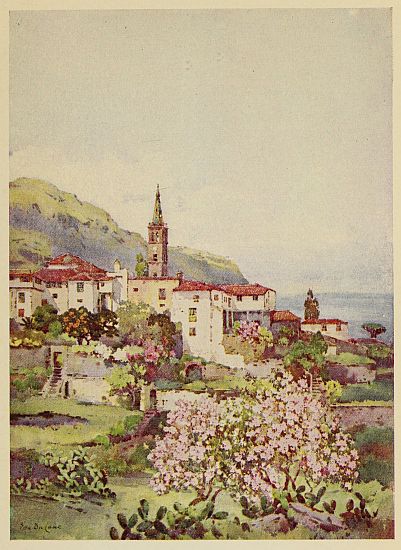

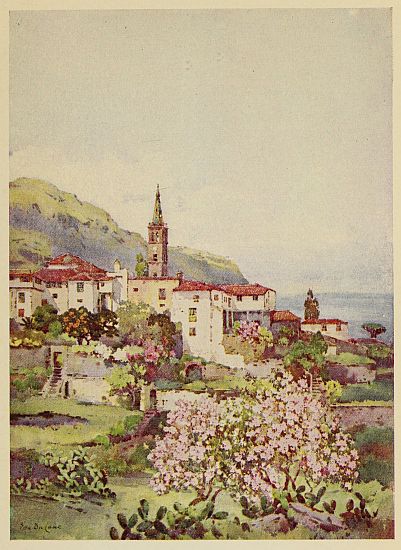

The village of Realejo Alto is, without doubt, the most picturesque village I ever saw in the Canaries. Its situation on a very steep slope with the houses seemingly piled one above the other is very suggestive of an Italian mountain village. Part of the Church of San Santiago, the portion next the tower, is supposed to be the oldest church in the island, and the spire, the most prominent feature of the village and neighbourhood, is worthy of the rest of the old church. The interior of the church is not without interest when seen in a good light, and a fine old doorway is said to be the work of Spanish workmen shortly after the conquest. The carved stone-work round this doorway and a very similar one in the lower village are unique specimens of this style of work in the islands.

The barranco which separates the upper and lower villages of Realejo was the scene of a great flood in 1820 which severely damaged both villages. Realejo Bajo, though not quite as picturesque as the upper village, is well worth a visit, and its inhabitants are justly proud of their Dragon Tree, a rival to the one at Icod which may possibly some day become as celebrated as the great tree at Orotava.

These two villages are great centres of the calado or drawn-thread-work industry. Through every open doorway may be seen women and girls bending over the frames on which the work is stretched. It is mostly of very inferior quality, very coarsely worked and on poor material, and it seems a pity that there is no supply of better and finer work. Visitors get tired of the sight of the endless stacks of bed-covers and tea-cloths which are offered to them, and certainly the work compares badly both in price and quality with that done in the East.