III

TENERIFFE (continued)

A SPELL of clear weather, late in February, made us decide to make an expedition to the Cañadas, which, except to those who are bent on mountain climbing and always wish to get to the very top of every height they see, appeals to the ordinary traveller more than ascending the Peak itself. In spite of the promise of fine weather the day before, the morning broke cloudy and at dawn, 6 A.M., we started full of doubts and misgivings as to what the sunrise would bring. We had decided to drive as far as the road would allow, as we had been warned that we should find nine or ten hours’ mule riding would be more than enough, in fact, our friends were rather Job’s comforters. Some said the expedition was so tiring that they had known people to be ill for a week after undertaking it. Others said it was never clear at the top, we must be prepared to be soaked to the skin in the mist, for the mules to stumble and probably roll head over heels, in fact that strings of disasters were certain to overtake us. Our mules were to join us at Realejo Alto, about an hour’s drive from the port, and there we determined we would decide whether we would continue, or content ourselves with a shorter expedition on a lower level.

Sunrise did not improve the prospect, a heavy bank of clouds lay over Pedro Gil, while ominous drifts of light white clouds were gathering below the Tigaia, and the prospect out to sea was not more encouraging. The mules were late, in true Spanish fashion, and we consulted a few weather-wise looking inhabitants who gathered round our carriage in the Plaza, shivering in the morning air, with their mantas or blanket cloaks wrapped closely round them. They looked pityingly at these mad foreigners who had left their beds at such an hour when they were not forced to—for the Spaniard is no early riser—and were proposing to ride up into the clouds. The optimistic members of the party said: “It is nothing but a little morning mist,” while the pessimist remarked, “Morning mists make mid-day clouds in my experience.”

The arrival of the mules put an end to further discussion. The muleteers were full of hope and confident that the clouds would disperse, or anyway that we should get above the region of cloud and find clear weather at the top, so though our old blanket-coated friend murmured “Pobrecitas” (poor things) below his breath, we made a start armed with wraps for the wet and cold we were to encounter. The clattering of the mules as we rode up the steep village street brought many heads to the windows; the little green shutters, or postijos, were hastily pushed open to enable the crowd, which appeared to inhabit every house, to catch a sight of the “Inglezes.” Inquiry as to where we were bound for, I noticed, generally brought an exclamation of “Very bad weather” (“Tiempo muy malo”), to the great indignation of our men, who muttered, “Don’t say so!”

The stony path from Realejo leads in a fairly steep ascent to Palo Blanco, a little scattered village of charcoal-burners’ huts at a height of 2200 feet. The wreaths of blue smoke from their fires mingled with the mist, but already there was a promise of better things to come, as the sun was breaking through and the clouds were thinner. The chant of the charcoal-burners is a sound one gets accustomed to in these regions, and I never quite knew whether it was merely a song which cheered them on their downward path, or whether it was to announce their approach and ask ascending travellers to move out of their way, as the size of the loads they carry on their heads makes them often very difficult to pass. Presently two stalwart girls came into sight, swinging along at a steady trot; their bare feet apparently even more at home along the stony track than the unshod feet of the mules, as there is no stopping to pick their way, on they go, only too anxious to reach their journey’s end, and drop the crushing load off their heads. We anxiously inquired as to the state of the weather higher up, and to our great relief, with no hesitation, came the answer: “Muy claro” (very clear), and in a few minutes a puff of wind blew all the mist away as if by magic, and there was a shout of triumph from the men.

Below lay the whole valley of Orotava, and we were leaving the picturesque town of the Villa Orotava far away below us on the left. The little villages of La Perdoma, La Cruz Santa, and the two Realejos, Alto and Bajo, were more immediately below us, and far away in the distance beyond the Puerto were to be seen Santa Ursula, Sauzal and the little scattered town of Tacoronte. Pedro Gil and all the range of mountains on the left had large stretches of melting snow, shining with a dazzling whiteness in the sun. It had been an unusual winter for snow, so we were assured, and it was rare to find it still lying at the end of February, but we were glad it was so, for it certainly added greatly to the beauty of the scene. At the Monte Verde, the region of green things, we called a halt, for the sake of man and beast, and while our men refreshed themselves with substantial slices of sour bread and the snow white local cheese, made from goats’ milk, and our mules enjoyed a few minutes’ breathing-space with loosened girths, we took a short walk to look down into the beautiful Barranco de la Laura. Here the trees have as yet escaped destruction at the hands of the charcoal-burners and the steep banks are still clad with various kinds of native laurel mixed with large bushes of the Erica arborea, the heath which covers all the region of the Monte Verde. The almost complete deforestation by the charcoal-burners is most deeply to be deplored, and it is sad to think how far more beautiful all this region must have been before it was stripped of its grand pine and laurel trees. The authorities took no steps to stop this wholesale destruction of the forests until it was too late, and even now, though futile regulations exist, no one takes the trouble to see that they are enforced. The law now only allows dead wood to be collected, but it is easy enough to make dead wood—a man goes up and breaks down branches of trees or retama, and a few weeks later goes round and collects them as dead wood, and so the law is evaded. As there is a never-ending demand for charcoal, it being the only fuel the Spaniard uses, so matters will continue until there is nothing left to cut.

No doubt we were on the same path as that by which Humboldt had travelled when he visited Teneriffe in 1799 and ascended the Peak. His description of the vegetation shows how the ruthless axe of the charcoal-burners has destroyed some of the most beautiful forests in the world. Humboldt had been obliged to abandon his travels in Italy in 1795 without visiting the volcanic districts of Naples and Sicily, a knowledge of which was indispensable for his geological studies. Four years later the Spanish Court had given him a splendid welcome and placed at his disposal the frigate Pizarro for his voyage to the equinoctial regions of New Spain. After a narrow escape of falling into the hands of English privateers the Trade winds blew him to the Canaries. The 21st day of June, 1799, finds him on his way to the summit of the Peak accompanied by his friend Bonpland, M. le Gros, the secretary of the French Consulate in Santa Cruz, and the English gardener of Durasno (the botanical gardens of Orotava). The day appears not to have been happily chosen. The top of the Peak was covered in thick clouds from sunrise up to ten o’clock. Only one path leads from Villa Orotava through the retama plains and the mal pays. “This is the way that all visitors must follow who are only a short time in Teneriffe. When people go up the Peak” (these are Humboldt’s words) “it is the same as when the Chamounix or Etna are visited, people must follow the guides and one only succeeds in seeing what other travellers have seen and described.” Like others he was much struck by the contrast of the vegetation in these parts of Teneriffe and in that surrounding Santa Cruz, where he had landed. “A narrow stony path leads through Chestnut woods to regions full of Laurel and Heath, and then further to the Dornajito springs; this being the only fountain that is met with all the way to the Peak. We stopped to take our provision of water under a solitary fir tree. This station is known in the country by the name of Pino del Dornajito. Above this region of arborescent heaths called Monte Verde, is the region of ferns. Nowhere in the temperate zones have I seen such an abundance of the Pteris, Blechium and Asplenium; yet none of these plants have the stateliness of the arborescent ferns which, at the height of 500 and 600 toises, form the principal ornaments of equinoctial America. The root of the Pteris aquilina serves the inhabitants of Palma and Gomera for food. They grind it to powder, and mix it with a quantity of barley meal. This composition when boiled is called gofio; the use of so homely an aliment is proof of the extreme poverty of the lower classes of people in the Canary Islands. (Gofio is still largely consumed).

“The region of ferns is succeeded by a wood of juniper trees and firs, which has suffered greatly from the violence of hurricanes (not one is now left). In this place, mentioned by some travellers under the name of Caraveles, Mr. Eden states that in the year 1705, he saw little flames, which according to the doctrines of the naturalists of his time, he attributes to sulphurous exhalations igniting spontaneously. We continued to ascend, till we came to the rock of La Gayta and to the Portillo: traversing this narrow pass between two basaltic hills, we entered the great plain of Spartium.... We spent two hours in crossing the Llano del Retama, which appears like an immense sea of white sand. In the midst of the plain are tufts of the retama, which is the Spartium nubigenum of Aiton. M. de Martinière wished to introduce this beautiful shrub into Languedoc, where firewood is very scarce. It grows to a height of 9 ft. and is loaded with odoriferous flowers, with which the goat-hunters who met in our road had decorated their hats. The goats of the Peak, which are of a dark brown colour, are reckoned delicious food; they browse on the spartium and have run wild in the deserts from time immemorial.” Spending the night on the mountain, though in mid summer, the travellers complained bitterly of the cold, having neither tents nor rugs. At 3 A.M. they started by torch-light to make the final ascent to the summit of the Piton. “A strong northerly wind chased the clouds, the moon at intervals shooting through the vapours exposed its disk on a firmament of the darkest blues, and the view of the volcano threw a majestic character over the nocturnal scenery.

“Sometimes the peak was entirely hidden from our eyes by the fog, at other times it broke upon us in terrific proximity: and like an enormous pyramid, threw its shadow over the clouds rolling at our feet.”

Scaling the mountain on the north-eastern side, in two hours the party reached Alta Vista, following the same course as travellers of to-day, passing over the mal pays (a region devoid of vegetable mould and covered with fragments of lava) and visiting the ice caves. After the Laurels follow ferns of great size, Junipers and Pines (not one is now left of either) all the way up to the Portillo.

The Portillo was still towering far above us, the gateway of the range, as its name implies, through which we had to pass to get to the Cañadas, and the stony path, though a well defined one, meanders on, not at a very steep incline, past rough hillocks where here and there pumice stone appears. Gradually the heath, which was just coming into flower, and in a few weeks would be covered with its rather insignificant little white or pinkish blossoms, becomes interspersed with codeso, Adenocarpus viscosus, with its peculiar flat spreading growth and tiny leaves of a soft bluish-green. During all the long ascent there is no sign of the Peak; the path lies so immediately beneath the dividing range that it is not until the Portillo itself is reached, that it suddenly bursts into view. It is a grand scene which lies before one. The foreground of rocky ground is interspersed with great bushes of retama (Sparto-cytisus nubigens), a species of broom said to be peculiar to this district. In growth it somewhat resembles Spartium junceum, commonly known in England as Spanish broom, but is more stubby and perhaps not so graceful. When in flower in May its sweet scent is so powerful that not only does it fill the whole air in this mountain district, but sailors are said to smell it miles out at sea. Our guides told us some bushes had white flowers and others white tinged with rose colour. At this season large patches of thawing snow take the place of flowers, but the bushes of retama can be seen piercing the Peak’s dense mantle of snow up to a height of quite 10,000 feet.

I had been told that all the beauty of the Peak was lost when seen from so near, that the beautiful pyramid of rock and snow which rises some 12,000 feet and stands towering above the valley of Orotava would look like a mere hill when seen rising from the moat of fine sand, which is what the Cañadas most resemble, that in fact, all enchantment would be gone. One writer even has gone so far as to call the Peak an ugly cinder-heap when seen from the Cañadas on the other side, and to say they found themselves “in a lifeless, soundless world, burnt out, dead, the very abomination of desolation, where once raged a fiery inferno over a lake of boiling lava.” I cannot help thinking that the writer of the above must have been travelling under adverse circumstances; it is curious how being overtired, wet and cold will make one find no beauty in a scene, which others, who like ourselves have seen it in glorious sunshine, will describe as one of the most beautiful sights in the world.

The path just beyond the Portillo (7150 ft.) divides, and those who propose to ascend the Peak follow the track up the side of the Montaña Blanca, a snow-clad hump at the east base of the Peak. The cone itself is locally called Lomo Tiezo, and rises at an angle of 28°. The stone hut at the Alta Vista (10,702 ft.) is where many a weary traveller spends the night, before ascending the final 1400 ft. on foot, as the mules are left at the hut. No doubt in clear weather the traveller is well repaid, and the scene is well described as follows by Mr. Samler Brown: “Those who cannot ascend the mountain would probably greatly help their imagination by looking at a lunar crater through a telescope. The surroundings are the essence of desolation and ruin. On one side the rounded summit of the Montaña Blanca, on the other the threatening craters of the Pico Viejo and of Chahorra, the latter three-quarters of a mile in diameter, 10,500 ft. high, once a boiling cauldron and even now ready to burst into furious life at any moment. Below, the once circular basin of the Cañadas, seamed with streams of lava and surrounded by its jagged and many-coloured walls. Around, a number of volcanoes, standing, as Piazzi Smyth says, like fish on their tails with widely gaping mouths. On the upper slopes the pine forests and far beneath the sea, with the Six Satellites (the islands of La Palma, Gomera, Hierro, Grand Canary, Fuerteventura and Lanzarote) floating in the distance, the enormous horizon giving the impression that the looker-on is in a sort of well rather than on a height which, taken in relation to its surroundings is second to none in the world.”

To attain the rude little shrine at the Fortaleza where a rest was to be taken, the path leads down into the Cañadas itself. A stretch of fine yellow sand, like the sand of the Sahara, thoroughly sun-baked, proved too great a temptation to one of the mules, and regardless of its rider and luncheon-basket, it enjoyed a good roll in the soft warm bed—luckily with no untoward results. After a welcome rest in the grateful shade of a retama bush, we turned our backs to the Peak and left this beautiful solitary scene. The island of La Palma seemed to be floating in the sky; the line of the horizon dividing sea and sky appeared to be all out of place, in fact it seems to be a weird uncanny world in these parts, and though to-day the Peak may be standing calm and serene, bathed in sunshine and clad in snow, still it reminds one of the death and destruction it has caused by fire and flood, and who knows when it may some day awake from its long sleep and shake the whole island to its foundations.

It is an accepted theory that the Cañadas themselves were originally an immense crater, the second largest in the world, and during a period of activity they threw up the Peak which became the new crater. Probably during this process the Cañadas themselves subsided, and left the wall of rock which appears to form a perfect protection to the Valley of Orotava in case the Peak should some day again spout forth burning lava.

It was in the early winter of 1909 that the inhabitants of Teneriffe were reminded that their volcano was not dead. For nearly a year previously frequent slight shocks of earthquake had warned geological experts that some upheaval was to be expected, which in November were followed by loud detonations, each one shaking the houses in Orotava. One of the inhabitants has described the sensation as one of curious instability, that the houses felt as though they were built on a foundation of jelly. An entirely new crater opened twenty miles from the Peak, and though so far distant from Orotava, the flashes of light were distinctly visible above the lower mountains on the south side of the Peak. Very little damage seems to have been done, as luckily there were no villages near enough to be annihilated by the streams of lava, but most exaggerated reports of the eruptions were circulated in Europe, and it is even said that a message was sent to the Spanish Government asking for men-of-war to be sent at once to take away the inhabitants as the island was sinking into the sea! Many geological authorities have given it as their opinion that it is most unlikely that there will be another eruption in less than another hundred years, which is consoling and reassuring.

As the paths were dry we were able to return by a different route, which though rather longer is far more beautiful, and to those who prefer walking to riding downhill is highly to be recommended. The mules appear to be more sure-footed in the stony paths and once the region of the Monte Verde begins again and the path is smooth their unshod feet get no hold, and in wet weather the path is a mere “mud slide” and should not be attempted. It was a beautiful walk along the crest of the range; the Peak was lost to sight but the valley below lay filled with drifting patches of light mist, through which could just be seen the Villa bathed in the afternoon light, and above, all was clear. Pedro Gil, and the Montaña Blanca beyond, glowed in a red light, and right away in the distance the mountains round La Laguna were just visible.

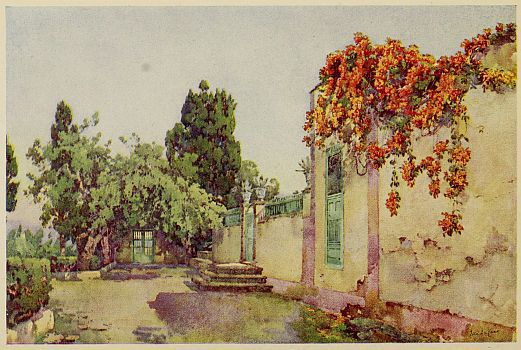

ENTRANCE TO A SPANISH VILLA

From La Corona the view is perhaps at its best. On the left the pine woods above Icod de los Vinos stretch away into the distance to the extreme west of the island, and on the right the valley of Orotava lies spread out like a map. Just below La Corona one gets back into cultivated regions and the sight of a country-woman with the usual burden on her head reminded us how many hours it was since we had seen a sign of life—not, indeed, since we had passed the two charcoal-burners in the early morning who had given such welcome news of clear weather ahead. Icod el Alto, with the roughest village street it has ever been my fate to encounter, was soon left behind, and the mules trudged wearily down as steep a path as we had met with anywhere, to Realejo Bajo and back to civilisation and the prosaic. A rickety little victoria with three lean but gallant little horses took us home exactly twelve hours from the time we started. We had not meant to break records, and on the homeward path had certainly taken things easily—the ride from Realejo Alto to the Cañadas was exactly four hours, one hour’s rest, five hours’ ride down, partly walking, and two hours’ driving—and we were neither wet through nor so tired that we were ill for a week. I had heard a good description of mule riding by some one who was consulted as to whether it was very tiring, and his answer was, “It is not riding, you just sit, and leave the rest to the mule and Providence!”