I

I cannot remember the time when I was not absolutely certain that I would be a millionaire. And I had not been a week in the big wholesale dry-goods house in Worth Street in which I made my New York start, before I looked round and said to myself: “I shall be sole proprietor here some day.”

Probably clerks dream the same thing every day in every establishment on earth—but I didn’t dream; I knew. From earliest boyhood I had seen that the millionaire was the only citizen universally envied, honoured, and looked up to. I wanted to be in the first class, and I knew I had only to stick to my ambition and to think of nothing else and to let nothing stand in the way of it. There are so few men capable of forming a definite, serious purpose, and of persisting in it, that those who are find the road almost empty before they have gone far.

By the time I was thirty-three years old I had arrived at the place where the crowd is pretty well thinned out. I was what is called a successful man. I was general manager of the dry-goods house at ten thousand a year—a huge salary for those days. I had nearly sixty thousand dollars put by in gilt-edged securities. I had built a valuable reputation for knowing my business and keeping my word. I owned a twenty-five-foot brownstone house in a side street not far from Madison Avenue, and in it I had a comfortable, happy, old-fashioned home. At thirty-two I had gone back to my native town to marry a girl there, one of those women who have ambition beyond gadding all the time and spending every cent their husbands earn, and who know how to make home attractive to husband and children.

I couldn’t exaggerate the value of my family, especially my wife, to me in those early days. True, I should have gone just as far without them, but they made my life cheerful and comfortable; and, now that sentiment of that narrow kind is all in the past, it’s most agreeable occasionally to look back on those days and sentimentalise a little.

That I worked intelligently, as well as hard, is shown by the fact that I was made junior partner at thirty-eight. My partner—there were only two of us—was then an elderly man and the head of the old and prominent New York family of Judson—that is not the real name, of course. Ours was the typical old-fashioned firm, doing business on principles of politeness rather than of strict business. One of its iron-clad customs was that the senior partner should retire at sixty. Mr. Judson’s intention was to retire in about five years, I to become the head of the firm, though with the smaller interest, and one of his grandsons to become the larger partner, though with the lesser control—at least, for a term of years.

It was called evidence of great friendship and confidence that Mr. Judson thus “favoured” me. Probably this notion would have been stronger had it been known on what moderate terms and at what an easy price he let me have the fourth interest. No doubt Mr. Judson himself thought he was most generous. But I knew better. There was no sentimentality about my ideas of business, and my experience has been that there isn’t about any one’s when you cut through surface courtesy and cant and get down to the real facts. I knew I had earned every step of my promotion from a clerk; and, while Mr. Judson might have selected some one else as a partner, he wouldn’t have done so, because he needed me. I had seen to that in my sixteen years of service there.

Judson wasn’t a self-made man, as I was. He had inherited his share in the business, and a considerable fortune, besides. The reason he was so anxious to have me as a partner was that for six years I had carried all his business cares, even his private affairs. Yes, he needed me—though, no doubt, in a sense, he was my friend. Who wouldn’t have been my friend under the circumstances? But, having looked out for his own interest and comfort in selecting me, why should he have expected that I wouldn’t look out for mine? The only kind of loyalty a man who wishes to do something in the world should give or expect is the mutual loyalty of common interest.

I confess I never liked Judson. To be quite frank, from the first day I came into that house, I envied him. I used to think it was contempt; but, since my own position has changed, I know it was envy. I remember that the first time I saw him I noted his handsome, carefully dressed figure, so out of place among the sweat and shirt sleeves and the litter of goods and packing cases, and I asked one of my fellow-clerks: “Who’s that fop?” When he told me it was the son of the proprietor, and my prospective chief boss, I said to myself: “It won’t be hard to get you out of the way;” for I had brought from the country the prejudice that fine clothes and fine manners proclaim the noddle-pate.

I envied my friend—for, in a master-and-servant way, that was highly, though, of course, secretly distasteful to me, we became friends. I envied him his education, his inherited wealth, his manners, his aristocratic appearance, and, finally, his social position. It seemed to me that none of these things that he had and I hadn’t belonged of right to him, because he hadn’t earned them. It seemed to me that his having them was an outrageous injustice to me.

I think I must have hated him. Yes, I did hate him. How is it possible for a man who feels that he is born to rule not to hate those whom blind fate has put as obstacles in his way? To get what you want in this world you must be a good hater. The best haters make the best grabbers, and this is a world of grab, not of “By your leave,” or “If you’ll permit me, sir.” You can’t get what you want away from the man who’s got it unless you hate him. Gentle feelings paralyse the conquering arm.

So, at thirty-eight, it seemed to be settled that I was to be a respectable Worth Street merchant, in active life until I should be sixty, always under the shadow of the great Judson family, and thereafter a respectable retired merchant and substantial citizen with five hundred thousand dollars or thereabouts. But it never entered my head to submit to that sort of decree of destiny, dooming me to respectable obscurity. Nature intended me for larger things.

The key to my true destiny, as I had seen for several years, was the possession of a large sum of money—a million dollars. Without it, I must work on at my past intolerably slow pace. With it, I could leap at once into my kingdom. But, how get it? In the regular course of any business conducted on proper lines, such a sum, even to-day, rewards the successful man starting from nothing only when the vigour of youth is gone and the habits of conservatism and routine are fixed. I knew I must get my million not in driblets, not after years of toil, but at once, in a lump sum. I must get it even at some temporary sacrifice of principle, if necessary.

If I had not seen the opportunity to get it through Judson and Company, I should have retired from that house years before I got the partnership. But I did see it there, saw it coming even before I was general manager, saw it the first time I got a peep into the private affairs of Mr. Judson.

Judson and Company, like all old-established houses, was honeycombed with carelessness and wastefulness. To begin with, it treated its employees on a basis of mixed business and benevolence, and that is always bad unless the benevolence is merely an ingenious pretext for getting out of your people work that you don’t pay for. But Mr. Judson, having a good deal of the highfaluting grand seigneur about him, made the benevolence genuine. Then, the theory was that the Judsons were born merchants, and knew all there was to be known, and did not need to attend to business. Mr. Judson, being firmly convinced of his greatness, and being much engaged socially and in posing as a great merchant at luncheons and receptions to distinguished strangers and the like, put me in full control as soon as he made me general manager. He interfered in the business only occasionally, and then merely to show how large and generous he was—to raise salaries, to extend unwise credits, to bolster up decaying mills that had long sold goods to the house, to indorse for his friends. Friends! Who that can and will lend and indorse has not hosts of friends? What I have waited to see before selecting my friends is the friendship that survives the death of its hope of favours—and I’m still waiting.

As soon as I became partner I confirmed in detail the suspicion, or, rather, the instinctive knowledge, which had kept me from looking elsewhere for my opportunity.

I recall distinctly the day my crisis came. It had two principal events.

The first was my discovery that Mr. Judson had got the firm and himself so entangled that he was in my power. I confess my impulse was to take a course which a weaker or less courageous man would have taken—away from the course of the strong man with the higher ambition and the broader view of life and morals. And it was while I seemed to be wavering—I say “seemed to be” because I do not think a strong, far-sighted man of resolute purpose is ever “squeamish,” as they call it—while, I say, I was in the mood of uncertainty which often precedes energetic action, we, my wife and I, went to dinner at the Judsons.

That dinner was the second event of my crucial day. Judson’s family and mine did not move in the same social circle. When people asked my wife if she knew Mrs. Judson—which they often maliciously did—she always answered: “Oh, no—my husband keeps our home life and his business distinct; and, you know, New York is very large. The Judsons and we haven’t the same friends.” That was her way of hiding our rankling wound—for it rankled with me as much as with her; in those days we had everything in common, like the humble people that we were.

I can see now her expression of elation as she displayed the note of invitation from Mrs. Judson: “It would give us great pleasure if you and your husband would dine with us quite informally,” etc. Her face clouded as she repeated, “quite informally.” “They wouldn’t for worlds have any of their fashionable friends there to meet US.” Even then she was far away from the time when, to my saying, “You shall have your victoria and drive in the park and get your name in the papers like Mrs. Judson,” she laughed and answered—honestly, I know—“We mustn’t get to be like these New Yorkers. Our happiness lies right here with ourselves and our children. I’ll be satisfied if we bring them up to be honest, useful men and women.” That’s the way a woman should talk and feel. When they get the ideas that are fit only for men everything goes to pot.

But to return to the Judson dinner—my wife and I had never before been in so grand a house. It was, indeed, a grand house for those days, though it wouldn’t compare with my palace overlooking the park, and would hardly rank to-day as a second-rate New York house. We tried to seem at our ease, and I think my wife succeeded; but it seemed to me that Judson and his wife were seeing into my embarrassment and were enjoying it as evidence of their superiority. I may have wronged him. Possibly I was seeking more reasons to hate him in order the better to justify myself for what I was about to do. But that isn’t important.

My wife and I were as if in a dream or a daze. A whole, new world was opening to both of us—the world of fashion, luxury, and display. True, we had seen it from the outside before; and had had it constantly before our eyes; but now we were touching it, tasting it, smelling it—were almost grasping it. We were unhappy as we drove home in our ill-smelling public cab, and when we reentered our little world it seemed humble and narrow and mean—a ridiculous fool’s paradise.

We did not have our customary before-going-to-sleep talk that night, about my business, about our investments, about the household, about the children—we had two, the boys, then. We lay side by side, silent and depressed. I heard her sigh several times, but I did not ask her why—I understood. Finally I said to her: “Minnie, how’d you like to live like the Judsons? You know we can afford to spread out a good deal. Things have been coming our way for twelve years, and soon——”

She sighed again. “I don’t know whether I’m fitted for it,” she said; “I think all those grand things would frighten me. I’d make a fool of myself.”

It amuses me to recall how simple she was. Who would ever suspect her of having been so, as she presides over our great establishments in town and in the country as if she were born to it? “Nonsense!” I answered. “You’d soon get used to it. You’re young yet, and a thousand times better looking than fat old Mrs. Judson. You’ll learn in no time. You’ll go up with me.”

“I don’t think they’re as happy as we are,” she said. “I ought to be ashamed of myself to be so envious and ungrateful.” But she sighed again.

I think she soon went to sleep. I lay awake hour after hour, a confusion of thoughts in my mind—we worry a great deal over nice points in morals when we are young. Then, suddenly, as it seemed to me, the command of destiny came—“You can be sole master, in name as well as in fact. You are that business. He has no right there. Put him out! He is only a drag, and will soon ruin everything. It is best for him—and you must!”

I tossed and turned. I said to myself, “No! No!” But I knew what I would do. I was not the man to toil for years for an object and then let weakness cheat me out of it. I knew I would make short shrift of a flabby and dangerous and short-sighted generosity when the time came.

One morning, about six months later, Mr. Judson came to me as I was busy at my desk and laid down a note for five hundred thousand dollars, signed by himself. “It’ll be all right for me to indorse the firm’s name upon that, won’t it?” he said, in a careless tone, holding to a corner of the note, as if he were assuming that I would say “Yes,” and he could then take it away.

A thrill of delight ran through me at this stretch of the hand of my opportunity for which I had been planning for years, and for which I had been waiting in readiness for nearly three months. I looked steadily at the note. “I don’t know,” I said, slowly, raising my eyes to his. His eyes shifted and a hurt expression came into them, as if he, not I, were refusing. “I’m busy just now. Leave it, won’t you? I’ll look at it presently.”

“Oh, certainly,” he said, in a surprised, shy voice. I did not look up at him again, but I saw that his hand—a narrow, smooth hand, not at all like mine—was trembling as he drew it away.

We did not speak again until late in the afternoon. Then I had to go to him about some other matter, and, as I was turning away, he said, timidly: “Oh, about that note——”

“It can’t be indorsed by the firm,” I said, abruptly.

There was a long silence between us. I felt that he was inwardly resenting what he must be calling the insolence of the “upstart” he had “created.” I was hating him for the contemptuous thoughts that seemed to me to be burning through the silence from his brain to mine, was hating him for putting me in a false position even before myself with his plausible appearance of being a generous gentleman—I abhor the idea of “gentleman” in business; it upsets everything, at once.

When he did speak, he only said: “Why not?”

I went to my desk and brought a sheet of paper filled with figures. “I have made this up since you spoke to me this morning,” I said, laying it before him.

That was false—a trifling falsehood to prevent him from misunderstanding my conduct in making a long and quiet investigation. The truth is that that crucial paper was the work of a great many days, and not a few nights, of thought and labour—it was my cast for my million.

The paper seemed to show at a glance that the firm was practically ruined, and that Mr. Judson himself was insolvent. It was to a certain extent an over-statement, or, rather, a sort of anticipation of conditions that would come to pass within a year or two if Mr. Judson were permitted to hold to his course. While in a sense I took advantage of his ignorance of our business and his own, and also of his lack of familiarity with all commercial matters, yet, on the other hand, it was not sensible that I should tide him over and carry him, and it was vitally necessary that I should get my million. Had he been shrewder, I should have got it anyhow, only I should have been compelled to use methods that, perhaps, would have seemed less merciful.

I sat beside him as he read; and, while I pitied him, for I am human, after all, I felt more strongly a sense of triumph, that I, the poor, the obscure, by sheer force of intellect, had raised myself up to where I had my foot upon the neck of this proud man, ranking so high among New York’s distinguished merchants and citizens. I have had many a triumph since, and over men far superior to Judson; but I do not think that I have ever so keenly enjoyed any other victory as this, my first and most important.

Still, I pitied him as he read, with face growing older and older, and, with his pride shot through the vitals, quivering in its death agony. I said, gently, when he had finished and had buried his face in his hands: “Now, do you understand, Mr. Judson, why I won’t sign away my commercial honour and my children’s bread?”

He shrank and shivered, as if, instead of having spoken kindly to him, I had struck him. “Spare me!” he said, brokenly. “For God’s sake, spare me!” and, after a moment, he groaned and exclaimed: “and I—I—have ruined this house, established by my grandfather and held in honour for half a century!” A longer pause, then he lifted his haggard face—he looked seventy rather than fifty-five; his eyeballs were sunk in deep, blue-black sockets; his whole expression was an awful warning of the consequences of recklessness in business. I have never forgotten it. “I trust you,” he said; “what shall I do?”

He placed himself entirely in my hands; or, rather, he left his affairs where they had been, except when he was muddling them, for more than six years. I dealt generously by him, for I bought him out by the use of my excellent personal credit, and left him a small fortune in such shape that he could easily manage it. He was free of all business cares; I had taken upon my shoulders not only the responsibilities of that great business, but also a load of debt which would have staggered and frightened a man of less courageous judgment.

I did not see him when the last papers were signed—he was ill and they were sent to his house. Two or three weeks later I heard that he was convalescent and went to see him. Now that he was no longer in my way, and that the debt of gratitude was transferred from me to him, I had only the kindliest, friendliest feelings for him. Those few weeks had made a great change in me. I had grown, I had come into my own, I realised how high I was above the mass of my fellow-men, and I was insisting upon and was receiving the respect that was my due. My sensations, as I entered the Judson house, were vastly different from what they were when the pompous butler admitted me on the occasion of the one previous visit, and I could see that he felt strongly the alteration in my station. I felt generous pity as I went into the library and looked down at the broken old failure huddled in a big chair. What an unlovely thing is failure, especially grey-haired failure! I said to myself: “How fortunate for him that this helpless creature fell into my hands instead of into the hands of some rascal or some cruel and vindictive man!” I was about to speak, but something in his steady gaze restrained me.

“I have admitted you,” he said, in a surprisingly steady voice, when he had looked me through and through, “because I wish you to hear from me that I know the truth. My son-in-law returned from Europe last week, and, learning what changes had been made, went over all the papers.”

He looked as if he expected me to flinch. But I did not. Was not my conscience clear?

“I know how basely you have betrayed me,” he went on. “I thank you for not taking everything. I confess your generosity puzzles me. However, you have done nothing for which the law can touch you. What you have stolen is securely yours. I wish you joy of it.”

My temper is not of the sweetest—dealing with the trickeries and stupidities of little men soon exhausts the patience of a man who has much to do in the world, and knows how it should be done. But never before or since have I been so insanely angry. I burst into a torrent of abuse. He rang the bell; and, when the servant came, calm and clear above my raging rose his voice, saying, “Robert, show this person to the door.” For the moment my mind seemed paralysed. I left, probably looking as base and guilty as he with his wounded vanity and his sufferings from the loss of all he had thrown away imagined me to be.

I confess that that was a very bad quarter of an hour. But, to make a large success in this world, and in the brief span of a lifetime, one must submit to discomforts of that kind occasionally. There are compensating hours. I had one last week when I attended the dedication of the splendid two-million-dollar recitation hall I have given to —— University.

Not until I was several blocks from Judson’s did the sense of my wrongs sting me into rage again. I remember that I said: “Infamous ingratitude! I save this fine gentleman from bankruptcy, and my reward is that he calls me a thief—me, a millionaire!”

Millionaire! In that word there was a magic balm for all the wounds to my pride and my then supersensitive conscience—a justification of the past, a guarantee of the future.

With my million safely achieved, I looked about me as a conqueror looks upon the conquered. A thousand dollars saved is the first step toward a competence; a million dollars achieved is the first step toward a Crœsus; and, in matters of money, as in everything else, “it is the first step that counts,” as the French say. I was filled with the passion for more, more, more. I felt myself, in imagination, growing mightier and mightier, lifting myself higher and more dazzlingly above the dull mass of work-a-day people with their routines of petty concerns.

In the days of our modesty my wife used to plan that we would retire when we had twenty thousand a year—enough, she then thought, to provide for every want, reasonable or unreasonable, that we and the children could have. Now, she would have scorned the idea of retiring as contemptuously as I would. She was eager to do her part in the process of expansion and aggrandisement, was eager to see us socially established, to put our children in the position to make advantageous marriages. We would be outshone in New York by none!

To win a million is to taste blood. The million-mania—for, in a sense, I’ll admit it is a mania—is roused and put upon the scent, and it never sleeps again, nor is its appetite ever satisfied or even made less ravenous.

A few years, and I left dry-goods for finance, where the pursuit of my passion was more direct and more rapidly successful. Every day I fixed my thoughts upon another million; and, as all who know anything about the million-mania will tell you, the act of fixing the thought upon a million, when one has earned the right to acquire millions, makes that million yours, makes all who stand between you and it aggressors to be clawed down and torn to pieces. As I grew my rights were respected more and more deferentially. Men now bow before me. They understand that I can administer great wealth to the best advantage, that I belong to one of that small class of beings created to possess the earth and to command the improvident and idealess inhabitants thereof how and where and when to work.

My family?

I confess they have not risen to my level or to the opportunities I have made for them. Naturally, with great wealth, the old simple family relationship was broken up. That was to be expected—the duties of people in our position do not permit indulgence in the simple emotions and pastimes of the family life of the masses. But neither, on the other hand, was it necessary that my wife should become a cold and calculating social figure, full of vanity and superciliousness, instead of maintaining the proud dignity of her position as my wife. Nor was it necessary that my children should become selfish, heartless, pleasure-seekers, caring nothing for me except as a source of money.

I suppose I am in part responsible—my great enterprises have left me little time for the small details of life, such as the training of children. They were admirably educated, too. I provided the best governesses and masters, and saw to it that they learned all that a lady or a gentleman should know; and in respect of dress and manners I admit that they do very well, indeed. Possibly, the complete breaking up of the family, except as it is held together by my money, is due to the fact that we see so little of one another, each having his or her separate establishment. Possibly I am a little old-fashioned, a little too exacting, in my idea of wife and children. Certainly they are aristocratic enough.

My son James is the thorn in my side. And, whenever I have a moment’s rest from my affairs, I find myself thinking of him, worrying over him. The latest development in his character is certainly disquieting.

He was twenty-five years old yesterday. He was educated at our most aristocratic university here, and at one in Europe of the same kind. It was his mother’s dream that he should be “brought up as a gentleman”; and that fell in with my ideas, for I did not wish him to be a money-maker, but the head of the family I purposed to found upon my millions, which are already numerous enough to secure it for many generations. “There is no call for him to struggle and toil as I have,” I said to myself. “The sort of financial ability I possess is born in a man and can’t be taught or transmitted by birth. He would make a small showing, at best, as a business man. As a gentleman he will shine. He only needs just enough business training to enable him to supervise those who will take care of his fortune and that of the rich woman he will marry.” I was determined that he should marry in his own class—and, indeed, he is not a sentimentalist, and, therefore, is not likely to disregard my wishes in that matter.

When he was eighteen I caught him in a fashionable gambling-house one night when I thought he was at his college. I could not but admire the coolness with which he made the best of it: stood beside me as I sat playing faro, then went over to a roulette table and lost several hundred dollars on a few spins of the ball. But the next day I took him sharply to task—it was one thing for me to play, at my age and with my fortune, I explained, but not the same for him, at his age, and with nothing but an allowance.

He shrugged his shoulders indifferently. “Really, governor,” he said, “a man must do as the other fellows in his set do. Didn’t you see whom I was with? If you wish me to travel with those people I must go their gait.”

That was not unreasonable, so I dismissed him with a cautioning. At twenty he went abroad, and, a year after he had returned, his bills and drafts were still coming. I sent for him. “Why don’t you pay your debts, sir?” I demanded, angrily, for such conduct was directly contrary to my teaching and example.

He gave me his grandest look—he is a handsome, aristocratic-looking fellow, away ahead of what Judson must have been at his age. “But, my dear governor,” he said, “a gentleman pays his debts when he feels like it.”

“No, he don’t,” I answered, furiously, for my instinct of commercial promptness was roused. “A scoundrel pays his debts when he feels like it. A gentleman pays ’em when they’re due.”

His reply was a smile of approval, and “Excellent! The best epigram I’ve heard since I left Paris. You’re as great a genius at making phrases as you are at making money.”

I caught him speculating in Wall Street—“One must amuse one’s self,” he said, cheerfully. But I was not to be put off this time. I had had some reports on his life—many wild escapades, many fantastic extravagances. The terrible downfall of two young men of his set made me feel that the time for discipline was at hand. But, as I was very busy, I had only time to read him a brief lecture on speculation and to exact from him a promise that he would keep out of Wall Street. He gave the promise so reluctantly that I felt confident he meant to keep it.

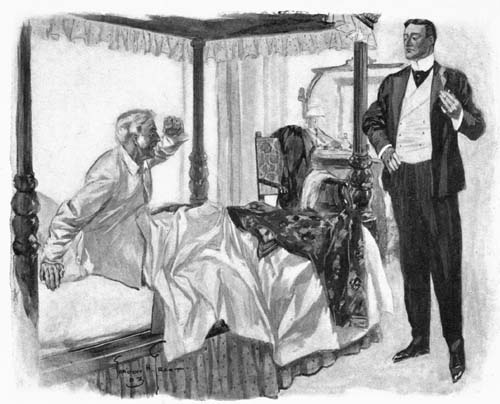

A week ago yesterday morning he came into my bedroom, before I was up, and said to my valet, Pigott: “Just take yourself off, Piggy!” And, when we were alone, he began: “Mother said I was to come straight to you.”

“What is it?” I demanded, my anger rising—experience has taught me that the more offhand his manner, the more serious the offence I should have to repair.

“I broke my promise to you about speculating, sir,” he replied, much as if he were apologising for having jostled me in a crowd.

I sat up in bed, feeling as if I were afire. “And does a gentleman keep his promises only when he feels like it?” I asked.

“But that isn’t all,” he went on. “My pool’s gone smash—you were on the other side and I never suspected it. And I’ve got a million to pay, besides——”

He took out his cigarette case, and lighted a cigarette with great deliberation.

“Besides—what?” I said, wishing to know all before I began upon him.

“I wrote your name across the back of a bit of paper,” he answered, hiding his face in a big cloud of smoke.

I fell back in the bed, feeling as if I had been struck on the head with a heavy weight. “You scoundrel!” I gasped.

“Sour grapes,” he muttered, his cheeks aflame and his eyes blazing at me.

“‘Don’t get apoplectic,’ he said, calmly; ‘you know you stole your start.’”

“What do you mean?” I said, my mind in confusion.

“The fathers have eaten sour grapes,” he quoted, “and the children’s teeth are set on edge.”

I half sprang from the bed at this insolence. “Don’t get apoplectic,” he said, calmly; “you know you stole your start.?