II

About a month after I sent James to my place on Long Island to be in the custody of his mother, I was dining in my Fifth Avenue house with only Burridge, my secretary, and Jack Ridley, who calls himself my “court fool.”

Although my mind was crowded with large affairs involving great properties and millions of capital, hardly a day had passed without my thinking of James and of his infamous conduct toward me. But without neglecting the duties which my position as a financial leader impose upon me, it was impossible for me to take time to do my duty as a parent. The duty which particularly pressed and absolutely prevented me from attending to my son was that of overcoming difficulties I had encountered in consolidating the three railways which I control in the State. To achieve my purpose it was necessary that a somewhat radical change be made in a certain law. I sent my agent to Boss —— to arrange the matter. I learned that he refused to order the change unless I would pay him three hundred thousand dollars in cash and would give him the opportunity to buy to a like amount of the new stock at par. He pleaded that the change would cause a tremendous outcry if it were discovered, as it almost certainly would be, and that he must be in a position to provide a correspondingly large campaign fund to “carry the party” successfully through the next campaign. He said his past favours to me had brought him to the verge of political ruin. In a sentence, the miserable old blackmailer was trying to drive as hard a bargain with me as if I had not been making stiff contributions to what he calls his “campaign fund” for years with only trifling favours in return. I was willing to pay what the change was worth, but I would not be bled. I brought pressure to bear from the national organisation of his party, and he came round—apparently.

Just as my bill was slipping quietly through the State Senate, having passed the Lower House unobserved, the other boss raised a terrific hullabaloo. Boss —— denied to my people that he had “tipped off” what was doing in order to revenge himself and get his blood-money in another way; but I knew at once that the sanctimonious old thief had outwitted me.

It looked as if I would have to yield. Of course I should have done so in the last straits, for only a fool holds out for a principle when holding out means no gain and a senseless and costly loss. But the knowledge that a defeat would cost me dear in future transactions of this kind made me struggle desperately. I sent for my lawyer, Stratton—an able fellow, as lawyers go, but, like most of this stupid, lazy human race, always ready to say “impossible” because saying so saves labour. “Stratton,” I said, “there must be a way round—there always is. Can’t I get what I want by an amendment to some other law that can be slipped through by the lobby of some other corporation as if for its benefit only? Take a week. Paw over the books and rake that brain of yours! There’s a hundred and fifty thousand in it for you if you find me the way round.”

“But the law—” he began.

I lost my temper—I always do when one of my men begins his reply to an order I’ve given him with the word “But.” “Don’t ‘but’ me, damn you,” said I. “I’m getting sick and tired of your eternal opposition. Crawford”—Crawford was my lawyer until I put him into the Senate—“used always to tell me how I could do what I wanted to do. You’re always telling me that I can’t do what I want to do.”

“I’m sorry to displease you, sir, but——”

“‘But’ again!” I exclaimed, sarcastically.

“Then, however,” he went on, with a conciliatory smile, “I’m not a legislator; I’m a lawyer.”

“Precisely,” said I. “And the only use I have for a lawyer is to show me how to do as I please, in spite of these wretched demagogues and blackmailers that control the statute-books. If you are as intelligent as Crawford led me to believe and as my own observation of you suggests, you’ll profit by this little talk we’ve had. Look round you at the men who are making the big successes in your profession nowadays—look at your predecessor, Crawford. Imitate them and stop casting about for ways of interpreting the law against your employer’s interest.”

Two days later he came to me in triumph. He had found the “way round.” I had my law slipped through, signed by the Governor, and safely put on the statute-book, the two bosses as unsuspicious as were the newspapers and the public. Then I came out in a public disavowal of my original purpose, denounced it as a crime against the people, and deplored that my railroad corporation should be unjustly accused of promoting it. You must fight the devil with fire.

Those two bosses—and the sensational newspapers that had been attacking them and my corporations—were astounded, and haven’t recovered yet. It will be six months before they realise that I have accomplished my purpose; even then they won’t be sure that I planned it, but will half believe it was my “luck.”

In passing, I may note that Stratton tells me I ought to pay him two hundred and fifty thousand dollars instead of one hundred and fifty thousand—for pulling me out of the hole! He has wholly forgotten having said “can’t be done” and “impossible” to me so many times that I finally had to stop him by cursing him violently. With their own vanity and their women-folks’ flattery for ever conspiring to destroy their judgment, it’s a wonder to me that men are able to get on at all. Indeed, they wouldn’t if they didn’t have masters like me over them.

After I had got my little joke on the bosses and the impertinent public safely on the statute-book, there remained the problem of how to take advantage of it without stirring up the sensational newspapers and the politicians, always ready to pander to the spirit of demagogy. I had my rights safely embodied in the law; but in this lawless time that is not enough. Instead of being respectful to the great natural leaders and deferential to their larger vision and larger knowledge, the people regard us with suspicion and overlook our services in their envy of the trifling commissions we get—for, what is the wealth we reserve for ourselves in comparison with the benefits we confer upon the country?

At this dinner which I have mentioned, both Burridge and Ridley were silent, and so my thoughts had no distraction. As I know that it is bad for my digestion to use my brain as I eat, I tried to start a conversation.

“Have you seen Aurora to-day?” I asked Burridge. She is my eldest daughter, just turned eighteen.

“She and Walter”—he is my second son, within a month or so of twenty-two—“are dining out this evening; she at Carnarvon’s, he at Longview’s. I think they meet at Mrs. Hollister’s dance and come home together.”

This was agreeable news. The names told me that my wife was at last succeeding in her social campaign, thanks to the irresistible temptation to the narrow aristocrats of the inner circle in the prospective fortunes of my children. While this social campaign of ours has its vanity side—and I here admit that I am not insensible to certain higher kinds of vanity—it also has a substantial business side. The greatest disadvantage I have laboured under—and at times it was serious—has been a certain suspicion of me as a newcomer and an adventurer. Naturally this has not been lessened by the boldness and swiftness of my operations. When I and my family are admitted on terms of intimacy and perfect equality among the people of large and old-established fortune, I shall be absolutely trusted in the financial world and shall be secure in the position of leadership which my brains have won for me and which I now maintain only by steady fighting.

“And Helen?” I went on. Helen is my other daughter, not yet twelve.

“She’s dining in her own sitting-room with her companion,” replied Burridge.

“I haven’t seen her for a day or two,” I said.

“Two weeks to-morrow,” answered Burridge.

Jack Ridley laughed, and I frowned. It irritates me for Ridley to note it whenever I am caught in seeming neglect of my children. He pretends not to believe that it is my sense of duty that makes me deprive myself of the family happiness of ordinary men for the sake of my larger duties. But he must know at the bottom that all my self-sacrifice is for my children, for my family, ultimately. I have the thankless, misunderstood toil; they have the enjoyment.

“Two weeks!” I protested; “it can’t be!”

“She came to me for her allowance this morning,” he said, “and she asked after you. She said your valet had told her you were staying here and were well. She said she’d like to see you some time—if you ever got round to it.”

This little picture of my domestic life did not tend to cheer me. Naturally, I went on to think of Jim. Ridley interrupted my thoughts by saying: “Have you been down on Long Island yet?”

This was going too far even for a “court fool”—his name for himself, not mine. Ridley is my pensioner, confidant, listening machine, and talking machine. He is of an old New York family, an honest, intelligent fellow, with an extravagant stomach and back. My wife engaged him, originally, to help her in her social campaigns. I saw that I could use him to better advantage, and he has gradually grown into my confidence.

In my lesser days, one of the things that most irritated me against the very rich was their habit of buying human beings, body and soul, to do all kinds of unmanly work, and I especially abhorred the “parasites”—so I called them—who hung about rich men, entertaining them, submitting to their humours, and bearing degradations and humiliations in exchange for the privileges of eating at luxurious tables, living in the colder corners of palaces, driving in the carriages of their patrons, and being received nominally as their social equals. But now I understand these matters better. It isn’t given to many men to be independent. As for the “parasites,” how should I do without Jack Ridley?

I can’t have friends. Friends take one’s time—they must be treated with consideration, or they become dangerous enemies. Friends impose upon one’s friendship—they demand inconvenient or improper, or, at any rate, costly favours which it is difficult to refuse. I must have companionship, and fate compels that my companion shall be my dependant, one completely under my control—a Jack Ridley. I look after his expensive stomach and back; he amuses me and keeps me informed as to the trifling matters of art, literature, gossip, and so forth, which I have no time to look up, yet must know if I am to make any sort of appearance in company. Really, next to my gymnasium, I regard poor old Jack as my most useful belonging, so far as my health and spirits are concerned.

To his impertinent reminder of my neglected duty I made no reply beyond a heavy frown. The rest of the dinner was eaten in oppressive silence, I brooding over the absence of cheerfulness in my life. They say it is my fault, but I know it is simply their stupidity in being unable to understand how to deal with a superior personality. It is my fate to be misunderstood, publicly and privately. The public grudgingly praises, often even derides, my philanthropies; the members of my family laugh at my generosities and self-sacrifices for them.

As I was going to my apartment and to bed, Ridley waylaid me. “You’re offended with me, old man?” he asked, his eyes moist and his lips trembling under his grey moustache. He weeps easily: at a glass of especially fine wine; over a sentimental story in a paper or magazine; if a grouse is cooked just right; when I am cross with him. And I think all his emotions, whether of heart or of stomach, are genuine—and probably about as valuable as most emotions.

“Not at all, not at all, Jack,” I said, reassuringly; “but you ought to be careful when you see I’m low in my mind.”

“Do go down to see the boy,” he went on, earnestly. “He’s a good boy at heart, as good as he is handsome and clever. Give him a little of your precious time and he’ll be worth more to you than all your millions.”

“He’s a young scalawag,” said I, pretending to harden. “I’m almost convinced that it’s my duty to drive him out and cut him off altogether. After all I’ve done for him! After all the pains I’ve taken with him!”

Ridley looked at me timidly, but found courage to say: “He told me he’d never talked with you so much as sixty consecutive minutes in his whole life!”

This touched me at the moment. I’m soft at times, where my family is concerned. “I’ll see; I’ll see,” I said. “Perhaps I can go down to him Sunday. But don’t annoy me about it again, Jack!” There’s a limit to my good-nature, even with poor old well-meaning Ridley.

But other matters pressed in, and it was the following Monday and then the following Saturday before I knew it. Then came the first Sunday in the month, and Burridge, as usual, brought in the preceding month’s domestic accounts as soon as I had settled myself at breakfast after my run and swim and rubdown in my “gym” in the basement. As a rule, at that time I’m in my best possible humour. My wife and children know it and lie in wait then with any particularly impudent requests for favours or particularly outrageous confessions that must be made. But on the first Sunday in the month even my “gym” can’t put me in good-humour. I am a liberal man. My large gifts to education and charity and my generosity with my family prove it beyond a doubt. My wife looks scornful when I speak of this. Her theory is that my public gifts are an exhibition of my vanity, and that my establishments, my yacht, etc., etc., are partly vanity, and partly my selfish passion for my own comfort. She, however, never attributes a good motive or instinct to me, or to any one else, nowadays. Really, the change in her since our modest days is incredible. It is amazing how arrogant affluence makes women.

But, as I was saying, my monthly bill-day is too much for my good-humour. It is not the money going out that I mind so much, though I’m not ashamed to admit that it is not so agreeable to me to see money going out as it is to see money coming in. The real irritation is the waste—the wanton, wicked, dangerous waste.

I can’t attend to details. I can’t visit kitchens, do marketing, superintend housekeepers and butlers, oversee stables, and buy all the various supplies. I can’t shop for furniture and clothing, and look after the entertainments. All those things are my wife’s business and duty. And she has a secretary, and a housekeeper, and Burridge, and Ridley, to assist her. Yet the bills mount and mount; the waste grows and grows. Extravagance for herself, extravagance for her children, thousands thrown away with nothing whatever to show for it! The money runs away like water at a left-on faucet.

The result is the almost complete estrangement between my wife and me. Every month we have a fierce quarrel over the waste, often a quarrel that lasts the month through and breaks out afresh every time we meet. She denounces me as a miser, a vulgarian. She goads me into furious outbursts before the children. What with my battles against stupidity and insolence down-town, and my battles against waste in my family, my life is one long contention. However, I suppose this is the lot of all the great men who play large parts on the world’s stage. No wonder those who fancy we are on earth to seek and find happiness regard life as a ghastly fraud.

“What’s the demnition total, Burridge?” I asked, when he appeared with his arms full of books and papers.

“Ninety-two thousand, four, twenty-six, fifty-one,” he answered, in a tone of abject apology.

I could not restrain an indignant expostulation. “That’s seventy-three hundred and four above last month. Impossible! You’ve made a mistake in adding.”

He went over his figures nervously and flushed scarlet. “I beg your pardon, sir,” he said, in a tone of terror. “The total is ninety-five thousand instead of ninety-two.”

Ten thousand-odd above month before last! Eighty-nine hundred above the same month last year! I had to restrain myself from physical violence to Burridge. I ordered him out of the room—giving as my reason anger at his mistake in addition. I wanted to hear no more, as I felt sure the details of the shameful waste would put me in a rage which would impair my health. The total was enough for my purpose—we were now living at the rate of more than a million dollars a year! I took the eleven o’clock train for my place on Long Island.

When I reached my railway station none of my traps was there. In my angry preoccupation I had forgotten to telephone from the Fifth Avenue house; and, of course, neither Pigott nor the butler nor Burridge nor Ridley nor any of my herd of blockhead servants had had the consideration to repair my oversight. Yet there are fools who say money will buy everything. Sometimes I think it won’t buy anything but annoyances.

So I had to go to my place in a rickety, smelly station-surrey—and that did not soothe my rage. However, as I drove into and through my grounds—there isn’t a finer park on Long Island—I began to feel somewhat better. There is nothing like lands and houses to give one the sensation of wealth, of possession. I have often gone into my vaults and have looked at the big bundles and boxes of securities; and, by setting my imagination to work, I have got some sort of notion how vast my wealth and power are. But bits of paper supplemented by imagination are not equal to the tangible, seeable things—just as a hundred-dollar bill can’t give one the sensation in the fingers and in the eyes that a ten-dollar gold piece gives. That is why I like my big houses and my city lots and my parked acres in the country—yes, and my yacht and carriages and furniture, my servants and horses and dogs, my family’s jewels and finery.

But the instant I entered the house my spirits soured again, curdled into an acid fury.

I had sent my son down there with his mother to await my sentence upon him for his crimes—his insults to me, his waste of nearly a million of my money, his violation of his word of honour, his forgery. I had been assuming that in those five weeks of waiting he was suffering from remorse and suspense, was thinking of his crimes against me and of my anger and justice. As I entered the large drawing-room unannounced, they were about to go in to luncheon. “They” means my wife and James, and Walter and Aurora, who had gone down to the country for the week-end. “They” means also ten others, six of whom were guests staying in the house. As I stood dumfounded, five more who had been to church came trooping in. I had gone, expecting a house of mourning. I had found a revel.

At sight of me the laughter and conversation died. My wife coloured. James looked abashed for a moment. Then—what a well-mannered, self-possessed dog he is!—he burst out laughing. “Fairly trapped!” he said. And he went on to explain to the others: “The governor and I had a little fall-out, and he sent me down here to play with the ashes. You’ve caught me with the goods on me, governor. It’s up to me—I’ve got to square myself. So I’ll pay by giving you the two prettiest young girls in the room to sit on either side of you at luncheon. Let’s go in, for I’m half-starved.”

As all the women in the room except three—including Aurora—were married, James’s remark was doubly adroit. What could I do but put aside my wrath and set my guests at their ease?

This was the less difficult to do as Natalie Bradish and Horton Kirkby were among the guests—and stopping in the house. I have long had my eye on Miss Bradish as the proper wife for James or Walter—whichever should commend himself to me as my fit successor at the head of the family I purpose to found with the bulk of my wealth. She is a handsome girl; she has a proud, distinguished look and manner; she will inherit several millions some day that can’t be distant, as her father is in hopelessly bad health; she comes of a splendid, widely connected family, and is extremely ambitious and free from sentimental nonsense. Young Kirkby is the very husband for Aurora. His great-grandfather founded their family securely in city real estate and lived long enough firmly to establish the tradition of giving the bulk of the fortune to the eldest male heir. Kirkby is not brilliant; but Aurora has brains enough for two, and he has a set of long, curved fingers that never relax their hold upon what’s in them.

After luncheon I drew my wife away to the sitting-room for the plain talk which was the object of my visit. As the presence of Miss Bradish and Kirkby in the house had lessened my anger on the score of my wife and son’s light-hearted way of looking at his crimes, I put forward the matter of the expense accounts.

“Burridge tells me the total for last month is—” I began, and paused. As I was speaking I was glancing round the room. I had not been in it for several years. I had just noted the absence of a Corot I bought ten years before and paid sixteen thousand dollars for. I don’t care for pictures or that sort of thing, any more than I care for the glitter of diamonds or the colours of gold and silver in themselves. I know that most of this talk of “art” and the like is so much rubbish and affectation. But works of art, like the precious stones and metals, have come to be the conventionally accepted standards of luxury, the everywhere recognised insignia of the aristocracy of wealth. So I have them, and add to my collection steadily just as I add to my collection of finely bound books that no one ever opens. What slaves of convention and ostentation we are!

“What’s become of the Corot that used to hang there?” I asked, suspiciously, because I had had so many experiences of my family’s trifling with my possessions.

My wife smiled scornfully. “I believe you carry round in your head an inventory of everything we’ve got, even to the last pot in the kitchen,” she said. “The Corot is safe. It’s hanging in my bedroom.”

In her bedroom! A Corot I’ve been offered twenty-five thousand dollars for, and she had hidden it away in her bedroom! I was irritated when she put it in her sitting-room where few people came, for it should have had a good place in our New York palace. But in her bedroom, where no one but the servants would ever have a chance to look at it!

“Why didn’t you put it in the attic or the cellar?” I asked.

She lifted her eyebrows and gave me an affected, disdainful glance. “I put it in my bedroom because I like to look at it,” she said.

I laughed. What nonsense! As if any sensible person—and she is unquestionably shrewdly sensible—ever looks at those things except when some one is by, noting their “devotion to art.” I said: “Certainly my family has the most amazing disregard of money—of value. If it were not——”

“You started to say something about last month’s accounts,” she interrupted.

“The total was ninety-five thousand,” I said, looking sternly at her. “You are now living at the rate of more than a million a year. In ten years we have jumped from one hundred thousand a year to a million a year. And this madness grows month by month.”

She—shrugged her shoulders!

“I came to say to you, madam—” I went on, furiously.

“Did you look at the items?” she cut in coldly.

“No,” I replied; “I could not trust myself to do it.”

“Twenty-seven thousand of last month’s expenses went toward paying a small instalment on your little place for your own amusement in the Adirondacks. I had nothing to do with it. None of us but you will ever go there.”

This was most exasperating. I can’t account for my leaping into such a trap, except on the theory that my preoccupation with the railway matters must have made me forget ordering that item into my domestic accounts instead of into my personal accounts down-town. Of course, my contention of my family’s extravagance was sound. But I had seemed to give the whole case away, had destroyed the effect of all I had said, and, as I glanced at my wife, I saw a triumphant, contemptuous smile in her eyes. “You are always trying to punish some one else for your own sins,” she said. “The truth is that the only truly prodigal member of the family is yourself.”

Me prodigal with my own wealth! But I did not answer her. One is at a hopeless disadvantage in discussion with a woman. They are insensible to reason and logic except when they can gain an advantage by using them. It’s like having to keep to the rules in a game where your antagonist keeps to them or makes his own rules as it suits him. “Nevertheless,” I said, “the waste in my establishments must stop and your son James must come to his senses. It was about him that I came.”

“Poor boy—he’s had such a bad example all his life!” she said. “My dear, we have no right to judge him.”

I knew that she, like him, was throwing up to me my transactions with Judson. And like him, she was taking the petty, narrow view of them. “Madam,” I said, “your son is a liar, forger, and thief.”

Just then there came a knock at the door and James’s voice called: “May I come in, mother?”

“No, go away, Jim. Your father and I are busy,” she called in reply.

I went to the door and opened it, beside myself with fury. “Come in!” I exclaimed. “It’s business that concerns you.”

He entered—tall and strong, his handsome face graver than I had ever seen it before. He closed the door behind him and stood looking from one to the other of us. “Well?” he said, “but—no abuse!”

Whenever James and I have come face to face in a crisis I have always had the, to me, maddening feeling that a will as strong as my own has been lifting its head defiantly against me. My wife and my son Walter deal with me by evasion and slippery trickery. My daughter Aurora wins from me, when I choose to let her, by cajolery or tears. Little Helen has never yet had to do with me in a serious matter, and I cannot remember her ever a me even the trifling favours which most children seek from their parents. But James has always played the high and haughty—and I am ashamed to think how often he has ridden me down and defeated me and gained his object. As I have looked upon him as entitled to peculiar consideration because I had planned for him one day to wear my mantle, he has had me at a disadvantage. But my indulgent conduct toward him only makes the blacker his conduct toward me.

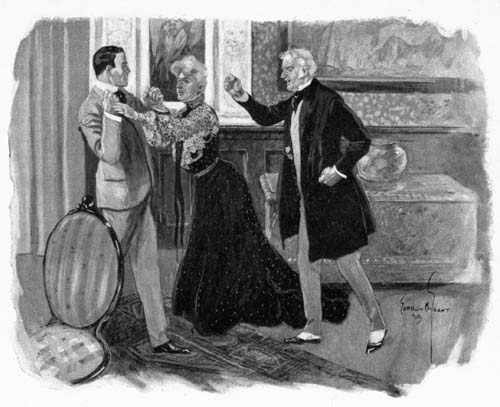

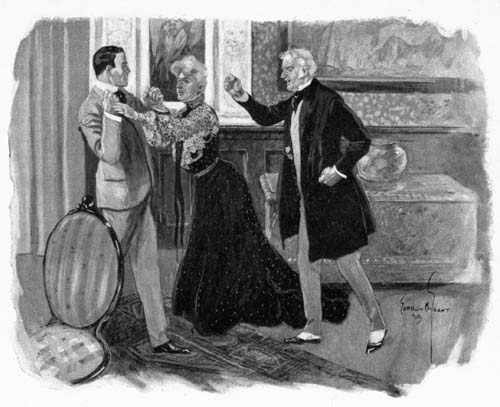

“‘You liar—you forger!’”

As he stood there that day, looking so calm and superior, I can’t describe the conflict of pride in him and hatred of him that surged up in me. I lost control of myself. I clinched my fists and shook them in his face. “You liar! You forger! You conscienceless——”

His mother rushed between us. “I knew it! I knew it!” she wailed. “Ever since he was a baby, I knew this day would come. Oh, my God! James, my husband—James, my son!”

James lowered the hand he had lifted to strike me. His face was pale and his eyes were blazing hate at me—I saw his real feeling toward me at last. How could I have overlooked it so long?

“Who would ever think you were my father?” he asked, in a voice that sounded to me like an echo of my own. “You—with hate in your face—hate for the son whom you poisoned before he was born, whom you have been poisoning ever since with your example. You—my father!”

The young scoundrel had taunted me into that calm fury which is so dreadful that I fear it myself—for, when I am possessed by it, there is no length to which I would not go. Our wills had met in final combat. I saw that I must crush him—the one human being who dared to oppose me and defy me, and he my own child who should have been deferential, grateful, obedient, unquestioning. “But I am not your father,” I said. “In my will I had made you head of the family, had given you two-thirds of my estate. I shall write a revocation here—immediately. I shall make a new will to-morrow.”

If the blow crushed him, he did not show it. He did not even wince as he saw forty millions swept away from him. “As you please,” he said, putting scorn into his face and voice—as if I could be fooled by such a pretence. The man never lived who could scorn a tenth, or even a fortieth, of forty millions. “I came into this room,” he went on, “to tell you how ashamed I was of what I have done—how vile and low I have felt. I didn’t come to apologise to you, but to my—my mother and to myself in your presence. I am still ashamed of what I did, of what you made me do. Do you know why I did it? Because your money, your millions, have changed you from a man into a monster. This wealth has injured us all—yes, even mother, noble though she is. But you—it has made you a fiend. Well, I wished to be independent of you. You have brought me up so that I could not live without luxury. But you haven’t destroyed in me the last spark of self-respect. And I decided to make a play for a fortune of my own. I—broke my word and speculated. I overreached—I saw my one hope of freeing myself from slavery to you slipping from me. I—I—no matter. What did matter after I’d broken my word? And I was justly punished. I lost—everything.”

As he flung these frightful insults at me my calm fury grew cold as well. “You will leave the house within an hour,” I said. “Your mother will make your excuses to her guests—I shall spare you the humiliation of a public disowning. During my lifetime you shall have nothing from me—no, nor from your mother. I shall see to that. In my will I shall leave you a trifling sum—enough to keep you alive. I am responsible to society that you do not become a public charge. And you may from this day continue on your way to the penitentiary without hindrance from those who were your kin.”

As I finished, he smiled. His smile grew broader, and became a laugh. “Very well, ex-father,” he said; “there’s one inheritance you can’t rob me of—my mind. I’ll lop off its rotten spots, and I think what’s left will