III

It has been two years and five months since I expelled James, yet my dissatisfaction with Walter has not decreased.

No doubt this is due in part to the grudge a man of my age who loves power and wealth must have against the impatient waiter for his throne and sceptre. No doubt, also, age and long familiarity with power have made me, perhaps, too critical of my fellow-beings and too sensitive to their shortcomings. But, after all allowances, I have real ground for my feeling toward Walter.

My principal heir and successor, who is to sustain my dignity after I am gone, and to maintain my name in the exalted position to which my wealth and genius have raised it, should have, above all else, two qualifications—character and an air of distinction.

Walter has neither.

My wife defends him for his lack of distinction in manner and look by saying that I have crushed him. “How could he have the distinction you wish,” she says, “when he has grown in the shadow of such a big, masterful, intolerant personality as yours?” There is justice in this. I admire distinction, or individuality, but at a distance. I cannot tolerate it in my immediate neighbourhood. There it tempts me to crush it. I suspect that it would have exasperated me even in one of my own flesh and blood. Indeed, at bottom, that may have had something to do with the beginnings of my break with James.

But whatever excuse there may be for Walter’s shifty, smirking, deprecating personality, which seems to me, at times, not a peg above the personality of a dancing-master, there is no excuse whatsoever for his lack of character.

I rarely talk to him so long as ten minutes without catching him in a lie—usually a silly lie, about nothing at all. In money matters he is not sensibly prudent, but downright miserly. That is not an unnatural quality in age, for then the time for setting the house in order is short. An avaricious young man is a monstrosity. I suppose that avarice is almost inseparable from great wealth, or even from the expectation of inheriting it. Just as power makes a man greedy of power, so riches make a man greedy of riches. But, granting that Walter has to be avaricious, why hasn’t he the wit to conceal it? It gives me no pleasure, nowadays, to give; in fact, it makes me suffer to see anything going out, unless I know it is soon to return bringing a harvest after its kind. Yet, I give—at least, I have given, and that liberally. Walter need not have made himself so noted and disliked for stinginess that he has been able to get into only one of the three fashionable clubs I wished him to join—and that one the least desirable.

His mother says he was excluded because the best people of our class resent my having elbowed and trampled my way into power too vigorously, and with too few “beg pardons,” and “if you pleases.” Perhaps my courage in taking my own frankly wherever I found it may have made his admission difficult, just as it has made our social progress slow. But it would not have excluded him—would not have made him patently unpopular where my money and the fear of me gains him toleration. A very few dollars judiciously spent would have earned him the reputation of a good fellow, generous and free-handed.

Your poor chap has to fling away everything he’s got to get that name, but a rich man can get it for what, to him, is a trifle. By means of a smile or a dinner I’d have to pay for anyhow, or perhaps by allowing him to ride a few blocks beside me in my brougham or victoria, I send a grumbler away trumpeting my praises. I throw an industry into confusion to get possession of it, and then I give a twentieth of the profits to some charity or college; instead of a chorus of curses, I get praise, or, at worst, silence. The public lays what it is pleased to call the “crime” upon the corporation I own; the benefaction is credited to me personally.

Nor has Walter the excuse for his lying and shifting and other moral lapses that a man who is making his way could plead.

I did many things in my early days which I’d scorn to do now. I did them only because they were necessary to my purpose. Walter has not the slightest provocation. When his mother says, “But he does those things because he’s afraid of you,” she talks nonsense. The truth is that he has a moral twist. It is one thing for a clear-sighted man of high purpose and great firmness, like myself, to adopt indirect measures as a temporary and desperate expedient; it’s vastly different for a Walter, with everything provided for him, to resort to such measures voluntarily and habitually.

Sometimes I think he must have been created during one of my periods of advance by ambuscade.

How ridiculous to fall out with honesty and truth when there’s any possible way of avoiding it! To do so is to use one’s last reserves at the beginning of a battle instead of at the crisis.

However, it’s Walter or nobody. I cannot abandon my life’s ambition, the perpetuation of my fortune and fame in a family line. Next to its shortness, life’s greatest tragedy for men of my kind is the wretched tools with which we must work. All my days I’ve been a giant, doing a giant’s work with a pygmy’s puny tools. Now, with the end—no, not near, but not so far away as it was—

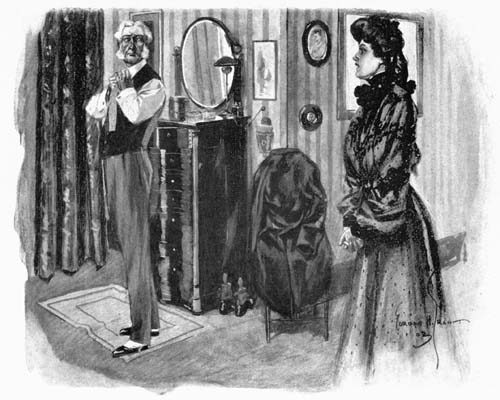

Just as I got home from the Chamber of Commerce dinner two weeks ago to-night, my wife was coming down to go to Mrs. Garretson’s ball. The great hall of my house, with its costly tapestries and carpets and statuary, is a source of keen pleasure to me. I don’t think I ever enter it, except when I’m much preoccupied, that I don’t look round and draw in some such satisfaction as a toper gets from a brimming glass of whiskey. But, for that matter, all the luxuries and comforts which wealth gives me are a steady source of gratification. The children of a man who rose from poverty to wealth may possibly—I doubt it—have the physical gratification in wealth blunted. But the man who does the rising has it as keen on the last day of healthy life as on the first day he became the owner of a carriage with somebody in his livery to drive him.

As my wife came down the wide marble stairs the great hall became splendid. I had to stop and admire her, or, rather, the way she shone and sparkled and blazed, becapped and bedecked and bedraped with jewels as she was. I have an eye that sees everything; that’s why I’m accused of being ferociously critical. I saw that there was something incongruous in her appearance—something that jarred. A second glance showed me that it was the contrast between her rubies and diamonds, in bands, in clusters, and in ropes, and her fading physical charms. She is not altogether faded yet—she is fifty to my sixty-four—and she has been for years spending several hours a day with masseuses, complexion-specialists, hair-doctors, and others of that kind. But she has reached the age where, in spite of doctoring and dieting and deception, there are many and plain signs of that double tragedy of a handsome, vain woman’s life—on the one hand, the desperate fight to make youth remain; on the other hand, the desperate fight to hide from the world the fact that it is about to depart for ever.

Naturally it depressed me that I could no longer think with pride of her beauty, and of how it was setting off my wealth. I must have shown what I was thinking, for she looked at me, first with anxious inquiry, then with frightened suspicion, as if guessing my thoughts.

Poor woman! I felt sorry for her.

Her life, for the past twenty years, has been based wholly on vanity. The look in my face told her, perhaps a few weeks earlier than she would have learned it from her mirror or some malicious bosom friend, that the basis of her life was swept away, and that her happiness was ended. She hurried past me, spoke savagely to the four men-servants who were jostling one another in trying to help her to her carriage, and drove away in her grandeur to the ball, probably as miserable a creature as there was on Manhattan Island that night.

I went up to my apartment, half depressed, half amused—I have too keen a sense of humour not to be amused whenever I see vanity take a tumble. As I reached my sitting-room I was in the full swing of my moralisings on the physical vanity of women, and on their silliness in setting store by their beauty after it has served its sole, legitimate, really useful purpose—has caught them husbands. Only mischief can come of beauty in a married woman. She should give it up, retire to her home, and remain there until it is time for her to bring out and marry off her grown sons and daughters. If my wife hadn’t been handsome she might have done this, and so might have continued to shine in her proper sphere—the care of her household and her children, the comfort of her husband.

As I reached this point in my moralisings I caught sight of my own face by the powerful light over my shaving glass.

I’ve never taken any great amount of interest in my face, or anybody else’s. I’ve no belief in the theory that you can learn much from your adversary’s expression. In a sense, the face is the map of the mind. But the map has so many omissions and mismarkings, all at important points, that time spent in studying it is time wasted. My plan has been to go straight along my own line, without bothering my head about the other fellow’s plans—much less about his looks. I think my millions prove me right.

As I was saying, I saw my face—suddenly, with startling clearness, and when my mind was on the subject of faces. The sight gave me a shock—not because my expression was sardonic and—yes, I shall confess it—cruel and bitterly unhappy. The shock came in that, before I recognised myself, I had said, “Who is this old man?”

The glass reflected wrinkles, bags, creases, hollows—signs of the old age of a hard, fierce life.

Curiously, my first comment on myself, seen as others saw me, was a stab into my physical vanity—not a very deep stab, but deep enough to mock my self-complacent jeers at my wife. Then I went on to wonder why I had not before understood the reason for many things I’ve done of late.

For example, I hadn’t realised why I put five hundred thousand dollars into a mausoleum. I did it without the faintest notion that my instinctive self was saying, “You’d better see to it at once that you’ll be fittingly housed—some day.” Again, I hadn’t understood why it was becoming so hard for me to persuade myself to keep up my public gifts.

I have always seen that for us men of great wealth gifts are not merely a wise, but a vitally necessary, investment.

Jack Ridley insists that I exaggerate the envy the lower classes feel for us. “You rich men think others are like yourselves,” he says. “Because all your thoughts are of money, you fancy the rest of the world is equally narrow and spends most of its time in hating you and plotting against you. Why, the fact is that rich men envy one another more than the poor envy them.” There’s some truth in this. The fellow with one million enviously hates the fellow with ten; as for most fellows with twenty or thirty, they can hardly bear to hear the fellows with fifty or sixty spoken of. But, in the main, Jack is wrong. I’ve not forgotten how I used to feel when I had a few hundred a year; and so I know what’s going on in the heads of people when they bow and scrape and speak softly, as they do to me. It means that they’re envying and are only too eager to find an excuse for hating. They want me to think that they like me.

I used to give chiefly because I liked the fame it brought me—also, a little, because it made me feel that I was balancing my rather ruthless financial methods by doing vast good with what many would have kept selfishly to the last penny. Latterly my chief motive has been more substantial; and I wonder how I could have let wealth-hunger so blind me, as it has in the past four or five years, that I have haggled over and cut my public gifts.

The very day after I saw my face in the mirror I definitely committed myself to my long tentatively promised gift of an additional four millions to the university which bears my name. I also arranged to get those four millions—but that comes later. Finally, I began to hasten my son Walter’s marriage to Natalie Bradish.

My son Walter!

It certainly isn’t lack of shrewdness that unfits him to be head of the family. Why do the qualities we most admire in ourselves, and find most useful there, so often irritate and even disgust us in another?

I have not told him that he is already the principal heir under the terms of my will. He will work harder to please me so long as he thinks the prize still withheld—still to be earned. He does not know how firmly my mind is set against James. So he never loses an opportunity to clinch my purpose. One day last week, in presence of his sister Aurora, I was reproving him for one of his many shortcomings, and, to enforce my reproof, was warning him that such conduct did not advance him toward the place from which his brother had been deposed.

His upper lip always twitches when he is about to launch one of those bits of craftiness he thinks so profound. The longer I live, the deeper is my contempt for craft—it so rarely fails to tangle and strangle itself in its own unwieldy nets. After his lip had twitched awhile, he looked furtively at Aurora. I looked also, and saw that she was a partner in his scheme, whatever it was.

“Well!” said I, impatiently, “what is it? Speak out!”

“You spoke of the position James lost,” he forced himself to say; “there wasn’t any such place, was there, Aurora?”

“No,” she answered; “James was deceiving you right along.”

“What do you mean?” I demanded.

Aurora looked nervously at Walter, and he said: “James often used to talk to us about your plans, and he always said that he wouldn’t let you make him your principal heir. He said he would disregard your will and would just divide the money up, giving a third to mother and making all us children equal heirs with him.”

It is amazing how the most astute man will overlook the simplest and plainest dangers. In all my thinking and planning on the subject of founding a family. I had never once thought of the possibility of my will being voluntarily broken by its chief beneficiary.

“What reason did he give?” I asked, for I could conceive no reason whatsoever.

Aurora and Walter were silent. Walter looked as if he wished he had not launched his torpedo at James.

“What reason, Aurora?” I insisted.

She flushed and stammered: “He said he—he didn’t want to be hated by mother and the rest of us. He said we’d have the right to hate him, and couldn’t help it if he should be low enough to profit by your—your——”

“My—what?”

“Your heartlessness.”

“And do you think my plan was heartless?” I asked.

“No,” said Aurora, but I saw that she thought “Yes.”

“You’ve a right to do as you wish with your own,” said Walter. “We know you’ll do what is for the best interest of us all. Even if you should leave us nothing, we’d still be in your debt. You owe us nothing, father. We owe you everything.”

Although this was simply a statement of a truth which I hold to be fundamental, it irritated me to hear him say it. I know too well what havoc self-interest works in the sense of right and wrong, and Walter would be the first of my children to insult my memory if he were to get less by a penny than any other of the family. Had I been concerning myself about what my wife and my children would think of me after I was gone, I should never have entertained the idea of founding a family. But men of large view and large wealth and large ambition do not heed these minor matters. When it comes to human beings, they deal in generals, not in particulars.

A fine world we should have if the masters of it consulted the feelings of those whom destiny compels them to use or to discard.

I looked at this precious pair of plotters satirically. “Naturally,” said I, “you never spoke to me of James’s purpose so long as there was a chance of your profiting by his intended treachery to me.” Then to Aurora I added: “I understand now why, for several months after James left, you persisted in begging me to take him back.”

Aurora burst into tears. As tears irritate me, I left the room. Thinking over the scandalous exhibition of cupidity which these children of mine had given, I was almost tempted to tear up my will and make a new one creating a vast public institution that would bear my name, and endowing it with the bulk of my wealth. I have often wondered why an occasional man of great wealth has done this. I now have no doubt that usually it has been because he was disgusted by the revolting greediness of his natural heirs. If rich men should generally adopt this course, I suspect their funerals would have less of the air of sunshine bursting through black clouds—it’s particularly noticeable in the carriages immediately behind the hearse.

Jack Ridley says my sense of humour is like an Apache’s. Perhaps that’s why the idea of a posthumous joke of this kind tickles me immensely. Were I not a serious man, with serious purposes in the world, I might perpetrate it.

The net result of Walter and Aurora’s effort to advance themselves—I wonder what Walter promised Aurora that induced her to aid him?—was that I formed a new plan. I resolved that Walter should marry at once. As soon as he has a male child I shall make a new will leaving it the bulk of my estate, and giving Walter only the control of the income for life—or until the child shall have become a man thirty years old.

That evening I ordered him to arrange with Natalie for a wedding within two months. I knew he would see her at the opera, as my wife had invited her to my box. I intended to ask him in the morning what he and she had settled upon, but before I had a chance I saw in my paper a piece of news that put him and her out of my mind for the moment.

James, so the paper said, was critically ill with pneumonia at his house in East Sixty-third Street, near Fifth Avenue. He has lived there ever since he was married, and has kept up a considerable establishment. I am certain that his wife’s dresses and entertainments are part of the cause of my wife’s rapid aging. Really, her hatred of that woman amounts to insanity. It amazes me, used as I am to the irrational emotions of women. I could understand her being exasperated by the social success of James and his wife. I confess that it has exasperated me—almost as much as has his preposterous luck in Wall Street. But there is undeniably a better explanation than luck for his and her social success. They say she has beauty and charm, and her entertainments show originality and talent, while my wife’s are commonplace and dull, in spite of the money she lavishes. But, in addition to those reasons, there are many of the upper-class people who hate me. Mine is a pretty big omelet; there is a lot of eggs in it; and, with every broken egg, somebody, usually somebody high up, felt robbed or cheated.

But I did not trust to my wife’s insane hate for James’s wife to keep her away from her son in his illness. I went straight to her. “I see that James is ill, or pretends to be,” I said. “Probably he and his wife are plotting a reconciliation.”

My wife has learned to mask her feelings behind a cold, expressionless face; but she has also learned to obey me. She often threatens, but she dares not act. I know it—and she knows that I know it.

“You will not go to him under any circumstances,” I went on—“neither you nor any of the rest of us. If you disobey, I shall at once rearrange my domestic finances. Thereafter you will go to Burridge for money whenever you want to buy so much as a paper of pins.”

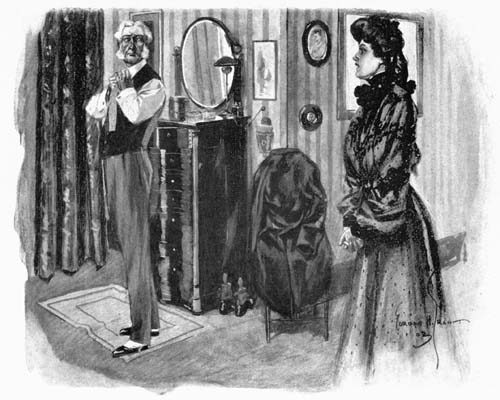

She was white—perhaps with fury, perhaps with dread, perhaps with both. I said no more, but left her as soon as I saw that she did not intend to reply. Toward six o’clock that evening I met Walter in the main hall of the first bedroom floor. He was for hurrying by me, but I stopped him. I have an instinct which tells me unerringly when to ask a question.

“Where are you going?” I asked.

He shifted from leg to leg; he, like most people, is never quite at ease in my presence; when he is trying to conceal some specific thing from me he becomes a victim of a sort of suppressed hysteria. “To the drawing-room,” he answered.

“Who’s there?” said I.

He shivered, then blurted it out: “James’s wife.”

“Why didn’t you tell me in the first place?”

He stammered: “I—wished to—to spare you—the——”

“Bah!” I interrupted. As if I could not read in his face that her coming had roused his fears of a reconciliation with James! “What are you going to say to her?”

“A message from mother,” he muttered.

“Have you seen your mother, or did you make up the message?”

“A servant brought mother her card and a note. I didn’t know she was in the house till mother sent for me and gave me the message to take down.”

“Will your mother see her?”

“No, indeed,” he replied, recovered somewhat; “mother won’t have anything to do with them.”

“Well, go on and deliver your message,” I said; “I’ll step into the little reception-room behind the drawing-room. See that you speak loud enough for me to hear every word.”

As I entered the reception-room, he entered the drawing-room. “Mother says,” he said—naturally, his voice was ridiculously loud and nervous—“that she has no interest in the information you sent her, and no acquaintance with the person to whom it relates.”

There was a silence so long that curiosity made me move within range of one of the long drawing-room mirrors. I saw her and Walter reflected, facing each other. She was so stationed that I had a plain view of her whole figure and of her face—the first time I had ever really seen her face. Her figure was drawn to its full height, and her bosom was rising and falling rapidly. Her head was thrown back, and upon poor Walter was beating the most contemptuous expression I ever saw coming from human eyes. No wonder even his back showed how wilted and weak he was.

As I watched, she suddenly turned her eyes; her glance met mine in the mirror. Before I could recover and completely drive the look of amusement from my face, she had waved Walter aside and was standing in front of me. “You heard what your son said!” she exclaimed; “what do you say?”

I liked her looks, and especially liked her voice. It was clear. It was magnetic. It was honest. When I wish to separate sheep from goats I listen to their voices, for voices do not often lie.

“I refuse to believe that he delivered my note to—to James’s mother.” There was a break in her voice as she spoke James’s name—it distinctly made my nerves tingle, unmoved though my mind was. “James is—is—” she went on, slowly, but not unsteadily—“the doctors say there’s no hope. And he—your son—sent me, and I am here when—when—but—what do you say?”

It is extraordinary what power there is in that woman’s personality. If Walter hadn’t been there I might have had to lash myself into a fury and insult her to save myself from being swept away. As it was, I looked at her steadily, then rang the bell. The servant came.

“Show this lady out,” I said, and I bowed and went to Walter in the drawing-room. I can only imagine how she must have felt. Nothing frenzies a woman—or a man—so wildly as to be sent away from a “scene” without a single insult given to gloat over or a single insult received to bite on.

The morning paper confirmed her statement of James’s condition. In fact, I didn’t have to wait until then, for toward twelve that night I heard the boys in the street bellowing an “extra” about him—that he was dying, and that none of his family had visited him. Those whose sense of justice is clouded by their feelings will be unable to understand why I felt no inclination to yield. Indeed, I do not expect to be understood in this except by those of my class—the men whose large responsibilities and duties have forced them to put wholly aside those feelings in which the ordinary run of mankind may indulge without harm. I don’t deny that I had qualms. I can sympathise now with those kings and great men who have been forced to order their sons to death. And I have charged against James the pangs he then caused me.

In the superficial view it may seem inconsistent that, while I stood firm, I was shocked by my wife’s insensibility. I had to do my duty, but she should have found it impossible to do hers. I could not, of course, rebuke her and Aurora for not transgressing my orders; but all that night and all the next day I wondered at their hardness, their unwomanliness. It seemed to me another illustration of the painful side of wealth and position—their demoralising effect upon women.

The late afternoon papers announced—truthfully—a favourable change in James’s condition. In defiance of the doctors’ decree of death, he had rallied. “It is that wife of his,” I said to myself. “Such a personality is a match for death itself.” I had a sense of huge relief. Indeed, it was not until I knew James wasn’t going to die that I realised how hard a fight my parental instinct had made against duty.

If I had liked Walter better I should not have been thus weak about James.

When I reached home and was about to undress for my bath and evening change, my daughter Helen knocked and entered. “Well?” said I.

She stood before me, tall and slim and golden brown—the colour is chiefly in her hair and lashes and brows, but there is a golden brown tinge in her skin; as for her eyes, they are more gold than brown, I think. Her dress reaches to her shoe-tops. With her hands clasped in front of her, she fixed her large, serious eyes upon me.

“I went to see James this morning,” she said; then seemed to be waiting—not in fear, but in courage—for my vengeance to descend.

I scowled and turned away to hide the satisfaction this gave me. At least there is one female in my family with a woman’s heart!

“Who put you up to it?” I demanded, sharply.

“‘Not to have told you would have been a lie.’”

“Nobody. I heard the boys calling in the street—and—I went.”

I turned upon her and looked at her narrowly. “Why do you tell me?” I asked.

“Because not to have told you would have been a lie.”

She said this quite simply. I had never been so astonished before in my life. “And what of that?” said I—a shameful question under the circumstances to put to a child; but I was completely off my guard, and I couldn’t believe there was not an underlying motive of practical gain.

“I do not care to lie,” she answered, her eyes upon mine. I found her look hard to withstand—a new experience for me, as I can usually compel any one’s gaze to shift.

“You’re a good child,” said I, patting her on the shoulder. “I shall not punish you this time. You may go.”

She flushed to the line of her hair, and her eyes blazed. She drew herself away from my hand and left me staring after her, more astonished than before.

A strange person—surely, a personality! She will be troublesome some day—soon.

With such beauty and such fine presence she ought to make a magnificent marriage.

I was free to take up Walter and Natalie again. After dinner I said to him, as we sat smoking: “Have you spoken to Natalie? What does she say? What date did you settle upon?”

He looked sheepishly from Burridge to Ridley, then appealingly at me. I laughed at this affectation of delicacy, but I humoured him by sending them away. “What date?” I repeated.

He twitched more than usual before he succeeded in saying: “She refuses to decide just yet.”

“Why?” I demanded.

“She says she doesn’t want to settle down so young.”

“Young!” I exclaimed. “Why, she’s twenty-one—out three seasons. What’s the matter with you, that you haven’t got her half frightened to death lest she’ll lose you?” With all he has to offer through being my son and my principal heir he ought to be able to settle the marriage on his own terms in every respect—and to keep the whip for ever afterward.

“I don’t know,” he replied; “she just won’t. I don’t think she cares much about—about the marriage.”

This was too feeble and foolish to answer. There isn’t a more sensible, better-brought-up girl in New York than Natalie. Her mother began training her in the cradle to look forward to being mistress of a great fortune. I knew she, and her mother and father too, had fixed on mine as the fortune as long ago as five years—she was only sixteen when I myself noted her making eyes at Jim and never losing a chance to ingratiate herself with me. Her temporising with Walter convinced me there was something wrong—and I suspected what. I went to see her, and got her to take a drive with me.

As my victoria entered the Park I began: “What’s the matter, Natalie? Why won’t you ‘name the day’? We’re old friends. You can talk to me as freely as to your own father.”

“I know it,” she replied; “you’ve always been so good to me—and you are so kind and generous.” There isn’t a better manner anywhere than Natalie’s. She has a character as strong and fine as her face.

“I’m getting old,” I went on, “and I want to see my boy settled. I want to see you my daughter, ready to take up your duties as head of my house.”

“Don’t try to hurry me,” she said, a trace of irritation in her voice. “I’m only twenty-one. I wish to have a little pleasure before I become as serious as I’ll have to be when I’m—your daughter.”

I noticed that she pointedly avoided saying “Walter’s