HIS DUTY

Amos Wickliff little suspected himself riding, that sunny afternoon, towards the ghastliest adventure of an adventurous life. Nevertheless, he was ill at ease. His horse was too light for his big muscles and his six feet two of bone. Being a merciful man to beasts, he could not ride beyond a jog-trot, and his soul was fretted by the delay. He cast a scowl down the dejected neck of the pony to its mournful, mismated ears, and from thence back at his own long legs, which nearly scraped the ground. “O Lord! ain’t I a mark on this horse!” he groaned. “We could make money in a circus!” With a gurgle of disgust he looked about him at the glaring blue sky, at the measureless, melancholy sweep of purple and dun prairie.

“Well, give me Iowa!” said Amos.

For a long while he rode in silence, but his thoughts were distinct enough for words. “What an amusing little scamp it was!”—thus they ran—“I believe he could mimic anything on earth. He used to give a cat and puppy fighting that I laughed myself nearly into a fit over. When I think of that I hate this job. Now why? You never saw the fellow to speak to him more than twice. Duty, Amos, duty. But if he is as decent as he’s got the name of being here, it’s rough—Hullo! River? Trees?” The river might be no more than the lightening rim of the horizon behind the foliage, but there was no mistake about the trees; and when Wickliff turned the field-glass, which he habitually carried, on them he could make out not only the river and the willows, but the walls of a cabin and the lovely undulations of a green field of corn. Half an hour’s riding brought him to the house and a humble little garden of sweet-pease and hollyhocks. Amos groaned. “How cursed decent it all looks! And flowers too! I have no doubt that his wife’s a nice woman, and the baby has a clean face. Everything certainly does combine to ball me up on this job! There she is; and she’s nice!”

A woman in a clean print gown, with a child pulling at her skirt, had run to the gate. She looked young. Her freckled face was not exactly pretty, but there was something engaging in the flash of her white teeth and her soft, black-lashed, dark eyes. She held the gate wide open, with the hospitality of the West. “Won’t you ’light, stranger?” she called.

“I’m bound for here,” replied Amos, telling his prepared tale glibly. “This is Mr. Brown’s, the photographer’s, ain’t it? I want him to come to the settlement with me and take me standing on a deer.”

“Yes, sir.” The woman spoke in mellow Southern accents, and she began to look interested, as suspecting a romance under this vain-glory. “Yes, sir. Deer you shot, I reckon. I’ll send Johnny D. for him. Oh, Johnny D.!”

A lath of a boy of ten, with sunburnt white hair and bright eyes, vaulted over a fence and ran to her, receiving her directions to go find uncle after he had cared for the gentleman’s horse.

“Your nephew, madam?” said Amos, as the lad’s bare soles twinkled in the air.

“Well, no, sir, not born nephew,” she said, smiling; “he’s a little neighbor boy. His folks live three miles further down the river; but I reckon we all think jest as much of him as if he was our born kin. Won’t you come in, sir?”

By this time she had passed under the luxuriant arbor of honeysuckle that shaded the porch, and she threw wide the door. The room was large. It was very tidy. The furniture was of the sort that can be easily transported where railways have to be pieced out with mule trails. But it was hardly the ordinary pioneer cabin. Not because there was a sewing-machine in one corner, for the sewing-machine follows hard on the heels of the plough; perhaps because of the white curtains at the two windows (curtains darned and worn thin by washing, tied back with ribbons faded by the same ministry of neatness), or the square of pretty though cheap carpet on the floor, or the magazines and the bunch of sweet-pease on the table, but most because of the multitude of photographs on the clumsy walls. They were on cards, all of the same size (not more than 8 by 10 inches), protected by glass, and framed in mossy twigs. Some of the pictures were scenes of the country, many of them bits of landscape near the house, all chosen with a marvellous elimination of the usual grotesque freaks of the camera, and with such an unerring eye for subject and for light and shade that the artist’s visions of the flat, commonplace country were not only picturesque but poetic. In the prints also were an extraordinary richness and range of tone. It did not seem possible that mere black and white could give such an effect of brilliancy and depth of color. An artist looking over this obscure photographer’s workmanship might feel a thrill like that which crinkles a flower-lover’s nerves when he sees a mass of azaleas in fresh bloom.

Amos was not an artist, but he had a camera at home, and he gave a gulp of admiration. “Well, he is great!” he sighed. “That beats any photographic work I ever saw.”

The wife’s eyes were luminous. “Ain’t he!” said she. “It ’most seems wicked for him to be farming when he can do things like that—”

“Why does he farm?”

“It’s his health. He caynt stand the climate East.”

“You are from the South yourself, I take it?”

“Yes, sir, Arkansas, though I don’t see how ever you guessed it. I met Mist’ Brown there, down in old Lawrence. I was teaching school then, and went to have my picture taken in his wagon. Went with my father, and he was so pleasant and polite to paw I liked him from the start. He nursed paw during his last sickness. Then we were married and came out here—You’re looking at that picture of little Davy at the well? I like that the best of all the ten; his little dress looks so cute, and he has such a sweet smile; and it’s the only one has his hair smooth. I tell Mist’ Brown I do believe he musses that child’s hair himself—”

“Papa make Baby’s hair pitty for picture!” cried the child, delighted to have understood some of the conversation.

“He’s a very pretty boy,” said Amos. “’Fraid to come to me, young feller?”

But the child saw too few to be shy, and happily perched himself on the tall man’s shoulder, while he studied the pictures. The mother appeared as often as the child.

“He’s got her at the best every time,” mused the observer; “best side of her face, best light on her nose. Never misses. That’s the way a man looks at his girl; always twists his eyes a little so as to get the best view. Plainly she’s in love with him, and looks remarkably like he was in love with her, damn him!” Then, with great civility, he asked Mrs. Brown what developer her husband used, and listened attentively, while she showed him the tiny dark room leading out of the apartment, and exhibited the meagre stock of drugs.

“I keep them up high and locked up in that cupboard with the key on top, for fear Baby might git at them,” she explained. She evidently thought them a rare and creditable collection. “I ain’t a bit afraid of Johnny D.; he’s sensible, and, besides, he minds every word Mist’ Brown tells him. He sets the world by Mist’ Brown; always has ever since the day Mist’ Brown saved him from drowning in the eddy.”

“How was that?”

“Why, you see, he was out fishing, and climbed out on a log and slipped someway. It’s about two miles further down the river, between his parents’ farm and ours; and by a God’s mercy we were riding by, Dave and the baby and I—the baby wasn’t out of long-clothes then—and we heard the scream. Dave jumped out and ran, peeling his clothes as he ran. I only waited to throw the weight out of the wagon to hold the horses, and ran after him. I could see him plain in the water. Oh, it surely was a dreadful sight! I dream of it nights sometimes yet; and he’s there in the water, with his wet hair streaming over his eyes, and his eyes sticking out, and his lips blue, fighting the current with one hand, and drifting off, off, inch by inch, all the time. And I wake up with the same longing on me to cry out, ‘Let the boy go! Swim! Swim!’”

“Well, did you cry that?” says Amos.

“Oh no, sir. I went in to him. I pushed a log along and climbed out on it and held out a branch to him, and someway we all got ashore—”

“What did you do with the baby?”

“I was fixing to lay him down in a soft spot when I saw a man was on the bank. He was jumping up and down and yelling: ‘I caynt swim a stroke! I caynt swim a stroke!’ ‘Then you hold the baby,’ says I; and I dumped poor Davy into his arms. When we got the boy up the bank he looked plumb dead; but Dave said: ‘He ain’t dead! He caynt be dead! I won’t have him dead!’ wild like, and began rubbing him. I ran to the man. If you please, there that unfortunate man was, in the same place, holding Baby as far away from him as he could get, as if he was a dynamite bomb that might go off at any minute. ‘Give me your pipe,’ says I. ‘You will have to fish it out of my pocket yourself,’ says he; ‘I don’t dast loose a hand from this here baby!’ And he did look funny! But you may imagine I didn’t notice that then. I ran back quick’s I could, and we rubbed that boy and worked his arms and, you may say, blowed the breath of life into him. We worked more’n a hour—that poor man holding the baby the enduring time: I reckon his arms were stiff’s ours!—and I’d have given him up: it seemed awful to be rumpling up a corpse that way. But Dave, he only set his teeth and cried, ‘Keep on, I will save him!’”

“And you did save him?”

“He did,” flashed the wife; “he’d be in his grave but for Dave. I’d given him up. And his mother knows it. And she said that if that child was not named Johnny ayfter his paw, she’d name him David ayfter Mist’ Brown; but seeing he was named, she’d do next best, give him David for a middle. And as calling him Johnny David seemed too long, they always call him Johnny D. But won’t you rest your hat on the bed and sit down, Mister—”

“Wickliff,” finished Amos; but he added no information regarding his dwelling-place or his walk in life, and, being a Southerner, she did not ask it. By this time she was getting supper ready for the guest. Amos was sure she was a good cook the instant his glance lighted on her snowy and shapely rolls. He perceived that he was to have a much daintier meal than he had ever had before in the “Nation,” yet he frowned at the wall. All the innocent, laborious, happy existence of the pair was clear to him as she talked, pleased with so good a listener. The dominant impression which her unconscious confidences made on him was her content.

“I reckon I am a natural-born farmer,” she laughed. “I fairly crave to make things grow, and I love the very smell of the earth and the grass. It’s beautiful out here.”

“But aren’t you ever lonesome?”

“Why, we’ve lots of neighbors, and they’re all such nice folks. The Robys are awful kind people, and only four miles, and the Atwills are only three, on the other side. And then the Indians drop in, but though I try to be good to them, it’s hard to like anybody so dirty. Dave says Red Horse and his band are not fair samples, for they are all young bucks that their fathers won’t be responsible for, and they certainly do steal. I don’t think they ever stole anything from us, ’cept one hog and three chickens and a jug of whiskey; but we always feed them well, and it’s a little trying, though maybe you’ll think I’m inhospitable to say so, to have half a dozen of them drop in and eat up a whole batch of light bread and all the meat you’ve saved for next day and a plumb jug of molasses at a sitting. That Red Horse is crazy for whiskey, and awful mean when he’s drunk; but he’s always been civil to us—There’s Mist’ Brown now!”

Wickliff’s first glance at the man in the doorway showed him the same undersized, fair-skinned, handsome young fellow that he remembered; he wanted to shrug his shoulders and exclaim, “The identical little tough!” but Brown turned his head, and then Amos was aware that the recklessness and the youth both were gone out of the face. At that moment it went to the hue of cigar ashes.

“Here’s the gentleman, David; my husband, Mist’ Wickliff,” said the wife.

“Papa! papa!” joyously screamed the child, pattering across the floor. Brown caught the little thing up and kissed it passionately; and he held his face for a second against its tiny shoulder before he spoke (in a good round voice), welcoming his guest. He was too busy with his boy, it may be, to offer his hand. Neither did Amos move his arm from his side. He repeated his errand.

Brown moistened his blue lips; a faint glitter kindled in his haggard eyes, which went full at the speaker.

“That’s what you want, is it?”

“Well, if I want anything more, I’ll explain it on the way,” said Amos, unsmilingly.

Brown swallowed something in his throat. “All right; I guess I can go,” said he. “To-morrow, that is. We can’t take pictures by moonlight; and the road’s better by daylight. Won’t you come out with me while I do my chores? We can—can talk it over.” In spite of his forced laugh there was undisguised entreaty in his look, and relief when Amos assented. He went first, saying under his breath, “I suppose this is how you want.”

Amos nodded. They went out, stepping down the narrow walk between the rows of hollyhocks to one side and sweet-pease to the other. Amos turned his head from side to side, against his will, subdued by the tranquil beauty of the scene. The air was very still. Only afar, on the river-bank, the cows were calling to the calves in the yard. A bell tinkled, thin and sweet, as one cow waded through the shallow water under the willows. After the dismal neutral tints of the prairie, the rich green of corn-field and grass looked enchanting, dipped as they were in the glaze of sunset. The purple-gray of the well-sweep was painted flatly against a sky of deepest, lustreless blue—the sapphire without its gleam. But the river was molten silver, and the tops of the trees reflected the flaming west, below the gold and the tumbled white clouds. Turn one way, the homely landscape held only cool, infinitely soft blues and greens and grays; turn the other, and there burned all the sumptuous dyes of earth and sky.

“It’s a pretty place,” said Brown, timidly.

“Very pretty,” Amos agreed, without emotion.

“I’ve worked awfully hard to pay for it. It’s all paid for now. You saw my wife.”

“Nice lady,” said Amos.

“By ⸺, she is!” The other man swore with a kind of sob. “And she believes in me. We’re happy. We’re trying to lead a good life.”

“I’m inclined to think you’re living as decently and lawfully as any citizens of the United States.” The tone had not changed.

“Well, what are you going to do?” Brown burst forth, as if he could bear the strain no longer.

“I’m going to do my duty, Harned, and take you to Iowa.”

“Will you listen to me first? All you know is, I killed—”

But the officer held up his hand, saying in the same steady voice, “You know whatever you say may be used against you. It’s my duty to warn—”

“Oh, I know you, Mr. Wickliff. Come behind the gooseberry bushes where my wife can’t see us—”

“It’s no use, Harned; if you talked like Bob Ingersoll or an angel, I have to do my duty.” Nevertheless he followed, and leaned against the wall of the little shed that did duty for a barn. Harned walked in front of him, too miserably restless to stand still, nervously pulling and breaking wisps of hay between his fingers, talking rapidly, with an earnestness that beaded his forehead and burned in his imploring eyes. “All you know about me”—so he began, quietly enough—“all you know about me is that I was a dissipated, worthless photographer, who could sing a song and had a cursed silly trick of mimicry which made him amusing company; and so I was trying to keep company with rich fellows. You don’t know that when I came to your town I was as innocent a country lad as you ever saw, and had a picture of my dead mother in my Bible, and wrote to my father every week. He was a good man, my father. Lucky he died before he found out about me. And you don’t know, either, that at first, keeping a little studio on the third story, with a folding-bed in the studio, and doing my cooking on the gas-jet, I was a happy man. But I was. I loved my art. Maybe you don’t call a photographer an artist. I do. Because a man works with the sun instead of a brush or a needle, can’t he create a picture? And do you suppose a photographer can’t hunt for the soul in a sitter as well as a portrait-painter? Can’t a photographer bring out light and shade in as exquisite gradations as an etcher? Artist! Any man that can discover beauty, and can express it in any shape so other men can see it and love it and be happy on account of it—he’s an artist! And I don’t give a damn for a critic who tries to box up art in his own little hole!” Harned was excitedly tapping the horny palm of one hand with the hard, grimy fingers of the other. Amos thought of the white hands that he used to take such pains to guard, and then he looked at the faded check shirt and the patched overalls. Harned had been a little dandy, too fond of perfumes and striking styles.

“I was an artist,” said Harned. “I loved my art. I was happy. I had begun to make reputation and money when the devil sent him my way. He was an amateur photographer; that’s how we got acquainted. When he found I could sing and mimic voices he was wild over me, flattered me, petted me, taught me all kinds of fool habits; ruined me, body and soul, with his friendship. Well, he’s dead; and God knows she wasn’t worth a man’s life; but he did treat me mean about her, and when I flew at him he jeered at me, and he took advantage of my being a little fellow and struck me and cuffed me before them all; then I went crazy and shot him!” He stopped, out of breath. Wickliff mused, frowning. The man at his mercy pleaded on, gripping those slim, roughened hands of his hard together: “It ain’t quite so bad as you thought, is it, Mr. Wickliff? For God’s sake put yourself in my place! I went through hell after I shot him. You don’t know what it is to live looking over your shoulder! Fear! fear! fear! Day and night, fear! Waking up, maybe, in a cold sweat, hearing some noise, and thinking it meant pursuit and the handcuffs. Why, my heart was jumping out of my mouth if a man clapped me on the shoulder from behind, or hollered across the street to me to stop. Then I met my wife. You need not tell me I had no right to marry. I know it; I told myself so a hundred times; but I couldn’t leave her alone with her poor old sick father, could I? And then I found out that—that it would be hard for her, too. And I was all wore out. Man, you don’t know what it is to be frightened for two years? There wasn’t a nerve in me that didn’t seem to be pulled out as far as it would go. I married her, and we hid ourselves out here in the wilderness. You can say what you please, I have made her happy; and she’s made me. If I was to die to-night, she’d thank God for the happy years we’ve had together; just as she’s thanked Him every night since we were married. The only thing that frets her is me giving up photography. She thinks I could make a name like Wilson or Black. Maybe I could; but I don’t dare; if I made a reputation I’d be gone. I have to give it up, and do you suppose that ain’t a punishment? Do you suppose it’s no punishment to sink into obscurity when you know you’ve got the capacity to do better work than the men that are getting the money and the praise? Do you suppose it doesn’t eat into my heart every day that I can’t ever give my boy his grandfather’s honest name?—that I don’t even dare to make his father’s name one he would be proud of? Yes, I took his life, but I’ve given up all my chances in the world for it. My only hope was to change as I grew older and be lost, and the old story would die out—”

“It might; but you see he had a mother,” said Wickliff; “she offers five thousand—”

“It was only one thousand,” interrupted Harned.

“One thousand first year. She’s raised a thousand every year. She’s a thrifty old party, willing to pay, but not willing to pay any more than necessary. When it got to five thousand I took the case.”

Harned looked wistfully about him. “I might raise four thousand—”

“Better stop right there. I refused fifty thousand once to let a man go.”

“Excuse me,” said Harned, humbly; “I remember. I’m so distracted I can’t think of anything but Maggie and the baby. Ain’t there anything that will move you? I’ve paid for that thing. I saved a boy’s life once—”

“I know; I’ve seen the boy.”

“Then you know I fought for his life; I fought awful hard. I said to myself, if he lived I’d know it was the sign God had forgiven me. He did live. I’ve paid, Mr. Wickliff, I’ve paid in the sight of God. And if it comes to society, it seems to me I’m a good deal more use to it here than I’d be in a State’s prison pegging shoes, and my poor wife—”

He choked; but there was no softening of the saturnine gloom of Wickliff’s face.

“You ought to tell that all to the lawyer, not to me,” said Wickliff. “I’m only a special officer, and my duty is to my employer, not to society. What’s more, I am going to perform it. There isn’t anything that can make it right for me to balk on my duty, no matter how sorry I feel for you. No, Mr. Harned, if you live and I live, you go back to Iowa with me.”

“HARNED HID HIS FACE”

Harned in utter silence studied the impassive face, and it returned his gaze; then he threw his arm up against the shed, and hid his own face in the crook of his elbow. His shoulders worked as in a strong shudder, but almost at once they were still, and when he turned his features were blank and steady as the boards behind them.

“I’ve just one favor to ask,” said he; “don’t tell my wife. You have got to stay here to-night; it will be more comfortable for you, if I don’t say anything till after you’ve gone to bed. Give me a chance to explain and say good-bye. It will be hard enough for her—”

“Will you give me your parole you won’t try to escape?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Nor kill yourself?”

Harned started violently, and he laughed. “Do you think I’d kill myself before poor Maggie? I wouldn’t be so mean. No, I promise you I won’t either run away or kill myself or play any kind of trick on you to-night. Does it go?”

“It goes,” responded Amos, holding out his hand; “and I’ll give you a good reputation in court, too, for being a good citizen now. That will have weight with the judge. And if you care to know it, I’m mighty sorry for you.”

“Thank you, Mr. Wickliff,” said Harned; but he had not seemed to see the hand; he was striding ahead.

“That man means to kill himself,” thought Amos; “he’s too blamed resigned. He’s got it all planned before. And God help the poor beggar! I guess it’s the best thing he can do for himself. Lord, but it’s hard sometimes for a man to do his duty!”

The two men walked along, at first both mute, but no sooner did they come well in view of the kitchen door than they began to talk. Amos hoped there was nothing in the rumors of Indian troubles.

“There’s only one band could make trouble,” said Harned. “Red Horse is a mean Indian, educated in the agency schools, and then relapsed. Say, who’s that running up the river-bank? Looks like Mrs. Roby’s sister. She’s got the baby.” His face and voice changed sharply, he crying out, “There’s something wrong with that woman!” and therewith he set off running to the house at the top of his speed. Half-way, Amos, running behind him, could hear a clamor of women’s voices, rising and breaking, and loud cries. Mrs. Brown came to the doorway, beckoning with both hands, screaming for them to hurry.

When they reached the door they could see the new-comer. She was huddled in a rocking-chair, a pitiful, trembling shape, wet to the skin, her dank cotton skirts dripping, bareheaded, and her black hair blown about her ghastly face; and on her breast a baby, wet as she, smiling and cooing, but with a great crimson smouch on its tiny shoulder. Near her appeared Johnny D.’s white head. He was pale under his freckles, but he kept assuring her stoutly that uncle wouldn’t let the Indians get them.

The woman was so spent with running that her words came in gasps. “Oh, git ready! Fly! They’ve killed the Robys. They’ve killed sister and Tom. They killed the children. Oh, my Lord! children! They was clinging to their mother, and crying to the Indians to please not to kill them. Oh, they pretended to be friendly—so’s to git in; and we cooked ’em up such a good supper; but they killed every one, little Mary and little Jim—I heard the screeches. I picked up the baby and run. I jumped into the river and swum to the boat—I don’t know how I done it—oh, be quick! They’ll be coming! Oh, fly!”

Harned turned on Amos. “Flying’s no good on land, but maybe the boat—you’ll help?”

“Of course,” said Amos. “Here, young feller, can you scuttle up to the roof-tree and reconnoitre with this field-glass?—you’re considerably lighter on your feet than me. Twist the wheel round here till you can see plain. There’s a hole, I see, up to the loft. Is there one out on the roof? Then scuttle!”

Mrs. Brown pushed the coffee back on the stove. “No use it burning,” said she; and Amos admired her firm tones, though she was deadly pale. “If we ain’t killed we’ll need it. Dave, don’t forget the camera. I’ll put up some comforters to wrap the children in and something to eat.” She was doing this with incredible quickness as she spoke, while Harned saw to his gun and the loading of a pistol.

The pistol she took out of his hands, saying, in a low, very gentle voice, “Give that to me, honey.”

He gave her a strange glance.

“They sha’n’t hurt little Davy or me, Dave,” she answered, in the same voice.

Little Davy had gone to the woman and the baby, and was looking about him with frightened eyes; his lip began to quiver, and he pointed to the baby’s shoulder: “Injuns hurt Elly. Don’t let Injuns hurt Davy!”

The wretched father groaned.

“No, baby,” said the mother, kissing him.

“Hullo! up there,” called Amos. “What do you see?”

The shrill little voice rang back clearly, “They’re a-comin’, a terrible sight of them.”

“How many? Twenty?”

“I guess so. Oh, uncle, the boat’s floated off!”

“Didn’t you fasten it?” cried Harned.

“God forgive me!” wailed the woman, “I don’t know!”

Harned sat down in the nearest chair, and his gun slipped between his knees. “Maggie, give us a drink of coffee,” said he, quietly. “We’ll have time for that before they come.”

“Can’t we barricade and fight?” said Amos, glaring about him.

“Then they’ll get behind the barn and fire that, and the wind is this way.”

“We’ve got to save the women and the kids!” cried Amos. At this moment he was a striking and terrible figure. The veins of his temple swelled with despair and impotent fury; his heavy features were transfigured in the intensity of his effort to think—to see; his arms did not hang at his sides; they were held tensely, with his fist clinched, while his burning eyes roamed over every corner of the room, over every picture. In a flash his whole condition changed, his muscles relaxed, his hands slid into his pockets, he smiled the strangest and grimmest of smiles. “All right,” said he. “Ah—Brown, you got any whiskey? Fetch it.” The women stared, while Harned passively found a jug and placed it before him.

“Now some empty bottles and tumblers.”

“There are some empty bottles in the dark room; what do you mean to do?”

“Mean to save you. Brace up! I’ll get them. And you, Mrs. Brown, if you’ve got any paregoric, give those children a dose that will keep them quiet, and up in the loft with you all. We’ll hand up the kids. Listen! You must keep quiet, and keep the children quiet, and not stir, no matter what infernal racket you may hear down here. You must! To save the children. You must wait till you hear one of us, Brown or me, call. See? I depend on you, and you must depend on me!”

Her eyes sought her husband’s; then, “I’m ready, sir,” she said, simply. “I’ll answer for Johnny D., and the others I’ll make quiet.”

“That’s the stuff,” cried Amos, exultantly. “I’ll fix the red butchers. Only for God’s sake hustle!”

He turned his back on the parting to enter the dark room, and when he came back, with his hands full of empty bottles, Harned was alone.

“I told her it was our only chance,” said Harned; “but I’m damned if I know what our only chance is!”

“Never mind that,” retorted Amos, briskly. He was entirely calm; indeed, his face held the kind of grim elation that peril in any shape brings to some natures. “You toss things up and throw open the doors, as if you all had run away in a big fright, while I’ll set the table.” And, as Harned feverishly obeyed, he carefully filled the bottles from the demijohn. The last bottle he only filled half full, pouring the remains of the liquor into a tumbler.

“All ready?” he remarked; “well, here’s how,” and he passed the tumbler to Harned, who shook his head. “Don’t need a brace? I don’t know as you do. Then shake, pardner, and whichever one of us gets out of this all right will look after the women. And—it’s all right?”

“Thank you,” choked Harned; “just give the orders, and I’m there.”

“You get into the other room, and you keep there, still; those are the orders. Don’t you come out, whatever you hear; it’s the women’s and the children’s lives are at stake, do you hear? And no matter what happens to me, you stay there, you stay still! But the minute I twist the button on that door, let me in, and be ready with your hatchet—that will be handiest. Savez?”

“Yes; God bless you, Mr. Wickliff!” cried Harned.

“Pardner it is, now,” said Wickliff. They shook hands. Then Harned shut himself in the closet. He did not guess Wickliff’s plan, but that did not disturb the hope that was pumping his heart faster. He felt the magnetism of a born leader and an intrepid fighter, and he was Wickliff’s to the death. He strained his ears at the door. A chair scraped the boards; Wickliff was sitting down. Immediately a voice began to sing—Wickliff’s voice changed into a tipsy man’s maudlin pipe. He was singing a war-song:

“‘We’ll rally round the flag, boys, we’ll rally once again,

Shouting the battle-cry of Freedom!’”

The sound did not drown the thud of horses’ hoofs outside. They sounded nearer. Then a hail. On roared the song, all on one note. Wickliff couldn’t carry a tune to save his soul, and no living man, probably, had ever heard him sing.

“‘And we’ll drive the savage crew from the land we love the best,

Shouting the battle-cry—’

“Hullo! Who’s comin’? Injuns—mean noble red men? Come in, gen’lemen all.”

The floor shook. They were all crowding in. There was a din of guttural monosyllables and sibilant phrases all fused together, threatening and sinister to the listener; yet he could understand that some of them were of pleasure. That meant the sight of the whiskey.

“P-play fair, gen’lemen,” the drunken voice quavered, “thas fine whiskey, fire-water. Got lot. Know where’s more. Queer shorter place ever did see. Aller folks skipped. Nobody welcome stranger. Ha, ha!—hic!—stranger found the whiskey, and is shelerbrating for himself. Help yeself, gen’lemen. I know where there’s shum—shum more—plenty.”

Dimly it came to Harned that here was the man’s bid for his life. They wouldn’t kill him until he should get the fresh supply of whiskey.

“Where Black Blanket gone?” grunted Red Horse. Harned knew his voice.

“Damfino,” returned the drunken accents, cheerfully. “L-lit out, thas all I know. Whas you mean, hitting each orrer with bottles? Plenty more. I’ll go get it. You s-shay where you are.”

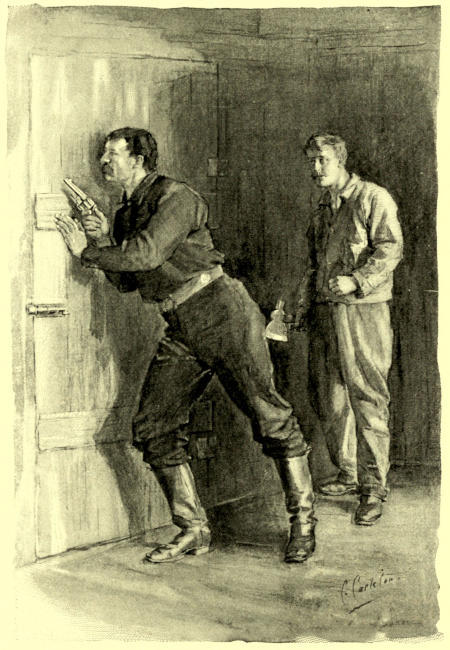

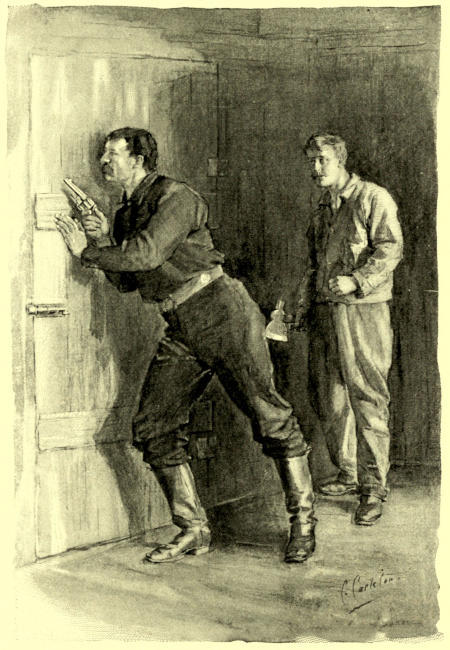

The blood pounded through Harned’s veins at the sound of the shambling step on the floor. His own shoulders involuntarily hunched themselves, quivering as if he felt the tomahawk between them. Would they wait, or would they shy something at him and kill him the minute his back was turned? God! what nerve the man had! He was not taking a step the quicker—ah! Wickliff’s fingers were at the fastening. He flung the door back. Even then he staggered, keeping to his rôle. But the instant he was over the threshold the transformation came. He hurled the door back and threw his weight against it, quick as a cat. His teeth were set in a grin of hate, his eyeballs glittered, and he shook his pistol at the door.

“Come on now, damn you!” he yelled. “We’re ready.”

Like an echo to his defiance, there rose an awful and indescribable uproar from the room beyond—screams, groans, yells, and simultaneously the sound of a rush on the door. But for a minute the door held.

The clatter of tomahawk blades shook it, but the wood was thick; it held.

“Hatchet ready, pard?” said Wickliff. “When you feel the door give, slip the bolt to let ’em tumble in, and then strike for the women and the kids; strike hard. I’ll empty my pop into the heap. It won’t be such a big one if the door holds a minute longer.”

“What are they doing in there?” gasped Harned.

“‘IT WON’T BE SUCH A BIG ONE IF THE DOOR HOLDS’”

“They’re dying in there, that’s what,” Wickliff replied, between his teeth, “and dying fast. Now!”

The words stung Harned’s courage into a rush, like whiskey. He shot the bolt, and three Indians tumbled on them, with more—he could not see how many more—behind. Then the hatchet fell. It never faltered after that one glimpse Harned had of the thing at one Indian’s belt. He heard the bark of the pistol, twice, three times, the heap reeling; the three foremost were on the floor. He had struck them down too; but he was borne back. He caught the gleam of the knife lurching at him; in the same wild glance he saw Wickliff’s pistol against a broad red breast, and Red Horse’s tomahawk in the air. He struck—struck as Wickliff fired; struck not at his own assailant, but at Red Horse’s arm. It dropped, and Wickliff fired again. He did not see that; he had whirled to ward the other blow. But the Indian knife made only a random, nerveless stroke, and the Indian pitched forward, doubling up hideously in the narrow space, and thus slipping down—dead.

“That’s over!” called Wickliff.

Now Harned perceived that they were standing erect; they two and only they in the place. Directly in front of them lay Red Horse, the blood streaming from his arm. He was dead; nor was there a single living creature among the Indians. Some had fallen before they could reach the door at which they had flung themselves in the last access of fury; some lay about the floor, and one—the one with the knife—was stiff behind Harned in the dark room.

“Look at that fellow,” called Harned. “I didn’t hit him; he may be shamming.”

“I didn’t hit him either,” said Wickliff, “but he’s dead all the same. So are the others. I’d been too, I guess, but for your good blow on that feller’s arm. I saw him, but you can’t kill two at once.”

“How did you do it?”

“Doped the whiskey. Cyanide of potassium from your photographic drugs; that was the quickest. Even if they had killed you and me, it would work before they could get the women and children. The only risk was their not taking it, and with an Indian that wasn’t so much. Now, pardner, you better give a hail, and then we’ll hitch up and get them safe in the settlement till we see how things are going.”

“And then?” said Harned, growing red.

Amos gnawed at the corners of his mustache in rather a shamefaced way. “Then? Why, then I’ll have to leave you, and make the best story I can honestly for the old lady. Oh yes, damn it! I know my duty; I never went back on it before. But I never went back on a pardner either; and after fighting together like we have, I’m not up to any Roman-soldier business; nor I ain’t going to give you a pair of handcuffs for saving my life! So run outside and holler to your frau.”

Left alone, Wickliff gazed about him in deep meditation, which at last found outlet in a few pensive sentences. “Clean against the rules of war; but rules of war are as much wasted on Injuns as ‘please’ on a stone-deaf man! And I simply had to save the women and children. Still it’s a pretty sorry lay-out to pay five thousand dollars for the privilege of seeing. But it’s a good deal worse to not do my duty. I shall never forgive myself. But I never should forgive myself for going back on a pardner either. I guess all it comes to is, duty’s a cursed blind trail!”