THE HYPNOTIST

There were not so many carriages in the little Illinois city with chop-tailed horses, silver chains, and liveried coachmen that the clerks in the big department shop should not know the Courtlandt landau, the Courtlandt victoria, and the Courtlandt brougham (Miss Abbie Courtlandt’s private equipage) as well as they knew Madam Courtlandt, Mrs. Etheridge, or Miss Abbie. Two of the shop-girls promptly absorbed themselves in Miss Abbie, one May morning, when she alighted from the brougham. For an instant she stood, as if undecided, looking absently at the window, which happened to be a huge kaleidoscope of dolls.

A tall man and two ragged little girls were staring at the dolls also. Both the girls were miserably thin, and one of them had a bruise on her cheek. The man was much too well clad and prosperous to belong to them. He stroked a drooping black mustache, and said, in the voice of a man accustomed to pet children, whether clean or dirty, “Like these dolls better than yours, sissy?”—at the same time smiling at the girl with the bruised cheek.

A sharp little pipe answered, “I ’ain’t got no doll, mister.”

“No, she ’ain’t,” added the other girl; “but I got one, only it ’ain’t got no right head. Pa stepped on its head. I let her play with it, and we made a head outer a corn-cob. It ain’t a very good head.”

“I guess not,” said the man, putting some silver into her hand; “there, you take that, little sister, and you go in and buy two dolls, one for each of you; and you tell the young lady that waits on you just what you told me. And if there is any money left, you go on over to that bakery and fill up with it.”

The children gave him two rapid, bewildered glances, clutched the money, and darted into the store without a word. The man’s smiling eyes as they turned away encountered Miss Abbie’s, in which was a troubled interest. She had taken a piece of silver from her own purse. He smiled, as perceiving a kindly impulse that matched his own; and she, to her own later surprise, smiled too. The smile changed in a flash to a startled look; all the color drifted out of her face, and she took a step forward so hastily that she stumbled on her skirt. Recovering herself, she dropped her purse; and a man who had just approached went down on one knee to pick it up. But the tall man was too quick for him; a long arm swooped in between the other’s outstretched hand and the gleaming bit of lizard-skin on the bricks. The new-comer barely avoided a collision. He did not take the escape with good-humor, scowling blackly as he made a scramble, while still on his knee, at something behind the tall man’s back. This must have been a handkerchief, since he immediately presented a white flutter to Miss Courtlandt, bowing and murmuring, “You dropped this too, I guess, madam.”

“Yes, thank you,” stammered Miss Courtlandt; “thank you very much, Mr. Slater.” She entered the store by his side, but at the door she turned her head for a parting nod of acknowledgment to the other. He remained a second longer, staring at the dolls, and gnawing the ends of his mustache, not irritated, but sharply thoughtful.

Thus she saw him, glancing out again, once more, when inside the store. And through all the anguish of the moment—for she was in a dire strait—she felt a faint pang that she should have been rude to this kind stranger. In a feeble way she wondered, as they say condemned criminals wonder at street sights on the way to the gallows, what he was thinking of. But had he spoken his thought aloud she had not been the wiser, since he was simply saying softly to himself, “Well, wouldn’t it kill you dead!”

Miss Abbie stopped at the glove-counter to buy a pair of gloves. As she walked away she heard distinctly one shop-girl’s sigh and exclamation to the other, “My, I wish I was her!”

A kind of quiver stirred Miss Abbie’s faded cold face. Her dark gray eyes recoiled sidewise; then she stiffened from head to heel and passed out of the store.

To a casual observer she looked annoyed; in reality she was both miserable and humiliated. And once back in the shelter of the brougham her inward torment showed plainly in her face.

Abigail Courtlandt was the second daughter of the house; never so admired as Mabel, the oldest, who died, or Margaret, the youngest, who married Judge Etheridge, and was now a widow, living with her widowed mother.

Abigail had neither the soft Hayward loveliness of Mabel and her mother, nor the haughty beauty of Margaret, who was all a Courtlandt, yet she was not uncomely. If her chin was too long, her forehead too high, her ears a trifle too large, to offset these defects she had a skin of exquisite texture, pale and clear, white teeth, and beautiful black brows.

She was thin, too thin; but her dressmaker was an artist, and Abbie would have been graceful were she not so nervous, moving so abruptly, and forever fiddling at something with her fingers. When she sat next any one talking, it did not help that person’s complacency to have her always sink slightly on the elbow further from her companion, as if averting her presence. An embarrassed little laugh used to escape her at the wrong moment. Withal, she was cold and stiff, although some keen people fancied that her coldness and stiffness were no more than a mask to shield a morbid shyness. These same people said that if she would only forget herself and become interested in other people she would be a lovable woman, for she had the kindest heart in the world. Unfortunately all her thoughts concentred on herself. Like many shy people, Abbie was vain. Diffidence as often comes from vanity, which is timid, as from self-distrust. Abbie longed passionately not only to be loved, but to be admired. She was loved, assuredly, but she was not especially admired. Margaret Etheridge, with her courage, her sparkle, and her beauty, was always the more popular of the sisters. Margaret was imperious, but she was generous too, and never oppressed her following; only the rebels were treated to those stinging speeches of hers. Those who loved Margaret admired her with enthusiasm. No one admired poor Abbie with enthusiasm. She was her father’s favorite child, but he died when she was in short dresses; and, while she was dear to all the family, she did not especially gratify the family pride.

Her hungry vanity sought refuge in its own creations. She busied herself in endless fictions of reverie, wherein an imaginary husband and an imaginary home of splendor appeased all her longings for triumph. While she walked and talked and drove and sewed, like other people, only a little more silent, she was really in a land of dreams.

Did her mother complain because she had forgotten to send the Book Club magazines or books to the next lawful reader, she solaced herself by visions of a book club in the future which she and “he” would organize, and a reception of distinguished elegance which “they” would give, to which the disagreeable person who made a fuss over nothing (meaning the reader to whom reading was due) should not be invited—thereby reducing her to humility and tears. But even the visionary tears of her offender affected Abbie’s soft nature, and all was always forgiven.

Did Margaret have a swarm of young fellows disputing over her card at a ball, while Abbie must sit out the dances, cheered by no livelier company than that of old friends of the family, who kept up a water-logged pretence of conversation that sank on the approach of the first new-comer or a glimpse of their own daughters on the floor, Abbie through it all was dreaming of the balls “they” would give, and beholding herself beaming and gracious amid a worshipping throng.

These mental exercises, this double life that she lived, kept her inexperienced. At thirty she knew less of the world than a girl in her first season; and at thirty she met Ashton Clarke. Western society is elastic, or Clarke never would have been on the edges even; he never did get any further, and his morals were more dubious than his position; but he was Abbie’s first impassioned suitor, and his flattering love covered every crack in his manners or his habits. Men had asked her to marry them before, but never had a man made love to her. For two weeks she was a happy woman. Then came discovery, and the storm broke. The Courtlandts were in a rage—except gentle Madam Courtlandt, who was broken-hearted and ashamed, which was worse for Abbie. Jack, the older brother, was summoned from Chicago. Ralph, the younger, tore home on his own account from Yale. It was really a testimony to the family’s affection for Abbie that she created such a commotion, but it did not impress her in that way. In the end she yielded, but she yielded with a sense of cruel injustice done her.

Time proved Clarke worse than her people’s accusations; but time did not efface what the boys had said, much less what the girls had said. They forgot, of course; it is so much easier to forget the ugly words that we say than those that are said to us. But she remembered that Jack felt that Abbie never did have any sense, and that Ralph raged because she did not even know a cad from a gentleman, and that Margaret, pacing the floor, too angry to sit still, would not have minded so much had Abbie made a fool of herself for a man; but she didn’t wait long enough to discover what he was; she positively accepted the first thing with a mustache on it that offered!

Time healed her heart, but not her crushed and lacerated vanity. And it is a question whether we do not suffer more keenly, if less deeply, from wounds to the self-esteem than to the heart. Generally we mistake the former for the latter, and declare ourselves to have a sensitive heart, when what we do have is only a thin-skinned vanity!

But there was no mistake about Abbie’s misery, however a moralist might speculate concerning the cause. She suffered intensely. And she had no confidant. She had not even her old fairyland of fancy, for love and lovers were become hateful to her. At first she went to church—until an unlucky difference with the rector’s wife at a church fair. Later it was as much her unsatisfied vanity and unsatisfied heart as any spiritual confusion that led her into all manner of excursions into the shadowy border-land of the occult. She was a secret attendant on table-tippings and séances; a reader of every kind of mystical lore that she could buy; an habitual consulter of spiritual mediums and clairvoyants and seventh sons and daughters and the whole tribe of charlatans. But the family had not noticed. They were not afraid of the occult ones; they were glad to have Abbie happy and more contented; and they concerned themselves no further, as is the manner of families, being occupied with their own concerns.

And so unguarded Abbie went to her evil fate. One morning, with her maid Lucy, she went to see “the celebrated clairvoyant and seer, Professor Rudolph Slater, the greatest revealer of the future in this or any other century.”

Lucy looked askance at the shabby one-story saloons on the street, and the dying lindens before the house. Her disapproval deepened as they went up the wooden steps. The house was one of a tiny brick block, with wooden cornices, and unshaded wooden steps in need not only of painting but scrubbing.

The door opened into an entry which was dark, but not dark enough to conceal the rents in the oil-cloth on the floor or the blotches on the imitation oak paper of the walls.

Lucy sniffed; she was a faithful and affectionate attendant, and she used considerable freedom with her mistress. “I don’t know about there being spirits here, but there’s been lots of onions!” remarked Lucy. Nor did her unfavorable opinion end with the approach to the sorcerer’s presence. She maintained her wooden expression even sitting in the great man’s room and hearing his speech.

Abbie did not see the hole in the green rep covering of the arm-chair, nor the large round oil-stain on the faded roses of the carpet, nor the dust on the Parian ornaments of the table; she was too absorbed in the man himself.

If his surroundings were sordid, he was splendid in a black velvet jacket and embroidered shirt-front sparkling with diamonds. He was a short man, rather thick-set, and although his hair was gray, his face was young and florid. The gray hair was very thick, growing low on his forehead and curling. Abbie thought it beautiful. She thought his eyes beautiful also, and spoke to Lucy of their wonderful blue color and soul-piercing gaze.

“I thought they were just awful impudent,” said Lucy. “I never did see a man stare so, Miss Abbie; I wanted to slap him!”

“But his hair was beautiful,” Abbie persisted; “and he said it used to be straight as a poker, but the spirits curled it.”

“Why, Miss Abbie,” cried Lucy, “I could see the little straight ends sticking out of the curls, that come when you do your hair up on irons. I’ve frizzed my hair too many times not to know them.”

“But, Lucy,” said Abbie, in a low, shocked voice, “didn’t you feel something when he put on those handcuffs and sat before the cabinet in the dark, and his control spoke, and we saw the hands? What do you think of that?”

“I think it was him all the time,” said Lucy, doggedly.

“But, Lucy, why?”

“Finger-nails were dirty just the same,” said Lucy. Nor was there any shaking her. But Abbie, under ordinary circumstances the most fastidious of women, had not noted the finger-nails; one witching sentence had captured her.

The moment he took her hand he had started violently. “Excuse me, madam,” said he, “but are you not a medium yourself?”

“No—at least, I never was supposed to be,” fluttered Abbie, blushing.

“Then, madam, you don’t perhaps realize that you yourself possess marvellous psychic power. I never saw any one who had so much, when it had not been developed.”

To-day Abbie ground her teeth and wrung her hands in an impotent agony of rage, remembering her pleasure. He would not take any money; no, he said, there had been too much happiness for him in meeting such a favorite of the spiritual influences as she.

“But you will come again,” he pleaded; “only don’t ask me to take money for such a great privilege. You caynt see the invisible guardians that hover around you!”

His refusal of her gold piece completed his victory over Abbie’s imagination. She was sure he could not be a cheat, since he would not be paid. She did come again; she came many times, always with Lucy, who grew more and more suspicious, but could not make up her mind to expose Abbie’s folly to her people. “Think of all the things she gives me!” argued Lucy. “Miss Abbie’s always been a kind of stray sheep in the family; they are all kind of hard on her. I can’t bear to be the one to get her into trouble.”

So Lucy’s conscience squirmed in silence until the fortune-teller persuaded Abbie to allow him to throw her into a trance. The wretched woman in the carriage cowered back farther into the shade, living over that ghastly hour when Lucy at her elbow was as far away from her helpless soul as if at the poles. How his blue eyes glowed! How the flame in them contracted to a glittering spark, like the star-tip of the silver wand, waving and curving and interlacing its dazzling flashes before her until her eyeballs ached! How of a sudden the star rested, blinking at her between his eyes, and she looked; she must look at it, though her will, her very self, seemed to be sucked out of her into the gleaming whirlpool of that star!

She made a feeble rally under a woful impression of fright and misery impending, but in vain; and, with the carelessness of a creature who is chloroformed, she let her soul drift away.

When she opened her eyes, Lucy was rubbing her hands, while the clairvoyant watched the two women motionless and smiling.

The fear still on her prompted her first words, “Let me go home now!”

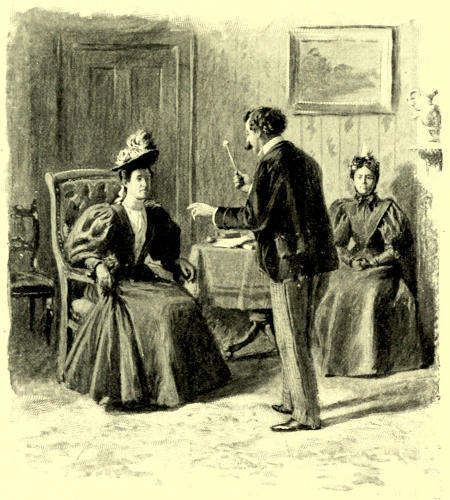

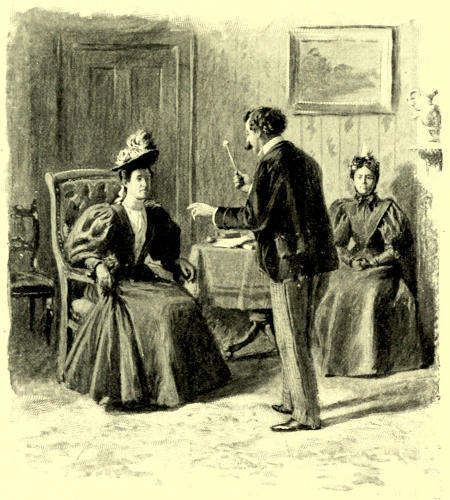

“Not now,” begged the conjurer; “you must go into a trance again. I want you to see something that will be very interesting to you. Please, Miss Courtlandt.” He spoke in the gentlest of tones, but there was a repressed assurance about his manner that was infuriating to Lucy.

“Miss Abbie’s going home,” she cried, angrily; “we ain’t going to have any more of this nonsense. Come, Miss Abbie.” She touched her on her arm, but trembling Abbie fixed her eyes on the conjurer, and he, in that gentle tone, answered:

“Certainly, if she wishes; but she wants to stay. You want to stay, Miss Courtlandt, don’t you?”

“Yes, I want to stay,” said Abbie; and her heart was cold within her, for the words seemed to say themselves, even while she struggled frantically against the utterance of them.

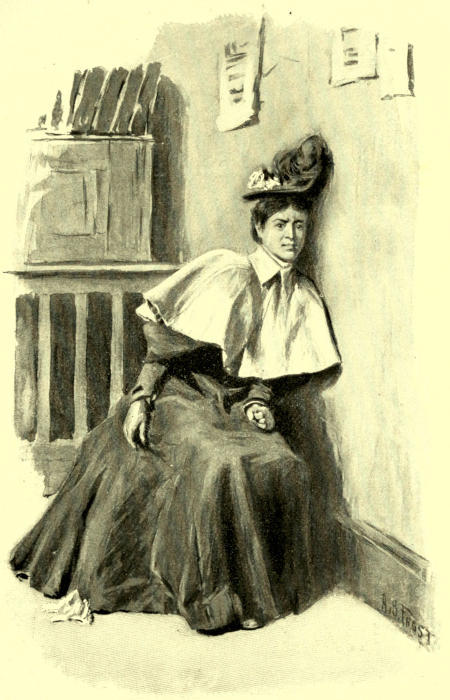

“‘SHE MUST LOOK AT IT’”

“Do you mean it, Miss Abbie?” the girl repeated, sorely puzzled.

“Certainly, just once more,” said Miss Abbie. And she sat down again in her chair.

What she saw she never remembered. Lucy said it was all nonsense she talked, and, anyhow, she whispered so low that nobody could catch more than a word, except that she seemed to be promising something over and over again. In a little while the conjurer whispered to her, and with a few passes of his hand consciousness returned. She rose, white and shaken, but quite herself again. He bade the two good-bye, and bowed them out with much suavity of manner. Abbie returned not a single word. As they drove home, the maid spoke, “Miss Abbie, Miss Abbie—you won’t go there again, will you?”

“Never,” cried Abbie—“never!”

But the next morning, after a sleepless night, there returned the same horrible, dragging longing to see him; and with the longing came the same fear that had suffocated her will the day before—a fear like the fear of dreams, formless, reasonless, more dreadful than death.

Impelled by this frightful force that did not seem to have anything to do with her, herself, she left the house and boarded a street-car. She felt as if a demon were riding her soul, spurring it wherever he willed. She went to a little park outside the city, frequented by Germans and almost deserted of a week-day. And on her way she remembered that this was what she had promised him to do.

He was waiting to assist her from the car. As he helped her alight, she noticed his hands and his nails. They were neat enough; yet she suddenly recalled Lucy’s words; and suddenly she saw the man, in his tasteless, expensive clothes, with his swagger and the odor of whiskey about him, as any other gentlewoman would have seen him. Her fright had swept all his seer’s glamour away; he was no longer the mystical ruler of the spirit-world; he was a squalid adventurer—and her master!

He made her realize that in five minutes. “You caynt help yourself, Miss Courtlandt,” he said, and she believed him.

Whether it were the influence of a strong will on a hysterical temperament and a morbidly impressible fancy, or whether it were a black power from the unseen, beyond his knowledge but not beyond his abuse, matters little so far as poor Abbie Courtlandt was concerned; on either supposition, she was powerless.

She left him, hating him as only slavery and fear can hate; but she left him pledged to bring him five hundred dollars in the morning and to marry him in the afternoon; and now, having kept her word about the money, she was driving home, clinching in her cold fingers the slip of paper containing the address of a justice of the peace in the suburbs, where she must meet him and be bound to this unclean vulture, who would bear her away from home and kindred and all fair repute and peace.

A passion of revolt shook her. She must meet him? Why must she? Why not tear his address to bits? Why not drive fast, fast home, and tell her mother that she was going to Chicago about some gowns that night? Why not stay there at Jack’s, and let this fiend, who harried her, wait in vain? She twisted the paper and ground her teeth; yet she knew that she shouldn’t tear it, just as we all know we shall not do the frantic things that we imagine, even while we are finishing up the minutest details the better to feign ourselves in earnest. Poor, weak Abbie knew that she never would dare to confess her plight to her people. No, she could never endure another family council of war.

“There is only one way,” she muttered. Instead of tearing the paper she read it:

“Be at Squire L. B. Leitner’s, 398 S. Miller Street, at 3 p.m. sharp.”

And now she did tear the odious message, flinging the pieces furiously out of the carriage window.

The same tall, dark, square-shouldered man that she had seen in front of the shop-window was passing, and immediately bent and picked up some of the shreds. For an instant the current of her terror turned, but only for an instant. “What could a stranger do with an address?” She sank into the corner, and her miserable thoughts harked back to the trap that held her.

Like one in a nightmare, she sat, watching the familiar sights of the town drift by, to the accompaniment of her horses’ hoofs and jingling chains. “This is the last drive I shall ever take,” she thought.

She felt the slackening of speed, and saw (still in her nightmare) the broad stone steps and the stately, old-fashioned mansion, where the daintiest of care and the trimmest of lawns had turned the old ways of architecture from decrepitude into pride.

Lunch was on the table, and her mother nodded her pretty smile as she passed. Abbie had a box of flowers in her hand, purchased earlier in the morning; these she brought into the dining-room. There were violets for her mother and American Beauties for Margaret. “They looked so sweet I had to buy them,” she half apologized. Going through the hall, she heard her mother say, “How nice and thoughtful Abbie has grown lately!” And Margaret answered, “Abbie is a good deal more of a woman than I ever expected her to be.”

All her life she had grieved because—so she morbidly put it to herself—her people despised her; now that it was too late, was their approval come to her only to be flung away with the rest? She returned to the dining-room and went through the farce of eating. She forced herself to swallow; she talked with an unnatural ease and fluency. Several times her sister laughed at her words. Her mother smiled on her fondly. Margaret said, “Abbie, why can’t you go to Chicago with me to-night and have a little lark? You have clothes to fit, too; Lucy can pack you up, and we can take the night train.”

“I would,” chimed in Mrs. Courtlandt. “You look so ill, Abbie. I think you must be bilious; a change will be nice for you. And I’ll ask Mrs. Curtis over for a few days while you are gone, and we will have a little tea-party of our own and a little lark for ourselves.”

Never before had Margaret wished Abbie to accompany her on “a little lark.” Abbie assented like a person in a dream; only she must go down to the bank after luncheon, she said.

Up-stairs in her own chamber she gazed about the pretty furnishings with blank eyes. There was the writing-desk that her mother gave her Christmas, there glistened the new dressing-table that Margaret helped her about finishing, and there was the new paper with the sprawly flowers that she thought so ugly in the pattern, and took under protest, and liked so much on the walls. How often she had been unjust to her people, and yet it had turned out that they were right! Her thoughts rambled on through a thousand memories, stumbling now into pit-falls of remorse over long-forgotten petulance and ingratitude and hardenings of her heart against kindness, again recovering and threading some narrow way of possible release, only to sink as the wall closed again hopelessly about her.

For the first time she arraigned her own vanity as the cause of her long unhappiness. Well, it was no use now. All she could do for them would be to drift forever out of their lives. She opened the drawer, and took a vial from a secret corner. “It is only a little faintness and numbness, and then it is all over,” she thought, as she slipped the vial into the chatelaine bag at her waist. In a sudden gust of courage she took it out again; but that instinctive trusting to hope to the last, which urges the most desperate of us on delay, held her hand. She put back the vial, and, without a final glance, went down the stairs. It was in her heart to have one more look at her mother, but at the drawing-room door she heard voices, and happening to glance up at the clock, she saw how near the time the hour was; so she hurried through the hall into the street.

During the journey she hardly felt a distinct thought. But at intervals she would touch the outline of the vial at her waist.

The justice’s office was in the second story of a new brick building that twinkled all over with white mortar. Below, men laughed, and glasses and billiard-balls clicked behind bright new green blinds. A steep, dark wooden stairway, apparently trodden by many men who chewed tobacco and regarded the world as their cuspidor, led between the walls up to a narrow hall, at the farther end of which a door showed on its glass panels the name L. B. Leitner, J.P.

Abbie rapped feebly on the glass, to see the door instantly opened by Slater himself. He had donned a glossy new frock-coat and a white tie. His face was flushed.

“I didn’t intend you should have to enter here alone,” he exclaimed, drawing her into the room with both hands; “I was just going outside to wait for you. Allow me to introduce Squire Leitner. Squire, let me make you acquainted with Miss Courtlandt, the lady who will do me the honor.”

He laughed a little nervous laugh. He was plainly affecting the manner of the fortunate bridegroom, and not quite at ease in his rôle. Neither of the two other men in the room returned any answering smile.

The justice, a bald, gray-bearded, kindly, and worried-looking man, bowed and said, “Glad to meet you, ma’am,” in a tone as melancholy as his wrinkled brow.

“Squire is afraid you are not here with your own free-will and consent, Abbie,” said Slater, airily; “but I guess you can relieve his mind.”

At the sound of her Christian name (which he had never pronounced before) Abbie turned white with a sort of sick disgust and shame. But she raised her eyes and met the intense gaze of the tall, dark man that she had seen before. He stood, his elbow on the high desk and his square, clean-shaven chin in his hand. He was neatly dressed, with a rose in his button-hole, and an immaculate pink-and-white silk shirt; but he hardly seemed (to Abbie) like a man of her own class. Nevertheless, she did not resent his keen look; on the contrary, she experienced a sudden thrill of hope—something of the same feeling she had known years and years ago, when she ran away from her nurse, and a big policeman found her, both her little slippers lost in the mud of an alley, she wailing and paddling along in her stocking feet, and carried her home in his arms.

“Yes, Miss Courtlandt”—she winced at the voice of the justice—“it is my duty under the—hem—unusual circumstances of this case, to ask you if you are entering into this—hem—solemn contract of matrimony, which is a state honorable in the sight of God and man, by the authority vested in me by the State of Illinois—hem—to ask you if you are entering it of your own free-will and consent—are you, miss?”

Abbie’s sad gray eyes met the magistrate’s look of perplexed inquiry; her lips trembled.

“Are you, Abbie?” said the clairvoyant, in a gentle tone.

“Yes,” answered Abbie; “of my own free-will and consent.”

“I guess, professor, I must see the lady alone,” said the justice, dryly.

“You caynt believe it is a case of true love laffs at the aristocrats, can you, squire?” sneered Slater; “but jest as she pleases. Are you willing to see him, Abbie?”

“Whether Miss Courtlandt is willing or not,” interrupted the tall man, in a mellow, leisurely voice, “I guess I will have to trouble you for a small ‘sceance’ in the other room, Marker.”

“And who are you, sir?” said Slater, civilly, but with a truculent look in his blue eyes.

“This is Mr. Amos Wickliff, of Iowa, special officer,” the justice said, waving one hand at the man and the other at Abbie.

Wickliff bowed in Abbie’s direction, and saluted the fortune-teller with a long look in his eyes, saying:

“Wasn’t Bill Marker that I killed out in Arizona your cousin?”

“My name ain’t Marker, and I never had a cousin killed by you or anybody,” snapped back the fortune-teller, in a bigger and rounder voice than he had used before.

Wickliff merely narrowed his bright black eyes, opened a door, and motioned within, saying, “Better.”

The fortune-teller scowled, but he walked through the door, and Wickliff, following, closed it behind him.

Abbie looked dumbly at the justice. He sighed, rubbed his hands together, and placed a chair against the wall.

“There’s a speaking-tube hole where we used to have a tube, but I took it out, ’cause it was too near the type-writer,” said he. “It’s just above the chair; if you put your ear to that hole I guess it would be the best thing. You can place every confidence in Mr. Wickliff; the chief of police here knows him well; he’s a perfect gentleman, and you don’t need to be afraid of hearing any rough language. No, ma’am.”

Abbie’s head swam; she was glad to sit down. Almost mechanically she laid her ear to the hole.

The first words audible came from Wickliff. “Certainly I will arrest you. And I’ll take you to Toronto to-night, and you can settle with the Canadian authorities about things. Rosenbaum offers a big reward; and Rosenbaum, I judge, is a good fellow, who will act liberally.”

“I tell you I’m not Marker,” cried Slater, fiercely, “and it wouldn’t matter a damn if I was! Canada! You caynt run a man in for Canada!”

Wickliff chuckled. “Can’t I?” said he; “that’s where you miss it, Marker. Now I haven’t any time to fool away; you can take your choice: go off peacefully—I’ve a hack at the door—and we’ll catch the 5:45 train for Toronto, and there you shall have all the law and justice you want; or you can just make one step towards that door, or one sound, and I’ll slug you over the head, and load you into the carriage neatly done up in chloroform, and when you wake up you’ll be on the train with a decent gentleman who doesn’t know anything about international law, but does know me, and wouldn’t turn his head if you hollered bloody murder. See?”

“That won’t go down. You caynt kidnap me that way! I’ll appeal to the squire. No, no! I won’t! Before God, I won’t—I was jest fooling!”

The voice of terror soothed Abbie’s raw nerves like oil on a burn. “He’s scared now, the coward!” she rejoiced, savagely.

“There’s where we differ, then,” retorted Wickliff; “I wasn’t.”

“That’s all right. Only one thing: will you jest let me marry my sweetheart before I go, and I’ll go with you like a holy lamb; I will, by—”

“No swearing, Marker. That lady don’t want to marry you, and she ain’t going to—”

“Ask her,” pleaded Slater, desperately. “I’ll leave it with her. If she don’t say she loves me and wants to marry me, I’ll go all right.”

Abbie’s pulses stood still.

“Been trying the hypnotic dodge again, have you?” said Wickliff, contemptuously. “Well, it won’t work this time. I’ve got too big a curl on you.”

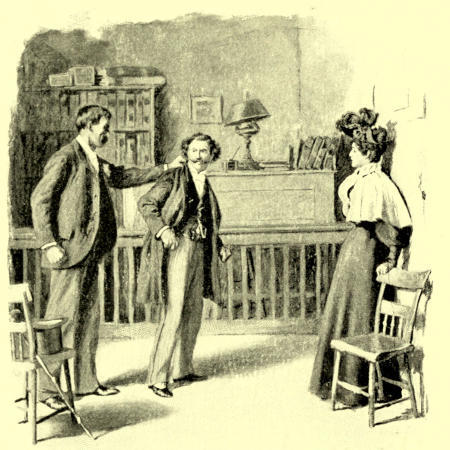

“‘HE’S SCARED NOW, THE COWARD’”

There was a pause the length of a heart-beat, and then the hated tones, shrill with fear: “I wasn’t going to the window! I wasn’t going to speak—”

“See here,” the officer’s iron-cold accents interrupted, “let us understand each other. Rosenbaum hates you, and good reason, too; he’d much rather have you dead than alive; and you ought to know that I wouldn’t mind killing you any more than I mind killing a rat. Give me a good excuse—pull that pop you have in your inside pocket just a little bit—and you’re a stiff one, sure! See?”

Again the pause, then a sullen voice: “Yes, damn you! I see. Say, won’t you let me say good-bye to my girl?”

Abbie clinched her finger-nails into her hands during the pause that followed. Wickliff’s reply was a surprise; he said, musingly, “Got any money out of her, I wonder?”

“I swear to God not a red cent!” cried the conjurer, vehemently.

“Oh, you are a scoundrel, and no mistake,” laughed Wickliff. “That settles it; you have! Well, I’ll call her—Oh, Miss Courtlandt!”—he elevated his soft tones to a roaring bellow—“please excuse my calling you, and step out here! Or we’ll go in there.”

“If it’s anything private, you’ll excuse me,” interposed a mild voice at her elbow; and when she turned her head, behold a view of the skirts of the minister of justice as he slammed a door behind him!

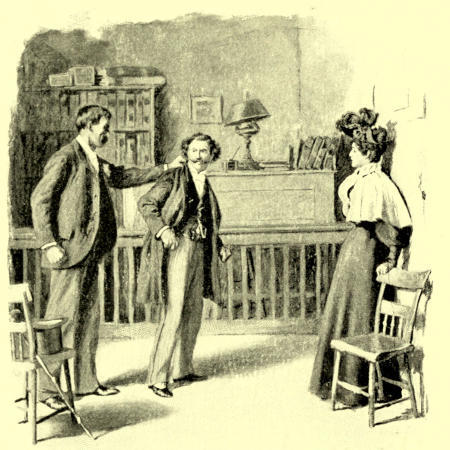

A second later, Wickliff entered, propelling Slater by the shoulder.

“Ah! Squire stepped out a moment, has he?” said the officer, blandly. “Well, that makes it awkward, but I may as well tell you, madam, with deep regret, that this man here is a professional swindler, who is most likely a bigamist as well, and he has done enough mischief for a dozen, in his life. I’m taking him to Canada now for a particularly bad case of hypnotic influence and swindling, etc. Has he got any money out of you?” As he spoke he fixed his eyes on her. “Don’t be afraid if he has hypnotized you; he won’t try those games before me. Kindly turn your back on the lady, Johnny.” (As he spoke he wheeled the fortune-teller round with no gentle hand.) “He has? How much?”

It was strange that she should no longer feel afraid of the man; but his face, as he cowered under the heavy grasp of the officer, braced her courage. “He has five hundred dollars I gave him this morning,” she cried; “but he may keep it if he will only let me go. I don’t want to marry him!”

“Of course you don’t, a lady like you! He’s done the same game with nice ladies before. Keep your head square, Johnny, or I’ll give your neck a twist! And as to the money, you’ll march out with me to the other room, and you’ll fish it out, and the lady will kindly allow you fifty dollars of it for your tobacco while you’re in jail in Canada. That’s enough, Miss Courtlandt—more would be wasted—and if he doesn’t be quick and civil, I’ll act as his valet.”

The fortune-teller wheeled half round in an excess of passion, his fingers crooked on their way to his hip pocket; then his eye ran to the officer, who had simply doubled his fist and was looking at the other man’s neck. Instinctively Slater ducked his head; his hand dropped.

“No, no, please,” Miss Courtlandt pleaded; “let him keep it, if he will only go away.”

“Beg pardon, miss,” returned the inflexible Wickliff, “you’re only encouraging him in bad ways. Step, Johnny.”

“If you’ll let me have that five hundred,” cried Slater, “I’ll promise to go with you, though you know I have the legal right to stay.”

“You’ll go with me as far as you have to, and no farther, promise or no promise,” said Wickliff, equably. “You’re a liar from Wayback! And I’m letting you keep that revolver a little while so you may give me a chance to kill you. Step, now!”

Slater ground his teeth, but he walked out of the room.

“At least, give him a hundred dollars!” begged Miss Courtlandt as the door closed. In a moment it opened again, and the two re-entered. Slater’s wrists were in handcuffs; nevertheless, he had reassumed a trifle of his old jaunty bearing, and he bowed politely to Abbie, proffering her a roll of bills. “There are four hundred there, Miss Courtlandt,” said he. “I am much obliged to you for your generosity, and I assure you I will never bother you again.” He made a motion that she knew, with his shackled hands. “You are quite free from me,” said he; “and, after all, you will consider that it was only the money you lost from me. I always treated you with respect, and to-day was the only day I ever made bold to speak of you or to you by your given name. Good-bye, Miss Courtlandt; you’re a real lady, and I’ll tell you now it was all a fake about the spirits. I guess there are real spirits and real mediums, but they didn’t any of ’em ever fool with me. Good-afternoon, ma’am.”

“‘I’LL ACT AS HIS VALET’”

Abigail took the notes mechanically; he had turned and was at the door before she spoke. “God forgive you!” said she. “Good-bye.”

“That was a decent speech, Marker,” said Wickliff, “and you’ll see I’ll treat you decent on the way. Good-morning, Miss Courtlandt. I needn’t say, I guess, that no one will know anything of this little matter from the squire or me, not even the squire’s wife. I ’ain’t got one. I wish you good-morning, ma’am. No, ma’am”—as she made a hurried motion of the money towards him—“I shall get a large reward; don’t think of it, ma’am. But if you felt like doing the civil thing to the squire, a box of cigars is what any gentleman is proud to receive from a lady, and I should recommend leaving the brand to the best cigar-store you know. Good-morning, ma’am.”

Barely were the footsteps out of the hall when the worthy justice, very red and dusty, bounced out of the closet. “Excuse me,” gasped he, “but I couldn’t stand it a minute longer! Sit down, Miss Courtlandt; and don’t, please, think of fainting, miss, for I’m nearly smothered myself!” He bustled to the water-cooler, and proffered water, dripping over a tin cup on to Abbie’s hands and gown; and he explained, with that air of intimate friendliness which is a part of the American’s mental furniture, “I thought it better to let Wickliff persuade him by himself. He is a remarkable man, Amos Wickliff; I don’t suppose there’s a special officer west of the Mississippi is his equal for arresting bad cases. And do you know, ma’am, he never was after this Marker. Just come here on a friendly visit to the chief of police. All he knew of Marker was from the newspapers; he had been reading the letter of the man Marker swindled in Canada, and his offer of a reward for him. Marker’s picture was in it, and a description of his hair and all his looks, and Wickliff just picked him out from that. I call that pretty smart, picking up a man from his picture in a newspaper. Why, I”—he assumed a modest expression, but glowed with pride—“I have had my picture in the paper, and my wife didn’t know it. Yes, ma’am, Wickliff is at the head of the profession, and no mistake! Didn’t have a sign of a warrant. Just jumped on the job; telegraphed for a warrant to meet him at Toronto.”

“But will he take him safely to Canada?” stammered Miss Abigail.

“Not a doubt of it,” said the justice. And it may be mentioned here that his prediction came true. Wickliff sent a telegram the next day to the chief of police, announcing his safe arrival.

Miss Courtlandt went to Chicago by the evening train. She is a happier woman, and her family often say, “How nice Abbie is growing!” She has never seen the justice since; but when his daughter was married the whole connection marvelled and admired over a trunk of silver that came to the bride—“From one to whom her father was kind.”

The only comment that the justice made was to his wife: “Yes, my dear, you’re right; it is a woman, a lady; but if you knew all about it, how I never saw her but the once, and all, you wouldn’t mind Bessie’s taking it. She was a nice lady, and I’m glad to have obliged her. But it really ought to go to another man.”