MAXIMS AND MINIMS

KINSPRITS

You know how it is: there are books that magically convey a secret subtle intimation that you are the only reader who has ever, will ever, wholly grasp their elusive wit and charm. So it is with certain people. I think of my friend Pausanias. He is quiet, shy; he makes his points so demurely, so quaintly, that you sometimes think, sadly, of all the occult little japes he may be making in the weeks that elapse when you don’t see him ... and no one, perhaps, “gets” them. Folly, of course—and yet I have seen his eye widen and brighten as it caught mine across the dinner table, and I knew that he and I, secretly, had both caught some faint, delicious savour of absurdity and human queerness—something that no one else there (I strongly believed it) had quite so sharply tasted. Yes, you can catch his eye—no word is necessary. Just a slow, enjoying, gentle grin. Across the great clamour of blurb and bunk, across the huge muddle of beauty, weariness, and frustration that makes up our daily life—I am always catching his eye.

* * * * *

JOURNALISM AND LITERATURE

Art is the only human power that can make life stand still. Each of us, desperately clutching his identity amid the impalpable onward pour of Time and Thought, finds only in art—and chiefly in written art—a means to halt that ceaseless cruel drift. Literature was invented to halt life, to hold it still for us to examine and admire.

Here you may see the essential distinction between literature and journalism. For journalism was devised to hurry life on even faster, to give the already whirling wheel an insane accelerating fillip. Journalism is, actually, a pastime; literature, a stoptime. I refer, of course, not to the journalism of facts, which is a department of government rather than of letters; but to the journalism of fancy. In great books life (however troubled and violent in itself) stands pure and unvexed, unfretted by time and interruption.

There are many schools of journalism; for journalism, being only a hasty knack, can readily be taught. There are no schools of literature, for that is born in your own hearts only, and by manifold joys and disgusts. If it is in you, you shall know; the disease will grow more and more potent. If it is in you, you shall be dedicated to misery unguessed by the easy minds beside you. A great poet spoke of hovering between two worlds, one dead, one powerless to be born. That shall be your mental lot. You shall realize, more and more, that the bustling cheery life of the general is, in some seizures, dead to your spirit: and yet that new brave world of imagination, which travails in your heart, can never quite come to paper. Would you know the mood and emotion that move behind literature, read Arnold’s Scholar Gipsy. I love journalism and honour it; but it must be added that it inhabits a different world from literature, and does not even faintly understand the language that literature speaks.

* * * * *

HOBBES

There are some famous books which are the delight of scholars but hardly at all known to the amateur reader. Of such, we think of Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan. It is so nobly sagacious and entertaining that with a little trouble spent on rephrasing his stuff and giving it snappy captions we could probably sell it to a long chain of newspapers and enter into competition with the Syndicated Spinozas who prey upon the public appetite for aphorisms.

Hobbes’ wisdom is of the shrewd and nipping sort. If we had to choose but one passage, to show a seventeenth-century mind at its best, we should pluck his remarks on Laughter—famous indeed, but probably little known to casual readers. See the clear stream of the mind flowing in a channel of granite prose:—

Sudden glory is the passion which maketh those grimaces called laughter; and is caused either by some sudden act of their own that pleaseth them, or by the apprehension of some deformed thing in another by comparison whereof they suddenly applaud themselves. And it is incident most to them that are conscious of the fewest abilities in themselves: who are forced to keep themselves in their own favour by observing the imperfections of other men. And therefore much laughter at the defects of others is a sign of pusillanimity. For of great minds one of the proper works is to help and free others from scorn, and compare themselves only with the most able.

On the contrary, sudden dejection is the passion that causeth weeping, and is caused by such accidents as suddenly take away some vehement hope or some prop of their power; and they are most subject to it that rely principally on helps external, such as are women and children. Therefore some weep for the loss of friends, others for their unkindness, others for the sudden stop made to their thoughts of revenge by reconciliation. But in all cases, both laughter and weeping are sudden motions, custom taking them both away. For no man laughs at old jests, or weeps for an old calamity.

The vain-glory which consisteth in the feigning or supposing of abilities in ourselves which we know are not is most incident to young men, and nourished by the histories or fictions of gallant persons, and is corrected oftentimes by age and employment.

* * * * *

LADIES AT THE PHONE

There is a certain department store on the slope of Murray Hill which has in it a gallery much frequented by ladies for meeting their friends. Once in a while we have an appointment there to wait for Titania, and always we find it an entertaining corner of the world. Along one side of the gallery is a long line of telephone booths, and we know nothing more amusing than to stroll past the glass doors, with apparently abstracted and meditative air, to watch the faces of the fair captives within. How admirable a contrivance is the feminine face for reflecting the emotions! Some you will see talking animatedly, with bright colour, sparkling eyes, every appearance of mirth and merry cheer. Others are waiting, all anguish and grievance, for some dilatory connection; their small brows heavy with perplexity. Often it seems to be necessary, for some mysterious sharing of secrets or shopping plans, for two ladies to occupy the same booth at a time; how they do it we cannot guess; but they sit demurely squeezed upon one another and their faces appear side by side, both apparently talking at once into the receiver. Through the glass pane this offers a curious sight, apparently a lady with two heads; muffled by the barrier, shrill squeaks and conjectures are dimly heard. There are ladies, generous of physique, who find it hard enough to press in singly; when they seek to arise they are held tightly by the cage and a great wrench and backing outward are necessary. Particularly on a Saturday, shortly before matinée time, are these lively creatures full of animation and derring-do. A gay and vivid panorama of human frailty, only surpassed in quaint absurdity by a similar row of men in the phone booths of a large cigar store.

* * * * *

OF STREET CLEANING

(By Our Own Lord Bacon)

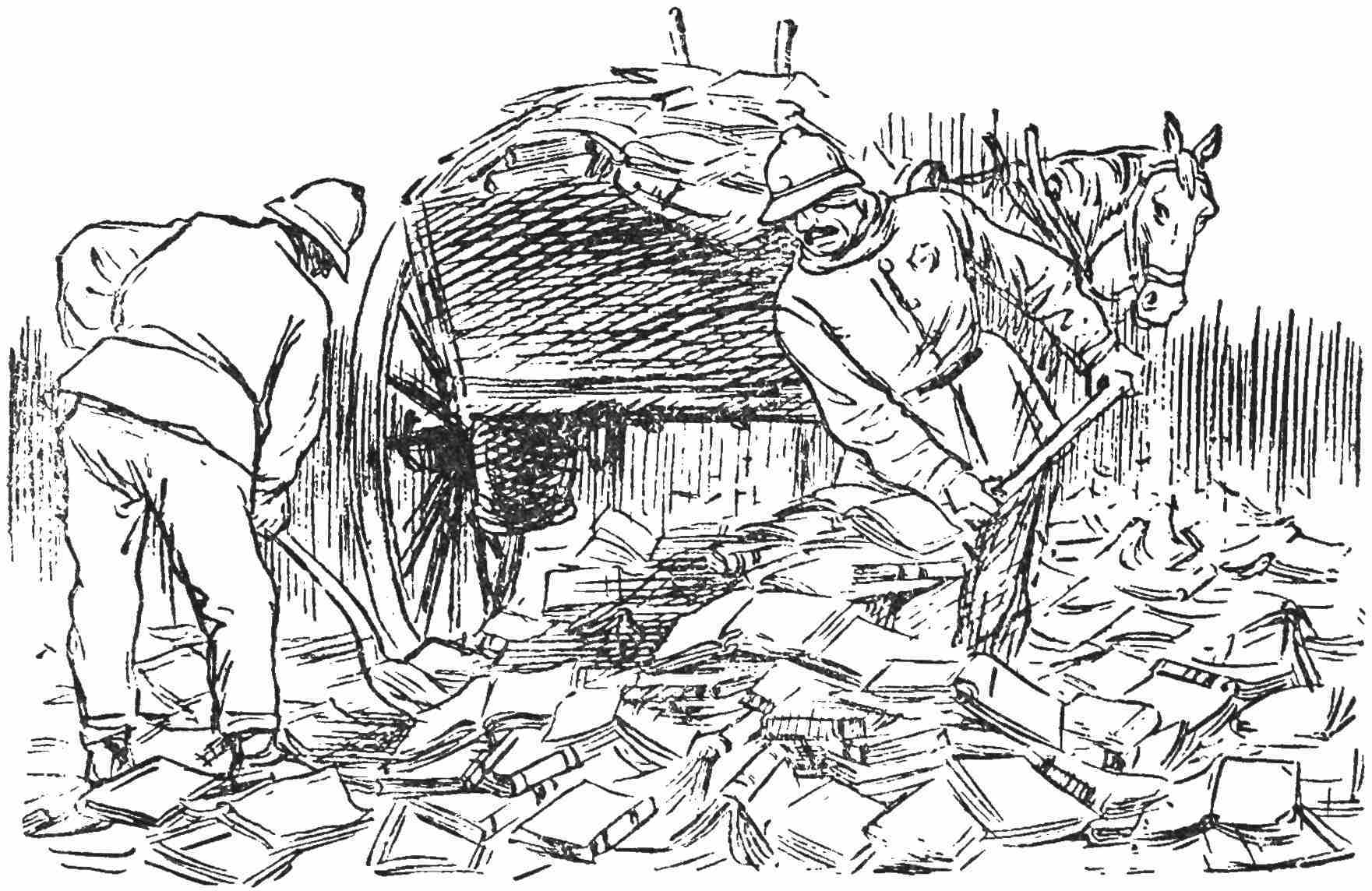

Snow is a deposit fair in itself, but a shrewd thing in a city. Where ways be crowded and traffic insisteth, let there be alacrity and stirring on the part of the city servants, lest the public have occasion of murmuring. Of streets which need purifying, there be three kinds: as Broadway, which is treacle; Fifth Avenue, syrup; and uptown, which is soup and all manner of beastliness. So also of snow there be three sorts, the dry and powdery; the wet and slushy, liquefying soon; the granular and sleety, whereof the latter adhereth long and occasioneth sudden prostrations, unwholesome to human dignity but opportunity of sport to the vulgar. When men are checked in their desires to pass to and fro without let or stoppage, then must the prince be wary to reason with the commuters, who being ever great self-lovers, sui amantes sine rivali, are like to be disproportionate in outcry. And for the most part, the subway will be still current, but small praise accrueth thereto from citizens, sudden cattle in protest but tardy to acknowledge favour. This is not handsome. Of the surface cars I will not speak; let them be, for the occasion, as though they existed not. For though there be some talk about revival of the service when the Broadway slot be picked and scalded by hand, yet is this but vaunting and idle boast. There is no impediment in the streets but may be wrought out by resolute labour. Of block parties, flame throwers, tractors, steam-ploughs and other ingenuities, I like them not. These be but toys. Let men toil with wit and will, by pick and shovel and horse-cart. This is best for the public.

* * * * *

DR. OSLER

“In seventy or eighty years” (said Thomas Browne, M. D.) “a man may have a deep Gust of the World, know what it is, what it can afford, and what ’tis to have been a Man. Such a latitude of years may hold a considerable corner in the general Map of Time.”

Surely no modern thinker has taken a deeper gust of life or pondered more charitably over the difficult problems of the race than Sir William Osler, a true follower and kinsprit of the wise physician of Norwich. “The Old Humanities and the New Science,” his last public address (given in Oxford, May 16, 1919), was the capsheaf of that long series of writings and speakings in which Dr. Osler unlocked his generous, humane heart and gave inspiring counsel to his fellows.

It was an occasion that even the most severe brevity must describe as of happy import. Osler, a physician and a man of science, had been honoured by the presidency of the Classical Association, Great Britain’s most distinguished gathering of the men who have made the culture of the antique world their touchstone in life. And Dr. Osler, himself a keen classical student, did not permit himself merely gracious and suave messages. Pleading for a new bridal of science and the classics, in that delightful and urbane chaff which he knew so well to administer, he pointed out the barrenness of the tradition that has made the famous “More Humane Letters” of Oxford entirely neglect the workings and winnings of the science that has transformed the world. Dr. Osler, in his great career, perhaps never spoke with more convincing persuasion than when he pointed out that even in their own province of the classical tongues the modern humanists have passed over the scientific work of the ancients, as for instance in Aristotle and Lucretius.

Among men who err and are baffled, but still blunder eagerly and hopefully in the magnificent richness of the natural world, there arise ever and again such figures as Osler’s, a pride and a consolation to their comrades. Men, alas! are slow in finding the treasures that lie close about them. Dr. Osler’s essays are too little known among general readers. His all-embracing humanity, his mind packed with wisdom and beauty, his humour and his sagacious and persistent method in the conduct of a crowded life, make him a figure exceptionally helpful to contemplate. This last of his essays needs to be read not only by all educators, but by all who have any rational ideals of life, and who need, every now and then, to surmount the troubled stream of quotidian affairs and focus their visions more clearly.

No sensible man doubts that, if haste and confusion and greed do not overcome us, the world should stand to-day on the sill of a new Renaissance, a new empire of the mind, in which the old foolish antagonism of science and the so-called “humanities” will be only a vain and dusty rumour. What are “liberal” studies, one may ask? Why, surely, studies that liberate—that set the spirit free from the oppression of sordid and small motives, that stir and urge it toward generous achievement and the assistance of misfortune. When did letters arrogate to themselves the heavenly adjective belles? Are there not the belles sciences also? And is the biplane now soaring over the olive-shining Hudson any less lovely than the most precious sonnet ever anchored and flattened in persisting ink?

This essay of Dr. Osler’s shows one the pulse and heartbeat of modern science, the tender spirit of idealism that urges so much of the technical investigation of our time. In Dr. Osler, as in hundreds of other scientists less known and perhaps less gifted in public utterance, there is the union of the two Hippocratic ideals which the great Canadian physician laid before himself as his guides in life—the union of philanthropia and philotechnia—a love of humanity joined to a love of his craft.

To infect the average man with the spirit of the humanities, Dr. Osler said, is the highest aim of education. And this brilliant address of his is a crowning instance of the way in which, in his mind, the practical service of science was beautified by the liberal and imperishable spirit of classical thought.

* * * * *

THE MOST EXCITING BOOK

We have just been reading what we honestly believe is the most fascinating book in the world. It is, we must confess, very much in the vein of this modern realism, because it is written in a terse, staccato, and even abrupt style, although always well balanced. The general effect, we admit, is depressing, though that may be only our own personal reaction, because the plot is one with which we are intimately familiar. Every now and then the action rises to a climax when we think it is going to end happily after all; but then something always occurs to sadden us. Occasionally it gives us moments of gruesome suspense, followed by flashes of temporary optimism. The general technique is distinctly that of the grieving Russian prose writers, for the total effect is gloomy and grim. The critics have had nothing to say about this book, but for us it has cumulating interest.

We find we forgot to mention the title of the above volume, which is issued in very handy format, bound in limp brown leather. We mean, of course, our bank book.

* * * * *

A SUGGESTION

We have been looking over the catalogue of Coventry Patmore’s library, issued by Everard Meynell at “The Serendipity Shop,” London. The following note interested us; some of our vigorous readers, now that the wooing season is toward, may find in it a gentle technical hint:

Patmore told Dr. Garnett that during his courtship, wishing to be sure that a congeniality of taste existed between himself and Emily Andrews, he lent her Emerson’s Essays, asking her to mark the passages that most struck her, and on getting the book back was delighted to find that the marks were those which he would have made for himself.

According to Mr. Meynell’s catalogue, the copy of Emerson referred to is inscribed, in Patmore’s hand: “Emily Andrews, June 24, 1847.” Emerson’s efficacy in the rôle of Cupid may be judged from the fact that the two were married September 11, 1847.

One wonders if Patmore applied the same test before his two subsequent marriages (1864, 1881).

* * * * *

ADVICE TO YOUNG WRITERS

A gentleman asks us to give some advice to young men intending to enter journalism. Well, we would say, get a job as a sporting writer. That is where the real fun lies. Being a sporting writer is hot stuff; it keeps you out in the open air, you are respected and even admired by the least easily impressionable classes, such as policemen, car conductors, and office boys; you have immense fun inventing new ways of saying things (which is the groundwork of good literature), get a great many free meals, have your expenses paid, meet people who have high-powered cars and put them at your disposal, and your lightest word is deemed important enough to be put on a telegraph wire and flashed to the office for an EXTRA. If you write about such minor matters as war and peace, poetry, books, or the beauty of this, that, and the other, you will be hidden demurely away on an inside page and there is no particular hurry about it.

The other day at the Polo Grounds we noticed a hard-boiled fan leaving the stand after the game. As he passed out onto the field he suddenly saw the gang of reporters finishing up their stories and the instruments clattering beside them. “Gee,” he cried, “look at all the writers!” And with a real awe he turned to his companion and said: “Their stuff goes all over the world.”

We contend that Joseph Conrad, Thomas Hardy, James Branch Cabell, Joe Hergesheimer, Bernard Shaw, Rudyard Kipling, and Lord Dunsany, sitting side by side on a bench writing short stories for a wager, would not have elicited such a gust of reverent admiration from our friend.

We are not joking. You can have more fun, and get better paid for it, as a sporting reporter than in any other newspaper job. And there is in it a bigger opportunity for men of real originality.

* * * * *

A GREAT REPORTER

We have been reading—for the first time, we blush to admit—the Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, in the magnificent ten-volume edition of Boswell published by Gabriel Wells. It is the ideal book for reading on the train, and causes us to reassert that Jamie was one of the world’s greatest reporters. If we were running a newspaper we would give a copy of this book to every man on the news staff. Professor Tinker in his introduction calls it “perhaps the sprightliest book of travels in the language.” Indeed, this is Boswell in excelsis, and it warms us to note the magnificent zest and gusto and triumphant happiness that peep between all his paragraphs. Happy, happy man, he had his adored Doctor to himself; he had him, at last, actually in Scotland; they were on holiday together! “Master of the Hebridean Revels,” Tinker charmingly calls him. What an immortal touch is this, of the somewhat baffled Mrs. Boswell, who must have thought the expedition a perverse absurdity. This is on the day Johnson and Boswell left Edinburgh—

She did not seem quite easy when we left her; but away we went!

Perfect, perfect—even down to the exclamation point.

We have not got very far in the Tour—only some fifty pages—but we are drowned deep in the engulfing humour and fecund humanity of the book. What an appetite for life, what a glorious naïf curiosity! What a columnist Boswell would have made! He quotes Johnson to this effect—

I love anecdotes. I fancy mankind may come, in time, to write all aphoristically, except in narrative; grow weary of preparation, and connection, and illustration, and all those arts by which a big book is made.

Boswell, with superb dramatic instinct, unconsciously adopted the most triumphant subtlety of manœuvre. He put himself in the posture of a boob in order to draw out the characteristic good things of the great men he admired. He fished passionately for human oddity, and used any bait at all that was to hand—even himself. To see the two together on Boswell’s artfully contrived stage—Scotland, which he knew would elicit the Doctor’s most genuine humours, prejudices, shrewd manly observations—and in the bright light of a junketing adventure—ah, here is a bellyful of art. What a pair: the subtle simpleton, the simple-minded sage!

* * * * *

AN UNFAIR ADVANTAGE

Of course, it’s the oldest spoof in the world; and also it isn’t quite fair; but we felt that (for private reasons) we owed it to ourself to chaff a certain publisher friend. So we diligently typed out the first dozen or so of Shakespeare’s sonnets, and, making use of a borrowed name and address kindly lent us by a colleague, submitted them to the publisher.

We accompanied them by a pseudonymous letter which we truly think was something of a work of art, it was so amiably true to the sort of thing that publishers are accustomed to receive. We explained that these were the first of a series of 154 sonnets, and added that though many of our friends thought them good, we feared their affectionate partiality. We were submitting only a few, we said, in the hope of frank criticism from a great publishing house. If we were lucky enough to have them accepted the rest would be forthcoming; and the volume (we hoped) would be bound in red leather with very wide margins and a blank page at the front for autographing. And a good deal more innocent and hopeful meditation.

We had to wait some time for the reply—and had even begun to fear that the publisher had spotted our jape. But no—here is the answer that came:

We are sorry that after a careful consideration of your “Sonnets” we cannot make a proposal for publication. We fear that we are lacking in a real enough enthusiasm to push the book as it must be pushed to bring about any success.

We regret, too, that we cannot comply with your request to criticise the work, but it is against our policy to offer criticism on material which we cannot accept for publication. We handle so many manuscripts that we could not do the work justice, and then, too, we are diffident about offering suggestions when you may find a publisher who will like your work just as it stands. In general, however, we may say that, so far as we can judge, we thought that the work was not up to standard.

Thank you for giving us the opportunity of considering your manuscript. It is being returned to you by mail.

We now lay this before a candid world and ask our friend how much blackmail we can get out of him to refrain from publishing his identity?

Yet we admit it wasn’t quite fair. A knowledge of Shakespeare’s Sonnets is no necessary equipment for successful publishing. And some of them, if you are taken unawares, do sound a bit preposterous.

* * * * *

CARAWAY SEEDS

It seemed to us that we saw a deep significance in the fact, told by Lytton Strachey in his Queen Victoria, that the Queen’s pious governess, Lehzen, was a fanatic about caraway seeds. Mr. Strachey says:

Her passion for caraway seeds, for instance, was uncontrollable. Little bags of them came over to her from Hanover, and she sprinkled them on her bread and butter, her cabbage, and even her roast beef.

Surely throughout the whole Victorian era the attentive observer can discern the faint but pungent musk of the mild, bland, uncandid caraway. We ourself, in our early youth, crossed the trail of that seed more than once, in small cakes and patties, and instinctively revolted from it. If there is any emblem symbolic of the Victorian age, perhaps it is the caraway seed, a thing that Greenwich Village, we dare say, has never encountered even in its most enterprising tea-room. The kingdom of Victoria, we suggest, was like a grain of caraway seed; but it became a tree so vast that the fowls of the air lodged in the branches thereof.

* * * * *

BLUNT’S DIARIES

We have a fear that the two volumes of Wilfrid Scawen Blunt’s Diaries—published here last year by Alfred Knopf—are not as widely known as they should be. This is natural, for the two big volumes are expensive, but they are a mine of most interesting material. They are a liberal education in the truth quot homines tot sententiæ—in other words, that there are infinite matters of difference among honourable men.

Blunt was a gallant dissenter and whole-hearted skeptic about civilization. Of course these aristocratic rebels, who have never had to pass through the gruelling discipline of middle-class life; who have always been free to travel, to ramble about to witty week-end parties at country houses, ride blooded horses, sit up all night drinking port wine and talking brilliantly with Cabinet Ministers, have (or so it seems to us) a fairly easy time compared to the humdrum plod who wambles through a stiff continuous stint of hard work and still keeps a bit of rebellion in his heart. And of course, since Blunt condemned almost everything in European politics throughout his lifetime, one begins to suspect that he was almost too pernickety. Of the unnumbered British statesmen whom he roasted, not all can have been either fools or knaves. The law of average forbids. But a protestant of that sort is a magnificently healthy and useful person to have about. He had a habit of assuming that Egypt, India, Ireland, Turkey, Germany, were always right, and England necessarily wrong. When a country has a number of citizens like that and regards them affectionately, it is a sign that it is beginning to grow up. One of Blunt’s remarks to Margot Asquith is worth remembering: “There is nothing so demoralizing for a country as to put people in prison for their opinions.”

But the casual reader ought to have a go at Blunt’s Diaries because they are a rich deposit of pithy human anecdote. We see him, at the age of sixty-six or thereabouts, attending a performance of Hippolytus, translated by Murray. “At the end of it we were all moved to tears, and I got up and did what I never did before in a theatre, shouted for the author, whether for Euripides or Gilbert Murray I hardly knew.” With Coquelin père he goes to have lunch with Margot Asquith. Her little daughter, twelve years old (now, of course, Princess Bibesco, whose short stories are well worth your reading), dressed in a Velasquez costume, was called on to recite poems. “Coquelin good-naturedly suggested that ‘perhaps Mademoiselle would be shy,’ but Margot would not hear of it. ‘There is no shyness,’ she said, ‘in this family.’” Any lover of the human comedy will find intense joy in Blunt’s comments on Edward VII, for instance. When his antipathies were aroused, Blunt lived up to his name. Roosevelt’s speech in Cairo in 1910 praising British rule in Egypt was a red rag to the elderly skeptic, who considered that Britain had no business anywhere on earth outside her own island. His comment in his journal was: “He is a buffoon of the lowest American type, and roused the fury of young Egypt to the boiling point ... he is now at Paris airing his fooleries, and is to go to Berlin, a kind of mad dog roaming the world.” It is quaint that the humanitarians and intense lovers of their kind are always the most brutal in attack upon those with whom they disagree.

There are also innumerable snapshots of men of letters in mufti. Rossetti, for instance, throwing a cup of tea at Meredith’s face. Most of Meredith, Blunt found unreadable. His picture of Francis Thompson’s last days is unforgettable. For our own part we find particular amusement in the little sideviews of Hilaire Belloc—a neighbour in Sussex in the later years. It is disconcerting to learn that Belloc’s horse “Monster,” of whom the hilarious Hilaire speaks so highly in a number of essays, is “a very ancient mare which he rides in blinkers. He is no great horseman.” Belloc coming to picnic with a bottle of wine in his pocket; Belloc out-talking Alfred Austin, Arthur Balfour, and indeed everyone else; Belloc wondering if he would be given a peerage; Belloc groaning because he has sworn off liquor during Lent, and Belloc delightfully and extremely wrong in the days just preceding the war—insisting that Germany was unprepared and afraid of France—these are the sort of things that cannot by any stretch of exaggeration be called malicious tattle; they are the genial byplay of civilization that keeps us reminded that those we love and admire may be not less absurd than ourselves.

There is much real beauty in the book, too. Blunt was a poet of very considerable charm, and a little story told by a former schoolmate of his seems rather characteristic. When a child he used to keep caterpillars in paper boxes; but he always pricked holes in the lids in the form of the constellations—so that the imprisoned caterpillars might think they were still out of doors and could see the stars.

It’s a queer thing. Those caterpillars, somehow or other, make us think of newspaper men.

* * * * *

GENIUS

Occasionally we have fired off a culverin or two in honour of Stella Benson, that remarkably agile and humorous creature, who is, with May Sinclair and “Elizabeth,” one of our favourite female novelists. So we are particularly pleased to have F. H. P. recall to us a passage about the Dog David, in Living Alone:

David Blessing Brown, a dog of independent yet loving habit, had spent about four-fifths of his life in the Brown family. He was three years old and though ineligible for military service made a point of wearing khaki about his face and in a symmetrical heart-shaped spot near his tail. To Sarah Brown he was the Question and the Answer, his presence was a constant playtime for her mind; so well was he loved that he seemed to her to move in a little mist and glamour of love....

I believe that Sarah Brown had loved the Dog David so much that she had given him a soul. Certainly other dogs did not care for him. David said that they had found out that his second name was Blessing and that they laughed at him for it. His face was seamed with the scars of their laughing. But I know that the enmity had a more fundamental reason than that. I know that when men speak with the tongues of angels they are shunned and hated by men, and so I think that when dogs approach humanity too nearly they are banished from the love of their own kind.

If you do not recognize, even in that little random passage, the curious quality of Stella Benson’s talent, then we fear (brave friends) we can never agree about literature. In her writing we always seem to see that special and bewildering richness that we prize most of all; something that does not lie in any particular nicety or adornment of words, but in an underrunning flavour and queer subtlety of meaning. Is there any subject in the world more trite, more shopworn, and defaced by acres of blab than Dogs and their relations to mankind? There is not. And yet see how Stella Benson, without one pompous or pretentious word, and with a humour both mocking and tender, has not only said something new, but something which, as soon as it is said, becomes old, because it is permanent. That is what, in lieu of a better word, we are inclined to call genius, and we have never read a page of Miss Benson’s wo