CHAPTER X

Seven years afterward, Toni found himself one day at the little town of Beaupré, in the valley of the Seine, where the circus was performing, for Toni had remained with it all that time. Beautiful young ladies in spangles had come and gone, demigods in red satin with white sashes had done the same. Toni himself was a demigod in red satin and a white sash, and was the crack rider of the circus. He had a large head-line of letters a foot high all to himself—Monsieur Louis D’Argens he was called on the bill-boards, although everybody about the circus called him Toni. Toni was then twenty years old and at least twenty years wiser than he had been seven years before. One does not spend seven years in the circus without learning many things. He learned all the immense wickednesses as well as the immense virtues which may be found in the lower half of humanity.

But, like most demigods, Toni was not happy. Perhaps it was a part of the general quarrel which every human being has with fate. But Toni’s principal quarrel was that he was haunted with fears of all sorts. This madcap fellow, this daring bareback rider, this centaur of a man, to whom nothing in the shape of horseflesh could cause the slightest tremor, who could ride four horses at once and could do a great many other things requiring vast physical courage, coolness and resolution, was, morally, as great a coward as he had been in the old days when he ran away from all the boys in Bienville except Paul Verney, and ran away from home rather than face his mother after having taken a single franc. He was mortally afraid of a number of persons: of Clery, the tailor in far-off Bienville, for fear he might set the police on him; of Nicolas, who had the upper hand of him completely, and of a friend of Nicolas’, Pierre by name, who was the most complete scoundrel unhung except Nicolas himself. Both of these two men Toni could have whipped with one hand tied behind his back, for he was unusually muscular and, though somewhat short, a perfect athlete. His two scampish friends, Nicolas and Pierre, were wretched objects physically, such as men become who are born and bred in the slums, who have behind them a half-starved ancestry going back five hundred years, and who are on intimate terms with the devil. For a circus rider may practise every one of the seven deadly sins with perfect impunity except one, that of drunkenness. A circus rider must be sober.

They had drawn Toni into many a scrape, but here again Toni’s strange cowardice had saved him from taking an actual part in any wrong-doing. He watched out for Nicolas and Pierre, at their bidding, he knew of their wrong-doing, where they kept their stolen gains, how they cheated the manager, how they abused the women. But Toni himself, although the associate of two such rogues and rascals, and in many ways their blind tool, had kept himself perfectly free from the commission of any crime or misdemeanor. His heart remained good—poor Toni!

He still hankered, mother-sick, for Madame Marcel. Once every year since he had run away he had written to her as well as he could, for Toni’s literary accomplishments were very meager, a letter all tear-stained, telling her he was well and trying to behave himself, and he hoped she did not have rheumatism in her knees and that he was sorry for having stolen the franc. He even sent her a little money once a year, which Madame Marcel did not need, but which Toni did, and in these letters he always sent his love to Denise, but he never gave his address nor any clue to his employment. He was afraid to give any address for her to answer his letter, and so did not really know whether his mother were alive or dead.

His heart still yearned unceasingly after Paul Verney, the friend of his boyhood; and none of the young ladies in tights and spangles had been able to put out of his mind little Denise in her blue-checked apron, and her plait of yellow hair hanging down her back, and her downcast eyes and sweet way of speaking his name. He never heard the church-bells ringing on a Sunday morning that his Bienville Sundays did not come back to him—his mother washing and dressing him for church; the sight of Denise, in her short white frock, trotting along solemnly with her hand in Mademoiselle Duval’s; Paul Verney smartly dressed and hanging on to his father’s arm; Madame Ravenel, in her black gown, standing just inside the church door, with Captain Ravenel, grave and stern-looking, standing outside—and then the world in which Toni lived seemed like a dream, and this dream of Bienville the only solid reality.

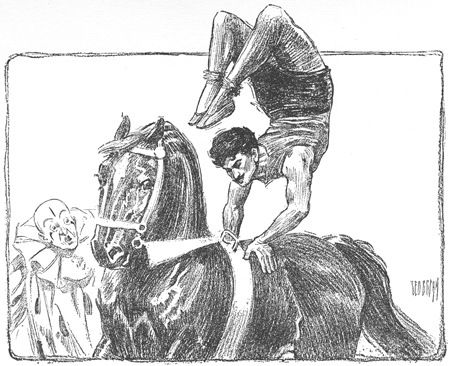

One friend remained to him, the ever-faithful Jacques, now battered almost beyond the semblance of a soldier. Toni continued his friendship for horses. Half of his success with them came from the perfect understanding of a horse’s heart and soul which Toni possessed. The other half came from that strange and total absence of fear where actual danger was concerned. When the circus tent caught fire in the midst of a crowded performance, Toni was the calmest and most self-possessed person there, and careered around the ring doing his specialty, a wonderful vaulting and tumbling act, while the canvas roof overhead was blazing and no one but himself saw it. When the bridge broke through, with the circus train upon it, Toni was the first man to pull off his clothes and jump into the water, and assisted in saving half a dozen lives. He was regarded somewhat as a hero and daredevil, while secretly he knew himself to be the greatest coward on the face of the earth. Nicolas and Pierre knew this weakness of Toni’s from the beginning and traded on it most successfully.

“Doing his specialty, a wonderful vaulting and tumbling act.”

The company was performing in the fields outside of Beaupré, but as they were playing a whole week’s engagement in the town, some of them were quartered in the little hamlet close by. Within sight of the hamlet’s church-spire was a beautiful château standing all white and glistening in the sunlight, surrounded by prim and beautiful gardens watched over by sylvan deities in marble. On the broad terrace a fountain plashed, and lower down a beautifully-wooded park stretched out. Over the stone gateway leading into the park were the words “Château Bernard.”

The first time Toni saw this was when he was on his way to the midday performance in the town of Beaupré. He stopped, and the meaning of that name flashed into his mind in a second. Little Lucie, that charming little fairy whom Paul Verney loved so much, and of whom he had confided, blushingly and stumblingly, some things to Toni in those far-off days at Bienville, seven years before, when he and Paul had sat cuddled together on the abutment of the bridge,—the sight of the name “Château Bernard” brought all this back to Toni.

It was a beautiful, bright spring morning, like those mornings at Bienville, except that to Toni the sun never shone so brightly anywhere as it had shone at Bienville. He stopped and gazed long at the château, his black eyes as soft and sparkling as ever they had been, although now he was a man grown. But there was an eternal boyishness about him of which he could no more get rid than he could cease to be Toni. There had not been a day in all the years since he left Bienville that he had not thought of Paul Verney, and thinking of Paul would naturally bring to his mind the beautiful little Lucie who was like a dream maiden to him—not at all like Denise, who was to him a substantial though charming creature. He reckoned that Lucie must be now twenty, and Paul must be a sublieutenant.

As Toni stood there, his arms crossed, and leaning on the stone wall, he heard the clatter of horses’ hoofs, and down the avenue came three riders, a young girl and her escort in front and a groom behind. As they dashed past Toni, he recognized, in the slight, willowy figure in the close-fitting black habit and coquettish hat, Lucie Bernard, a young lady now, but the same beautiful, joyous sprite she had been ten years before in the park at Bienville. The cavalier riding with her was, like Toni, below middle size, but, unlike Toni, light-haired and blue-eyed, not handsome, but better than handsome—manly, intelligent, clear of eye, firm of seat, full of life and energy, and with an unstained youth. It was—it was—Paul Verney.

As the two flashed past, followed by the groom, Toni almost cried aloud in his agony of joy and pain, but he dared not run after them and call to them. They, of course, knew that he had run away from Bienville because he was a thief. That theft of a franc was perpetually gnawing at Toni’s heart. The sight of Paul Verney seemed to show him the gulf between them. Toni stood, leaning on the wall, his head hanging down, his mind and soul in a tumult, for a long time, until presently the sound of a clock striking through the open window of the keeper’s house aroused him to the knowledge that it was almost time for the circus to begin. He ran nearly all the way to Beaupré, for he worked as honestly at his trade of a circus rider—only it did not seem like work to Toni—as Paul Verney did at his as a sublieutenant of cavalry.

But all that day, through the performance, during the intermission, and at the afternoon performance and in the evening, when Toni went back to his little lodging in the village, the vision haunted him. Lucie and Paul looked so young, so happy, so fresh, so innocent! They had not behind them anything terrifying. Neither one of them had ever stolen anything, unless it was the other’s heart. They had no Nicolas and Pierre to make them stand watch while thefts were being committed—to make them lie in order to shield rascally proceedings—always to be threatening them with exposure.

Toni was so tormented by these thoughts that he lay on his hard little bed in his garret lodging, wide-awake, until midnight and then he was roused from his first light sleep by a pebble thrown at his window. Toni waked, started up in his bed and shuddered. That was the sign that Nicolas and Pierre wanted him. They were his masters; he knew it and they knew it. He got up obediently, however, slipped on his clothes, and went down the narrow stair noiselessly. Outside were his two friends.

“Come along,” said Nicolas.

“Where are you going?” weakly asked Toni.

“We will tell you when we get there,” replied Pierre, with a grin.

There was no moon, and the night was warm and sultry, although it was only May. Toni followed his two friends along the highroad. Nicolas and Pierre spoke to each other in low voices, and Toni easily made out that they were engaged on a scheme of robbery. At that his soul turned sick with horror. He had never robbed anybody of a single centime except that one solitary franc which he had taken from his mother, but he knew more about robberies than most people. The bare thought of them always frightened him inexpressibly, but he continued trudging along without making any protest.

Presently they came to the stone wall around the park of the Château Bernard, over which they all scrambled and made straight for the château. Everything was quiet about it and apparently every one was asleep, except in one room on the ground floor. There were some gigantic, luxuriant lilac bushes, now in all their glory of bloom and perfume, and under these the three crept. Never again could Toni smell the lilac blooms without being overcome by a sickening recollection. The window was open, and within the small and luxuriously-furnished room they could see an old lady, very splendidly dressed, and a man of middle age. Toni at once recognized her from the description which Paul and Lucie had given him so many years before. Madame Bernard was very large, tall and handsome, and sterner in aspect than both old Marie, who sat by the monument at Bienville, and the monument itself. She was by far the grandest-looking person Toni had ever seen, and he did not suspect that she was as great a coward in her way as he was in his. Courage is a very variable quantity and subject to mysterious ebbs and tides.

Some gold and bank-notes were on a table before them, and the old lady was saying, weeping a little as she spoke:

“I think you have behaved to me most cruelly, Count Delorme. Whatever Sophie’s faults were, you got, at least, the benefit of her entire fortune, which you squandered in your five years of marriage. Now you come here, when my little Lucie is at an age to be damaged by raking up this old story about Sophie, although you promised me, if I would give you two thousand francs a year, that you would never show yourself in this part of the country.”

“I am obliged to show myself,” responded Delorme, a thin-lipped, hawk-eyed man, who looked the villain he was. “What are two thousand francs a year? My cigars cost me almost as much as that. And as for Sophie’s fortune—well, a woman like that was dear at any price. If I had not got it, Ravenel would, and I should not think that you would be particularly proud of him as a grandson-in-law.”

“I am not,” responded old Madame Bernard weakly, and then summoning something of dignity, added, “but I venture to say that he is a better man than you are, Count Delorme. At least, he has been far more considerate of the feelings of Sophie’s family, and has kept himself and her in the strictest seclusion, nor have they asked me for a franc. I think, also, that the Ravenels still have many friends, while I am not aware of a single one that you have, Count Delorme.”

In answer to this, Delorme coolly picked up the notes and money, and, without counting either, stuffed them in his pocket. Madame Bernard made a faint protest. “There is much more there,” she cried, “than two thousand francs. I did not mean to give you all.” But Delorme, rising and taking his hat, walked out of the room, and let himself out of the house by a small side door.

Toni knew then what his friends were up to. The three followed Delorme through the park, Toni lagging behind. Presently, in a dark place overhung by a clump of cedars, they came upon Delorme, who had every vice except that of cowardice. He turned on them and said, in a threatening voice:

“What do you mean by following me, fellows?”

For answer, Pierre and Nicolas fell upon him, Nicolas striking him a violent blow on the head with a short, loaded cudgel. Delorme fell over without a word, and in a minute his pockets were rifled. Toni stood by, dazed and unable to move. It was all over in less than two minutes, and the three were running away as fast as they could. Toni knew that Delorme was dead, lying in the roadway in the dark, his face turned upward toward the night sky, himself robbed of the money of which he had robbed Madame Bernard.