CHAPTER XI

Next morning, by daylight, the whole region was aroused. Count Delorme had been found dead, robbed and murdered, in the park of the Château Bernard. The police appeared in swarms. No one had seen him at the château, and old Madame Bernard had fainted when told of the murdered man being found in the park, and had taken to her bed very ill, so she could not be disturbed. Delorme’s identity was easily established, and it was surmised that he was on his way to the château when he had met his fate.

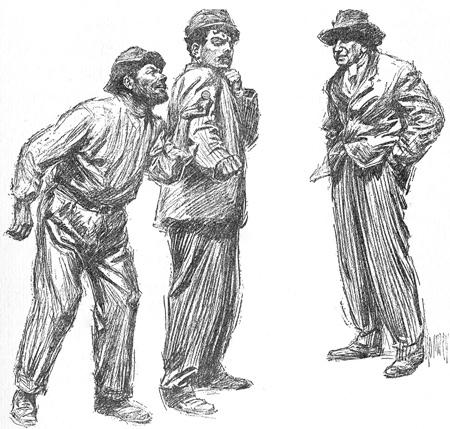

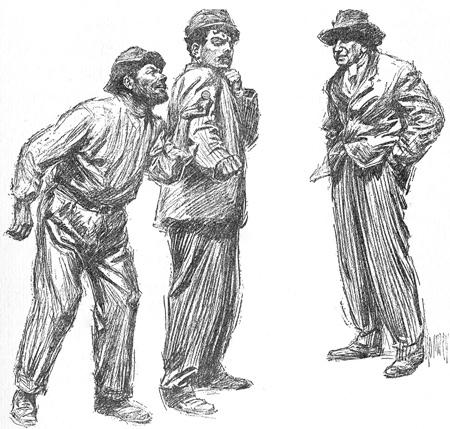

Toni listened, with a blanched face, to all the excited talk and colloquy that went on among the villagers as well as the circus people about the strange murder. Suspicion at once fell on the circus people, but Pierre and Nicolas were old hands at the business and knew how to manage such little affairs. They had promptly proceeded, the first thing next morning, to try for an advance of money from the manager of the circus, and being refused, they had tried to borrow money from several of their fellow employees to disguise the fact that their pockets were well-lined at that very moment with Delorme’s money. Toni had never thought of this subterfuge, and did not attempt to borrow a franc. He spent the day in one long spasm of terror, and in the evening, when the performance was over and he was going back to his lodging, his two friends joined him.

“Toni,” said Nicolas, with a laughing devil in his eye as he spoke, “you must be very careful, for suspicion might fall on you for the part you took in our little escapade. You struck the blow, you know.”

Toni stopped, stared, and threw his arms up above his head in a wild passion of despair.

“I did not—I did not—I did not,” he cried.

Then Nicolas, slipping his hand in Toni’s pocket, drew out a twenty-franc gold piece, a coin which Toni had seldom in his life owned.

“‘This is what you took out of the man’s pocket.’”

“This was what you took out of the man’s pocket,” said Pierre. It was too much for Toni. They were walking along the highway toward the village, in the soft May evening. Toni, quite unsteady on his legs, sat down by the roadside. He was so stunned and dazed that he could neither move nor think nor speak. Pierre and Nicolas walked off laughing, Pierre, meanwhile having put the twenty-franc piece in Toni’s pocket. When Toni felt this, he threw the money after them frantically, and it fell in the road behind them, but they did not see it. Toni, without knowing this at the time, thereby accomplished a stroke of justice to these wretches.

He sat there a long time after his two friends had left him. Presently the power of thought returned to him, and he said to himself:

“Toni, here is another terrible secret for you to carry—heavier than any yet that you have carried—too heavy for you to carry alone. Toni, you are a coward. If you were not, you would have got away from Nicolas and Pierre a long time ago. Now see what they have led you into. Toni, you must go to Paul Verney and make a clean breast of it, otherwise, you will live to be guillotined.”

He had no friend to whom he could go for counsel, unless he could find Paul Verney. He took Jacques out of his pocket, and Jacques looked at him in a friendly way and agreed with him as he always did, saying:

“Toni, unless you take some steps you will certainly be guillotined or sent to prison for life; so make up your mind to find Paul Verney and tell him all about it.”

Toni took this resolution, but the courage which inspired him to make it did not inspire him, at once, to carry it into effect. He meant to do it the first thing next day, but when the next morning came he put it off until the afternoon, and when the afternoon came he again delayed. A secret like that is frightful to keep and more frightful to tell. And then suddenly their week was up at Beaupré.

After leaving Beaupré, they gave performances in the small towns round about. Interest in the murder of Delorme had by no means died out, but rather increased as time passed on and no clue to the murderer was discovered. Toni had an instinctive feeling that the police were watching the circus people. He felt that every one of them was under suspicion, but he had no tangible proof of this. It made him long, however, to get away from the circus. He knew that he was of an age when his army service might begin at any moment, as his twentieth birthday was close at hand. He had, in fact, already been served with notice. He could have got off, being the only son of a widowed mother, but it had occurred to him that by serving his time in the army he might get rid, for a while, of his two friends, Nicolas and Pierre. A dream came to him that after his service he would get a place as teacher in a riding-school. Then he would still have horses for his friends and companions, but there would be nothing of Nicolas and Pierre in his life. The dream grew brighter the more he dwelt on it. He would go back to Bienville and ask his mother’s pardon, which he had done in every letter that he had written her, and then she would forgive him. And he would make her ask for the hand of Denise for his wife.

Oh, how happy he could be if only he had not this terrible secret about Count Delorme to carry, which stayed with him day and night. If he could get away from the circus, he thought this secret might then be less terrible to bear. The first step toward this was soon accomplished by the strong arm of the law, because Toni found himself, one June morning, drawn in the conscription. He had no thought of getting off, because he was his mother’s only son, and presently he found, to his immense joy, that he was to be one of the number of recruits who were to report at the cavalry depot at Beaupré.

Beaupré was like Bienville in one way, having a small garrison and being a cavalry depot, but it was new and modern, unlike Bienville. Although quite as bright, the barracks and stables were all new and shining with fresh paint. And oh, what joy was Toni’s when he recalled that Paul Verney was stationed there! It seemed to him as if what is called the good God, who had neglected and forgotten him for seven whole years, had at last relented and was directing his destiny and showing him the path to peace.

It was almost two months after Toni’s little adventure in the park of the Château Bernard that, one morning, Sergeant Duval, the father of Denise, heaved a heavy sigh as he paced the tan-bark in the riding-school at Beaupré and mournfully surveyed the group of recruits who were to take their first lesson in voltige or circus riding. There were about fifty of them. They all came from Paris, and recruits from Paris are notoriously hard to break in. They feel a profound contempt for the “rurals,” a term which they apply to everybody outside of Paris. The sergeant, running his eye over them, had no difficulty in sorting them out, so to speak, according to their different degrees of incapacity. About half were clerks, waiters, and artisans’ apprentices, town-bred and certain never to get over their fear and respect for horses. The other half were porters and laborers and the like, who could be taught to stick on a horse’s back, but would never acquire any style in riding.

Among them was a stupid-looking young fellow, rather short but well-made, with very black eyes and a closely-cropped black poll, whom Sergeant Duval did not recognize in the least as his old friend Toni, the unknown aspirant for the hand of Denise. Toni’s apparent fear and dread in the company of the horses had kept the troopers in a roar of laughter ever since he had joined. His awkwardness in the simple riding lesson of the day before showed what a hand he would make of it in the more difficult voltige, and his companions had hustled him to the first place in the line, so they could see the fun.

Just then Sublieutenant Verney walked into the riding-hall. He was the same Paul Verney, only he was twenty-two years old, and was known and loved by every man and by every horse in the regiment. This triumph was something to be laid at the feet of Lucie Bernard, whom he had loved ever since that August afternoon in the park at Bienville, when she had taken his book away from him and his heart went with the book. Sublieutenant Verney was always present at the riding-drill, whether it was his turn or not, and he dreamed dreams in which he saw himself as another Murat or Kellerman, leading vast masses of heavy cavalry to overwhelm infantry—for he held to the French idea that men on horses can ride over men on foot. His dog, Powder, a smart little fox terrier, was at his heels.

Now Paul Verney was an especial favorite with Sergeant Duval, who had known him as boy and man, who had seen sublieutenants come and go, and knew the breed well. He looked gloomily at Paul as he came up and ran his eye casually over the recruits.

“Pretty bad lot, eh, Sergeant?” said Paul.

“Dreadful, sir. It would have broken your heart to have seen them in the riding-school yesterday. Not one of them has any more notion of riding than a bale of hay has.”

“Ah! Well, you can lick them into shape, if anybody can,” was Paul’s reply to this pessimistic remark.

The specially-trained horse on which greenhorns learned was then brought in. He was an intelligent old charger, and when he stood stock-still, with a trooper holding up his forefoot, his small, bright eye traveled over the recruits. Then, suddenly dropping his head, he gave forth a long, low whinny of disgust, which was almost human in its significance.

“Old Caporal even laughs at them!” cried the sergeant. “Now, come here, you bandy-legged son of a sailor, and get on that horse’s back, and do it with a single spring.”

This was addressed to Toni, who lurched forward so clumsily that it was seen there was little hope for him.

The waiting greenhorns watched with a sympathetic grin Toni’s timid and awkward preparations to spring on Caporal’s back. He moved back at least ten yards, and, lunging forward with the energy of despair, succeeded in landing on the horse’s crupper, from which he slid to the ground, and lay groaning as he rubbed his shins. A shout of laughter, in which every man joined except the sergeant, followed this. Even Powder gave two short, sharp yaps of amusement. The sergeant, though, was in no laughing mood.

“Now, then,” he cried, “are you going to keep us here all day? Get up and try again!—and this time, be sure and land between the horse’s ears.”

Thus adjured, Toni, still rubbing his shins, got up, and going still farther off, made another clumsy rush. This time, by scrambling with both hands and feet, he managed to get on Caporal’s back, and then, working forward, he perched himself almost astride the horse’s neck, and said with a foolish smile:

“I can’t get any farther forward, sir.”

“Get off!” roared the sergeant.

Toni worked backward as he had worked forward, and slid down behind. Old Caporal, at this, made a disdainful motion with his hind leg, and Toni, with a scream, bolted off, yelling: “Take care! take care! he’s beginning to kick.”

The recruits had something else to think of now in their own efforts to vault on Caporal’s back. Some of them were awkward enough, but all did better than Toni. Then came the mounting and dismounting while the horse was galloping round in a circle, the sergeant standing in the middle with a long whip to keep him going.

Toni, meanwhile, had stood with his heart in his mouth, watching Paul Verney. There was not, on Paul’s part, the slightest recognition of his old friend. Toni’s shock of black hair, which was as much a part of him as his black eyes and Jacques in his pocket, had been closely-cropped, and he had grown a black mustache, which quite changed the character of his face, and he looked away from Paul Verney, not wishing for recognition at that time and place.

Toni was also the first man to attempt the mounting and dismounting. He ran around the circle twice before he seemed to screw up enough courage to try to mount, and could not then until the sergeant’s long whip had tickled his legs sharply. In vain he clutched at the horse’s mane, and made ineffectual struggles. Once he fell under Caporal’s feet, and only by the horse’s intelligence escaped being trodden on.

“If the horse were as great a fool as you are,”—roared the sergeant.

Crack went the sergeant’s whip as Toni got on his legs. Timidity and stupidity have to be got out of any man who has to serve in a dragoon regiment, and the sergeant proceeded to take them out of Toni.

“Look here, my man,” he said, “you have got to learn to do that trick now and here—do you understand?”

“But, Sergeant,” moaned Toni, “I am afraid of the horse, I swear I am—”

The sergeant’s reply to this was to run toward Toni with uplifted whip. Old Caporal, supposing the whip was meant for him, suddenly broke into a furious gallop. Toni darted toward him, lighted like a bird with both feet on the horse’s back, folded his arms, stuck his right leg out as Caporal sped around the circle, changed to his left, turned a somersault, stood on his head on the horse’s back for a whole minute, and then with a “Houp-la!” flung himself backward to the ground, and, approaching the sergeant, stood calmly at attention. The roof of the riding-hall echoed with thunders of laughter and applause, Sublieutenant Verney leading off, capering in his delight, and pinching Powder to make him join his yelping to the uproar. The sergeant stood grinning with satisfaction. He was one of the few sergeants who wanted a man to ride well and cared very little what share of praise or blame accrued to himself in the doing of it.

“So you were in the circus?” he asked.

“Yes, Sergeant—ever since I was thirteen,” answered Toni, who had thrown off his stupid expression like a mask and stood up alert, cool, with a glint of a smile in his eye. Then he stopped. He had not forgotten those magnanimous offers made by the sergeant to his mother to marry her for the purpose of thrashing him. His old cowardice returned to him and he trembled at the idea of the coming recognition by the sergeant. He certainly would not consider a circus rider a match for Denise, who, by this time, must be a young lady.

The seven years which had changed Toni and Paul from boys into men, had apparently passed over the sergeant without leaving the smallest sign on him, but they had marked Toni so that Sergeant Duval so far had no idea that he was the Toni whom he had yearned to thrash.

A light had been breaking upon Paul Verney’s mind. There had been something strangely familiar in the awkward recruit. A thrill of remembrance swept over Paul Verney, but Bienville and Toni were far from his mind then, and besides, Toni, as a dirty, shock-headed boy, had been the personification of boyish grace, while this fellow had been the embodiment of awkwardness in walking as well as riding. But now things began to grow clearer. As for Toni, the old joy and love of Paul came over him with a rush. He straightened himself up, stood at attention, and turned his gaze full on the young lieutenant.

Paul came up close to him.

“Isn’t this—isn’t this Toni?” he asked.

For answer, Toni saluted and said, “Yes, sir.” He had learned enough, during his short enlistment, to say that. And then, surreptitiously opening his hand, Paul caught a glimpse of the old battered Jacques in Toni’s palm. He covered it up quickly again. Paul Verney could not trust himself with all the recruits standing by, and the riding lesson in progress, to say more than:

“Come to my quarters at twelve o’clock,”—and turned away.

Sergeant Duval then recognized Toni, and with severe disapproval.

“So you have turned up at last!” he said sternly, “while your poor mother has been breaking her heart in Bienville these seven years about you. Well, I will talk with you later. I don’t suppose you learned any good in the circus except how to ride.”

But this could not crush Toni. He had felt all his perplexities and miseries dwindle since he had spoken to Paul Verney. Paul always had such a sensible, level head, and knew well that plain, straight path out of difficulties—telling the truth and standing by the consequences.