CHAPTER XII

At Paul Verney’s quarters, therefore, on the stroke of twelve, Toni presented himself. He had laid aside his pretended awkwardness and when he stood, erect and at attention, in his dragoon uniform, he was a model of lithe and manly grace. His circus training had developed his naturally good figure, and he was as well built a young fellow as one would wish to see. He was handsome, too, in his own odd, picturesque way. His teeth were as white as ever and shone now in a happy grin, while his black eyes were full of the mingled archness and softness that had distinguished the dirty little Toni of ten years before.

Paul was as happy as Toni, and the two eyed each other with delight when they were alone. Paul stepped softly to the door and, locking it, held out his arms to Toni, and the two hugged each other as if they were ten years old, instead of being twenty and twenty-two.

“And now, Toni,” said Paul, “tell me all that you have been doing. I don’t suppose you learned anything good in the circus except riding.”

“That’s just what Sergeant Duval said to me,” replied Toni, and then the memory of all he had suffered since his association with Pierre and Nicolas came to his mind and his expressive eyes glowed.

“It is true, Pa—I mean, Lieutenant, that I got into bad company when I was in the circus, and I want to tell you all about it. But first tell me something about Bienville. I have written regularly to my mother, but I was afraid to give her my address.”

“Afraid of what?” asked Paul.

Toni’s eyes wandered around the room aimlessly, and came back to Paul’s.

“I always was afraid,” he said.

“Your mother is alive and well,” said Paul, “but heart-broken about you. What induced you, Toni, to run away as you did?”

“Because—because—” That one franc still loomed large in Toni’s mind. “I took a franc from my mother—only a single franc, to go to the circus, and Clery, the tailor, caught me and accused me of taking the money and whipped me and said he would have me arrested and then—oh, I was so frightened! I have been frightened every time I thought of that franc in these more than seven years.”

“Some story of the sort got out,” answered Paul, “but your mother always denied it. I don’t really think she missed the franc that you took out of the box. But Toni, what a fool you were—what a monumental fool you were.”

Toni shook his head. “And a coward, too, sir,” he said. It was very difficult to add that “sir” when he spoke to Paul, and equally strange for Paul to hear.

“Look here, Toni, don’t call me ‘sir’ when we are alone—I can’t stand it. As soon as we step outside in the corridor it shall be ‘my man’ and ‘sir,’ but when the door is locked we are Paul and Toni.”

Toni nodded delightedly. “It never would have worked,” he said, “when the door is locked on us.”

“I never could understand that cowardice in you,” said Paul. “You were the most timid boy I ever saw in my life about some things, and the most insensible to fear about others.”

“I know it, but the reason why you can’t understand it is because you are not afraid of anything. I am not afraid of horses, nor of railroad wrecks—I have been in one or two and was not frightened—nor fires, nor—nor any of those things which come on a man unawares and where he has just to stand still, keep cool and do what he is told to do. But when it comes to other things, like going against another man’s will—oh, Paul—I am the biggest coward alive and I know it. I would never volunteer for the forlorn hope, but if there was an officer by the side of me with a pistol I’d march to the mouth of hell, because I would be more afraid of the officer than I would be of hell. That’s the sort of courage I have,” and Toni grinned shamelessly. “But before I tell you all of the evil things that have befallen me, tell me some more about Bienville. How does my mother look?”

“About twenty-five years older since you left. And Toni, you must write to her this very day—do you understand me?—to-day, and I shall write to her that she may get our letters together.”

“I will,” answered Toni. “And how about little Denise?”

As Toni said this, he blushed under his sunburned skin, and Paul laughed. They were both very young men and their thoughts naturally turned in the same direction.

“Denise is here with her father. Mademoiselle Duval has sold out the bakery shop, so I suppose you will no longer be in love with Denise.”

Toni giggled like a school-girl.

“To tell you the truth,” he said, “I never have thought about any girl except Denise, but I can only think of her now as a little creature in a checked apron with her flaxen plait hanging down her back.”

“She is an extremely pretty young lady, and a great belle with the young corporals. Mademoiselle Duval has given her a nice little dot of ten thousand francs to her fortune. But, for that reason, the sergeant, who is a level-headed old fellow, is looking around very carefully before he disposes of Denise’s hand.”

Toni struck his forehead with his open palm.

“Oh!” he cried, “Denise is not for me. I am only a private soldier—I never will be anything else.”

“You can be something else if you choose,” said Paul Verney.

“And I have been in the circus. The sergeant will never forgive me that.”

Paul shook his head dolefully. It was pretty bad, and the sergeant was a great stickler for correctness of behavior. But Paul, being a lover himself, and a poor man, who sincerely loved a rich girl, sympathized with Toni.

“Oh, well,” he said, “we must wait and see. One thing is certain—if Mademoiselle Denise takes a notion into her head to like you the sergeant will give in, for he is a very doting father. But, Toni, you must behave yourself after this.”

“Indeed I will,” replied Toni. “When I tell you what I have got by bad association, you will understand that I mean what I say.”

And then Toni, seating himself at Paul’s command, poured out the story of all that he had suffered at the hands of Nicolas and Pierre, ending up with that last dreadful account of the murder of Delorme.

“And that secret, Paul, I am carrying,” cried poor Toni, putting his fists to his eyes, into which the tears started, “and sometimes it’s near to killing me.”

Paul listened closely. He realized, quite as fully as Toni did, the position in which Toni had got himself, and did not make light of it.

“At all events,” he said, “I don’t think any one regretted Delorme’s death. He was the worst sort of a rascal—a gentleman rascal. You know he was the first husband of Madame Ravenel at Bienville.”

Toni nodded.

“I have seen many women in the seven years that I have been traveling about the world,” said Toni, “but I never saw one who seemed to radiate modesty and goodness as Madame Ravenel. Do the Ravenels still live at Bienville?”

“Yes.” The color came into Paul’s face, which was pink already. “They live there as quietly as ever, but much respected. They are no longer avoided, but still live very quietly.”

Toni, looking into Paul’s eyes, saw his face grow redder and redder, and his mouth come wide open, as Toni said, with a sidelong glance and his old-time grin:

“And Mademoiselle Lucie?”

“Beautiful as a dream,” replied Paul, with a lover’s fondness for superlatives, “and charming beyond words. Only,” here his countenance fell, “she has a great fortune from America, and why should she look at a sublieutenant in a dragoon regiment with two thousand francs a year and his pay?”

“If I recollect Mademoiselle Lucie aright,” answered Toni, “and she takes a notion into her head to like you, her grandmother will give in, because you used to tell me, in the old days when we sat in the little cranny on the bridge, that Mademoiselle Lucie said her grandmother allowed her to do exactly as she pleased.”

Paul laughed at having his own words turned against him.

“Oh, Toni!” he cried, “we are a couple of poor devils who love above our stations, both of us.”

“Not you,” replied Toni with perfect sincerity. “The greatest lady that ever lived might be proud and glad to marry you.” And as this was said by a person who had known Paul ever since he could walk, in an intimacy closer than that of a brother, it meant something. “I have seen Mademoiselle Lucie,” continued Toni. “I saw her one morning about two months ago, when you and she were riding together. She rides beautifully—I could not teach her anything in that line.”

“She does a great many things beautifully, and she is the most generous, warm-hearted creature in the world.”

“And just the sort of a young lady to fall in love with a poor sublieutenant and throw herself and her money into his arms.”

“But if the poor lieutenant had the feelings of a gentleman he could not accept such a sacrifice. He would run away to escape it.” Paul grew quite gloomy as he said this, and stroked his blond mustache thoughtfully. But it is not natural at twenty-two, with youth and health and a good conscience and abounding spirits, to despair. It was all very difficult, but Paul did not, on that account, cease loving Lucie.

“And does she still go to Bienville every year to visit Madame Ravenel?” asked Toni.

“Yes, every year, except two years that she spent in America. She is just home now, and very—very—American.”

Paul shook his head mournfully as he said this. He had all the prim French ideas, and the dash of American in Lucie frightened him, brave as he was.

Lucie.

“But, on her last visit to Bienville, before she went to America, her grandmother sent with her a carriage and a retinue of horses and servants, which quite dazzled Bienville. I think Mademoiselle Lucie bullies her grandmother shamefully. And whom do you think she pays most attention to of all the people in Bienville?”

Toni reflected a moment. “Monsieur and Madame Verney?”

Paul’s light blue eyes sparkled. “That’s just it. She has my mother with her all the time, and as for my father, he adores her, and Lucie actually pinches his arms and pulls his whiskers when she wants to be impertinent to him. You know she takes advantage of being half American to do the most unconventional things, and my father quite adores her—almost as much so as his son.”

“It looks to me,” remarked Toni, “as if Mademoiselle Lucie were taking things in her own hands, and meant to marry you whether you will or not. I have often heard that heiresses run great risks of being married for their money and then finding their husbands very unkind. Perhaps Mademoiselle Lucie knows this and wants to marry a man like yourself, who loves her for herself.”

“I think Mademoiselle Lucie has too much sense to marry me,” answered poor Paul quite honestly. “I think it is simply her kindness and generosity that make her kind to me and affectionate to my father and mother. She will marry some great man—a count or a duke perhaps—there are still a few left in France—and not throw herself away on a sublieutenant of dragoons,” and Paul sighed deeply.

The pair spent nearly two hours together. It seemed to Toni as if he could never be satiated with looking at his old friend, as pink and white and blond as ever. Paul felt the same toward Toni, and when, in the old way, Toni took Jacques out of his pocket and showed him, it was as if seven years passed away into mist and they were boys together. But at last Paul was obliged to dismiss Toni, who went back to his quarters with a heart lighter than it had been for seven years.

And he was to see more of Paul than he had dared to hope, for Paul had promised to arrange that Toni should be his soldier servant. The present incumbent was not exactly to Paul’s liking and he was only too glad to replace him with Toni.

There was work waiting for him, and that, too, under Sergeant Duval’s eye, and Toni did it with the energy of a man who is determined on pleasing the father of his beloved. No one would have recognized, in this smart, active, natty trooper, the dirty idle Toni of his boyhood. Sergeant Duval, however, was a skeptic by nature, and he waited to see more of Toni before reversing the notion he had formed of that young man. He had heard something, on his annual visits to Bienville, of Toni’s fondness for Denise, and, when she was in short frocks and pinafores, had sometimes joked her about it, but Denise, who blushed at the least little thing, would hide her head on her father’s shoulder and almost weep at the idea that she had even glanced at a boy.

Toni was longing to ask after Denise, but he dared not. As soon as he had a moment’s time to himself—and a recruit lately joined has not much leisure—he wrote a long letter to his mother. He did not write very well, and was a reckless speller, but that letter carried untold happiness and relief with it to the Widow Marcel at Bienville. His duties as Paul’s servant began at once. Toni was not overindustrious, but if he had to work for any one he would wish to work for Paul.

And then came a radiant time with Toni—a time when life seemed to him all fair. He managed to put that secret horror of Nicolas and Pierre out of his mind as they were out of his sight. He got his mother’s forgiveness by return of post, and he laid aside all the fear he had had of Nicolas and Pierre, and enjoyed the sight and the occasional society of the two beings who, with his mother, were nearest to him of the world—Paul Verney and Denise. He dared not mention Denise’s name to Sergeant Duval, who preserved the most unfeeling reticence about her toward Toni. The sergeant had no mind to encourage the attentions of young recruits, just out of the circus, to his pretty daughter with her splendid dot of ten thousand francs.

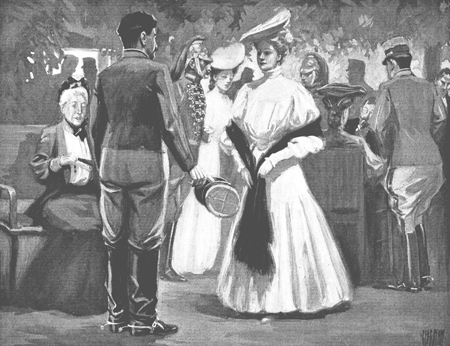

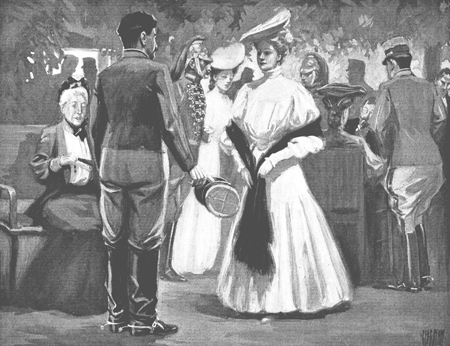

Toni, however, knew that the time of his service would come to an end in a year, and then he would be able to carry out that beautiful scheme that had haunted him during his circus life. He would become an instructor in a riding-school and earn big wages, as much as two hundred and fifty francs the month, and meanwhile he would lead so correct a life that even Sergeant Duval would be forced to approve of him. All these resolutions were very much increased by the first sight he caught of Denise. It was about a fortnight after he joined, and during that time he had kept his eyes open for the lady of his love. Although Sergeant Duval had quarters at the barracks, Denise and Mademoiselle Duval lived in lodgings in the town, and Toni did not have many opportunities of going into the town. One Sunday evening, however, a beautiful August Sunday, Toni found himself standing in the public square where the band played merrily and one of those open air balls, which are so French and so charming, was going on. Ranged on benches around were the older women, and among them Toni at once recognized the tall, angular, black figure of Mademoiselle Duval; and whirling around in the arms of a handsome dragoon with a beautiful pair of black mustaches, much finer than Toni’s, was Denise. Toni’s heart jumped into his mouth, his soul leaped into his eyes. It was Denise, of the acacia tree, and the buns, of long ago.

She was as blond, as modest, as neat as ever, but far prettier. Her fair hair was twisted up on her shapely head, on which sat a coquettish white hat. She wore a white muslin gown, with the short, full skirt much beruffled. Denise would have liked a train, but Mademoiselle Duval frowned sternly on such unbecoming frivolities as trained gowns for a sergeant’s daughter.

Denise had developed into as much of a coquette as Lucie Bernard had been, only in a different direction. Lucie achieved her conquests by a charming boldness, a bewitching unconventionality. Denise Duval succeeded in attracting the attention of the other sex by a demureness and quaint propriety which were immensely effective in their way.

Toni, having some instinctive knowledge of this, determined to proceed with great caution and military prudence. He would strive to carry the fortress of Denise’s affections by gradual approaches and not by assault. So, in pursuance of this plan, he walked up to Mademoiselle Duval and making a low bow said:

“Mademoiselle Duval, may I recall myself to your memory? I am Toni Marcel, the son of Madame Marcel, of Bienville, and had the honor of knowing you when I was a boy.”

Mademoiselle Duval gave him one grim look, and then cried out:

“Oh, I know you very well, Toni. You were the worst boy in Bienville, and as dirty as you were bad. Oh, how much trouble did you give your mother!”

This was not a very auspicious beginning for a young man who wished to become the nephew-in-law of the lady he addressed, but Toni was not deficient in the sort of courage which could take him through an emergency like that. He only said hypocritically, and with another bow and a sigh of penitence:

“Ah, Mademoiselle, every word that you say is true. I know I was very naughty and very idle, and my mother was far too patient with me. I gave her a great deal of trouble, but I hope to be a comfort to her in the future. I had a letter from her only yesterday in which, like the rest of your sex, Mademoiselle, she showed a beautiful spirit of forgiveness. I hope that she will come to visit me for a few days before long.”

Mademoiselle Duval was not greatly softened by this speech, but seeing Toni disposed to take a scolding meekly, she invited him to sit down by her side, when she harangued him on all his iniquities for the last seven years. The sergeant had told her that Toni had been in the circus and that was enough. Mademoiselle Duval warned Toni that all circus people were foredoomed to hell-fire, and that he would probably lead the procession. Toni took the attack on himself very meekly, but said:

“I assure you Mademoiselle, there were some good people in the circus—some good women, even.”

“Good women, did you say?” screamed Mademoiselle Duval, “wearing tights and spangles, and turning somersaults!”

Toni bethought him of the time when there was an outbreak of scarlet fever in the circus company and how these same painted ladies in tights and spangles stood by one another and nursed each other and each other’s children day and night, and uttered no word of complaint or reproach. He knew more than Mademoiselle Duval on the subject of the goodness and the wickedness which dwell in the hearts of men. He told Mademoiselle Duval, however, the story of the outbreak of scarlet fever. He had a natural eloquence which stood him in good stead, and Mademoiselle Duval, who was one of the best women in the world and had a soft heart, although a sharp tongue, was almost brought to tears by Toni’s story.

“There was a softness, almost a tenderness, in her look.”

Just then Denise’s cavalier brought her back to her aunt, and Toni, jumping up, profoundly saluted Denise. His soul rushed into his eyes, those handsome, daredevil black eyes which the prim and proper Denise had secretly admired from her babyhood. She glanced back at him as she courtesied to him with great propriety, and something in her face made Toni’s pulses bound with joy. There was a softness, almost a tenderness, in her look which Toni, having some knowledge of the world, interpreted to his own advantage. Denise’s own heart was palpitating, not tumultuously like Toni’s, but with a gentle quickness which was new to her.

“Ah, Mademoiselle,” said Toni, calling Denise Mademoiselle for the first time, “how well I remember you in my happy days at Bienville, when you used to give me buns under the acacia tree.”

He stopped. A soft blush came into Denise’s fair cheeks. She smiled and looked at him and then away from him. Denise remembered the bench under the acacia tree and all that had happened there well enough. Denise knew then, and knew now, that when the Toni of those days gave up something to eat to a small girl, his feelings were very deeply engaged to her. She recollected in particular the first afternoon the Ravenels took tea with the Verneys that Toni had selected one beautiful, ripe plum, and after eying it longingly, had put his arm around her neck and put the plum in her mouth, and what he had said then. Her blushing now revealed it all to Toni.

Suddenly the band struck up a waltz, Toni politely asked Denise to favor him with her hand for the dance, and they went off together. The moon smiled softly at them, and even the electric lights had a kind of tenderness in their glare, when Toni, clasping Denise in his arms for the first time, began to whirl around with her to the rhythm of the music. He felt himself raised above the earth—all his fears, all his evil-doing had departed from him—he felt, poor Toni, as if he would never be afraid of Nicolas and Pierre again, and as if that waltz was a foretaste of Heaven for him.

And Denise, too, was happy. He saw it in her shy eyes, in the softness of her smile, and presently Toni drew her closer to him and whispered:

“Denise, Denise, do you remember?” and Denise whispered back, “Yes, Toni, I remember all.”

And so as it was with Paul Verney and Lucie Bernard, they called each other by their first names when they were alone.

Presently in the mazes of the dance Toni looked up and there was Paul Verney passing through the square. He caught Toni’s eye and Toni grinned back at him rapturously. When the music stopped, Toni, putting Denise’s hand within his arm, escorted her back to the bench where Mademoiselle Duval sat knitting in the electric light. He contrived to pass directly in front of Paul Verney, whom he saluted respectfully, and Paul bowed low to Denise and said to her:

“Mademoiselle, we are both natives of Bienville, and I am most happy to see you here with your worthy aunt and your respected father,” and then Paul, with an eye single to Toni’s interests, walked on the other side of Denise up to where Mademoiselle Duval sat and promptly claimed acquaintance with her. In the old days at Bienville there had not been such a tremendous difference between Paul Verney, the poor advocate’s son, and the children of the pastry shop and the confectioner. Now Paul was an officer, but he was very pleasant and gentlemanlike, however, though quite dignified, and gave himself no haughty airs. He inquired with the deepest solicitude after Mademoiselle Duval’s health, remembered gratefully sundry tarts and cakes she had given him in the old days, and then said to her, in the most unblushing manner:

“And, Mademoiselle, we have here another citizen of Bienville, Marcel”—it was the first time that Paul had ever called Toni, Marcel, in his life—“who, I assure you, is worthy of our old town. He is strictly attentive to his duties, and the best rider in my troop. I predict that he will be a corporal before his enlistment is out.”

And thus having advanced Toni’s cause with his prospective aunt-in-law, Paul Verney withdrew, winking surreptitiously at Toni as he went off. It was impossible that Mademoiselle Duval should not revise her opinion of Toni after this testimony from his officer, so Toni at once found himself in a most acceptable position with Mademoiselle Duval. He danced twice more with Denise, carrying her off in the face of a couple of corporals, and, by his devoted attentions and insidious flattery of Mademoiselle Duval, gained that lady’s good-will. He would have liked to escort his old friends back to their lodging, but, as he explained, he barely had time to reach the barracks before the tap of the drum, and he scurried off, the happiest trooper in Beaupré that night.

When he neared the quadrangle on which the barracks faced, he overtook Paul Verney, and as he rushed past he whispered in his ear:

“Thank you, thank you, dear Paul.”

In that moment he could have not refrained, to save his life, from calling his lieutenant Paul.