XVIII

TROUBLE AT THE PRESCOTT ARMS

A few minutes later, as I swung along the highway toward the Prescott Arms, I saw Cecilia Hollister riding toward me at a lively gallop. She crossed the bridge without checking her horse, and then, with a hurried glance over her shoulder, she pointed with her crop to a by-way that led deviously into a strip of forest and vanished.

I hurried after her, and found her waiting for me in a quiet lane. She had dismounted and seemed greatly disturbed as I addressed her. Her horse, a superb Estabrook thoroughbred, had evidently been pushed hard. Cecilia had taken off her hat, and was giving a touch to the wayward strands of hair that had been shaken loose in her flight. The color glowed in her dark cheeks, and her eyes were bright with excitement.

"I hadn't expected to meet you; I thought you rode off with your aunt toward Mt. Kisco."

"We did; but on our way home Aunt Octavia stopped to call on a friend, and as I did n't feel in a mood for visits this morning I rode on alone."

She spoke further of her aunt's friend, of whom I had never heard before, to calm herself before touching upon the cause of her wild ride or her wish to speak to me. She pinned on her hat and drew on her riding-gloves while I helped to make conversation, and soon regained her composure. The haste with which she had withdrawn into the wood, and the imperative wave of her crop by which she had bidden me follow her, indicated that something of importance had happened and that she wished to confide in me.

"I was walking my horse in the road beyond Bedford, just after I left Aunt Octavia, when who should ride up beside me but Mr. Wiggins. He had evidently been following me."

She expected me to express surprise; and with the information that Hezekiah had just imparted fresh in my mind I dare say she was not disappointed in the effect of her words. I was thinking rapidly and fearfully. If my friend had sought her in the highway and offered himself in some fresh accession of ardor, he might even now be a rejected and hopeless man; but I was unwilling to believe that this had happened.

"Hartley is fond of riding, and nothing could be more natural than for him to have his horse sent out from town."

"Oh, it's natural enough," she cried; "but I was greatly taken aback when he rode up beside me."

"An old friend joining you in the highway, on a bright October morning! I can't for the life of me see anything surprising or alarming in that, Miss Hollister."

"But only yesterday, you remember I told you I had seen him walking with my sister."

"It's perfectly easy to talk to Hezekiah! It seems to me that that only shows a friendly attitude toward all the family. Let us deal with facts if I am to help you. I understand perfectly that Hartley Wiggins wishes to marry you; and that being the case I see no reason why he should n't be courteous to your sister. I 've always heard that it's the proper thing to be polite to the sisters, cousins, and aunts of one's prospective wife. I know of no more delightful occupation than listening to Hezekiah. Just now, for an hour or so, I have been enjoying her conversation myself. Nothing could be more refreshing or stimulating. She is an unusual young woman, and most amazingly wise."

"You have seen Hezekiah this morning!" she exclaimed.

"I have indeed. I hope I may say that she and I are becoming good friends. I am learning to understand her; though, believe me, I don't speak boastingly. However, this morning we got on famously together. But won't you continue and tell me what happened in the road when Hartley rode up beside you?"

"Oh, nothing happened; really nothing! Nothing could have happened, for the excellent reason that I ran away from him. It was n't what he did or said; it was the fear of what he might say!"

"If it had been Mr. Dick who had joined you in exactly the same way in the highway, you would not have minded in the least, Miss Hollister. Is n't that the truth?"

Her hand that had rested on the pommel of her saddle dropped to her side, and she stood erect, her eyes wide with wonder.

"What do you mean?" she gasped.

"I mean exactly what I have said; that if it had been that strutting young philosopher from the West you would—well, you would have allowed him to say what was in his mind, no matter whether it had been his latest thought on Kantianism, the weather, or his admiration for yourself. Am I not right?"

"I wonder, I wonder"—she faltered, drawing away, the better to observe me.

"You wonder how much I know! To relieve your mind without parleying further, I will say to you that I know everything."

"Then Aunt Octavia must have told you; and that seems incredible. It was distinctly understood"—

"Your aunt told me nothing. Not by words did any one tell me."

"Not by words?" she asked, eyeing me wonderingly and clearly fearing that I might be playing some trick upon her. "Then can it be that Hezekiah—but no! Hezekiah does n't know!"

"Trust Hezekiah for not telling secrets," I answered evasively. "Give me credit for some imagination. The air of Hopefield is stimulating, and in the few days I have spent in your aunt's house I have learned much that I never dreamed of before. I am not at all the person you greeted with so much courtesy in the library when I arrived there, a chimney-doctor and an ignorant person, a few afternoons ago,—called, as I thought, to prescribe for flues that proved to be in admirable condition, but really summoned by higher powers to assist the fates in the proper and orderly performance of their duties to several members of the house of Hollister,—yourself among them."

"I don't understand it; you are wholly inexplicable."

"I am the simplest and least guileful of beings, I assure you. Yet I have done some things here not in the slightest way related to chimney doctoring; and something else I expect to do for which I believe you will thank me through all the years of your life."

"Ah, if you really know, that is possible!" she sighed wearily. "I am very tired of it all. I was very foolish ever to have agreed to Aunt Octavia's plan. You have seen those men,—any one of them might, you know"— And she shrugged her shoulders impatiently.

"Any one of them might be the seventh man! There, you see I do know! And I mean to help you!"

She was immensely relieved; there was no question of that. Gratitude shone in her eyes; and then, as I marvelled at their beautiful dark depths, fear suddenly possessed them. The change in her was startling. Several motors had swept by in the outer road while we talked; they were faintly visible through the trees; and just now we both heard a horse and caught a fleeting glimpse of Hartley Wiggins, riding slowly with bowed head toward the inn. Cecilia's horse flung up his head, but she clapped her hands upon his nostrils and held them there to prevent his whinnying until that figure of despair had passed out of hearing.

I was smitten with sorrow for Hartley Wiggins. I could put myself in his place and imagine his feelings as he rode like a defeated general back to the inn, there to face the other suitors after the humiliating experience which Cecilia Hollister had just described. In his ignorance of the cause of her eagerness to escape from him, he no doubt believed that he had all unconsciously made himself intolerable to her. It was plain that that glimpse of him had touched Cecilia's pity; if I had doubted the sincerity of her regard for him before, I spurned the thought now. I was anxious to requicken hope in her,—an odd office for me to assume when in my own affairs I had always yielded my sword readily to the blue devils! Yet during my short stay at Hopefield I had already found it possible to restore Miss Octavia's confidence in her own chosen destiny, and in this delicate love-affair between Cecilia Hollister and my best friend I proffered counsel and sympathy with an assurance that astonished me.

"I have told you enough, Miss Hollister, to make it clear that I am in a position to help you. Believe me, I have no other business before me but to complete the service I have undertaken."

"But there is always"—she began, then ceased abruptly, and lifted her head proudly—"there is always Mr. Wiggins's attitude toward my sister. Not for anything in the world would I cause her the slightest unhappiness. You must see that, now that you know her."

I laughed aloud. Cecilia's concern for Hezekiah's happiness was so absurd that I could not restrain my mirth for a moment. Displeasure showed promptly in Cecilia's face.

"I am sorry if you doubt my sincerity, Mr. Ames. I will put the matter directly, to make sure I have not been misunderstood heretofore, and say that if Hezekiah is interested in Hartley Wiggins and cares for him in the least,—you know she is young and susceptible,—I shall take care that he never sees me again."

"Pardon me, but maybe you don't quite understand Hezekiah!"

"Is it possible, then, that you do?" she inquired coldly. "I imagine your opportunities for seeing her have not been numerous."

"Well, it is n't so much a matter of seeing her, when you've read of her all your life and dreamed about her. She's in every fairy story that ever was written; she dances through the mythologies of all races. Hers is the kingdom of the pure in heart. Her mind is like a beautiful bright meadow by the sea, and her thoughts the dipping of swallow-wings on lightly swaying grasses."

Cecilia's manner changed, and she smiled.

"You seem to have an attack of something; it looks serious. You have n't known her long enough to find out so much!"

"Longer than you would believe. She and I sat on the shore together when Ulysses sailed by; we were among those present at the sack of Troy; we heard Roland's ivory trumpet at Roncesvalles."

"Such words from you amaze me. I didn't imagine there was so much romance in chimneys."

"They are full of it! Commend me to an open fire, with a flue that knows its business, and a dream or two! I 've renounced my profession. I shall hereafter offer myself as adviser to persons in need of illusions; we 'd all be poets if we dared!"

I helped her into the saddle, and she looked down at me with amusement in her eyes. My praise of Hezekiah had pleased her, and I felt, as when we journeyed together into town, her kindly, human qualities. The perplexities and embarrassments resulting from her compact with her aunt had doubtless checked the natural flow of her spirits. She talked on buoyantly, though I was eager to be off, to avert the catastrophe that only her flight had prevented and which Wiggins might at any moment precipitate. She gathered up her reins.

"You are not coming home for luncheon? Then I shall see you at four. I hope the hiding-place of the ghost will prove interesting. Aunt Octavia has built her hopes high, and I may add that she has expressed the greatest admiration of you to me. On her ride this morning she declared that great things are in store for you. I hope so, too, Mr. Ames."

She gave me her hand and rode away, and before I had reached the highway she was across the bridge and galloping rapidly homeward.

The inn was a mile distant, and I set off at a brisk pace, turning over in my mind various projects for controlling the characters now upon the stage in such manner that Wiggins should become the seventh man. Cecilia could not always run away from him without violating the terms of her aunt's stipulation; and it was unlikely that she would attempt further to guide or thwart the pointing finger of fate. I relied little upon any arrangement effected among the suitors to stand together. Hume had already found a chance to speak. Lord Arrowood had bitten the dust and turned his face homeward, and Wiggins had been near the brink only that morning. It was unlikely that any of the active candidates remaining would stumble upon the key to the situation, which Hezekiah had given into my keeping.

It was well on toward two o'clock when I approached the inn. Before long the suitors would depart for their afternoon call at the Manor, which was an established event of the day. Just as I was about to enter the gate I was arrested by an imperious voice calling, and John Stewart Dick came running toward me. He had evidently been expecting me, and I paused, thinking him about to renew his attack upon me. To my surprise he greeted me cordially, even offering his hand.

"You thought you would come after all. Well, I'm glad you did. I've decided that there should be peace between us."

In stature he was the shortest of the suitors, but what he lacked in height was compensated for by a tremendous dignity. A dark Napoleonic lock lay across his forehead, and his clear-cut profile otherwise suggested the Corsican, the resemblance being, I wickedly assumed, one that the philosopher encouraged.

"You have several times addressed me, Mr. Ames, in a spirit of contumely which I have hesitated to punish by the chastisement you deserve; but I am willing to let bygones be bygones."

His changed tone put me on guard, but it was impossible for me to take him seriously. In spite of the fact that he was a vigorous muscular young fellow who could have threshed me without trouble, I could not resist the impulse he always roused in me to address him in language any self-respecting man would resent.

"Chant the dies iræ with considerable allegro, Plato, for I am hungry and would fain pay for food at the adjacent inn."

"I will overlook the coarseness of your humor," he rejoined haughtily. "My own time is as valuable as yours. You have sneered at my attainments as a philosopher; but I will pass that for the present. I am disposed to treat you magnanimously. You have an excellent opinion of yourself; you have come here as an intruder upon the rights of those of us who followed Cecilia Hollister across Europe and home to America; but in spite of this I waive my rights in your favor. I had intended to offer myself to Miss Hollister this afternoon, with every hope of success, but I yield to you. My only request is that you inform me at once when you have learned her decision."

He clapped on his cap and folded his arms, clearly satisfied with the expressions of surprise to which my feelings betrayed me. Could it be possible that he had guessed the truth, perhaps by deductive processes of which I was ignorant? Whether he had reasoned from some remark thrown out by Miss Octavia as to the influence of seven in the affairs of life and her application of that fateful principle to the choice of a husband for Cecilia, I could not guess, but assuming that he had caught that clue, he might readily enough have managed the rest. Having crossed on the steamer with the suitor host, a man of his intelligence might readily enough have kept track of the vanquished. In any case he had hit upon me as a likely victim, and on the plea of generously waiting till I had tried my luck he hoped to thrust me forward as the sixth suitor, and immediately thereafter project himself as the inevitable seventh man. The whole situation was rendered perilously complex by the knowledge that, unaided, he had possessed himself of so much dangerous information. I must not, however, allow him to see what I suspected.

"My dear professor, there's an ancient warning against the Greeks bearing gifts. You must give me time to inspect the horse."

"Are you questioning my good faith?"

"Be it far from me! I'm a good deal tickled though by your genial assumption that if I offered myself to this lady I should be declined with thanks. You have fretted yourself into a state of mind that bodes ill for American philosophy."

He was again belligerent. It may have occurred to him that I might know as much as he, but at any rate he grinned; it was a saturnine grin I did not like.

"I'm starving to death at the door of an inn, and you must excuse me. Have you seen Hartley Wiggins lately?"

"I have, indeed! He's taken to lonely horseback rides; he's off somewhere now. He has n't the stamina for a contest like this. One by one the autumn leaves are falling," he added, with special intention, "and I have given you your chance."

"Thanks, light-bringing Socrates from the lands of the Ogalallas! For so much courtesy I shall take pleasure in reading all your posthumous works. Let us cease being absurd."

He laid his hand on my arm and lowered his tone.

"Don't be an ass. If you and I both know what's underneath all this mystery we might come to an understanding."

"I don't follow you. Please make a light, like a man about to have an idea."

"You mean that you don't understand?" He eyed me doubtfully, uncertain whether I knew or not.

"You have implied that I am incapable of understanding; suppose we let it go at that."

With this I left him and entered the low-raftered office—it was really a pleasant lounging-room, unspoiled by the usual hotel-office paraphernalia. Dick had followed close behind, and as I paused, hearing voices raised angrily in the dining-room beyond, I turned to him for an explanation. As the suitors had been the only guests of the inn since their advent, having stipulated that the proprietor should exclude other applicants for meals or lodging, I attributed the commotion to strife in their own ranks. Dick nodded sullenly and bade me keep on.

"You 'd better take a look at those fellows. I 've quit them—quite out of it; remember that."

The dining-room door was slightly ajar, and I flung it open.

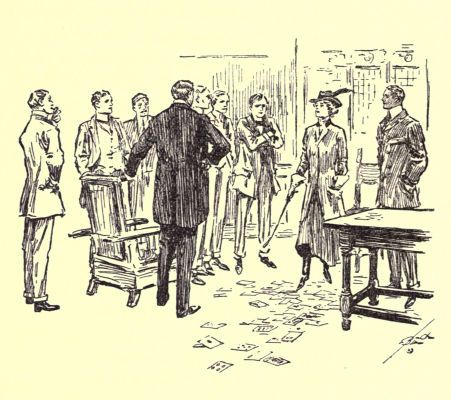

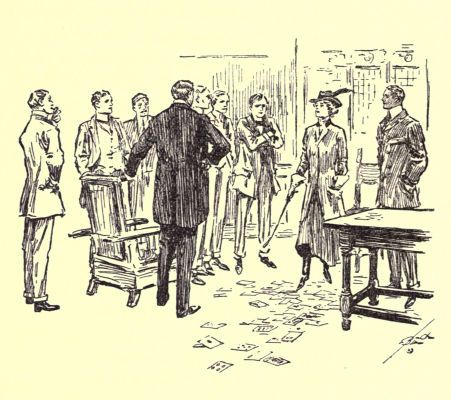

Ormsby, Shallenberger, Henderson, Hume, Gorse, and Arbuthnot had been engaged with cards at a round table in an alcove, but some dispute having apparently risen, they stood in their places engaged in acrimonious debate. As near as I could determine, some one of them—I think it was Ormsby—wished to abandon the game, which had been undertaken to determine in what order they should be permitted to pay visits to Hopefield in future, the calls en masse having grown intolerable. They were so absorbed in their argument that they failed to note my appearance, and I stood unobserved within the door. The dialogue between the card-players was swift and hot.

"It's no good, I tell you!" cried Ormsby. "There's no fairness in this unless all take their chances together!"

"You ought to have thought of that before we began. This was your scheme, but because the cards are running against you, you want to quit. I say we'll go on!" This from Henderson, who struck the table sharply as he concluded.

"You knew Wiggins and Dick were n't going in when we started, and you are not likely to get them in now. Your anxiety to cut the rest of us out by any means seems to have unsettled your mind," shouted Gorse. "I say let's drop this and stand to our original agreement that no man speak till the end of the fortnight."

"After that whole scheme has been torn to pieces like paper! There's been nothing fair in this business from the start! We ought to have kept Arrowood here and held together. And we ought to have got rid of that Ames fellow—he did n't belong in this at all; and instead of protecting ourselves against outsiders we have sat here like a lot of fools while he's been making himself agreeable there in the house—right there in the house!"

Ormsby's voice rose to a disagreeable squeak as he closed with this indictment of me. Hume fidgeted uneasily, and met my eye so warily that I wondered whether he suspected that I knew of his breach of faith with the other suitors. Much dallying with Scandinavian literature had not lightened his heart, and there was nothing in Ibsen to which he could refer his present plight. Shallenberger seemed to be the only one of the group who had not lost his senses. He was in the farther corner of the alcove, out of sight from the door, but I heard him distinctly as he addressed the other suitors with rising anger.

"We're acting like cads, and cads of the most contemptible sort! I only agreed to this game to satisfy Ormsby. The idea of our sitting here to draw cards to determine the order in which we shall offer ourselves to the noblest and most beautiful woman in the world would be coarse and vulgar if it were not so ridiculous! The men who had their chance on the steamer or after we came here—and I don't pretend to know who they are—ought in decency to have left the field. We seem to have forgotten that we pretend to be gentlemen; or, far less pardonable, that we pay court to a lady. Damn you all! I refuse to have anything more to do with you, and if you try to interfere with my affairs in any way I'll smash your heads collectively or separately as you prefer!"

My interest in this colloquy had led me further into the room, and hearing my step they all turned and faced me. Dick had continued at my side, but the black looks they sent our way were intended, I thought, rather for me. Shallenberger, having taken himself out of the tangle, leaned against the wall and filled his pipe with unconcern. My appearance roused Ormsby to a fresh outburst.

"You're responsible! If you had n't forced yourself upon the ladies at Hopefield there would n't have been any of this trouble!"

"You're only an impostor anyhow. You went to the house to fix a chimney, and seem to think you 're engaged to spend the rest of your natural life there!" protested Henderson, twisting the ends of his moustache.

Then they dropped me and assailed Dick.

"We'd like to know what you expect to gain by dropping out! You got cold feet mighty sudden!" bellowed Ormsby.

Gorse and Henderson paid similar tributes to the apostate, whose melancholy grin only deepened. Shallenberger was pacing the floor slowly and puffing his pipe. Hume and Arbuthnot growled occasionally, but shared, I thought, Shallenberger's changed feeling.

My silence had been effective up to this time, but I was afraid to risk it longer. Dick, I imagined, had kept close to me for fear of missing any part of the altercation he knew my appearance would provoke. The more vociferous suitors had howled themselves hoarse and glared at me while I considered the situation. Henderson rallied for a final shot.

"A good horsewhipping is what you deserve," he cried, leveling his finger at me.

"Gentlemen," I began, not without inward quaking, "you have spoken loud naughty words to me, and in reply I must say that your vocal efforts suggest only the melodies of the braying jackass, and that your manners, to speak mildly, are susceptible of considerable improvement."

"You leave this neighborhood within an hour!" boomed Ormsby; and in his efforts to free himself from his chair it fell backward with a crash that echoed through the long room.

"Then summon the coroner by telephone, for I shall not be taken alive," I answered quietly, trying to recall my youthful delight in Porthos, Athos, and Aramis. "I should dislike to change the mild color-scheme of this pleasant dining-room, but as sure as you lay hands on me, these walls will become a playground for any corpuscles you carry in your loathsome persons."

"Come along, let us put him out," Henderson was saying in an aside to Ormsby.

"You were playing a game here for a stake not yours for the winning," I continued. "Now I suggest that you shuffle the pack,—you three, who are so full of valor,—shuffle the pack, I say, and draw for the jack of clubs. Whoever is the fortunate man I shall take pleasure in pitching through yonder very charming casement."

"Agreed!" cried Henderson, and the three flung themselves into their chairs.

The alacrity of their consent had unnerved me for a moment. D'Artagnan, I was sure, would have fought them all, but I consoled myself, as the cards rattled on the bare table, with the reflection that, considering the fact that I had never in my life laid violent hands on a fellow-being, I was conducting myself with admirable assurance. My weight has always hung well within one hundred and thirty, and physicians have told me that I was incapable of taking on flesh or muscle. Any one of these men could easily toss me through the window I had indicated as a means of their own exit.

Shallenberger caught my eye and indicated with a slight jerk of the head that I had better run before it was too late. The painstaking care with which Henderson had fallen upon the cards was disquieting, to put it mildly. Dick nudged me in the ribs and offered to hold my coat.

"It will not be necessary," I replied carelessly. "Tender your services to the other gentlemen."

I felt the cold sweat gathering on my brow. The three had begun to draw cards, and I heard them slap the bits of pasteboard smartly upon the table as they lifted them from the deck and, finding the jack of clubs still undrawn, waited the next turn. I had no idea that a pack of cards would dissolve so readily by the drawing process, and my memory ceased trying to recall the adventures of D'Artagnan and hovered with ominous persistence about the mad don of La Mancha. I cannot say now whether I stood my ground out of sheer physical inability to run or from an accession of courage due to the remembrance of my success in detecting the Hopefield ghost. In any case I affected coolness as I waited, even throwing out my arms to "shoot" my cuffs once or twice, and yawning.

"Come, gentlemen, hurry: let us not waste time here," I exclaimed impatiently.

"If Ormsby turns up the card you're a dead man," Dick was muttering gloomily.

"They're all alike to me," I replied loudly. "Mr. Ormsby is very beautiful; I shall hope not to disfigure him permanently;" but as I spoke my tongue was a wobbly dry clapper in my mouth.

I was bending over now, watching the three men pick up the cards, and once, when I misread the jack of spades for the jack of clubs, a shudder passed over me. They were down to the last card, and Ormsby's hand was on it. I recall that a group of steins on a shelf over Henderson's head seemed to be dancing wildly. Then I looked at the floor to steady myself, and hope leaped within me, for there, by Ormsby's foot,—a large and heavy one,—lay an upturned card, the jack of clubs, whose lone symbol magnified itself enormously in my amazed eyes.

At this moment, I became conscious that something had occurred to distract the attention of the other men, who were staring at some one who had entered noiselessly.

"Gentlemen, you seem immensely interested in the turn of those cards. I am glad to have arrived at the critical moment. Mr. Ormsby, will you kindly lift the remaining card from the table?"

Miss Octavia stood beside me. She was dressed in a dark brown riding-habit; the feather in her fedora hat emphasized her usual brisk air. She swung her riding-crop lightly in her hand, and bent over the table with the deepest interest.

Ormsby turned up the card. It was the ten of diamonds.

"Gentlemen," I cried, pointing to the card, "what trick is this? Can it be possible that you have been trifling with me in a fashion for which men have died the world over by sword and pistol!"

"Kindly explain, Arnold, the nature of this difficulty," Miss Octavia commanded.

"Simply this, Miss Hollister, if I must answer; I had offered to fight these three gentlemen in order. It was agreed that the man who drew the jack of clubs from the pack with which they had been playing should be my first victim. They have shuffled their own cards and have drawn the whole pack and there is no jack of clubs in the pack! The only possible explanation is one to which I hesitate to apply the obvious plain Saxon terms."

"It dropped out, that's all! You don't dare pretend that we threw out the jack to avoid drawing it!" protested Ormsby, though I saw from the glances the trio exchanged that they suspected one another. Ormsby and Gorse bent down to look for the missing card, but before they found it I stepped forward and drove my fist upon the table with all the power I could put into the blow.

"Stop!" I cried. "I gave you every opportunity to stand up and take a trouncing, but I need hardly say that after this contemptible knavery I refuse to soil my hands on you!"

"Do you insinuate"—began Henderson, jumping to his feet.

"Gentlemen," said Miss Hollister, lifting the riding-crop, "it is perfectly clear to me that Mr. Ames has gone as far as any gentleman need go in protecting his honor. I do not offer myself as an arbitrator here, but I advise my young friend that nothing further is required of him in this deplorable affair."

With one sweep of her crop she brushed to the floor the three piles of cards that lay on the table as they had been stacked when drawn.

With one sweep of her crop she brushed to the floor the three piles of cards.

"Arnold," she said, with indescribable dignity, "will you kindly attend me to my horse?"