XIX

THE GHOST OF ADONIRAM CALDWELL

A stable-boy held Miss Octavia's horse at the inn-door. Her face, her figure, her voice expressed outraged dignity as she tested the saddle-girth.

"You need never tell me what had happened to provoke your wrath, for that is none of my affair; but I wish to say that your conduct and bearing won my highest approval. They had undoubtedly hidden the jack of clubs to avoid the drubbing you would have administered to the unfortunate man who would have drawn that card if it had been in the pack."

"I was not in the slightest danger at any time, Miss Hollister," I protested. "By one of those tricks of fate to which you and I are becoming so accustomed, the card had fallen to the floor unnoticed. If you had not arrived so opportunely the lost jack would have been discovered, the cards reshuffled, and very likely Mr. Ormsby would have been dusting the inn-floor with me at this very minute."

"I refuse to believe any such thing," declared Miss Octavia, who had mounted and continued speaking from the saddle. "Your perfect confidence was admirable, and I shudder to think of the terrible punishment you would have given them. I do not particularly dislike Mr. Ormsby, though the possibility of Cecilia marrying him has troubled me not a little as I have recalled the unromantic aspect of Utica as seen from the car-windows; but it is much to your credit that you defied them all and brought them to the fighting-point, and then, by a stroke of cleverness it pleased me to witness, placed them irretrievably in the wrong."

If Miss Octavia wished to view my performances in this flattering light it seemed unnecessary and unkind to object. Now that I was in the open again with a whole skin I was not averse to the victor's crown; I would even wear it tilted slightly over one ear. Birds have been killed by shots that missed the real target; bunker sands are rich in gutta percha and good intentions. I was a fraud, but a cheerful one.

"It was only a pleasant incident of the day's work, Miss Hollister. I'm going to engage a squire and take to the open road as soon as all this is over."

"As soon as all what is over!" she demanded, eyeing me keenly.

"Oh, the work I've undertaken to do here. I flatter myself that I have made some progress; but within twenty-four hours I dare say that we shall have seen the end."

"Your words are not wholly luminous, Arnold."

"It is much better that it should be so. You have trusted me so far, and I have no intention of failing you now. If I say that the crisis is near at hand in a certain matter that interests you greatly, you will understand that I am not striking ignorantly in the dark."

"If you know what I suspect you know, Arnold Ames, you are even shrewder than I thought you, and you had already taken a high place in my regard. The curtains of the windows just behind you have shown considerable agitation since we have been speaking, not due, I think, to the wind, as there is no air stirring. Those gentlemen you have just vanquished are timidly watching you. Your daring and prowess have greatly alarmed them. You may be sure they will think twice before provoking your wrath again."

"I devoutly hope they will," I replied, glancing carelessly over my shoulder, and catching a glimpse of Henderson as he drew hastily out of sight. "But will you tell me just how you came to visit the inn at this particular hour?"

"Nothing could be simpler. I had luncheon at the house of a friend on whom I called. Cecilia had left me to continue her ride alone, and on my way home I thought I would ride by the Prescott Arms to see how the guests were faring. You see,"—she paused and gave a twitch to her hat to prolong my suspense,—"you see, I own the Prescott Arms!"

With this she rode away, and not caring to risk a further meeting with the angry suitors from whom Miss Octavia had rescued me by so narrow a margin, I set off across the fields toward Hopefield. From the stile I saw Miss Octavia in the highway half a mile distant, sending her horse along at a spirited canter. I reached the house without further adventures, was served with a cold luncheon in my room, and by the time I had changed my clothes Miss Octavia sent me word that Pepperton had arrived.

Miss Octavia and the architect were conversing earnestly when I reached the library; and from the abruptness with which they ceased on my entrance I imagined that I had been the subject of their talk. Pepperton is not only one of the finest architects America has produced, but one of the jolliest of fellows. He grasped my hand cordially and pointed to the fireplace.

"So you've at last found one of my jobs to overhaul, have you! You must n't let this get out on me, old man; it would shatter my reputation!"

"Please observe that the flue is drawing splendidly now," I answered. "A ghost had been strolling up and down the chimney, but now that I have found his lair he will not trouble Miss Hollister's fireplaces again."

"I have waited for your arrival, Mr. Pepperton, that we might have the benefit of your knowledge of the house in following the trail of this ghost which Arnold has discovered. But we must give Arnold credit for effecting the discovery alone and unaided. I destroyed the plans I obtained from your office so that Arnold might be fully tested as to his capacity for managing the most difficult situations."

When Miss Octavia first referred to me as Arnold, Pepperton raised his brows a trifle; the second time he glanced at me laughingly. He seemed greatly amused by Miss Octavia's seriousness, but her amiable attitude toward me clearly puzzled him.

"It takes a good man to uncover a thing I try to hide. I said nothing to you, Miss Hollister, about the retention within the walls of this house of parts of an old one that formerly occupied the site, for the reason that I thought you might refuse to buy the estate. The gentleman for whom I built Hopefield was superstitious, as many men of advanced years are, as to the building of a new house, and as the site he chose is one of the finest in the county he compelled me to construct this house—which is the most satisfactory I have built—in such manner enough of the old should be kept intact to soothe his superstitious soul with the idea that he had merely altered an old house, not built a new one. As it is the architect's business to yield to such caprices I obeyed him strictly. So there are two rooms of an old farmhouse hidden under the east wing, and it amused me, once I had got into it, to preserve part of the old stairway, and connect the retained chambers with the upper hall of this house. I had to patch the original stair, which was only one flight, with discarded lumber from the old house, but I flatter myself that I managed it neatly. I even saved the old nails to avert the wrath of the evil spirits. When the umbrella and dyspepsia-cure man died,—for he did die, as you know,—I believed the secret had died with him, as he was very sensitive about his superstitions. Most of the laborers on that part of the job were brought from a long distance, and I supposed they never really knew just what we were doing. I might have known, though, that if a fellow as clever as Ames got to pecking at the house the trick would be discovered. But the chimney, old man,—what on earth was the matter with it?"

"It will never happen again, and I promised the ghost never to tell how it was done."

"You were quite right in doing that, Arnold,—a ghost's secrets should be sacred; but let us now proceed to the hidden chambers," said Miss Hollister, rising without further ado.

She summoned Cecilia, to whom we explained matters briefly, and at Pepperton's suggestion the four of us went directly to the fourth floor, so that Miss Octavia might see the whole contrivance in the most effective manner possible.

My awkward pen falters in the attempt to convey any idea of Miss Octavia's delight in Pepperton's revelation; she kept repeating her admiration of his genius, and her praise of my cleverness, which, to protect Hezekiah, I was forced to accept meekly. When in broad daylight Pepperton found and pressed the spring in the upper hall and the hidden door opened, with a slowness that indicated a realization of its own dramatic value, Miss Octavia cried out gleefully, like a child that witnesses the manipulation of a new and wonderful toy.

"To think, Cecilia, that I should never have known of this if that chimney had not smoked!"—a remark that caused Pepperton to glance at me curiously. He knew as well as I did that with ordinary care every flue in that house would have drawn splendidly. "Beyond any question," Miss Octavia kept asserting, "beneath the chambers of the old house down there we shall find the bones of that British soldier who perished here; or it is even possible that a chest of hidden treasure is concealed beneath the floor. What do you yourself suspect, Mr. Pepperton?"

We were lighting candles preparatory to stepping down into the dark stairway, and Pepperton was plainly hard put to keep from laughing.

"I assure you, Miss Hollister, that I have told you all I know about the rooms down there. I 'm not very strong in the ghost-faith; and our friend the umbrella-man never dreamed of such a thing, I assure you, not even after he had satisfied his fierce craving for pie."

Miss Octavia followed Pepperton slowly, pausing frequently to hold her candle close to the stair-walls, whose rough surfaces confirmed all that Pepperton had said of the preservation of the old timbers. I had brought a handful of candles, and when we had reached the dark rooms beneath, I lighted these and set them up in the black corners of the old rooms, in which, Miss Octavia remarked, not even the wall paper had been disturbed. The exit into the coal-cellar, and concealed openings left for ventilation which had escaped me before, were now pointed out by the architect, who kept laughing at the huge joke of it all.

Cecilia murmured her surprise repeatedly as we continued the examination; nothing quite like this had ever happened in the world before, but even as we walked through those hidden rooms my thoughts reverted to the crisis so near at hand in her affairs. I had pledged myself to her service, but I saw no way yet of assuring the proper sequence of proposals. The ultimate seventh must be Wiggins; but how could I manage the penultimate sixth! Cecilia's own apparent freedom from care on this tour of inspection deepened my sense of responsibility to all concerned. Dick might by now have persuaded some one of the others at the inn to offer himself, thus closing the gap, and I had determined that the Westerner should not outwit me. It was some consolation to know that while Cecilia was in these lost rooms in my company, she was safe from Dick's machinations.

My thoughts were, however, given a new direction by Miss Octavia. She had been scrutinizing the floor closely, asking us all to bring our candles to bear upon it, that she might search thoroughly for any signs of a trapdoor beneath which the bones of the British soldier might repose.

"You can't tell me," she averred in her own peculiar vein, "that a house as old as this has been preserved merely to divert calamity from a superstitious gentleman engaged in the manufacture of ribless umbrellas and a dyspepsia cure."

Miss Octavia Hollister was a woman to be humored; we all knew this; but I realized with a pang that she was about to be disappointed. I had expected her to forget the British soldier in the perfectly tangible joy of secret springs and ghostly chambers; and if I had foreseen her persistence in clinging to the tradition of the ill-fated Briton I should have taken the trouble to hide a few bones under the flooring. Miss Octavia had brought a stick from the coal-room, and was thumping the floor with it even while Pepperton tried to discourage her further investigations. We were all ranged about her with our candles, and these, with the others I had thrust into the corners, lighted the room well.

"I'm afraid you've seen the whole of it, Miss Hollister," said Pepperton. "The old house was built after the Revolution, I judge, but your British soldier was probably left hanging to a tree and never buried at all."

"Mr. Pepperton," she replied, holding the candle so close to the architect that he blinked, "it would be far from me to question your knowledge of history, but I should not be at all surprised if the builder of this old house had fought on the seas with John Paul Jones, and had buried beneath these walls the very sea-chest that had been his companion on many eventful voyages."

Pepperton gasped at the absurdity of this, and then suppressed his mirth with difficulty. Cecilia faintly expostulated; but I knew Miss Octavia would not be dissuaded, and I thought it as well to facilitate her search and be done with it. A sailor with rings in his ears and a cutlass dangling at his side might have come home from the wars and established himself on a farm in Westchester County and even buried his sea-chest under the floor of his house, but in all likelihood he never had. It was not my office, however, to advise Miss Octavia Hollister in such matters. Pepperton had changed his tune and seemed anxious to follow my lead. To him she was an eccentric old woman, whose wealth alone gained her indulgence in such preposterous obsessions as this; but my own feelings were those of regret that she must so quickly be disillusioned. To me she had become an incarnation of the play-spirit that never grows old, and there may have risen in me an honest belief that what this unusual woman sought she would somehow find. Once or twice when the uneven worn flooring had boomed hollowly under her stick I had knelt promptly to examine the planks, and had thus disposed of several false alarms. Pepperton feigned interest for a time, but was becoming bored. Cecilia studied the quaint pattern of the wall paper, which she said ought to be reproduced, as nothing in contemporaneous designs equaled it.

Miss Octavia had been over the floors of the two rooms twice, and was about to desist. Her less frequent appeals to the rest of us for confirmation of some suspected change in the responses to her thumping indicated disappointment. She made her last stand in the corner of the smaller room, and as we all stood holding our lights, we were conscious that the dull monotonous thump suddenly changed its tone. We all noticed it at the same instant, and exchanged glances of surprise.

"Do you hear that, gentlemen?"

She subdued her gratification in the rebuking glance she gave us. Calm and unhurried, she rested a moment on her stick, with the candle's soft glow about her, a smile ineffably sweet on her face.

"The timbers may have rotted away underneath. We did n't raise these floors," said Pepperton; but we both dropped to our knees and brought all the candle-light to bear upon the flooring. Dust and mortar, shaken loose in the destruction of the house, filled the cracks. Pepperton, deeply absorbed, continued to sound the corner with his knuckles.

"It really looks as though these boards had been cut for some purpose," he said, whipping out his knife.

I ran to the kindling-room and found a hatchet, and when I returned he had dug the dirt out of the edges of the floor-planks. Silence held us all as I set to prying up the boards.

"I beg of you to exercise the greatest care, gentlemen. If bones are interred here we must do them no sacrilege," warned Miss Octavia.

By this time we all, I think, began to believe that the flooring might really have been cut in this corner of the old room to permit the hiding of something. The room had grown hot, and Cecilia opened the cellar-windows outside to admit air. The old planks clung stubbornly their joists, but after I had loosened one, the others came up quickly and the smell of dry earth filled the room. Pepperton had, at Miss Octavia's direction, brought a chisel and crowbar from the tool-room in the cellar, and he stood ready with these when I tore up the last board, disclosing an oblong space about five feet long and slightly over three feet wide. It was possible that this was the whole story, but Pepperton began driving the bar vigorously into the close-packed soil. As he loosened the earth I scooped it out, and we soon had penetrated about six inches beneath the surface.

We were all excited now. The edge of the bar struck repeatedly against something that resisted sharply. It might have been a root, but when Pepperton shifted the point of attack the same booming sound answered to the prodding. Pepperton now thought it might be only an empty cask or a box of no interest whatever; but Miss Octavia, hovering close with a candle, encouraged us to go on, and was fertile in suggestions as to the most expeditious manner of resurrecting whatever might be buried there. We were pretty well satisfied from the soundings that the hidden object was somewhat shorter and narrower than the hole itself.

"Quite naturally so," observed Miss Octavia, "for a man who buries a treasure has to allow himself room for getting at it."

We worked on silently, Pepperton loosening the soil with the bar while I shoveled it out. In half an hour we had revealed a long flat wooden surface, which to our anxious imaginations was the lid of some sort of box.

"It's sound red cedar," pronounced Pepperton, examining the wood where the tools had splintered it.

"Of course it's cedar," replied Miss Octavia, bending down to it. "I knew it would be cedar. It always is!"

We paused to laugh at her confident tone, and Cecilia suggested that as there was still a good deal to do before we could free the box, we should send for some of the servants to complete the work.

"I would n't take a thousand dollars for my chance at this," Pepperton answered; and we fell to again.

It must have been nearly six o'clock when we dragged out into that candle-lighted chamber a stout, well-fashioned box. The earth clung to its sides jealously, and it was bound with strips of brass that shone brightly where the scraping of our tools had burnished it. We pried off the heavy lock with a good deal of difficulty, and when it was free Miss Octavia asserted her right to the treasure-trove with much calmness.

"I should never forgive myself if I allowed this opportunity to pass; you must permit me to have the first look."

"Certainly, Miss Hollister; if it had n't been for you this chest would have remained hidden to the end of all time," Pepperton replied.

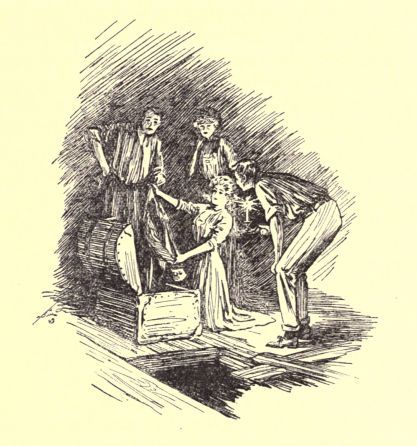

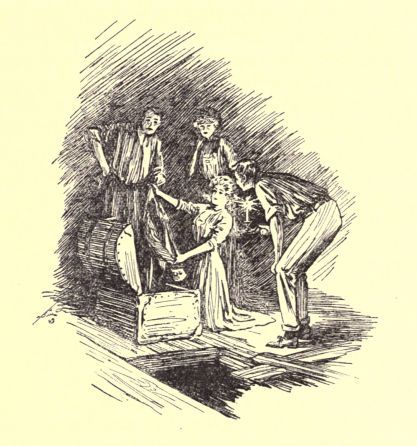

We gathered close about her as she knelt beside the box. My hand shook as I held my candle, and I think Miss Octavia was the only one in the room who showed no nervousness. Cecilia sighed deeply several times, and Pepperton mopped his face with his handkerchief. The lid did not yield as readily as we had expected, and it was necessary to resort to the hatchet and chisel again; but we were careful that it should be Miss Octavia's hand that finally raised the lid.

We all exclaimed in various keys as the light fell upon the open chest. The musty odor of old garments greeted us at once. The box was well filled, and its contents were neatly arranged. Miss Octavia first lifted out the remnants of a military uniform that lay on top.

Miss Octavia first lifted out the remnants

of a military uniform that lay on top.

"It's his ragged regimentals!" cried Cecilia, as we unfolded an officer's coat of blue and buff, sadly decrepit and faded; "and he was not a British soldier at all, but an American patriot."

Time and service had dealt even more harshly with an American flag on which the thirteen white stars floated dimly on the dull blue field. It had been bound tightly about a packet of papers which Miss Octavia asked Pepperton to examine.

"These are commissions appointing a certain Adoniram Caldwell to various positions in the Continental Army. Adoniram had the right stuff in him; here he's discharged as a private to become an ensign; rose from ensign to colonel, and seems to have been in most of the big doings. 'For gallantry in the recent engagement at Stony Point, on recommendation of General Anthony Wayne'—by Jove, that does rather carry you back!"

Half a dozen of these documents traced Adoniram Caldwell's career to the end of the Revolution and his retirement from the military service with the rank of colonel. A sealed letter attached to these commissions next held our attention. The ends were dovetailed in the old style before the day of envelopes, and evidently care had been taken in folding and sealing it. The superscription, in a round bold hand, without flourishes, read: "To Whom It May Concern."

"I suppose it concerns us as much as anybody," remarked Miss Octavia. "What do you say, gentlemen; shall we open it?"

We all demanded breathlessly that she break the seal, and we were soon bending over her with our lights. The ink had blurred and in spots rust had obliterated the writing:—

"I, Roger Hartley Wiggins, sometime known as Adoniram Caldwell"—

"Hartley Wiggins!" we gasped; and I felt Cecilia's hand clasp my arm.

Miss Octavia continued reading, and as she was obliged to pause often and refer illegible lines to the rest of us, I have copied the following from the letter itself, with only slight changes of punctuation and spelling.

"I, Roger Hartley Wiggins, sometime known as Adoniram Caldwell, having now resumed my proper name, and being about to marry, and having begun the construction of a habitation for myself wherein to end my days, truthfully set forth these matters:

"My father, Hiram Wiggins of Rhode Island, having supported the royalist cause in our late war for Independence, and angered by my friendliness to the patriots, and he, with ... brothers and sister having returned to England after the evacuation of Boston, I joined the Continental troops under General Putnam on Long Island, in July, 1776, serving in various commands thereafter, to the best of my ability, to the end.... My father has now returned to Rhode Island, and has, I learn, been making inquiries touching my whereabouts and condition, so that I have every hope that we may become reconciled. Yet as my services to the Country were against his wishes and caused so much harshness and heartache, and being now come into a part of the country where I am unknown, I am decided to resume my rightful name, that my wife and children may bear it and in the hope that I may myself yet add to it some honor....

"Nor shall my wife or any children that may be born to me, know from me ... (badly blurred.) Yet not caring to destroy my sword, which I bore with some credit, nor these testimonials of respect and confidence I received as Adoniram Caldwell at various times and from various personages of renown, both civilians and in the military service, I place them under my house now building, where I hope in God's care to end my days in peace. I would in like case make like choice again."

Ten lines following this were wholly illegible, but just before the date (June 17, 1789), and the signature, which was written large, was this:—

"God preserve these American states that they endure in unity and concord forever!"

We had all been moved by the reading of this long-lost letter, and Miss Octavia's voice had faltered several times. As I turned to Cecilia once or twice during the recital of the dead patriot's message, I saw tears brimming her eyes.

"Mr. Wiggins once told me that his great-grandfather had lived somewhere in Westchester County, but I fancy he had no idea that Hopefield was the identical spot," remarked Miss Octavia. "It seems incredible, and yet I dare say the hand of fate is in it."

"Oh, it's so wonderful; so beyond belief!" cried Cecilia, reverently folding the letter, which, I observed, she retained in her own hands.

"It's wonderful," added Miss Octavia promptly, taking the sword, which Pepperton had with difficulty drawn from its battered scabbard, "that even a discerning woman like me could have been so mistaken. I recall with humility that last Fourth of July, at Berlin, I reprimanded Mr. Wiggins severely because his family had not been represented in the war for American Independence. By the irony of circumstances it becomes my duty to present to him the very sword that his admirable great-grandfather bore in that momentous struggle. I shall, with his permission, place a bronze tablet on the outer wall of this house to preserve the patriot's memory."

Several copies of New York newspapers, half a dozen French gold coins, the miniature of a woman's face, which we assumed to be that of Roger Wiggins's mother or sister, were briefly examined; then by Miss Octavia's orders we carefully returned everything to the chest. Several packets of letters we did not open.

"Arnold," she said when we had closed the chest, "will you and Mr. Pepperton kindly carry that box to my room? No servant's hand shall touch it; and I shall myself give it to Mr. Wiggins at the earliest opportunity."

We had lost track of time in those hidden rooms, preserved by the whim of one man that the secret of another might be discovered, and found with surprise, after the chest had been carried to Miss Octavia's apartments, that it was after seven o'clock. We had been in the hidden rooms for more than three hours.

"We shall have much to talk about to-night, and I fancy we are all a good deal shaken. It's not often we receive a letter from a dead man, so we shall admit no callers to-night unless, indeed, Mr. Wiggins should chance to come," announced Miss Octavia. "The next time Hartley Wiggins visits this house he shall come as a conquering hero."

"I hope so," replied Cecilia brokenly.

We were still at dinner when the cards of Dick and the other suitors I had last seen at the Prescott Arms were brought in; but Wiggins made no sign, and I wondered.