CHAPTER X

MARY TUDOR

NORTHUMBERLAND had persuaded the dying King to pass over his sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, in favour of Lady Jane Grey, the grand-daughter of Henry VII. by the marriage of Mary, daughter of that King, with Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, as well as cousin to the late King Edward VI., and his own daughter-in-law; and the Privy Council, immediately after Edward’s death, had confirmed this measure. Northumberland’s plan, in which he had induced Edward to acquiesce, annulled both the Statute of Succession and the will of Henry VIII., for not only did it set aside both the late King’s sisters, but also the direct successors, to whom the crown would hereditarily fall, failing Henry’s daughters. These were the descendants of Henry’s eldest sister Queen Margaret, wife of James IV. of Scotland, who was represented by the girl Queen Mary Stuart, and, after her, by the descendants of Queen Margaret’s second marriage with the Earl of Angus, who were represented by Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, Queen Margaret thus being grandmother to both Queen Mary Stuart and Lord Darnley. Henry VIII. himself, however, had passed over Queen Margaret’s claims in his will, and had placed the children of his younger sister, Mary, Duchess of Suffolk, next to his daughter Elizabeth in the succession. The Duchess of Suffolk’s daughter—Lady Frances Brandon—had married Henry Grey, Marquis of Dorset, by whom she had had three daughters, of whom Lady Jane Grey was the eldest.[10] Dorset, who became Duke of Suffolk during the Protectorate, having been given his father-in-law’s dukedom, was a fervent follower of the Reformed faith, his children sharing his religious beliefs.

The Duchess of Suffolk, Jane’s mother, who was still alive at this time (1553) was passed over in Northumberland’s scheme, since he had succeeded in wedding the daughter to his fourth son, Guildford Dudley, his firm expectation being that as the future Queen’s father-in-law he would have the government of the realm in his own hands. But Northumberland’s ambitious dream was a short one, and the awakening was terrible.

At the time of Edward’s death Lady Jane Grey (Lady Jane Guildford as she should be called, but as was the case with Anne Askew, the paternal name has always been retained) was living at Sion House, a house belonging to her father-in-law, and here a deputation of the Council, headed by Northumberland, Suffolk, Pembroke, and others, went to pay their homage to the new Queen; on the 9th of July 1553, Lady Jane, or as she was now styled, Queen Jane, entered the Tower in state.

Jane Grey was but a girl of sixteen when the ambition of her relatives drew her from the retired and studious life that she loved, and forced her to take up all the perils and troubles that surround a throne. A more perfect creature, according to the unanimous testimony of her contemporaries, never gladdened God’s earth. Her brow was lofty, her features were delicate and refined, bearing a winning sweetness and bright cheerfulness which made all those who were fortunate enough to approach her, at once attached to her with a sentiment little short of devotion. Young as she was, her knowledge, even for those days when the daughters of great houses received an education which to us would appear almost encyclopædic, was prodigious. According to her tutors, Aylmer and Roger Ascham, Jane Grey knew Greek, Latin, French, and Italian, being able to both write and speak these languages. Besides, she knew something of Hebrew, Arabic, and even Chaldee. She was proficient in music, and could play upon a variety of instruments, singing to her own accompaniment. In addition to these accomplishments she wrote a beautiful hand—a rare talent for the time—and was a past mistress in the use of her needle.]

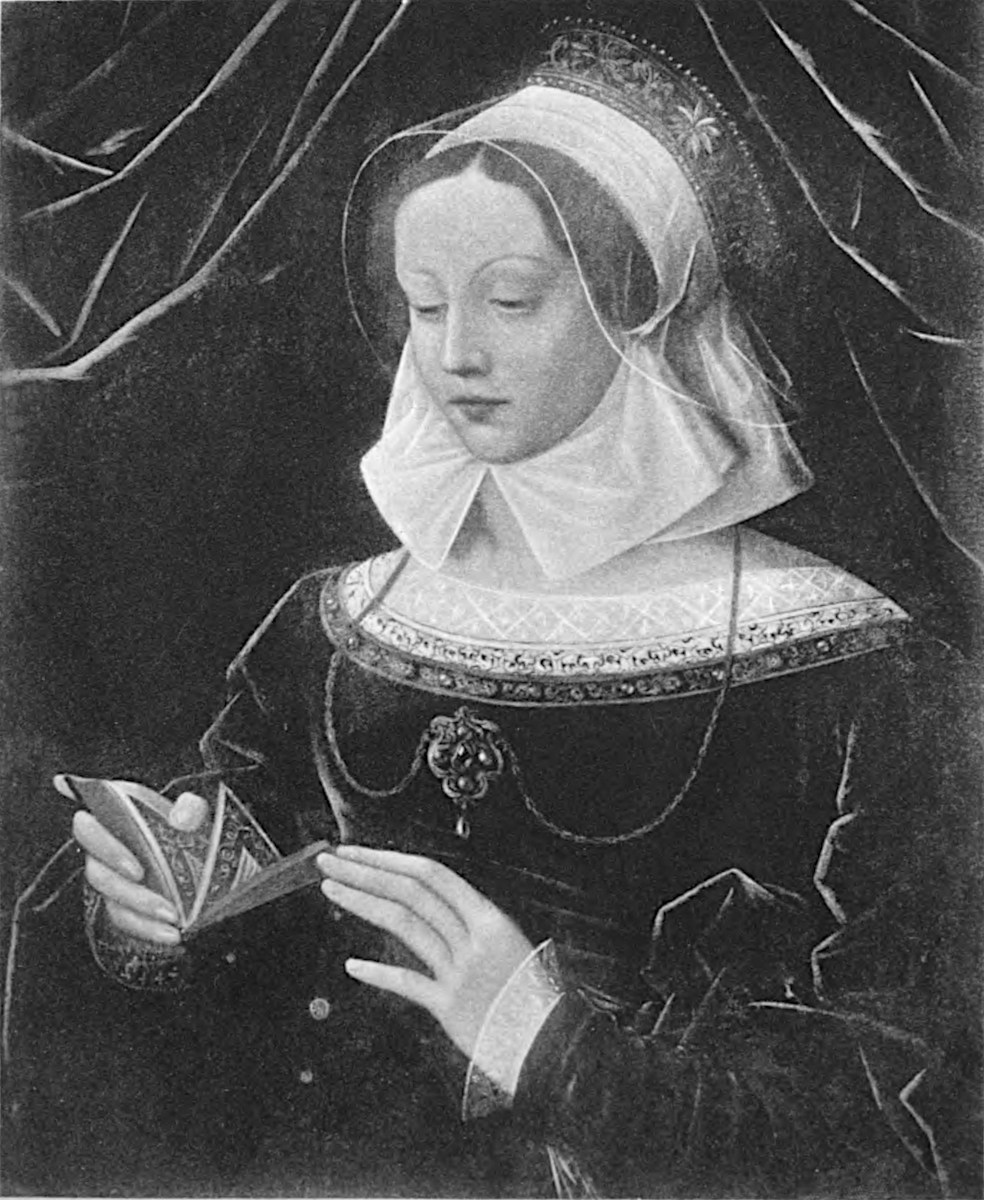

Queen Mary Tudor

(From a portrait at Latimer.)

Ascham’s account of his visit to Lady Jane at Broadgate has often been quoted, but it will bear quoting again:

“Before I went into Germany, I came to Broadgate in Leicestershire to take my leave of that noble lady, Lady Jane Grey, to whom I was exceedingly much beholden. Her parents the Duke and Duchess, and all the household, gentlemen and gentlewomen, were hunting in the park. I found her in her chamber reading the Phaedo of Plato in Greek, and that with as much delight as some gentlewomen would read a merry Tale of Boccaccio. After salutations and duty done, with some other talk, I asked her why she should lose such pastimes in the park. Smiling, she answered me, ‘All their sport in the park is but a shadow to the pleasure I find in Plato.’ However illustrious she was by fortune, and by royal extraction, these bore no proportion to the accomplishments of her mind adorned with the doctrines of Plato and the eloquence of Demosthenes.”[11]

With all her learning and her great accomplishments Lady Jane appears to have been entirely lacking in that provoking superiority and aloofness which, for want of a better word, we call “priggishness.” She was indeed that rare creature, a perfect woman in mind, and character, and person.

Most unwillingly did Lady Jane comply with Northumberland’s wishes. No crown could add to her happiness, which was not dependent upon this world’s state or station, nor one bestowed by the tinsel and glitter of earthly power or riches, but a “peace above all earthly dignities, a still and quiet conscience.” Jane Grey was not known to the Londoners, and Northumberland was heartily disliked because of his arrogance and overbearing manners, so it was not surprising that when they entered the city on the 10th of July, as the Duke himself said afterwards in deep chagrin, “not a single shout of welcome or God speed was raised as they passed through the silent crowd on their way to the Tower,” “With a grett company of lords and nobulls, and there was a shott of gunne and chambers as has nott been seen oft, between four and five of the clock” (Machyn). Jane Grey’s reign was not a long one.

On the 14th of July, Northumberland had left the Tower with his sons to take command of the troops that had been despatched against Mary, who, in the meantime, had been proclaimed Queen throughout London, whilst the fleet at Yarmouth had also declared for her, a warrant being issued for the arrest of Northumberland as a consequence. The Duke was at Cambridge when he was taken prisoner; he showed great cowardice, throwing his cap up in the air when he saw that his hopes were useless, crying, “God save Queen Mary!” and furthermore, when the Earl of Arundel, who had been sent by Mary, appeared on the scene, the Duke literally grovelled on his knees before him. But his tardy loyalty and his entreaties availed him little, for on the 25th of July he was lodged a prisoner in the Tower, where only a month before his word had been the supreme command. On the 18th of the following month he was arraigned for high treason in Westminster Hall, the Duke of Norfolk, who acted as Lord High Sheriff, breaking his wand upon giving sentence, which was a signal for the court to break up. Northumberland was taken back to the Tower and occupied a room in the Beauchamp Tower, where several inscriptions cut by his sons and himself are to be seen to this day.

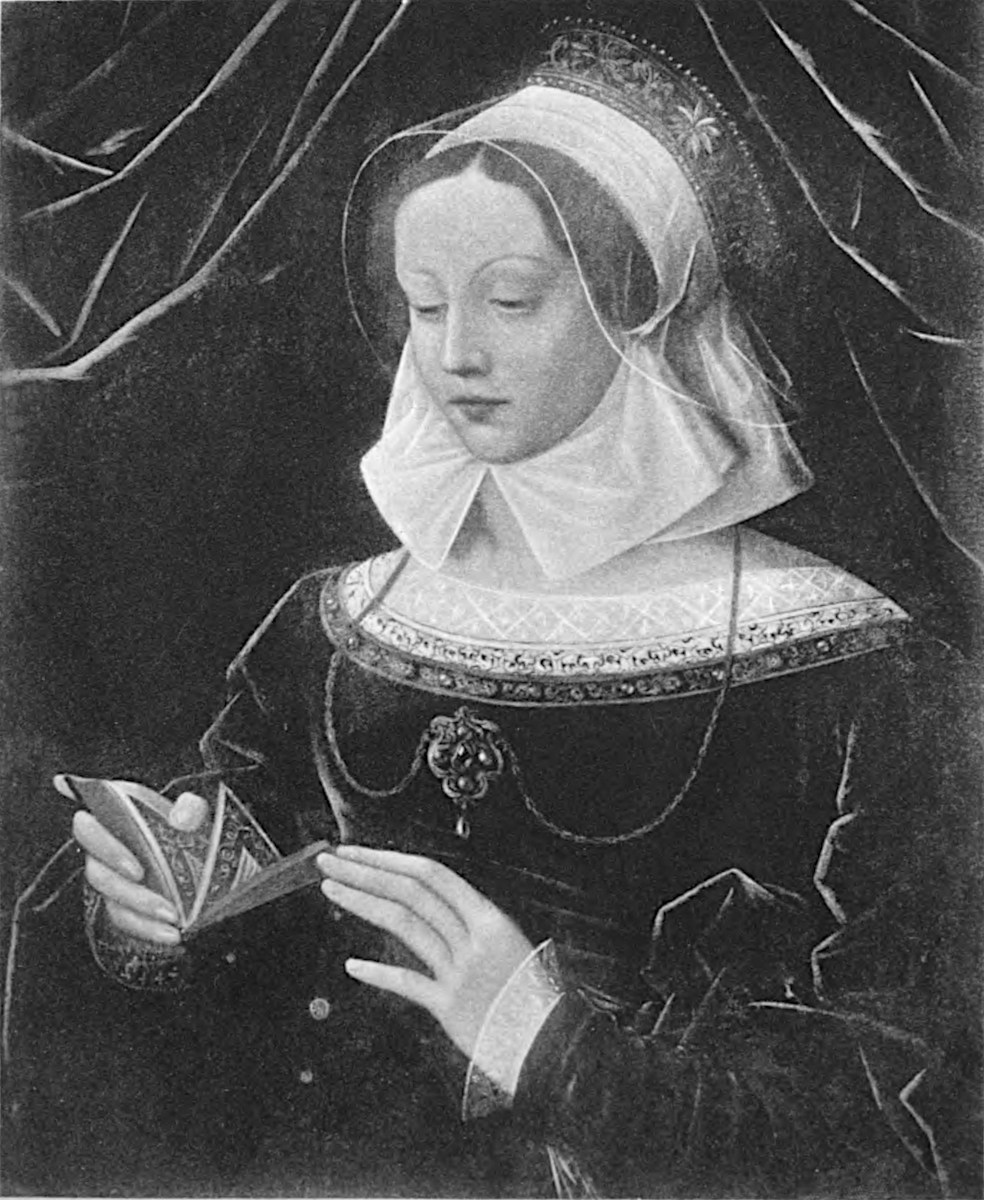

Lady Jane Grey

(From the original portrait at Madresfield Court by Lucas van Heere)

The day after he entered the Tower the Duke received a visit from Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, to whom he declared that he was a Roman Catholic at heart, and that he had always been a member of that faith. But although he “ratted” in his religion as well as in his politics, his facility of opinion was in vain. Gardiner was only too pleased to prove the Duke’s apostacy by a public ceremonial in which the changeable nobleman was the principal actor. Mass was said in the Chapel of the White Tower in which the Duke took part, and, that ended, he made a public confession, and a formal recantation of his former religion.

To return to Lady Jane Grey. When the news of Northumberland’s arrest at Cambridge reached the Tower, Lady Throckmorton, one of Lady Jane’s gentlewomen, on entering the Presence Chamber in the Palace, found that the canopy of state, and all the other ensigns of royalty had been removed. The nine days’ reign was at an end, and not unwillingly did Jane cease playing a part that she must have felt did not by right belong to her, and which must have been distasteful to her noble and upright nature. But a prison awaited both herself and her boy-husband, Guildford Dudley.

The tradition that Jane was imprisoned in the Brick Tower is incorrect, for at first she occupied a room in the Lieutenant’s House, now the King’s House, and later was removed to a house on the Green adjacent to the Lieutenant’s lodging, then occupied by the Gentleman gaoler of the Guard, Nathaniel Partridge by name. When Northumberland was led from the Beauchamp Tower to abjure his religion in the White Tower, Stowe writes that “Lady Jane looking through the windowe sawe the Duke and the reste going to the Church.” Jane’s feelings on learning Northumberland’s apostacy in the vain hope of saving his life, have been recorded in an anonymous MS. of the time, now in the British Museum (Harleian MSS. No. 194). The writer, who dined on the afternoon of the same day (29th August) with Partridge at the Gentleman gaoler’s house, met Lady Jane Grey there. After noting her graciousness to all present, he says that Lady Jane inquired whether Mass was being said in all the London churches, and on being answered that such was the case, she said that she did not think that so strange as the sudden conversion of the Duke, “for who would have thought,” she said, “that he would have done so?” On someone remarking that probably he had done so in order to obtain his pardon, “Pardon,” quoth she, “woe unto him! He hath brought me and our stock in most miserable calamity by his exceeding ambition. But for the answering that he hoped for his life by his turning, though other men be of that opinion, I utterly am not; for what man is there living, I pray you, although he had been innocent, that would hope of life in that case; being in the field against the Queen in person as general, and after his taking, so hated and evil-spoken of in the Commons? And at his coming into prison so wondered at, as the like was never heard at any man’s time. Should I, who am young in years, forsake my faith for the love of life? But God be merciful to us, for he sayeth who so denieth Him before man, he will not know him in His Father’s kingdom.” Whether Lady Jane spoke thus at Partridge’s dinner table is not possible of proof, “methinks the lady doth protest too much” for these to be the ipsissima verba of Lady Jane. Of her sorrow for Northumberland’s cowardice and smallness of spirit in allowing himself to be made an exhibition for the glorification of Queen Mary’s priests and creatures, there can be no doubt.

Lord Guildford Dudley

(From the original portrait at Madresfield Court by Lucas van Heere.)

The day after his recantation in the chapel of St John’s, Northumberland was beheaded. With him there went to the scaffold on Tower Hill, Sir John Gates and Sir Thomas Palmer, both these knights having been concerned in his conspiracy. Still clinging desperately to the hope of being pardoned at the last moment, Northumberland continued, as he was led to death, to profess his zeal for the Roman Catholic faith, and in the speech he made to the crowd from the scaffold declared that he was a fervent Papist. His example was not followed by his fellow-sufferers, both of whom died with manly fortitude, meeting their fate with a calm and unflinching demeanour. Others who had been implicated in Northumberland’s schemes, amongst whom were Lords Northampton, Warwick, and Ferrers, who had also been placed in the Tower, were pardoned, but their prisons were soon filled by fresh batches of captives. Of these new prisoners, the most important were Latimer, Bishop of Worcester, Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Ridley, Bishop of London, and the fortress was so full that these three prelates were obliged to share the same prison-chamber. On the 8th of March in the following year, the Bishops were taken from the Tower to their martyrdom at Oxford.

During the month of September in this year, Lady Jane was allowed to walk in the garden of the Palace, her husband, according to a chronicler of the time, also being given, with his brother, Lord Harry Dudley, what was called “the liberty of the leads” in the Beauchamp Tower. This meant that they were allowed to promenade on the outer passage running along the top of the wall which connects the Beauchamp with the Bell Tower.

Queen Mary had entered the Tower on the 3rd of August, practically in triumph, and there she held her court until after the funeral of her brother, the late king; Mary was again in the Palace of the fortress prior to her coronation, which took place on the 1st of October. On her first visit to the Tower in August she found, on reaching Tower Green, a group of State prisoners who awaited her arrival on their knees. Among these prisoners of the late reign was the old Duke of Norfolk; near him knelt the young and handsome Edward Courtenay, Earl of Devonshire, who had passed most of his short life in the Tower. Here, too, was the Duchess of Somerset, imprisoned at the same time as her husband, who had so lately been beheaded on Tower Hill. Here, too, knelt the Bishops of Winchester and Durham, Gardiner and Tunstall. To all of these Mary spoke with some emotion; she had come as their deliverer, and for once she appeared a woman as well as a Queen. On the eve of her coronation Mary was accompanied to the Tower by her half-sister Elizabeth.

It is strange to picture three such strangely different women as Queen Mary, Elizabeth Tudor, and Lady Jane Grey, together within the walls of the fortress at this time. The first a Queen, who has left behind her a more hateful memory than many far worse women among monarchs; the second, then but a powerless and semi-captive princess, whose future fame as a sovereign and ruler might well excite the envy of the mightiest potentate, but who, as a woman, lacked all that is best and most admirable in her sex; and the third, an uncrowned girl-queen of but seventeen summers, whose fate has called forth the love and pity of thousands, and whose brief life and death are the brightest and saddest in all history.

Mary’s coronation was marked by all the wonted splendour and elaborate ceremonial of such functions at such a period, and Holinshed has recorded that her head was so weighed down by her jewelled crown that “she was faine to bear up her head with her hand.” A month later the State trials commenced.

On the 13th of November a remarkable procession passed through the Tower Gate, and wended its way through the streets of the City to the Guildhall. Preceded by the axe, borne by the Gentleman Chief Warder, first came Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, followed by Lord Guildford Dudley and Lady Jane Grey, attended by two of her ladies. Lady Jane wore a dress of black from head to foot which is thus described by the chronicler Machyn:—“A black gown of clothe, turned downe, the cappe lyned with fese velvett, and edged about with the same; in a French hoode, all black, with a black habilment; a black velvet boke before her, and another boke in her hande open.” This account does not give a very clear idea of Lady Jane’s costume, but the curious reader, if he visits the National Portrait Gallery, will find a little full-face portrait of Lady Jane Grey as she then appeared, in which she is represented in this very dress, which she wore at her execution as well as during the trial.

The trial was held before the Lord Mayor of London, Thomas White, by special commission, the Duke of Norfolk presiding as High Steward. All the prisoners who pleaded guilty were attached for high treason, “for assumption of the Royal authority by Lady Jane, for levying war against the Queen, and conspiring to set up another in her room,” and Lady Jane was sentenced “to be burned alive on Tower Hill or beheaded as the Queen pleases,” the verdict being afterwards confirmed by Act of Parliament.[12] After sentence had been pronounced the prisoners were taken back on foot to the Tower.

During the few days that remained to Jane on earth, she was allowed to walk in the garden of the Palace, a three-cornered plot of ground enclosed on the north by the Queen’s Gallery, on the east by the Salt and Well Towers, and on the south and river side by the Ballium wall, which ran from the Well to the Cradle Tower. Sad and solitary must these gardens have been in those dark December days, and the heart of Jane Grey must have been very heavy when she recalled the days of her free and happy girlhood at Broadgate and Sion. Guildford Dudley was also allowed his daily walk on the wall passage between the towers, but he and his young wife were not to meet again on this side of eternity. At the last hour, however, permission was given that Dudley might bid farewell to Jane on his way to death on Tower Hill, but she, fearing the effect of such a supreme leave-taking for both, declined to avail herself of this sad opportunity.

If, after the trial, there had been any intention on Mary’s part to pardon Lady Jane Grey, such intention was frustrated by the action of Jane’s father, who, in an evil moment for himself and his children, joined in Wyatt’s rebellion. Baker, in his chronicle, writing of these events, says: “The innocent lady must suffer for her father’s fault, for if her father, the Duke of Suffolk, had not this second time made shipwreck of his loyalty, his daughter had perhaps never tasted the salt waters of the Queen’s displeasure, but now on a rock of offence she is the first that must be removed.”

A few days before the end, Jane wrote the following letters to her father, probably just before his own arrest, which took place on the 10th of February 1554. These letters bear no dates; this feminine fault of not dating her letters is the only one that can be found with gentle Lady Jane Grey.

“Father, although it has pleased God to hasten my death by you, by whome my life should rather have beene lengthened, yet I can soe patiently take it, that I yield God more hearty thanks for shortening my woful dayes, than if all the world had been given into my possession, my life lengthened at mine owne will. And albeit I am well assured of your impatient dolours, redoubled many wayes, both in bewaling your own woe, and especially as I am informed, my wofull estate, yet my deare father, if I may, without offence, rejoyce in my own mishaps, herein I may account myselfe blessed that washing my hands with the innocence of my fact, my guiltless bloud may cry before the Lord, Mercy to the innocent! And yet though I must needs acknowledge, that beyng constraynd, and as you know well enough continually assayed, yet in taking upon me, I seemed to consent, and therein greivusly offended the Queen and her lawes, yet doe I assuredly trust that this my offence towards God is so much the lesse, in that being in so royall estate as I was, mine enforced honour never mingled with mine innocent heart. And thus, good father, I have opened unto you the state wherein I presently stand, my death at hand, although to you perhaps it may seem wofull yet to me there is nothing that can bee more welcome than from this vale of misery to aspire, and that having thrown off all joy and pleasure, with Christ my Saviour, in whose steadfast faith (if it may be lawfull for the daughter so to write to her father) the Lord that hath hitherto strengthened you, soe continue to keepe you, that at the last we may meete in heaven with the Father, Sonn, and Holy Ghost.—I am, Your most obedient daughter till death,

“JANE DUDLEY.”

(Harleian MSS., and Nichols’ Memoirs of Lady Jane Grey.)

Here is another of her letters to her father:

“TO THE DUKE OF SUFFOLK.

“The Lord comforte your Grace, and that in his worde, whearin all creatures onlye are to be comforted. And thoughe it hathe pleased God to take away two of your children, yet thincke not, I most humblye beseache your Grace, that you have loste them, but truste that we, by leavinge this mortall life, have wonne an immortal life. And I for my parte, as I have honoured your Grace in this life, wyll praye for you in another life.—Your Grace’s humble daughter,

“JANE DUDLEY.”

IANA GRAYA DECOLLATA.

Regia stirps tristi cinxi diademate crines

Regna sed omnipotens hinc meliora dedit

H. Holbeen in.

E. V. Wÿngaerde ex

On the 8th of February Queen Mary’s favourite priest, Feckenham, had an interview with Jane in her prison, of which Foxe the martyrologist has recounted the details at great length; but, needless to say, Lady Jane remained unshaken in her firm faith, and in her attitude to the Reformed religion. It had been ordered that Guildford Dudley should die on Tower Hill, whilst Jane suffered within the walls the same day, Monday the 12th of February being fixed for the double execution. On the eve of this day Jane was sufficiently calm to write a long “exhortation” for the use of her sister, Catherine Grey, writing it in the blank pages of a manuscript on vellum, entitled “De Arte Moriundi.” This exhortation is as full of devotion and perfect faith in the mercy of her Saviour as were the beautiful lines she wrote to her father.

Although Guildford wished for a last interview with Jane on the morning of their execution, she was firm in deciding that “the separation would be but for a moment” as she is reported to have said, adding, that if their meeting could benefit either of their souls she would be glad to see her husband, but she felt it would only add a fresh pang to their deaths, and they would soon be together in a world where there would be no more death or separation. The last moments of this unfortunate lady were inexpressibly tragic. About ten o’clock on the morning of the 12th of February, Guildford Dudley was led forth from his prison to the scaffold on Tower Hill, being met at the outer gate by Sir Thomas Offley, and passing under his wife’s windows as he crossed the Green. Bidding farewell to Sir Anthony Brown and Sir John Throgmorton, Guildford met his fate with high courage. His body was brought back to the Tower in a handcart, the head being placed in a cloth; and looking forth from her prison, Lady Jane was suddenly confronted with the remains of what a few minutes before had been her husband. But nothing could shake her fortitude, as the following account, taken from the Chronicles of Queen Jane and Queen Mary, shows:—

“By this tyme was ther a scaffolde made upon the grene over agaynst the White Tower for the saide Lady Jane to die upon.... The saide Lady being nothing at all abashed, neither with feare of her own deathe, which then approached, neither with the ded carcase of her husbande, when he was brought into the chappell, came forthe the Lieutenant (who was Sir John Bridges, afterwards Lord Chandos of Sudeley) leading hir, in the same gown wherein she was arrayned, hir countenance nothing abashed, neither her eyes mysted with teares, although her two gentlewomen Mistress Elizabeth Tylney and Mistress Eleyn wonderfully wept, with a boke in hir hand, whereon she praied all the way till she came to the saide scaffolde, whereon when she was mounted, this noble young ladie, as she was indued with singular gifts both of learning and knowledge, so was she as patient and mild as any lamb at hir execution.”

After praying for her enemies and herself, Jane turned to the priest Feckenham and inquired whether she could repeat a Psalm, and he assenting she repeated the fifty-first. She then handed her gloves and her handkerchief to one of her ladies, giving the book she had brought, to Thomas Bridges for him to give to his brother, Sir John. On a blank page of this book[13] she had written:

“For as mutche as you have desyred so simple a woman to wrighte in so worthye a booke, good mayster Lieuftenante, therefore I shall as a frende desyre you, and as a christian require you, to call uppon God to encline your harte to his lawes, to quicken you in his wayes, and not to take the worde of trewethe utterlye oute of youre mouthe. Lyve styll to dye, that by deathe you may purchas eternall life, and remember howe the ende of Mathusael, whoe as we reade in the scriptures was the longeste liver that was a manne, died at the laste; for as the precher sayethe, there is a tyme to be borne, and a tyme to dye: and the daye of deathe is better than the daye of oure birthe.—Youres, as the Lord knowethe, as a frende,

“JANE DUDDELEY.”

The chronicle of her death continues thus:

“Forthwith she untied her gowne. The hangman went to her to have helped her off therwith, then she desyred him to let her alone, turning towards her two gentlewomen, who helped her off therwith, and also her frose paste” (this most singular term means a matronly head-dress) “and neckercher, geving to her a fayre handkercher to knytte about her eyes. Then the hangman kneled downe, and asked her forgiveness whom she forgave most willingly. Then he willed her to stand upon the strawe, which doing she sawe the blocke. Then she sayd I pray you despatche me quickly. Then she kneled downe saying, ‘Will you take it off before I lay me downe?’ And the hangman answered her, ‘No, madame.’ She tied the kercher about her eyes. Then feeling for the block, saide ‘What shal I do, where is it?’ One of the standers by guyding her therunto, she layde her head downe upon the block, and stretched forth her body, and said, ‘Lord, into thy handes I commende my spirite,’ and so she ended” (Holinshed, and Chronicles of Queen Jane and Queen Mary).

No wonder that good old Foxe could not refrain from shedding tears when he recounted this tragedy, but sad as is the story of Jane Grey’s death, her life and its close are amongst England’s glories. Heroines are rare in all times and in all countries, but in Jane Grey we can boast of having had one of the truest and noblest of women, a perpetual legacy to us for all time. The name of Jane Grey shines out like some brilliant star amid the storm wrack that surrounds it on every side. Amidst all the bloodshed, crime, and cruelty of this sanguinary age of English history to read of that gentle spirit, that marvellously gifted, and most noble, pure, and gifted being, is like coming suddenly upon a beautiful white lily in the midst of a tangle of loathsome weeds.

Fuller, of “English Worthies” fame, has, in his quaint manner, summed up Jane Grey’s life in these words: “She had the birth of a Princess, the life of a saint, yet the death of a malefactor, for her parent’s offences, and she was longer a captive than a Queen in the Tower.” Both Jane and her husband were buried in the chapel of St Peter’s of the Tower.

The news of the Queen’s approaching marriage with Philip of Spain set half the country in a blaze. The men of Kent rose, headed by Sir Thomas Wyatt, as did those of Devon, led by Sir Peter Carew. As we have already seen, the Duke of Suffolk headed another rising in Leicestershire, but he was soon defeated and captured, and together with his brother Lord John Grey was taken to London and imprisoned in the Tower, on the 10th of February, two days before his daughter, Jane Grey’s, execution. It was only four months before, that Suffolk had received his daughter at the fortress as Queen of England, and he must have felt more than the bitterness of death at the thought that it was owing to his conduct in again leading an armed force against Queen Mary that Jane’s life, as well as his own, were sacrificed.

Five days after Jane had met her death on a scaffold which stood close to her father’s prison, he himself was taken to his trial at Westminster Hall. It was noted that when he left the fortress the Duke went “stoutly and cheerfully enough,” but that on his return when he landed at the water gate, “his countenance was heavy and pensive.” This is scarcely to be wondered at for he had been sentenced to death, and was beheaded on Tower Hill on the 23rd of the same month.

In the brief speech which he delivered to the people before his death the unfortunate Duke admitted the justice of his sentence, saying, “Masters, I have offended the Queen and her laws, and thereby I am justly condemned to die, and am willing to die, desiring all men to be obedient; and I pray God that this my death may be an example to all men, beseeching you all to bear me witness that I die in the faith of Christ trusting to be saved by his blood only, and by no other trumpery, the which died for me, and for all men that truly repent and steadfastly trust in him. And I do repent, desiring you all to pray to God for me that when you see my head depart from me, you will pray to God that he may receive my soul.”

Of Suffolk, Bishop Burnet writes; “That but for his weakness he would have died more pitied, if his practices had not brought his daughter to her end.”

Although it is probable that Suffolk’s body was buried in St Peter’s Chapel, his head is believed to be in the Church of the Holy Trinity in the Minories, a building which is within the ancient liberties of the Tower. The Duke’s town house was the converted convent of the church of the nuns of the order of Clares, so called after their foundress Santa Clara of Assisi. They were known as the “Sorores Minores,” whence the name of the district—the Minories. This building had been made over to Suffolk by Edward VI., and the present church of the Holy Trinity actually stands upon the site of the old convent chapel. This interesting edifice is now (1899) threatened with destruction, and in a few years it is extremely probable that the ground upon which it stands will be covered with warehouses or buildings connected with the London and North-Western Railway.

The head was found half-a-century ago in a small vault near the altar, and as it had been placed in sawdust made of oakwood, it is quite mummified, owing to the tannin in the oak. There is the mark of the blow of a sharp