CHAPTER XI

QUEEN ELIZABETH

THE important position occupied by the Tower at the commencement of the reign of Elizabeth, and its connection with all branches of State affairs is shown by the great antiquary of that reign, John Stowe, who says it was “The citadel to defend and command the city, a royal palace for assemblies and treaties, a State prison for dangerous offenders, the only place for coining money, an armoury of warlike provisions, the treasury of the Crown jewels, and the storehouse of the Records of the Royal Courts of Justice at Westminster.”

Elizabeth’s imprisonment, four years previous to her accession, had not left kindly impressions of the Tower, and although her first visit to any royal palace after she became Queen on 28th November 1558, was to the fortress, she did not take up her abode there for any length of time, remaining at Somerset House, and at the palace at Whitehall, until Mary’s funeral had taken place.

Three days, however, before her coronation, Elizabeth entered the Palace of the Tower, the crowning taking place on Sunday the 15th January 1559. Elizabeth’s love of show and magnificence must have been amply gratified by the great pageant in which she was the central figure, the procession from the Tower to the Abbey being more brilliant than any in the history of the English Court.

Seated in an open chariot which glittered with gold and elaborate carvings, Elizabeth, blazing with jewels, passed through streets hung with tapestry and under triumphal arches, the ways being lined with the City companies in their handsome liveries of fur-lined scarlet. In Fleet Street a young woman, representing Deborah, stood beneath a palm tree, and prophesied the restoration of the House of Israel in rhymed couplets, whilst Gog and Magog received her Majesty at Temple Bar.

Although the horrors of Smithfield and other auto-da-fés had ceased with Mary’s reign, religious persecution on the part of the Reformers was all too rampant under Elizabeth. The new Queen inherited far too much of her father’s nature to brook any kind of opposition to her wishes. She was a strange compound of the greatest qualities and the meanest failings. Endowed with prodigious statecraft, her vanity was no less immense, and her jealousy of all who came between herself and those whom she liked and admired, caused her not only to commit acts of injustice, but actual crimes. Her mind, which had a grasp of affairs of state and policy that would have done credit to a great statesman, had also many of the weaknesses and pettinesses of a vain, frivolous, and foolish woman. Elizabeth’s conduct towards the unfortunate Catherine Grey, her cousin, and the younger sister of Lady Jane, shows the jealousy of her character in its worst light.

It was to Catherine Grey that Lady Jane, on the eve of her execution, had sent the book in which she had written the “exhortation.” Lady Catherine had married Lord Herbert of Cardiff, but had been separated from him, being known by her maiden name. In 1560 she had met at Hanworth, the house of her friend the Duchess of Somerset, the latter’s eldest son, Lord Hertford, the result of this meeting being that an affection had sprung up between them which was followed by a secret marriage, as it was known that Elizabeth would not approve of the match. The only confidante was Hertford’s sister, Lady Jane Seymour, and the young couple—he was only twenty-two and she twenty—were married as secretly as possible.

Catherine, accompanied by Lady Jane Seymour, walked from the Palace at Whitehall—they were both ladies-in-waiting on the Queen—along the river side at low tide, to Lord Hertford’s house near Fleet Street. Here the marriage took place, but, by a strange want of foresight or by some strange oversight, neither of the contracting parties were afterwards able to remember the name of the clergyman who married them, “with such words and ceremonies, and in that order, as it is there” (the Prayer Book) “set forth, he placing a ring containing five links of gold on her finger, as directed by the minister.” The Hertfords afterwards described the minister as being of the middle height, wearing an auburn beard and dressed in a long gown of black cloth.

The newly-wed Lady Hertford was too nearly related to the Queen to be allowed to please herself with regard to whom she married, and when the time drew near when further concealment was impossible, the poor lady was in a terrible dilemma. Lord Hertford appears to have been the more timid of the two, for when he found that his wife was about to become a mother, he, dreading the Queen’s anger, fled to France, leaving poor Lady Hertford to bear the brunt of Elizabeth’s imperious temper alone. To complicate matters, Lady Jane Seymour, who throughout this adventure had been the young couple’s only friend, died early in the year 1561. When concealment was no longer possible, Lady Hertford threw herself upon the mercy and generosity of her terrible mistress. But on being informed of what had happened, Elizabeth’s anger knew no bounds, and poor Lady Hertford was at once sent to the Tower, where shortly after her arrival her child was born. Hertford now returned to England, and was promptly arrested, being also imprisoned in the Tower, where he remained for many a long year.

In the meantime the Queen declared that the marriage was illegal, and a Commission sitting upon the matter, consisting of the Primate, Parker, and Grindal, Bishop of London, declared it null and void. Matters might perhaps have been arranged had not another child been born to the Hertfords. When Elizabeth heard that Lady Hertford had been again confined, her rage was ten times greater than before. She summarily dismissed the Lieutenant of the Tower, Sir Edward Warner, for having allowed the unfortunate couple to meet again, and ordered Hertford to be brought before the Star Chamber, when he was heavily fined and sent back to his prison, where he remained for the next nine years.

In the Wardrobe accounts of the Tower in the Landsdowne MSS. at the British Museum, there is a list of the furniture supplied to Lady Hertford in her prison. Tapestry and curtains are mentioned, also a bed with a “boulster of downe,” as well as Turkey carpets and a chair of cloth of gold with crimson velvet, with panels of copper gilt and the Queen’s arms at the back. All this furniture, which sounds very magnificent, is noted by the Lieutenant of the Tower as being, “old, worn, broken, and decayed,” but in a letter he addressed to Cecil he wrote that Lady Catherine’s monkeys and dogs had helped to damage it. One is glad to know that the poor lady was allowed her pets, however harmful to the furniture, to amuse her in her lonely prison, where she lingered for six years, dying there in 1567.

Considering Elizabeth’s own experience of the amenities of imprisonment in the Tower one would have thought that she might have shown more mercy to her unfortunate kinswoman. In later years Hertford consoled himself by marrying twice again, both his second and third wives being of the house of Howard. His marriage with Catherine Grey was only made valid in 1606, when the “minister” who had performed the ceremony was discovered, a jury at Common Law proving it a bonâ fide transaction, and making it legal.

Another unfortunate lady who was a victim of Elizabeth’s implacable jealousy was Lady Margaret Douglas, who married the Earl of Lennox. The Countess, like Lady Catherine Grey, was one of Elizabeth’s kinswomen, and owing to her near relationship her actions were a source of continual suspicion to the Queen. Lady Lennox suffered three imprisonments in the Tower; as Camden has it, she was “thrice cast into the Tower, not for any crime of treason, but for love matters; first, when Thomas Howard, son of the first Duke of Norfolk of that name, falling in love with her was imprisoned and died in the Tower of London; then for the love of Henry, Lord Darnley, her son, to Mary, Queen of Scots; and lastly for the love of Charles, her younger son, to Elizabeth Cavendish, mother to the Lady Arabella, with whom the Queen of Scots was accused to have made up the match.” In the description of the King’s House, reference has been made to the inscription in one of its rooms recording the imprisonment of the Countess of Lennox there; that inscription refers to her second incarceration in the Tower in 1565. Few women can have suffered so severely for the love affairs of their relatives as this unfortunate noblewoman.

The long struggle between Elizabeth and Mary Stuart, which only closed on the scaffold at Fotheringay in 1587, brought many prisoners of State to the Tower. Some of the earliest of these belonged to the de la Pole family, two brothers, Arthur and Edmund de la Pole, great-grandchildren of the murdered Duke of Clarence, being imprisoned in the Beauchamp Tower in 1562, on a charge of conspiring to set Mary Stuart on the English throne. There are, as we have seen, several inscriptions in the prison chamber of the Beauchamp Tower bearing the names of the two brothers. These two de la Pole brothers ended their lives within their Tower prison, whether guilty or not who can tell?

Few can realise the terrible and constant danger in which Elizabeth lived from the claim of Mary Stuart to the throne of England. Compared with France, England at the close of Mary Tudor’s reign was only a third-rate power, and never had the country sunk so low as a martial power as in the last years of her disastrous rule. We had no army, no fleet, only a huge debt, whilst the united population of England and Wales was less than that of London at the present time.

Motley has conjectured that at that time the population of Spain and Portugal numbered at least twelve millions. Spain possessed the most powerful fleet in the world, an immense army, with all the wealth of the Netherlands and the Indies wherewith to maintain them; consequently, when difficulties arose between France and England, Philip trusted that to save herself England would become a firm ally of Spain. But the Spanish monarch had left out of his reckoning the magnificent courage of England’s Queen, and the indomitable pluck, and bull-dog determination of her subjects to hold their own. All this should be remembered when the stern repression of all and every kind of conspiracy is brought against Elizabeth and her principal advisers, of whom Walsingham and Burleigh were the foremost. It was a desperate position, only possible of being defended and upheld by desperate means. The horrors perpetrated by the Romish bishops in the name of religion whilst Mary Tudor reigned, had given the English but too vivid a suggestion of the fate that would befall their country if the King of Spain were again to become its ruler, either as conqueror or as King-consort. This terror was the principal cause of the passionate tide of patriotism that under Elizabeth stirred our glorious little island to its very foundations, and had it not been for the detestation of foreign rule there would not have been that universal rallying round the Queen and country in the hour of danger, which was the marked feature of our people during that courageous woman’s reign.

A suspicion of conspiracy was sufficient in those days, electrical with perils for the Queen and the country, and on the 11th of October 1569 Thomas Howard, fourth Duke of Norfolk, the son of the ill-fated Surrey, and the grandson of the old Flodden duke, was brought a prisoner to the Tower on the charge of high treason, his intended marriage with Mary of Scots constituting the charge against him. In the following month the Queen thus directed Sir Henry Neville to attend to Norfolk’s safekeeping in the Tower. “The Lieutenant is permitted to remove the Duke to any lodging in the Tower near joining to the Long Gallery, so as it be none of the Queen’s own lodgings; and to suffer the Duke to have the commodity to walk in the gallery, having always of course the said Knollys in his company” (Hatfield Calendar of State Papers). Owing to the plague which raged in London in the following year, Norfolk was allowed to leave the Tower for his own home at the Charter House, still a prisoner; but he was soon back again in the fortress, a correspondence which he had carried on with Mary Stuart’s adherents having been discovered. Others implicated in the undoubted conspiracy to set Mary on the throne, were the Earls of Arundel and Southampton, Lord Lumley, Lord Cobham, his brother Thomas Cobham, and Henry Percy; these were all arrested. On his return to the Tower, Norfolk was confined in the Bloody Tower. About this time a batch of letters, written by a Florentine banker named Ridolfi to the Pope and to the Duke of Alva, on the perpetually recurring subject of Mary’s succession to the English throne after Elizabeth’s dethronement, were intercepted by Elizabeth’s government, with the result that a fresh batch of prisoners, with the Bishop of Ross, Sir Thomas Stanley, and Sir Thomas Gerrard amongst them, entered the fortress. These letters disclosed a conspiracy which was known under the name of the Italian Ridolfi, its prime instigator. Ridolfi, who was a resident in London, had crossed over to the Netherlands, where he had seen the Duke of Alva, informing that Spanish general that he had been commissioned by a large number of English Roman Catholic noblemen to send over a Spanish army to drive Elizabeth from the throne, and place Mary Stuart in the sovereignty in her stead. The Duke of Norfolk would then marry Mary, and by these means the English would return to the benign sway of the Holy Father, and become the faithful subjects of the gentle Philip. Alva had suggested that Elizabeth should be got rid of before he himself came to London with his army, Philip entirely agreeing with his general as to the necessity for her removal.

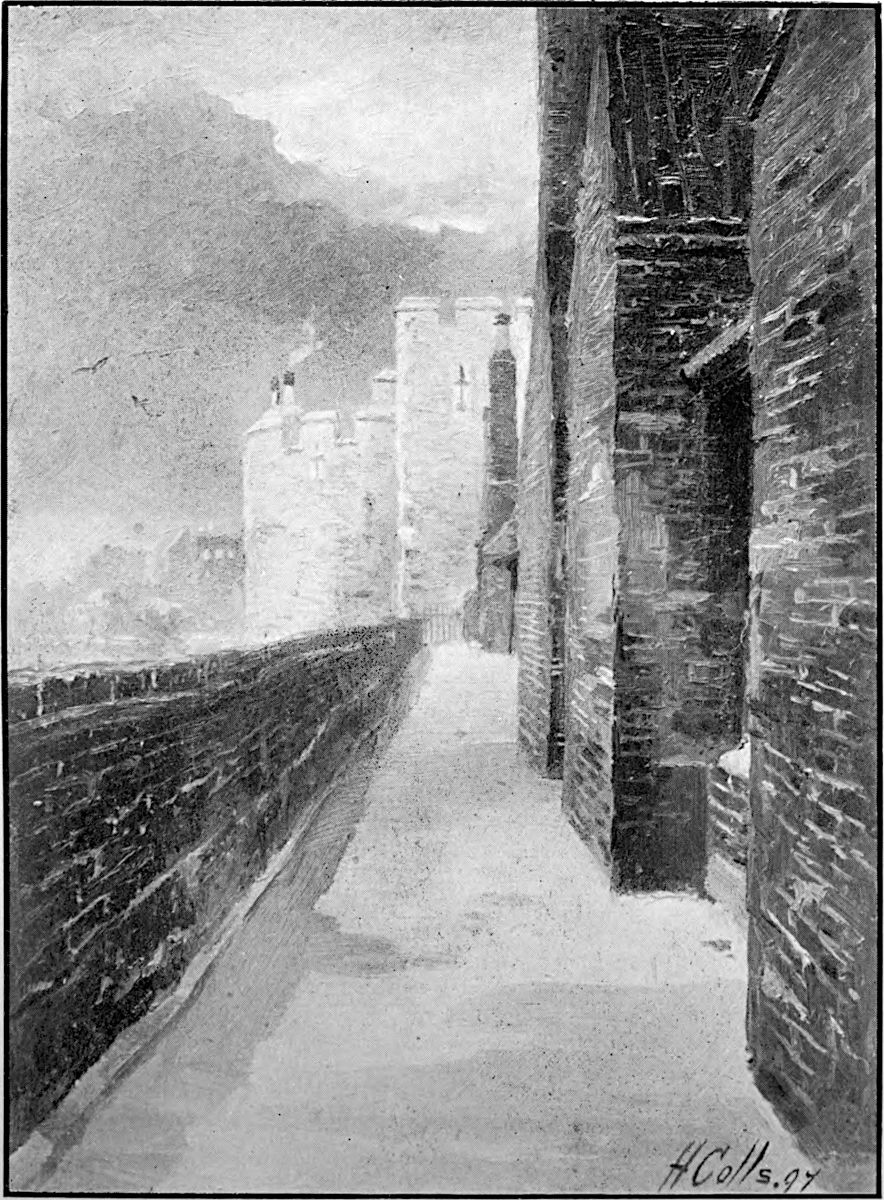

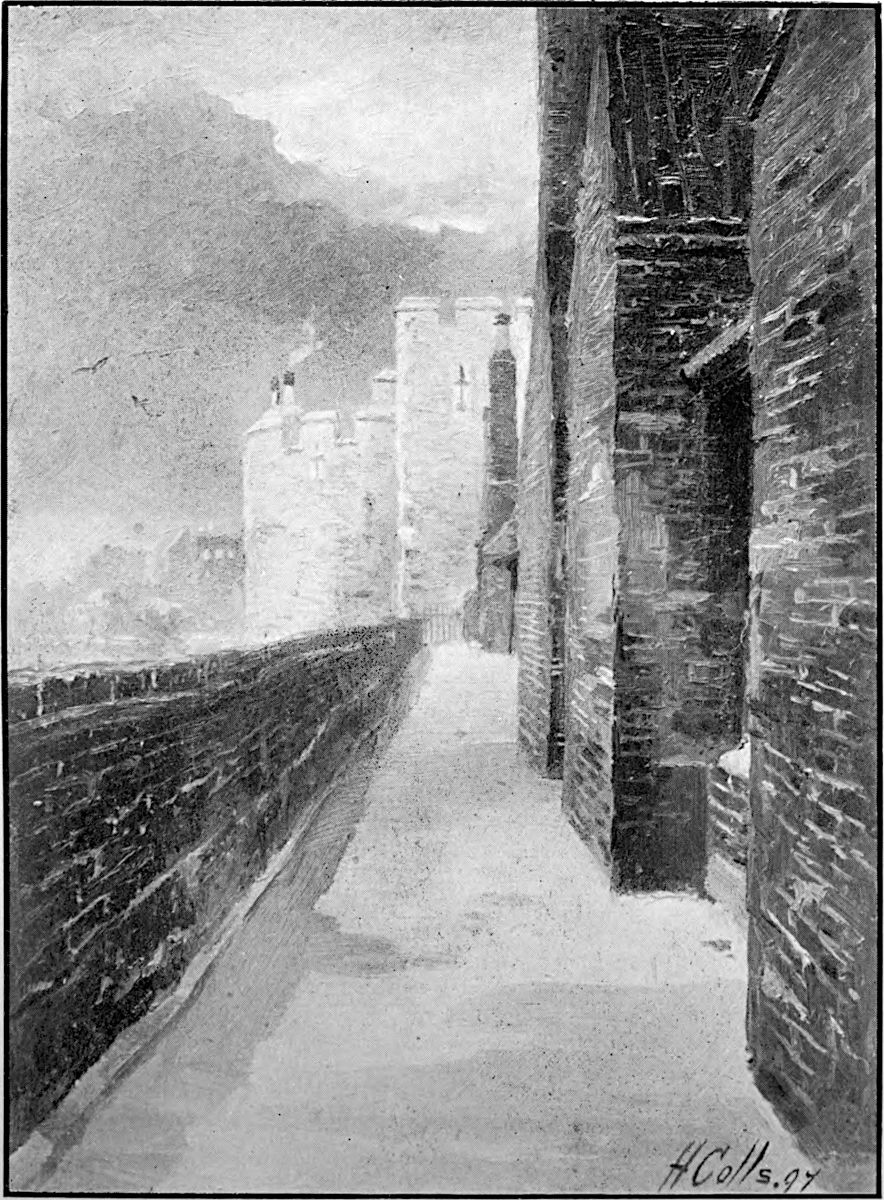

Queen Elizabeth’s Walk, from the Curfew Tower to the Beauchamp Tower

The mere chance of a packet of letters being intercepted not only saved Elizabeth’s life, but probably England as well from a terrible disaster.

The Ridolfi Plot conspirators were distributed in the various prisons of the fortress, in the Beauchamp and the Salt Towers, and in the Cold Harbour, much of the information regarding the conspiracy having been obtained from a young man called Charles Bailly, who was seized at Dover on his way to the Netherlands with a packet of treasonable letters. He was brought back to London, placed in the Tower and tortured, whereupon he confessed the names of several other persons implicated. Bailly left several inscriptions on the walls of the Beauchamp Tower where he was imprisoned.

On the 16th of January 1572 the Duke of Norfolk was taken from the Tower to Westminster to undergo his trial. He was charged with having entered into a treasonable conspiracy to depose the Queen and to take her life; of having invoked the aid of the Pope to liberate the Queen of Scots, of having intended to marry her, and for having attempted to restore Papacy in the realm.

The Duke, who was not allowed counsel, pleaded in his own behalf, attempting to prove that his intended marriage with Queen Mary of Scots would not have affected the life or throne of Elizabeth. “But,” replied the Queen’s Sergeant, Barham, “it is well known that you entered into a design for seizing the Tower, which is certainly the greatest strength of the Kingdom of England, and hence it follows, you then attempted the destruction of the Queen.” By his own letters to the Pope the Duke stood condemned, as well as by those written by him to the Duke of Alva, and to Ridolfi, in addition to others written from the Tower to Queen Mary by the Bishop of Ross. Norfolk was accordingly condemned, but Elizabeth appears to have wavered regarding the signing of his death warrant, for the Duke was her cousin. At length, however, the House of Commons insisted that the Duke must die for the safety of the State, and Elizabeth signed the warrant, and the 2nd of June was fixed for his execution.

The Duke wrote very appealingly to the Queen for pardon, beseeching her to forgive him for his “manifold offences” and “trusts that he may leave a lighter heart and a quieter conscience.” He desired Burghley to act as guardian to his orphaned children, and concluded his letter thus: “written by the woeful hand of a dead man, your Majesty’s most unworthy subject, and yet your Majesty’s, in my humble prayer, until the last breath, Thomas Howard.”

Fourteen years had passed since anyone had been executed on Tower Hill. The old wooden scaffold had fallen into decay, and it was found necessary to build a new one. Compared with former reigns the fact of no execution having taken place amongst the State prisoners for such a length of time does credit to Elizabeth’s clemency, Norfolk being the first to die for a crime against the State during her long reign. The Duke has found apologists among historians, and has been regarded as a hardly-used victim of Elizabeth and her Ministers. But his treason to the Queen he had sworn to obey and defend was proved beyond all manner of doubt, and his particular form of treason was the worst, having no possible extenuation, since he plotted for the admission of a foreign army into the realm, composed of the most bloodthirsty wretches that ever desecrated a country, and led by a general whose cruelty resembled that of a devil, and has left him infamous for all time.

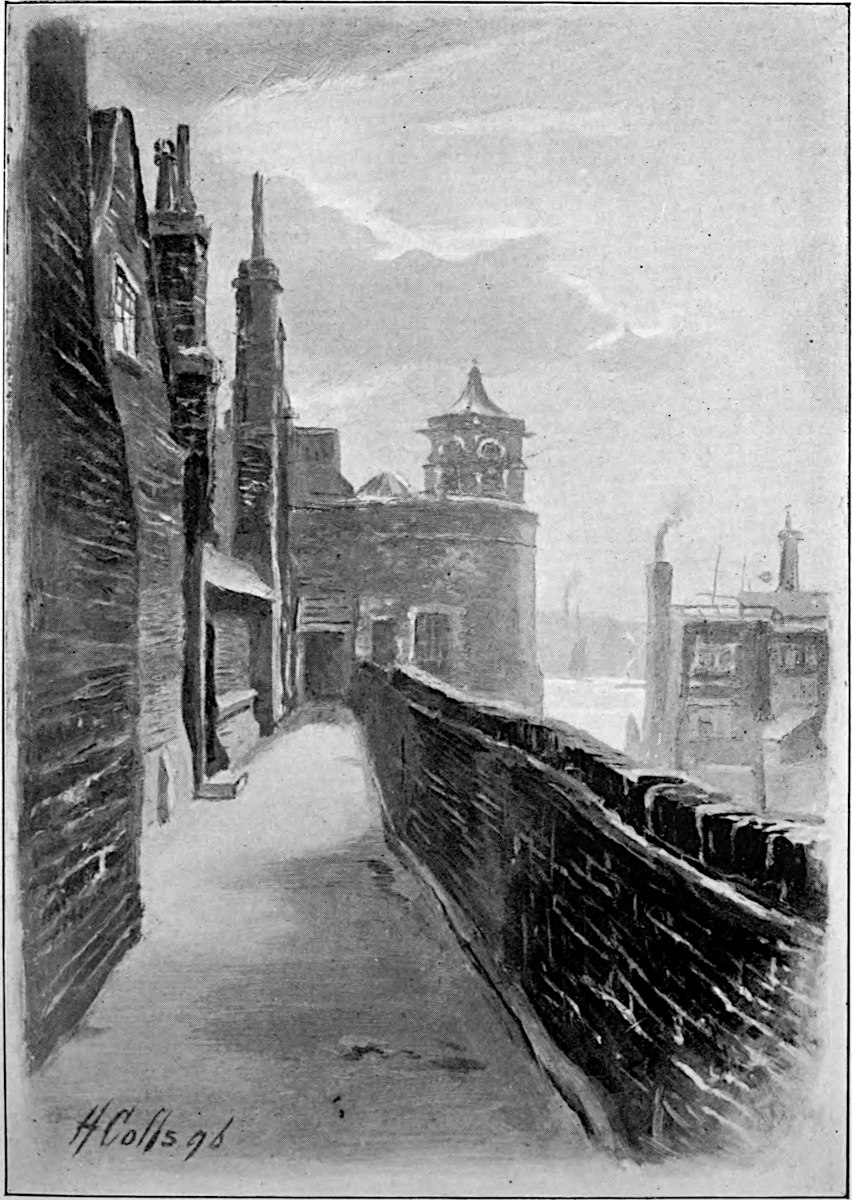

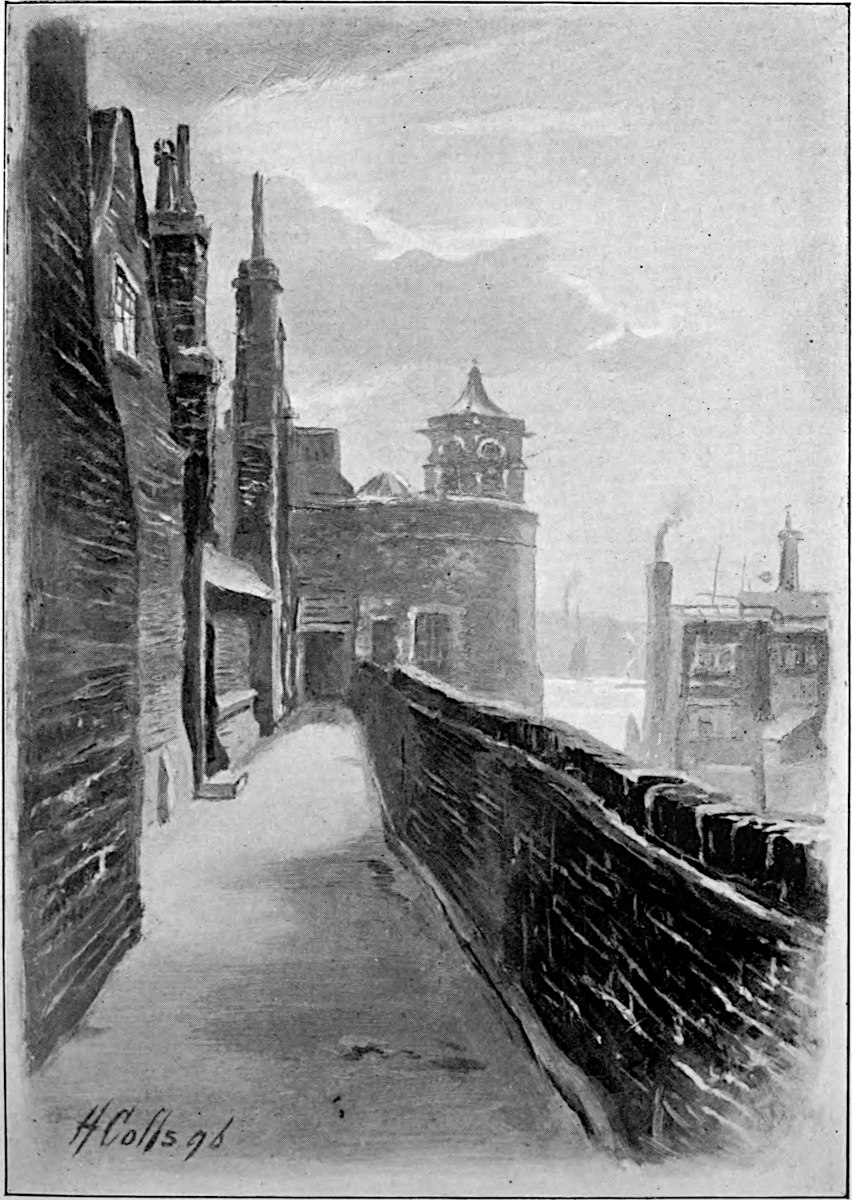

Queen Elizabeth’s Walk, from the Beauchamp Tower to the Curfew Tower

Norfolk merited his doom, and the more illustrious his name and rank, the more grievous his fault. As to finding cause for pitying him on the ground of his attentions to Queen Mary, that, too, seems unnecessary. The Duke had never seen the Scottish Queen, nor is he likely to have felt much affection for a woman who had been implicated in her husband’s murder, and had allowed herself to be carried off by that husband’s assassin. Norfolk was accompanied to the scaffold by his old friend, Sir Henry Lee, the Master of the Ordnance.[14] Norfolk refused to have his eyes bandaged, and begging all present to pray for him, met his fate with calmness. “His head,” writes an unknown chronicler (Harleian MSS.), “with singular dexteritie of the executioner was with the appointed axe at one chop, off; and showed to all the people. Thus he finyshed his life, and afterwards his corpse was put into the coffyn; appertaninge to Barkynge Church, with the head also, and so was caryed by foure of the lyeutenant’s men and was buried in the Chappell in the Tower by Mr Dean (Dr Nowell) of Paules.” The Duke’s last words are worthy of remembrance. While reading the fifty-first Psalm, when he came to the verse, “Build up the walls of Jerusalem,” he paused an instant, and then said, “The walls of England, good Lord, I had almost forgotten, but not too late, I ask all the world forgiveness and I likewise forgive all the world.”

One of Queen Mary Stuart’s most devoted adherents was John Leslie, Bishop of Ross, who, like Norfolk, had been deeply implicated in the Ridolfi conspiracy, and had been imprisoned in the Bell Tower. When tried for treason, the Bishop pleaded that being an Ambassador he was not liable to the charge; he was kept for two years in the Tower and then he was banished.

Priests, and especially those who were Jesuits, were very harshly dealt with at this time, the utmost rigour being shown to all who opposed the Queen’s acts or intentions. We have one instance of this in the fate which befell that eminent theologian, John Stubbs, who had written a pamphlet against the proposed marriage of Elizabeth with the Duke of Anjou, the brother of the King of France, Charles IX., and himself afterwards King of that country under the title of Henry III. Dr Stubbs was sentenced to have his right hand cut off by the hangman, the unlucky printers of his pamphlet being treated in the same barbarous manner. Immediately his hand was cut off, Stubbs raised his cap with the other, shouting, “God save the Queen!”; this truly loyal incident was witnessed by the historian Camden.

Besides the penalty of losing the right hand for writing or printing matter which might be disapproved by the Queen or her Council, the same punishment was awarded to any person striking another within the precincts of the royal palaces, of which the Tower was one. Peter Burchet, a barrister of the Middle Temple, had been committed to the Tower in 1573 for attempting to kill the celebrated Admiral Sir John Hawkins, whom he had mistaken for Sir Christopher Hatton. During his imprisonment he killed a warder, or attendant, by knocking him on the head with a log of wood taken from the fire. For this he was condemned to death, but before being hanged at Temple Bar, his right hand was cut off for striking a blow in one of the royal palaces. At this time Elizabeth found it essential to drastically assert her authority, and in 1577 an individual named Sherin was not only imprisoned in the Tower for denying her supremacy, but was afterwards drawn on a hurdle to Tyburn, where he was hanged, disembowelled, and quartered. In that same year six other poor creatures were treated in the same manner, after being imprisoned in the fortress, for coining. From 1580 until the close of Elizabeth’s reign the penal laws were enforced with terrible rigour, owing to the invasion of the Jesuit missionary priests led by Parsons and Campion. Cardinal Allen’s seminary priests were ruthlessly hunted down, and when caught, imprisoned, generally tortured, and invariably executed. The Cardinal, who had set up a seminary for priests at Douai, maintained a large and ever increasing staff of young men who were ready to sacrifice their lives in what they believed to be the cause of Heaven. The first to suffer of these was Cuthbert Mayne. Between Elizabeth and the Cardinal the war became fierce and sanguinary. Plot was met by counter-plot, and Cecil showed himself as astute and deep as any Jesuit of them all, the priests of Douai and Allen’s Jesuits faring ill in consequence. Both Campion and Parsons had been at the English Universities, and both for a time succeeded in their mission of bringing over to their religion many from among the higher classes of this country. But Elizabeth’s great minister proved too strong for them, and Campion was arrested and sent to the Tower, whilst Parsons sought safety on the Continent. Campion, with two other priests named Sherin and Brian, was hanged at Tyburn. Many of the imprisoned priests were tortured in the Tower; some were placed in “Little Ease,” where they could neither stand up nor lie down at full length; some were racked, others subjected to the deadly embrace of the “Scavenger’s Daughter,” others being tortured by the “boot,” or the “gauntlets,” and hung up for hours by the wrists. Sir Owen Hopton, the Lieutenant of the Tower at this time, seems to have been a very hard-hearted gaoler, and on one occasion when he had forced some of these wretched priests, with the help of soldiers, into the Chapel of the Tower whilst service was being held, he boasted that he had no one under his charge who would not willingly enter a Protestant Church.

From 1580 onwards, the Tower was filled with State prisoners. In that year the Archbishop of Armagh and the Earls of Kildare and Clanricarde, and other Irish nobles who had taken part in Desmond’s insurrection, were imprisoned in the fortress, and three years later a number of persons concerned in one of the numerous plots against Elizabeth’s life were likewise sent there, among them John Somerville, a Warwickshire gentleman, and his wife, together with her parents, and a priest named Hugh Hall, declared to have designs to murder the Queen. Mrs Somerville, her mother, and the priest were spared; her husband committed suicide in Newgate, where he had been sent to be executed, and her father was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Smithfield. In the following year (1584) Francis Throgmorton, son of Sir John, suffered death for treason like his father, a correspondence between Queen Mary and himself having been discovered. In the month of January 1585, twenty-one priests lay in the Tower, but were afterwards shipped off to France. In this same year Henry Percy, eighth Earl of Northumberland, a zealous Roman Catholic, with Lord Arundel, the son of the fourth Duke of Norfolk, were imprisoned in the Tower. But Northumberland killed himself, locking his prison door, and shooting himself through the heart with a pistol he had concealed about him, being supposed to have committed suicide in order that his property should not come into possession of the Queen—whom he called by a very offensive epithet—as would have been the case had he been attainted of treason. Arundel died in the Beauchamp Tower after a long imprisonment, as has been told in the account of that building. His death was no doubt owing to the severity of his confinement, combined with the austerities he thought it his duty to inflict upon himself; he certainly deserves a place in the roll of those who have died martyrs to their faith.

Another conspiracy against the Queen’s life came to light in this same year, when a man named Parry was arrested on a charge of having received money from the Pope to assassinate Elizabeth, a fellow-conspirator named Neville being taken at the same time, it being alleged that they intended to shoot the Queen whilst she was riding. Neville, who was heir to the exiled Earl of Westmoreland, hearing of that nobleman’s death abroad, turned Queen’s evidence, hoping by this treachery to recover the forfeited Westmoreland estates. His confederate was hanged, and although Neville escaped a similar fate, he remained a prisoner for a considerable time in the Tower.

Axe and halter once more came into play in extinguishing what was known as the Babington Plot in 1586. Elizabeth had never run a greater peril of her life, and it was owing to this plot that Mary Stuart died on the scaffold at Fotheringay on the 8th of February in the following year. Anthony Babington was a youth of good family, holding a place at Court, and, like many other of Elizabeth’s courtiers, belonged to the Roman faith, the Queen being too courageous to forbid Roman Catholics from belonging to her household. The soul of the plot was one Ballard, a priest, who had induced Babington, with some other of his associates, also of the Court, to adventure their lives in order to release Mary Stuart, and to place her upon the throne after having got rid of Elizabeth. Walsingham, with his lynx-eyed prevoyance, discovered the plot, and Ballard with the rest were arrested, tried and condemned. According to Disraeli the elder (in his “Amenities of Literature”) the judge who presided at the trial, turning to Ballard, exclaimed, “Oh, Ballard, Ballard! What hast thou done? A company of brave youths, otherwise adorned with goodly gifts, by thy inducement thou hast brought to their utter destruction and confusion.” Besides Ballard and Babington, thirteen of these young conspirators were executed—to wit, Edward Windsor, brother of Lord Windsor, Thomas Salisbury, Charles Tilney, Chidiock Tichburn, Edward Abington, Robert Gage, John Travers, John Charnocks, John Jones, John Savage, R. Barnwell, Henry Dun, and Jerome Bellarmine. Their execution, accompanied with all its horrible details, lasted for two days, Babington exclaiming as he died, “Parce mihi, Domine Jesu!” On the second day the Queen gave orders that the remaining victims should be despatched quickly without undergoing the attendant horrors of partial hanging, drawing, and quartering.[15]

Mary’s execution followed in the next year, but it was Elizabeth’s secretary, Davison—he had been appointed about this time co-secretary with Walsingham—who had to bear all the odium of her death, Elizabeth accusing him of having despatched the death-warrant without her sanction. She sent him to the Tower and caused him to be fined so heavily that he was completely ruined in consequence. Another scandalously unjust imprisonment in the Tower of a loyal and faithful servant of the Queen, was that of Sir John Perrot, a natural son of Henry VIII. Perrot was a distinguished soldier, and had acted as Lord-Deputy in Ireland, where, by his justice and humanity and clear common-sense, he had done much to restore order and comparative prosperity to that distracted island. Sir John Perrot was cordially hated by the Lord Chancellor, Sir Christopher Hatton, who was particularly noted for his skill in dancing, this hatred having been aroused, it is said, by Perrot remarking that the Lord Chancellor “had come to the Court by his galliard.” This criticism resulted in Perrot’s being arrested, after being summoned from Ireland on a trumped-up charge of treason, and committed to the Tower in 1590. At his trial two years later, nothing could be proved against him except a few idle words that he had uttered concerning the Queen, and which had been repeated to her; nevertheless he was found guilty. When brought back to the Tower, Sir John exclaimed angrily to the Lieutenant, Sir Owen Hopton, “What! will the Queen suffer her brother to be offered up as a sacrifice to the envy of my strutting adversary?” On hearing this, the Queen burst out into one of her finest Tudor rages, and swearing “by her wonted oath,” as Naunton writes, “declared that the jury which had brought in this verdict were all knaves, and that she would not sign the warrant for execution.” So Sir John escaped the headman, but the gallant knight died that September in the Tower, Naunton thus describing the close of his life: “His haughtiness of spirit accompanied him to the last, and still, without any diminution of courage therein, it burst the cords of his magnanimitie.” In his youth Perrot had been distinguished for his good looks and strength of body. “He was,” writes Naunton, “of stature and size far beyond the ordinary man; he seems never to have known what fear was, and distinguished himself by martial exercises.” During a boar hunt in France in 1551, it was related of him that he rescued one of the hunters from the attack of a wild boar, “giving the boar such a blow that it did well-nigh part the head from the shoulders.”

From a memorandum drawn up by Sir Owen Hopton for the use of his successor, Sir Michael Blunt, in the Lieutenancy of the Tower in 1590, we find that the following prisoners were at that time confined in the fortress:—James Fitzgerald, the only son of the Earl of Desmond, who had come from Ireland as a hostage, Florence Macarthy, Sir Thomas Fitzherbert (who died in the Tower in the following year), Sir Thomas Williams, the Bishop of Laughlin, Sir Nicholas White, Sir Brian O’Rourke, “who hath the libertie to walk on the leades over his lodging,” and Sir Francis Darcy. All these prisoners were connected with the war in Ireland, or were suspected of conspiring against the Queen and her government.

The year 1592 is a memorable one in the life of the great Sir Walter Raleigh, for it was then that he began his long acquaintance with the prisons of the Tower, and from this time until his execution a quarter of a century later, Raleigh’s days were mainly passed within the wall