CHAPTER XVII.

A WATER EXCURSION.

THE next Saturday Whistler came home from school in great haste, at noon, and informed his mother that several of his young associates were going to get a sailboat and take a cruise in the harbor, immediately after dinner, and had invited him to go with them. Each boy was to pay a small sum for the use of the boat, the amount of which assessment would depend upon the number in the party. Whistler was quite anxious to go with them, and he knew Clinton would be, also, although he had not been able to find him since school was dismissed. The day was calm and pleasant, the boys who were going were of good character, several of them understood managing a boat, and they could not help having a good time. Such was Whistler’s story.

But his mother was not at all pleased with the project. She did not consider it safe for a party of such boys to venture upon the water, without a man capable of managing the boat. Whistler argued and pleaded, but could not change her mind. She finally told him that she should not give her consent to his going, and wished he would abandon the idea; but added that, if he was very anxious to go, he might ask his father’s permission, and if it was granted she should say nothing more about it.

As Mr. Davenport generally dined down town when business was pressing, Whistler started at once for his office. He found his father deeply engaged with several gentlemen, and some time elapsed before he could get even a look from him. After a while the busy lawyer stepped aside, and, telling his son to “speak quick,” listened to his request. He asked a question or two about the boys who were going, and, taking a handful of change from his pocket, gave Whistler enough to pay for himself and Clinton, and told him they might go with the party.

Whistler hastened home, and informed his mother of his success; but she kept her promise, and said nothing about the matter, although he tried hard to draw from her some modification of her judgment. Soon one of the boys who was getting up the party called to see whether Whistler was going. For a moment he was in doubt what reply to make. He could not consult Clinton, who had not yet returned. He wanted to go very much, but he did not wish to set at defiance the known wishes of his mother. He soon, however, made up his mind what to do. After a short but severe struggle in his mind, he told the boy that he should not go. When Clinton came in, and was informed of the affair, he appeared to be satisfied with Whistler’s decision, though it was no less a disappointment to him than to his cousin.

“Well, boys, you have got back in good season from your excursion,” said Mr. Davenport, when he came home from his business that afternoon.

“We didn’t go,” replied Whistler.

“Didn’t go!—how happened that?” inquired his father.

“Mother didn’t want us to go, and so I thought we had better give it up,” replied Whistler.

“That was a good reason,—a very good reason,” said his father. “On the whole, I think your mother was about right. It isn’t safe for a lot of boys to go on the water alone; and I was sorry, five minutes afterwards, that I consented to your going.”

There the matter dropped; but the regard Whistler had manifested for his mother’s wishes was not forgotten by either of his parents. It was talked over when they were alone, and it was determined to reward him in some way for his self-denying decision. The next Monday his mother had the pleasure of informing him that the whole family were going to sail in the harbor the following Wednesday, which was his birthday. Mr. Davenport had chartered a fine yacht[3] for the occasion. Whistler had liberty to invite the Preston children, and also Marcus, to go with them; and several other invitations were likewise to be extended.

Whistler lost no time in spreading the news of this arrangement among those who were interested. He learned that Marcus and Oscar had intended to start for Vermont on the day of the proposed excursion; but they were easily persuaded to postpone their journey for one day, for the sake of joining the party. Ella and her brothers, Ralph and George, only awaited their father’s consent to give the invitation a cordial acceptance. Indeed, so impatient were they, that Ralph proceeded at once to his father’s store, and obtained the desired permission. Clinton and Whistler went with him, and the first-named had the gratification of meeting his chance acquaintance, Henry Hoyt, who had that morning entered upon the service of Mr. Preston. Henry was not a little surprised to find that there was so close a connection between his courtesy to a fellow stranger and the success of his application for a situation.

Wednesday came, and Whistler was fourteen years old. The accustomed birthday present from his parents, which had never failed him within his recollection, was found upon his table when he awoke. It was a plain but highly-polished rosewood box, filled with implements and materials for drawing. Everything that a young artist could desire in the pursuit of his favorite study was here to be found, neatly secured in its own place. Whistler was delighted with the gift, and assured his parents that they could not possibly have selected a present that would have pleased him better.

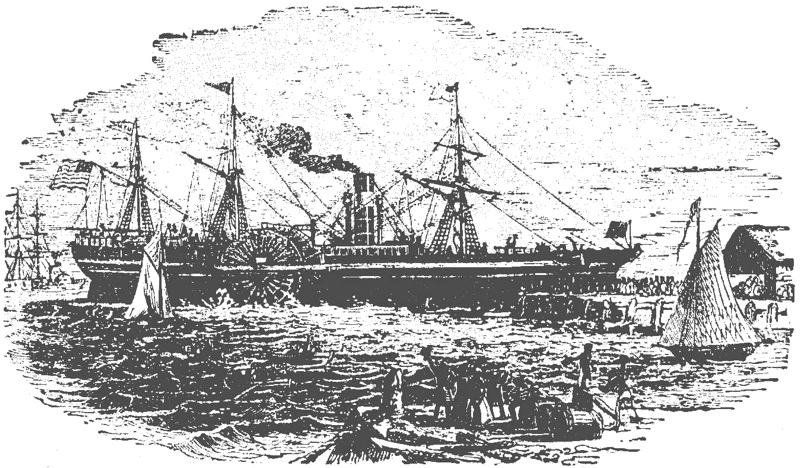

After breakfast, active preparations were made for the excursion; and promptly, at the hour appointed, all of the company invited were assembled upon the wharf where the yacht lay. The “Echo,” as she was called, was rigged as a sloop,—that is, she had but one mast, and a bowsprit. She was of about twenty-five tons burden, and looked quite small by the side of the huge ships of ten or twelve hundred tons which surrounded and overshadowed her. While these leviathans towered high above the wharves, the modest Echo sat so low in the water that the party had to go down a ladder to reach her deck. She was a neat, trim, and graceful craft, however, and everything about her was scrupulously clean. A blue pennant was flying from her masthead.

The party seated themselves in the stern of the yacht, where they found very good accommodations, while the skipper and his two men—who constituted the whole crew—took their positions forward. Having cast off their lines, they hoisted the jib, and began to push out from the wharf. Both the wind and tide were contrary, and it required some nautical skill to get out into the stream. Once clear from the wharf, the first thing they did was to run into a small row-boat, and the next was to thump against the side of a large steamboat which lay at the opposite wharf. No harm was done, however; and, after a few unintelligible orders from the skipper,—who had now taken his post at the helm,—they swung clear of every obstacle, the mainsail was hoisted, and they were under way.

The wind being in an easterly direction, the yacht was obliged to “beat out,” as it is called; that is, instead of taking a direct course for the outer harbor, she had to sail in zigzag lines, approaching very gradually towards the point to which she was bound. The first “tack,” as the sailors term the course of a ship when beating against the wind, took the Echo close to the shore of East Boston. A large steamship, just arrived from Europe, was entering her berth; and, at the request of several of the party, the captain of the yacht sailed up to within a few yards of her, giving all on board a fine opportunity to inspect the huge and stately leviathan. What an impression of strength and beauty, of gigantic power and indescribable grace, did they derive, as they gazed up from their frail and tiny craft upon the towering walls of this ocean monster! A crowd was assembled upon the wharf, awaiting the landing of the passengers; and several small boats were hovering around, drawn thither, probably, like the Echo, by curiosity. Altogether, it was a very lively and interesting scene. After sailing slowly by the steamship, the Echo was put upon a new tack, heading towards the opposite side of the stream. In taking these tacks from one side to the other, considerable skill was required to steer clear of the numerous vessels of all sorts that were lying in the course of the yacht.

“Beautiful!” “charming!” “splendid!” were exclamations that frequently arose above the general buzz of conversation, in the stern, as the Echo glided smoothly over the waters. Nor were these extravagant terms; for a sail down Boston harbor, on such a day, and in such a craft, is one of the pleasantest excursions that can be imagined. But, while some of the party were enjoying the beautiful views that presented themselves, others, and especially the boys, were engaged in watching their boat, and in examining its various appointments.

“What queer seats these are! What is the object of making them in that shape?” inquired Clinton, as he examined a stool that was shaped somewhat like an hour-glass, and was made of tin, and painted, with the name of the yacht inscribed upon it.

“That is a life-preserver, as well as a stool,” replied Whistler. “If any one should fall overboard, they would throw him one of these stools, and that would keep his head above water till they could get him out.”

“Now, look out for your heads, ladies, if you please!” said the captain, as he was about to swing the boom around to the other side of the boat, for the purpose of changing the tack.

“No matter about the gentlemen’s heads!” said Whistler; and, suiting the action to the word, he sat upright until the boom came upon him, and then, dodging it a little too late, it took his hat from his head, and, but for a quick movement on his part, would have sent it whirling into the water.

“If you had sat still a moment longer, Willie, we might have had an opportunity to experiment with one of these life-preservers,” said Marcus.

“I know it,” replied Whistler; “and I’m not going to stay here and be knocked round in this way! Come, boys, let’s go down into the cabin.”

Several of the party accepted Whistler’s invitation. The cabin occupied the middle part of the boat. Of course it was a rather small apartment; but, for all that, there was a good deal in it. Every available inch of room was fully improved. It was only about five feet high,—not high enough to allow Marcus and Oscar to stand up straight. A permanent table ran nearly the whole length, with leaves that dropped down when not in use. There was a raised edge around the table, to keep the dishes from sliding off when the sea is rough. The mast came up through the table, but was handsomely paneled, and, but for its decided slant, might have passed for a pillar. A castor and a basket full of tumblers were hanging over the table, and benches were placed on each side of it.

The cabin was also fitted up with berths, very much like the one which Whistler occupied on board the steamboat, on his journey to Brookdale. There were four of them on each side, and they were furnished with neat white bedding. Under each berth there was a locker, for stowing away clothing, &c. The cabin was lighted by the doorway, and by a skylight, which was raised a little above the level of the deck.

Forward of the cabin, and connected with it by a door, was the cook-room. It contained a cooking-stove, with a bright brass railing around the top, to keep things in their places. The funnel went up through the deck. A man was kindling a fire, and as the room seemed too small to hold two at once, the boys did not go in.

Returning to the deck, the boys found that they were off Fort Independence (Castle Island), distant a little more than two miles from the city. The view was now very fine. The numerous islands of the harbor began to appear, and glimpses of the ocean were obtained between their green and sunny slopes. Several vessels, availing themselves of a favorable wind, were entering the port in gallant style. Among them was a noble ship, returning from a distant voyage. But few of her sails were spread, yet she dashed through the waters with such grace and speed that the boys could not refrain from giving her three cheers as she passed their boat. The compliment was promptly returned by the sailors.

The next object of interest that the Echo passed was the Long Island Light, distant about five miles from the city. The air was now growing uncomfortably cool, and the captain brought up from the cabin a quantity of shawls, hoods, old hats, &c., which he said he kept expressly for company. They were gratefully accepted; and the sudden outward transformation which the party underwent, furnished no little food for merriment.

At noon, the captain invited the company to take something to eat. On descending to the cabin, they found the table spread with a variety of eatables. There were boiled ham, and tongue, and eggs; pies, crackers, and bread; sardines, olives, and pickles; hot coffee and tea, and genuine Cochituate, fresh, not from the pipes, but from an ice-tank. There is nothing like snuffing the sea air to give one an appetite; and the plain, substantial fare disappeared very rapidly from the table. Before the meal was concluded, however, Ella and one or two others left the table rather suddenly. Oscar, who was more of a sailor than any of the rest, rallied his sister on her prompt acknowledgment of the claims of Neptune; but she protested that she did not feel at all sick. Very possibly she would, though, had she remained below a little longer. The fresh air revived her, and the slight nausea she began to experience in the cabin soon passed away.

The Echo was now seven miles out, but had, in reality, sailed twenty-five miles in making that distance. The broad ocean was in full view, studded with sails, and the sea was much rougher than it was before dinner. A large steamship was soon discovered, threading its way out from among the islands. It was watched with much interest by all, and as it passed near them they had a good view of it. It proved to be a screw steamer; that is, instead of paddle-wheels on the sides, the power was applied to a propeller under the ship’s keel. She presented a noble and substantial appearance as she sailed down the harbor, impelled by an invisible power, and seemed strong enough to withstand any shock that she might encounter on the ocean. A clipper ship, outward bound, also passed near them, having most of her canvas spread, and was an object of scarcely less interest than the steamship.

The yacht was now approaching George’s Island, where the party had decided to land. This island, which is the key to the outer harbor, commanding the open sea, belongs to the United States, and contains one of the most extensive and costly fortifications in the country. The fortress, however, is in an unfinished state. As they drew near to the island, they found that it was surrounded by a sea wall, composed of immense blocks of granite. This is necessary, to prevent the washing away of the island in the furious storms which sweep over the coast. The winds and waves have made sad inroads upon the islands in the harbor, even within the memory of many now living. It is said that the breakers now roll where large herds of cattle were pastured seventy-five years ago.

Having landed at the wharf, the party walked up towards the fort, which is named after General Warren. Immense walls of granite, of the purest quality and smoothest finish, towered above them. On the top of the walls were banks of earth, neatly sodded. The road led them to a substantial stone gateway, which was open, and they accordingly entered it. They now found themselves in a narrow passageway, with high walls on either side. There were many long and narrow openings in the walls, through which muskets could be fired, should an enemy succeed in landing, and try to take the fort. An invading force, hemmed in by the walls, would receive a dreadful raking from these loopholes before they could get inside of the fortress.

On reaching the interior of the fortification they found themselves in a large area. The captain of the yacht, who acted as their guide, informed them that twelve acres were enclosed, and three more were occupied by the walls. There were several workshops and a large dwelling-house within the enclosure. As they were examining the fine specimens of masonry which the walls presented, a gentleman wearing the uniform of an army officer came up to them, and politely offered to show them over the fortress. His offer was gratefully accepted.

“We will first ascend the parapets, if you please,” said the officer, leading the way towards a long flight of stone steps.

“Work seems to be suspended here,” remarked Mr. Davenport, as they passed several ox-carts that were covered with rust.

“Yes, sir,” replied the officer; “the appropriation is exhausted, and nothing has been done here for several months.”

“This place will have cost Uncle Sam some money, when it is finished,” continued Mr. Davenport.

“Something over a million of dollars, probably,” replied the officer.

“Well, perhaps it will be worth that money, in case of war,” said Mr. Davenport; “but it strikes me that fighting is a pretty costly business.”

“O, what a splendid view!” was the general exclamation, as the party reached the top of the parapet.

“You perceive that the whole harbor is completely commanded by the fort,” continued the officer. “Here, within a pistol shot, is the main channel, through which all large vessels must pass as they enter or leave the harbor. If an enemy’s ship were to try to pass here, after the fort is mounted, we could bring from a hundred to a hundred and fifty guns to bear upon her, at the same time, at any point.”

They continued their walk upon the top of the parapet for some minutes, enjoying the fine view to be had on every side. It is here that the heaviest guns are designed to be placed, in the open air. Large square stones are set for the guns to rest upon, and semi-circular ones for the gun carriages to traverse. There is also a wall, behind which the men can hide.

On descending from the parapet, the officer unlocked a door, and, through a rather gloomy passage, led them into the interior of the fortress. Here they wandered for a quarter of an hour through a labyrinth of massive masonry, gazing with wonder at the solid walls, the arched stone roof, and the long series of rooms connected by doors. They found but one gun mounted, but that served to illustrate the principle on which the cannon are intended to work. The port-holes are so shaped that the guns are allowed a wide range, and yet there is little room for shot to enter from without. They have an inner and an outer flare, being narrowest in the centre of the wall. That part of the carriage farthest from the muzzle has a sideway motion, so that the gun may be readily pointed in any direction required. The fort will mount about three hundred guns.

Besides the gun-rooms there are a large number of other apartments, to which the party were introduced. Some of them are intended for ante-rooms, into which the soldiers may retire. They have fireplaces, and will doubtless wear an air of comfort and cheerfulness when finished and furnished. Other apartments, designed as parlors for the officers, are still more expensively finished. There are also kitchens, sleeping-rooms, magazines, cells for prisoners, &c.

“This must be one of the finest fortresses in the country,” said Mr. Davenport, as they came out once more into the open air.

“Yes, sir, it is,” replied the officer. “It is impregnable from sea; but, if it could be attacked by land, it might be blown to pieces, after a while. No masonry is solid enough to be proof against efficient land batteries,—that was proved at Sebastopol.”

“Well,” said Mr. Davenport, “the worst wish I have for Uncle Sam is that he may never have occasion to use this immense fortress.”

“I heartily join you in that wish, in spite of my profession,” replied the officer; and he then politely took leave of them.

Warmly thanking their guide for his attentions, the party hastened to their boat, and were soon on their way back. The wind had died away, and their progress homeward was not very rapid. The skipper evidently felt somewhat concerned for the credit of his craft. He declared that she was a swift sailer; but nothing, he said, could sail without wind, or in the face of a stiff breeze. His equanimity seemed to be still more seriously disturbed when a large schooner, with a great spread of canvas, came up behind him, and began to gain upon the Echo. He kept a sharp eye upon the intruder, as he evidently regarded her; and when she passed the Echo to the windward, instead of the leeward, he could no longer restrain his disgust, but remarked to Mr. Davenport, with some warmth:

“A fellow that’ll do that is no gentleman!”

A puzzled look from several of the ladies, who did not understand the nature of the offence, recalled him to a sense of his dignity, and he was soon as gallant and as good-natured as usual. In justice to him, it should be remarked that the schooner, by going to the windward, had taken the wind out of his sails, which is not considered a very courteous act among sailors.

The party reached the wharf in safety, and all declared that they never spent a pleasanter day than in their trip down the harbor.