CHAPTER XVIII.

LAST DAY OF THE VISIT.

CLINTON remained in Boston about six weeks, or until the middle of October. During that time he made himself pretty well acquainted with the city, and visited all the objects of interest in and around it. At length the last day of his sight-seeing was over, his valise was packed, and he sat down with his uncle’s family for the last time. It was a cool evening, and a fire in the grate sent out a cheerful warmth. His uncle sat near the table, reading the evening newspaper. His aunt was busy with her needle. Whistler was conning his next morning’s lesson, and Ettie was showing to kitty the pictures in one of her books, while Bouncer was asleep upon the mat. Clinton alone sat idle; but he was not wholly unoccupied. His thoughts were busy, and a feeling of sadness was stealing over him as the hour of his departure drew near.

After a while Mr. Davenport laid his paper aside, and Whistler took it up. He glanced over one of its columns with some care, and then said:

“No news from the Susan yet; you will have to go home without Jerry, Clinton.”

The Susan was the brig in which Jerry Preston sailed. She was now expected at Boston; and the boys had looked daily in the newspapers for the intelligence of her arrival. Clinton had some hope that Jerry would get back in season to return with him to Brookdale; but in this he was disappointed.

“Well, Whistler, what have you learned to-day?” inquired Mr. Davenport,—a question which he frequently addressed to his son, in the evening.

“Let me see,” replied Whistler, slowly. “O, I’ve learned which are the three hardest words to pronounce in the English language.”

“Ah! what are they?” inquired his father.

“They are, ‘I was mistaken,’” replied Whistler.

“What is there so very hard to pronounce about them?” inquired his father, with affected simplicity.

“It isn’t the words that are hard,—it’s the sentiment,” replied Whistler. “Our teacher told us that some great man once said those were the three hardest words to pronounce in the English language. He told us, besides, of a great general who was defeated in battle, and who sat down and wrote to the senate: ‘I have just lost a great battle, and it was entirely my own fault.’ He said that confession displayed more greatness than a victory.”

“That is very true,” added Mr. Davenport. “But have you learned to pronounce the words yourself? If you have, you have learned something worth knowing.”

“I don’t know,” replied Whistler, with some hesitation.

“The item of knowledge you have picked up to-day,” continued his father, “will not be of much benefit to you, unless you make a practical use of it. Your teacher, I suppose, wished to teach you the duty of confessing your errors. That is one of the hardest things a man ever has to do. It takes a brave man to confess that he has done wrong, or has embraced wrong opinions.”

“I’ve learned another thing to-day,” continued Whistler; “I’ve learned how much meanness there is in the world.”

“Ah, you have made an important acquisition!” said his father. “I’ve lived in the world forty years, and I haven’t begun to find out all its meanness yet.”

“Well, if I haven’t found it all out, I’ve found enough,” resumed Whistler. “This was the way it happened. Two or three boys of our class came to me, this morning, and wanted me to sign a petition asking the teacher to give us shorter lessons. About a dozen boys had signed it, but they wanted me to put my name before theirs, at the head of the petition, because I was one of the oldest boys. As soon as I found what it was for, I told them I didn’t think our lessons were too long, and I shouldn’t sign it. Then they all set upon me, and coaxed and flattered as hard as they could. They said they were so sure that I would sign it that they had left a place for my name, and that I should have more influence with the master than they, &c., &c. And when they found that that wouldn’t work, then they tried to bully me into it. Nat Clapp said I needn’t pretend to be a better scholar than the rest of them, for I had as hard work to get my lessons as any body did. Jo Clark said I wouldn’t sign it because they didn’t consult me about it before they got it up. Bill Morehead said I didn’t dare to sign it. I told him I dared to refuse to sign it, and I thought that was more than some of them could say. But I can’t tell you half what they said. I got real provoked at last. I should like to know if I hadn’t as good a right not to sign that petition as any of them had to sign it? What business had they to say my motives were bad, because I didn’t please to do just as they wanted me to?”

“How much boys are like men!” quietly remarked his father.

“But you didn’t sign the petition after all, did you?” inquired Clinton.

“No, that I didn’t,” replied Whistler; “and I was glad enough of it, too, this afternoon. They couldn’t get but about a third of the class to sign it, and they left it on the teacher’s desk this noon. He didn’t say anything about it till just as school was about to be dismissed at night. Then he told the scholars that he had received a petition for shorter lessons from a portion of the first class. He said the request was not only unreasonable, but the petition was disrespectful in tone, and he considered it insulting. He said most of the boys who had signed it were the idlest fellows in the class, and, he supposed, they would like it better if he would give them no lessons at all. But, he said, there were one or two names on the petition that he was surprised to see there. He talked pretty hard to them, I can tell you. He said every boy that had put his name to it deserved to be called out and punished; but he concluded to let them off, this time, with merely reading their names aloud to the school. So he read off the list; and if some of the fellows didn’t feel cheap enough, then I’m no judge, that’s all!”

“Did any body sign it that I know, except Nat?” inquired Clinton.

“Yes, there was one other boy that you know; but I shan’t tell you who he is,” replied Whistler.

Clinton did not feel much curiosity in the matter, and did not press the inquiry. The boy referred to was Ralph Preston, who had thoughtlessly yielded to the solicitations of his comrades, and affixed his name to the petition, without noticing that it was not couched in respectful terms. He felt the public reprimand of the act very keenly; and Whistler, out of friendship for him, kindly abstained from giving any further notoriety to his error.

“Well, Clinton,” said Mr. Davenport, after a short pause, “you’ve explored our city pretty thoroughly,—now let us have your judgment upon it. What do you think of it, on the whole?”

“O, I like it very well!” replied Clinton.

“That is rather faint praise,” observed his uncle.

“I like some things very much,” continued Clinton, “and others I don’t like so well.”

“On the whole, don’t you feel quite willing to go back to the country?” inquired his aunt.

“I don’t know but I do,” replied Clinton, with some hesitation.

“I see you haven’t wholly given up the idea of being a merchant, yet,” remarked his uncle.

“O no, sir, I wasn’t thinking of that!” replied Clinton. “But I should like to enjoy some of the opportunities that boys have here,—good schools, and plenty of books, and lectures, and everything else.”

“These privileges or opportunities are very valuable, I know,” added Mr. Davenport; “but, after all, don’t you know that the making of a man is not in opportunities, but in himself? If you determine to be a man, the lack of opportunities will not keep you back. You will work and struggle till you have overcome every obstacle. On the other hand, if you haven’t this strong will within, all the opportunities in the world won’t make a man of you. Indeed, there is such a thing as having too much assistance. If you set out a tree, and keep forever handling it, and scratching about it, and trying to help it grow, it won’t come to much. It needs a little wholesome neglect to teach it to take care of itself. So, if a man wants to produce a strong, rugged character, he mustn’t go into a hothouse to do it. Such a thing won’t grow there. So far as I can judge, Clinton, you are doing very well with your present opportunities. Make the most of them, and I think you will get along as well as most boys in the city, to say the least.”

“But I don’t have much time to study,” added Clinton.

“Many men have stored their minds with valuable information,” continued his uncle, “in odd moments snatched from their labors. Two of the most learned men, in many respects, that I ever met with, did this. One of them is Elihu Burritt, the ‘Learned Blacksmith,’ who acquired more languages at the anvil than I can remember the names of. The other is Charles C. Frost, of Brattleboro’, Vermont, who deserves to be called the ‘Learned Shoemaker.’ I must read you a short account of Mr. Frost, to show you what can be done in one hour a day.”

So saying, Mr. Davenport took down a volume from the bookcase, and read as follows:

“At fourteen years of age, Mr. Frost left school, and commenced learning the trade of a shoemaker. He worked as an apprentice in his father’s shop seven years, when he shortly after became interested in the business of making and vending shoes, in a neat and tasteful shoe store, on his own account. He early evinced a love of mathematical science, and has displayed talents of no ordinary character in its pursuit. He says, in a letter which I have received from him: ‘I early imbibed a love of study. I recollect my first acquisitions were in Arithmetic, and that the results gave me the highest pleasure. When I excelled other boys in the school, my progress was attributed by them to some peculiar mathematical talent. But it was not so. I boast of no genius. I attribute my success uniformly to more study than others gave their lessons or work, and, perhaps, to a greater love of study.’ Mr. Frost has found time, not only to become master of all existing forms of algebraic numbers, but is also familiarly and thoroughly acquainted with Geometry, Trigonometry and Astronomy. He is at home in the Modern Calculus and in the Principia of Newton, where few of our learned professors venture, or feel at ease. Indeed, in mathematical science he has made so great attainments that it is doubtful whether there can be found ten mathematicians in the United States who are capable, in case of his own embarrassment, of lending him any relief. Remember that we are speaking of a self-taught scholar, and he no genius. Let me tell you how it was done. He says: ‘When I went to my trade, at fourteen years of age, I formed a resolution, which I have kept till now,—extraordinary preventives only excepted,—that I would faithfully devote one hour each day to study, in some useful branch of knowledge.’ Here is the secret of his success. He is now forty-five years of age, and is a married man, the father of three children; yet this one-hour rule accompanies him to this day. ‘The first book which fell into my hands,’ he says, ‘was Hutton’s Mathematics, an English work of great celebrity, a complete mathematical course, which I then commenced,—namely, at fourteen. I finished it at nineteen, without an instructor. I then took up those studies to which I could apply my knowledge of Mathematics, as Mechanics and Mathematical Astronomy. I think I can say that I possess, and have successfully studied, all the most approved English and American works on these subjects.’ After this, he commenced Natural Philosophy and Physical Astronomy. Then Chemistry, Geology, and Mineralogy, collecting and arranging a cabinet. ‘Next Natural History,’ he says, ‘engaged my attention, which I followed up with close observations, gleaning my information from a great many sources. The works that treat of them at large are rare and expensive. But I have a considerable knowledge of Geology, Ornithology, Entomology, and Conchology.’ Not only this; he has added to his stores of knowledge the whole science of Botany, one of the most extensive now pursued, and has made himself completely master of it. He has made actual extensive surveys, in his own state, of the trees, shrubs, herbs, ferns, mosses, lichens, and fungi. Mr. Frost thinks that he may possess the third best collection of ferns in the United States. He has also turned his attention to Meteorology, and devotes much of his time, as do also Olmstead, Maury, Redfield, Smith, Loomis, Mitchell, and many others, to acquire a knowledge of the law of storms, and the movements of the erratic and extraordinary bodies in the air and heavens. He has also been driven to the study of Latin, and reads it with great freedom. He has read and owns most of the gifted poets, and is, to a considerable extent, familiar with History; while his miscellaneous reading has been very extensive. He says of his books: ‘I have a library, which I divide into three departments,—scientific, religious, literary,—comprising the standard works published in this country, containing five or six hundred volumes. I have purchased these books, from time to time, with money saved for the purpose by some small self-denials.’

“Here, then, we have an account—I assure you it is wholly reliable—of one, a plain man of forty-five, who has made the compass, so to speak, of the hill of science, studying his HOUR a day, when the day’s labor was done, for more than thirty consecutive years. He began this one-hour system when he was fourteen years old. Behold the result! Here is a man with the cares, business, and responsibilities of life on his hands, yet a devoted, faithful, successful student; a man who is a profound scholar, and yet a plain-spoken, humble, pious, laboring man, residing still in his native village, far inland, supporting himself by his trade and daily labor, while he is worthy of a position as a teacher in one of the best institutions of learning in the land.”[4]

“There,” resumed Mr. Davenport, closing the book, “you see what a man can do in only one hour a day, diligently improved. Don’t you think you might manage to devote that amount of time to study, Clinton?”

“Yes, sir, I suppose I could,” replied Clinton.

“Do you suppose every body could learn as much as Mr. Frost knows, if they should try as hard?” inquired Whistler.

“I suppose any man of fair natural powers, who should study as earnestly and perseveringly as he did, would be about as successful,” replied Mr. Davenport. “But, after all, we must aim at something higher than success. We cannot all be great, or learned, or rich, or eloquent; but we can all be what is better,—we can be good men and women. Indeed, without a good character, all other gifts and acquirements only make a man the more dangerous. And character, you know, is formed by little and little. It is the result of a great multitude of little thoughts, and acts, and emotions, all spun together into a complete fabric. Did you ever go into a ropewalk, Clinton?”

“Yes, sir; Willie and I went through the ropewalk in the Navy Yard,” replied Clinton.

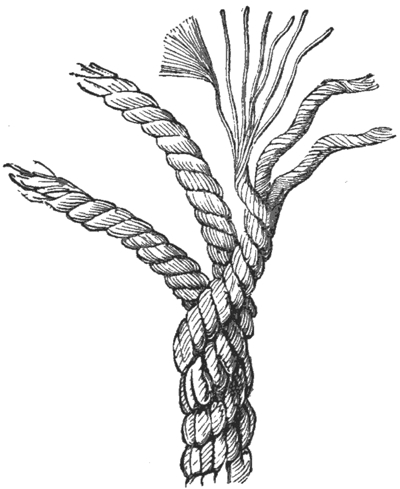

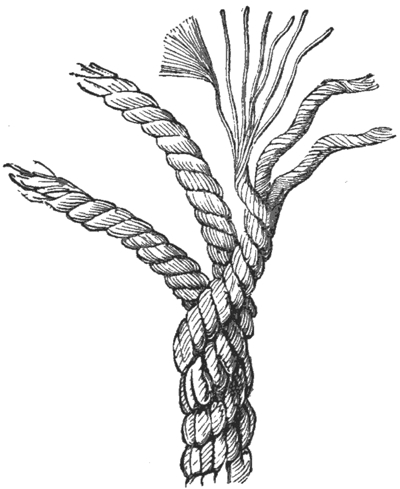

“Well,” resumed his uncle, “the process of making character is something like making a cable. First, there are the little fine fibres of hemp; a great mass of these, twisted together, become yarn; several yarns make a strand; three strands make a rope; and three ropes make a small cable. A fibre of hemp is a very small and weak affair; but twist enough of them together, and they will hold the largest ship in the gale. So the little trifling acts and habits of the child seem very insignificant; but, by-and-by, when they are spun into character, they will become as strong as cables. Look out now, boys, and see that the little fibres, and yarns, and strands, are all right; and in due time the great ropes and cables will appear, and will hold the anchor fast, when you are overtaken by the storms of life.

“There, I have spun you out quite a speech; and a pretty eloquent one, too!—eh, Whistler? Well, the fact is, I’ve been addressing a jury this afternoon, and I haven’t had time to shake the kinks of oratory out of my tongue, yet. Ettie, darling, did my fine speech put you to sleep? Never mind,—don’t disturb her. We shall have to follow her example before long, if we mean to see Clinton off in the morning.”

The family retired at an early hour; and the next morning Clinton bade them good-by, and set out for Brookdale.

THE END.