X

LIFE OF SLAVES ON THE ISLANDS

They stand in the Gulf of Guinea—those two islands of San Thomé and Principe where the slaves die—about one hundred and fifty miles from the nearest coast at the Gaboon River in French Congo. San Thomé lies just above the equator, Principe some eighty miles north and a little east of San Thomé, and a hundred and twenty miles southwest of Fernando Po. San Thomé is about eight times as large as Principe, and the population, which may now be reckoned considerably over forty thousand, is also about eight times as large. It is difficult to say what proportion of these populations are slaves. The official returns of 1900 put the population of San Thomé at 37,776, including 19,211 serviçaes, or slaves, with an import of 4572 serviçaes in 1901. And the population of Principe was given as 4327, including 3175 serviçaes. But the prosperity of the islands is increasing with such rapidity that these numbers have now been probably far surpassed.[14]

It is cocoa that has created the prosperity. In old days the islands were famous for their coffee, and it is still perhaps the best in Africa. But the trade in coffee sank to less than a half in the ten years, 1891 to 1901, while in that time the cocoa trade increased fourfold—from 3597 tons to 14,914—and since 1901 the increase has been still more rapid. The islands possess exactly the kind of climate that kills men and makes the cocoa-tree flourish. It is, as I have described, a hot-house climate—burning heat and torrents of rain in the wet season, from October to April; stifling heat and clouds of dripping mist in the season that is called dry. In such an air and upon the fine volcanic soil the cocoa-plant thrives wherever it is set, and continues to produce all the year round. Nearly one-third of the islands is now under cultivation, and the wild forest is constantly being cleared away. In consequence, the value of land has gone up beyond the dreams of a land-grabber’s avarice. Little plots that could be had for the asking ten years ago now fetch their hundreds. There is a story, perhaps mythical, that one of the greatest owners—once a clerk or carrier in San Thomé—has lately refused £2,000,000 for his plantations there. In 1901 the export trade from San Thomé alone was valued at £764,830, having more than doubled in five years, and by this time it is certainly over £1,000,000. There are probably about two hundred and thirty plantations or “roças” on San Thomé now, some employing as many as one thousand slaves. And on Principe there are over fifty roças, with from three hundred to five hundred slaves working upon the largest. All these evidences of increasing prosperity must be very satisfactory to the private proprietors and to the shareholders in the companies which own a large proportion of the land. For the most part they live in Lisbon, enjoying themselves upon the product of the cocoa-tree and the lives of men and women.

One early morning at San Thomé I went out to visit a plantation which is rightly regarded as a kind of model—a show-place for the intelligent foreigner or for the Portuguese shareholder who feels qualms as he banks his dividends. There were four hundred slaves on the estate, not counting children, and I was shown their neat brick huts in rows, quite recently finished. I saw them clearing the forest for further plantation, clearing the ground under the cocoa-trees, gathering the great yellow pods, sorting the brown kernels, which already smelled like a chocolate-box, heaping them up to ferment, raking them out in vast pans to dry, working in the carpenters’ sheds, superintending the new machines, and gathering in groups for the mid-day meal. I was shown the turbine engine, the electric light, the beautiful wood-work in the manager’s house, the clean and roomy hospital with its copious supply of drugs and anatomical curiosities in bottles, the isolated house for infectious cases. To an outward seeming, the Decree of 1903 for the regulation of the slave labor had been carried out in every possible respect. All looked as perfect and legal as an English industrial school. Then we sat down to an exquisite Parisian déjeuner under the bower of a drooping tree, and while I was meditating on the hardships of African travel, a saying of another of the guests kept coming back to my mind: “The Portuguese are certainly doing a marvellous work for Angola and these islands. Call it slavery if you like. Names and systems don’t matter. The sum of human happiness is being infinitely increased.”

The doctor had come up to pay his official visit to the plantation that day. “The death-rate on this roça,” he remarked, casually, during the meal, “is twelve or fourteen per cent. a year among the serviçaes.” “And what is the chief cause?” I asked. “Anæmia,” he said. “That is a vague sort of thing,” I answered; “what brings on anæmia?” “Unhappiness [tristeza],” he said, frankly.

He went on to explain that if they could keep a slave alive for three or four years from the date of landing, he generally lived some time longer, but it was very difficult to induce them to live through the misery and homesickness of the first few years.

This cause, however, does not account for the high mortality among the children. On one of the largest and best-managed plantations of San Thomé the superintendent admits a children’s death-rate of twenty-five per cent., or one-quarter of all the children, every year. Our latest consular reports do not give a complete return of the death-rate for San Thomé, but on Principe 867 slaves died during 1901 (491 males and 376 females), which gives a total death-rate of 20.67 per cent. per annum. In other words, you may calculate that among the slaves on Principe one in every five will be dead by the end of the year.[15]

No wonder that the price of slaves is high, and that it is almost impossible for the supply from Angola to keep pace with the demand, though the government calls on its Agents to drive the trade as hard as they can, and the Agents do their very utmost to encourage the natives to raid, kidnap, accuse of witchcraft, press for debts, soak in rum, and sell. A manager in Principe, who employs one hundred and fifty slaves on his roça, told me that it is impossible for him fully to develop the land without two hundred more, but he simply cannot afford the £6000 needed for the purchase of that number.

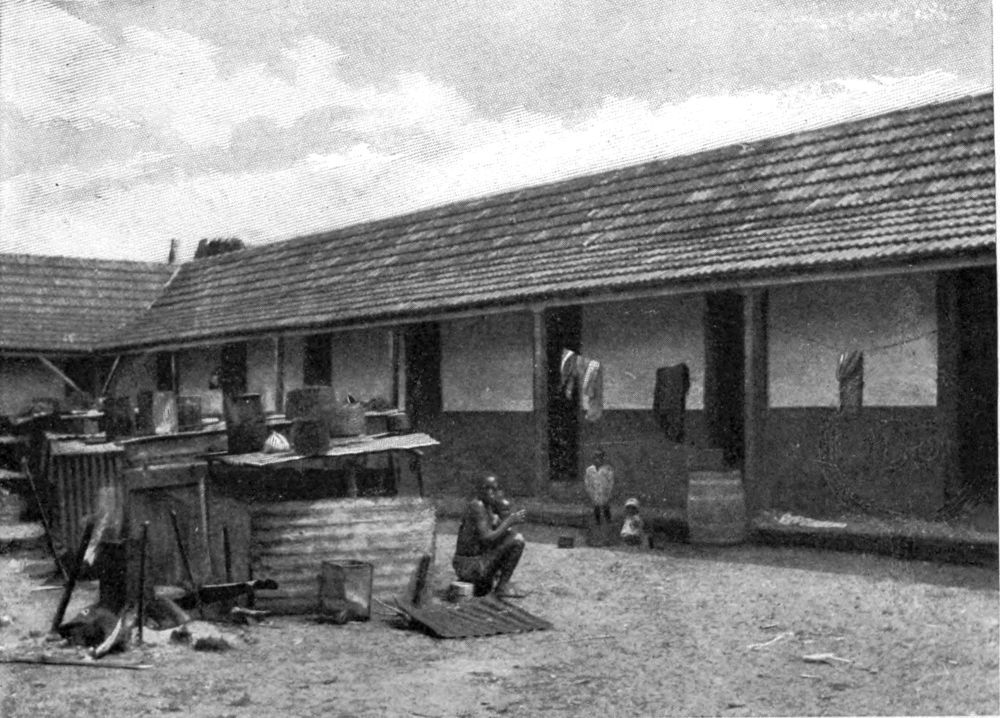

The common saying that if you have seen one plantation you have seen all is not exactly true. I found the plantations differed a good deal according to the wealth of the proprietor and the superintendent’s disposition. Still there is a general similarity in external things from which one can easily build up a type. Let us take, for instance, a roça which I visited one Sunday after driving some six or seven miles into the interior from the port of San Thomé. The road led through groves of the cocoa-tree, the gigantic “cotton-tree,” breadfruit, palms, and many hard and useful woods which I did not know. For a great part of the distance the wild and untouched forest stood thick on both sides, and as we climbed into the mountains we looked down into unpenetrated glades, where parrots, monkeys, and civet-cats are the chief inhabitants. The sides of the road were thickly covered with moss and fern, and the high rocks and tree-tops were from time to time concealed by the soaking white mist which the people for some strange reason call “flying-fish milk.” High up in the hills we came to a filthy village, where a few slaves were drearily lying about, full of the deadly rum that hardly even cheers. A few hundred yards farther up was the roça which owns the village and runs the rum-shop there for the benefit of the slaves and its own pocket. The buildings are arranged in a great quadrangle, with high walls all round and big gates that are locked at night. On one side stands the planter’s house, and attached to it are the dwellings of the overseers, or gangers, together with the quarters of such slaves as are employed for domestic purposes, whether as concubines or servants. On the other side stand the quarters of the ordinary slaves who labor on the plantation. They are built in long sheds, and in a few cases these are two stories high, but in most plantations only one. Some of the sheds are arranged like the dormitories in our barracks; sometimes the homes are almost or entirely isolated; sometimes, as in this roça, they are divided by partitions, like the stalls in a stable. At one end of the quadrangle, besides the magazines for the working and storage of the cocoa, there is a huge barn, which the slaves use as a kitchen, each family making its own little fire on the ground and cooking its rations separately, as the unconquerable habit of all natives is. At the other end of the quadrangle, sunk below the level of the fall of the hill, stands the hospital, with its male and female wards duly divided according to law.

SLAVE QUARTERS ON A PLANTATION

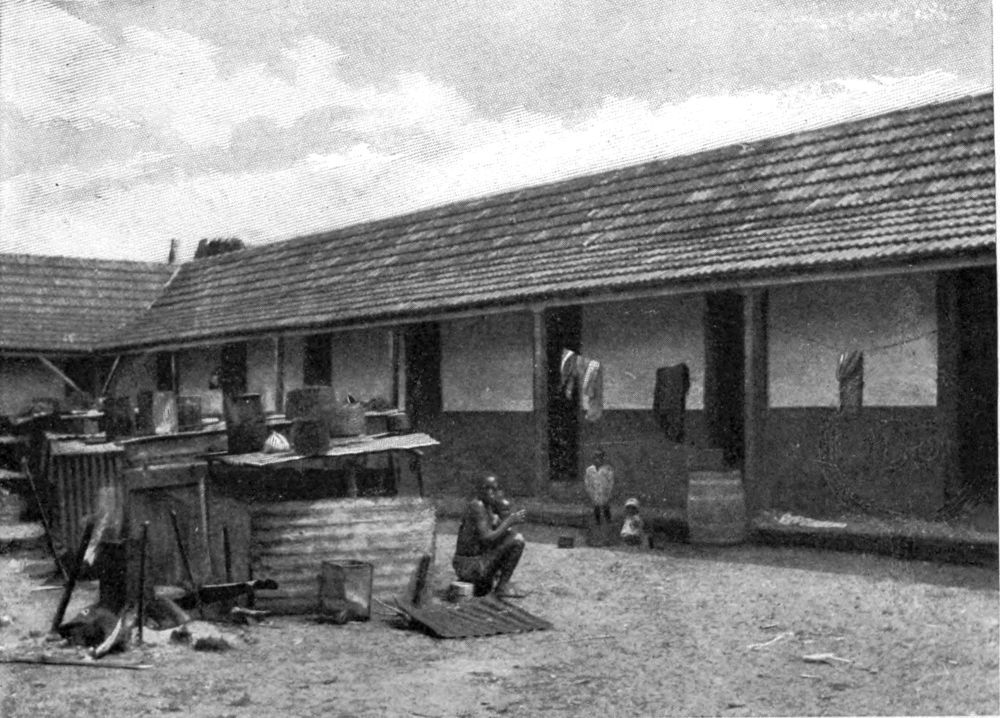

The centre of the quadrangle is occupied by great flat pans, paved with cement or stones, for the drying of the cocoa-beans. Within the largest of these enclosures the slaves are gathered two or three times a week to receive their rations of meal and dried fish. At six o’clock on the afternoon of my visit they all assembled to the clanging of the bell, the grown-up slaves bringing large bundles of grass, which they had gathered as part of their daily task, for the mules and cattle. They stood round the edges of the square in perfect silence. In the centre of the square at regular intervals stood the whity-brown gangers, leaning on their long sticks or flicking their boots with whips. Beside them lay the large and savage dogs which prowl round the buildings at night to prevent the slaves escaping in the darkness. As it was Sunday afternoon, the slaves were called upon to enjoy the Sunday treat. First came the children one by one, and to each of them was given a little sup of wine from a pitcher. Then the square began slowly to move round in single file. Slabs of dried fish were given out as rations, and for the special Sunday treat each man or woman received two leaves of raw tobacco from one of the superintendent’s mistresses, or, if they preferred it, one leaf of tobacco and a sup of wine in a mug. Nearly all chose the two leaves of tobacco as the more lasting joy. When they had received their dole, they passed round the square again in single file, till all had made the circuit. From first to last not a single word was spoken. It was more like a military execution than a festival.

About once a month the slaves receive their wages in a similar manner. By the Decree of 1903, the minimum wage for a man is fixed at 2500 reis (something under ten shillings) a month, and for a woman at 1800 reis. But, as a matter of fact, the planters tell me that the average wage is 1200 reis a month, or about one and twopence a week. In some cases the wages are higher, and one or two slaves were pointed out to me whose wages came to fifteen shillings a month. I am told that in the islands, unlike the custom on the mainland, these wages are really paid in cash and not by tokens, but the planters always add that as the money can only be spent in the plantation store, nearly all of it comes back to them in the form of profit on rum or cloth or food.

SLAVES WAITING FOR RATIONS ON SUNDAY

According to the law, only two-fifths of the wages are to be paid every month, the remaining three-fifths going to a “Repatriation Fund” in San Thomé. In the case of the slaves from Angola this is never done, and it is much to the credit of the Portuguese that, as there is no repatriation, they have dropped the institution of a Repatriation Fund. They might easily have pocketed three-fifths of the slaves’ wages under that excuse, but this advantage they have renounced. They never send the slaves home, and they do not deduct the money for doing it. Neither do they deduct a proportion of the wages which, according to the law, might be sent to the mainland for the support of a man’s family till the termination of his contract. They know a contract terminates only at death, and from this easy method of swindling they also abstain. It is, as I said, to their credit, the more because it is so unlike their custom.

For some reason which I do not quite understand—perhaps because they come under French government—the Cape Verde serviçaes receive a higher wage (three thousand reis for a man and twenty-five hundred for a woman); about a third is deducted every month for repatriation, and in many cases, at all events, the people are actually sent back. So the planters told me, though I have not seen them on a returning ship myself.

According to the law, the wages of all slaves must be raised ten per cent. if they agree to renew their contract for a second term of five years. With the best will in the world, it would be almost impossible to carry out this provision, for no slave ever does agree to renew his contract. His wishes in the matter are no more consulted than a blind horse’s in a coal-pit. The owner or Agent of the plantation waits till the five years of about fifty of his slaves have expired. Then he sends for the Curador from San Thomé, and lines up the fifty in front of him. In the presence of two witnesses and his secretary the Curador solemnly announces to the slaves that the term of their contract is up and the contract is renewed for five years more. The slaves are then dismissed and another scene in the cruel farce of contracted labor is over. One of the planters told me that he thought some of his slaves counted the years for the first five, but never afterwards.

Some planters do not even go through the form of bringing the Curador and the time-expired slaves face to face. They simply send down the papers for signature, and do not mention the matter to the slaves at all. At the end of June, 1905, a planter told me he had sent down the papers in April and had not yet received them back. He was getting a little anxious. “Of course,” he said, “it makes no difference whatever to the slaves. They know nothing about it. But I like to comply with the law.”

In one respect, however, that well-intentioned citizen did not comply with the law at all. The law lays it down that every owner of fifty slaves must set up a hospital with separate wards for the sexes. This man employed nearly two hundred slaves and had no hospital at all. The official doctor came up and visited the sick in their crowded huts twice a month.

The law lays it down that a crèche shall be kept on each plantation for children under seven, and certainly I have seen the little black infants herding about in the dust together among the empty huts while their parents were at work. Children are not allowed to be driven to work before they are eleven, and up to fourteen they may be compelled to do only certain kinds of labor. From fourteen to sixteen two kinds of labor are excluded—cutting timber and trenching the coffee. After sixteen they become full-grown slaves, and may be forced to do any kind of work. These provisions are only legal, but, as I noticed before, the children born on a plantation, if only they can be kept alive to maturity, ought to make the most valuable kind of slaves. Their keep has cost very little, and otherwise they come to the planter for nothing, like all good gifts of God. This is what makes me doubt the truth of a story one often hears about San Thomé, that a woman who is found to be with child after landing is flogged to death in the presence of the others. It is not the cruelty that makes me question it. Give a lonely white man absolute authority over blacks, and there is no length to which his cruelty may not go. But the loss in cash would be too considerable. At landing, a woman has cost the planter as much as two cows, and no good business man would flog a cow to death because she was in calf.

The same considerations tend, of course, to prevent all violent acts of cruelty such as might bring death. The cost of slaves is so large, the demand is so much greater than the supply, and the death-rate is so terrible in any case that a good planter’s first thought is to do all he can to keep his stock of slaves alive. It is true that in most men passion easily overcomes interest, and for an outsider it is impossible to judge of such things. When a stranger is coming, the word goes round that everything must be made to look as smooth and pleasant as possible. No one can realize the inner truth of the slave’s life unless he has lived many years on the plantations. But I am inclined to think that for business reasons the violent forms of cruelty are unlikely and uncommon. Flogging, however, is common if not universal, and so are certain forms of vice. The prettiest girls are chosen by the Agents and gangers as their concubines—that is natural. But it was worse when a planter pointed me out a little boy and girl of about seven or eight, and boasted that like most of the children they were already instructed in acts of bestiality, the contemplation of which seemed to give him a pleasing amusement amid the brutalizing tedium of a planter’s life.

In spite of all precautions and the boasted comfort of their lot, some of the slaves succeed in escaping. On San Thomé they generally take to highway robbery, and white men always go armed in consequence. The law decrees that a recaptured runaway is to be restored to his owner, and after the customary flogging he is then set to work again. Sometimes the runaways are hunted and shot down. On one of the mountains of San Thomé, I am told, you may still see a heap of bones where a party of runaway slaves were shot, but I have not seen them myself. For some reason, perhaps because of the greater wildness of the island, there are many more runaways on Principe, small as it is. The place is like a magic land, the dream of some wild painter. Points of cliff run sheer up from the sea, and between them lie secret little bays where a boat may be pushed off quietly over the sand. In one such bay, where the dense forest comes right down to the beach, a long canoe was gradually scooped out in January (1905) and filled with provisions for a voyage. When all was ready, eighteen escaped slaves launched it by night and paddled away into the darkness of the sea. For many days and nights they toiled, ignorant of all direction. They only knew that somewhere across the sea was their home. But before their provisions were quite spent, the current and the powers of evil that watch over slaves bore them to the coast of Fernando Po. Thinking they had reached freedom at last, they crept out of the boat on to the welcome shore, and there the authorities seized upon them, and, to the endless shame of Spain, packed them all on a steamer and sent them back in a single day to the place from which they came.

That is one of the things that make us anarchists. Probably there was hardly any one on Fernando Po, though it is a slave island itself, who would not willingly have saved those men if he had been left to his own instincts. But directly the state authority came in, their cause was hopeless. So it is that wherever you touch government you seem to touch the devil.

The eighteen were taken back to Principe, flogged almost to death in the jail, returned to their owners, and any of them who survive are still at work on the plantations, with but the memory of that brief happiness and overwhelming defeat to think upon.

When escaping slaves have reached the Cameroons, the Germans resolutely refuse to give them back, and by that refusal they have done much to cover the errors and harshness of their own colonial system. What would happen now to slaves who reached Nigeria or the Gold Coast, one hardly dares to think. There was a time when we used to hear fine stories of slaves falling on the beach when they touched British territory and kissing the soil of freedom. But that was long ago, and since then England has grown rich and fallen from her high estate. Her hands are no longer clean, and when people think of Johannesburg and Queensland and western Australia, all she may say of freedom becomes an empty sound, impressing no one.

Last April (1905) another of the planters discovered a party of eight of his own slaves just launching a canoe in hopes of escaping with better success. They had crammed the canoe with provisions—slaughtered pigs, meal, and water-casks—so many things that the planter told me it would certainly have sunk and drowned them all. To prevent this lamentable catastrophe he took them to the jail, had them flogged almost to death by the jailer there, and brought them back to the huts which they had so rashly attempted to leave in spite of their legal contract and their supposed willingness to work on the plantations.

In the interior, the island of Principe rises into great peaks, not so high as the mountains of San Thomé, but very much more precipitous. There is one peak especially where the rock falls so sheer that I think it would be inaccessible to the best climber on that side. I have not discovered the exact height of the mountains, but I should estimate them as something between four and five thousand feet, and they, like the whole island, are covered with forest and tropical growth, except where the rock is too steep and smooth to give any hold for roots. But, as a rule, one sees the mountains only by glimpses, for when I have passed the island or landed there they have always been wrapped in slowly moving mist, and I believe they are seldom clear of it. The mist falls in a soaking drizzle, and it seems to rain heavily, besides, almost every day, even in the dry season. Perhaps the moisture is almost too great, for I noticed more rot upon the cocoa-pods here than at San Thomé.

Into these dripping forests and almost inaccessible mountains the slaves are constantly trying to escape. A planter told me that many of them do not realize what an island is. They hope to be able to make their way home on foot. When they discover that the terrible sea foams all round them, they turn into the forest and build little huts, from which they are continually moving away. Here and there they plant little patches of maize or other food with seed which they steal from the plantations or which is secretly conveyed to them by the other slaves. Some kind of communication is evidently kept up, for it is thought the plantation slaves always know where the runaways are, and sometimes betray them. I saw one man who had been living with them in the forest himself and had come back with his hand cut off and his head split open, probably for treachery. We asked him the reason; we asked him to tell us something of the life out there; but at once he assumed the native’s impenetrable look and would not speak another word.

Women as well as men escape from time to time and join these fine vindicators of freedom in the woods, but, chiefly owing to the deadly climate and the extreme hardship of their life, the people do not increase in numbers. About a thousand was the highest figure I heard given for them; about two hundred the lowest. The number most generally quoted was six hundred, but, in fact, it is quite impossible to count them at all, for they are always changing their camps and are rarely seen. The cotton cloths in which they escape go to pieces very soon, and they all live in entire nakedness, except when the women take the trouble to string together a few plantain leaves as aprons. Among them, however, they have some clever craftsmen. They make good bows and arrows for hunting the civet-cats and other animals that form their chief food, and I have seen a two-handled saw made out of a common knife or matchet—a very ingenious piece of work. It was found in the hands of one of them who had been shot.

For the most part they live a wandering and hard, but I hope not an entirely unhappy, existence in the dense forest around the base of that precipitous mountain of which I spoke. Every now and again the Portuguese organize man-hunts to recapture or kill them off. Forming a kind of cordon, they sweep over parts of the island, tying up or shooting all they may find. But the Portuguese are so cowardly and incapable in their undertakings that they are no match for alert natives filled with the recklessness of despair, and the massacre has never yet been complete. In fact, the hunting-parties are often broken up by dissensions among rival strategists, and sometimes they appear to degenerate into convivial meetings, at which drink is the object and murder the excuse.

Recently, however, there was a very successful shoot. The sportsmen had been led by guides to a place where the escaped slaves were known to be rather thick in the forest. They came upon huts evidently just abandoned. Beside them, hidden in the grass, they found an old man. “We took him,” said the planter who told me the story, with all a sportsman’s relish, “and we forced him to tell us where the others were. At first we could not squeeze a word or sign out of him. After a long time, without saying anything, he lifted a hand towards the highest trees, and there we saw the slaves, men and women, clinging like bats to the under side of the branches. It was not long, I can tell you, before we brought them crashing down through the leaves on to the ground. My word, we had grand sport that day!”

I can imagine no more noble existence than has fallen to those poor and naked blacks, who have dared all for freedom, and, scorning the stall-fed life of slavery, have chosen rather to throw themselves upon such mercy as nature has, to wander together in nakedness and hunger from forest to forest and hut to hut, to live in daily apprehension of murder, to lurk like apes under the high branches, and at last to fall to the bullets of the Christians, dead, but of no further service to the commercial gentlemen who bought them and lose £30 by every death.

Even to the slaves who remain on the plantations, not having the courage or good-fortune to escape and die like wild beasts, death, as a rule, is not much longer delayed in coming. Probably within the first two or three years the slave’s strength begins to ebb away. With every day his work becomes feebler, so that at last even the ganger’s whip or pointed stick cannot urge him on. Then he is taken to the hospital and laid upon the boarded floor till he dies. An hour or so afterwards you may meet two of his fellow-slaves going into the forest. There is perhaps a sudden smell of carbolic or other disinfectant upon the air, and you take another look at the long pole the slaves are carrying between them on their shoulders. Under the pole a body is lashed, tightly wrapped up in the cotton cloth that was its dress while it lived. The head is covered with another piece of cloth which passes round the neck and is also fastened tightly to the pole. The feet and legs are sometimes covered, sometimes left to dangle naked. In silence the two slaves pass into some untrodden part of the forest, and the man or woman who started on life’s journey in a far-off native village with the average hope and delight of childhood, travels over the last brief stage and is no more seen.

Laws and treaties do not count for much. A law is never of much effect unless the mind of a people has passed beyond the need of it, and treaties are binding only on those who wish to be bound. But still there are certain laws and treaties that we may for a moment recall: in 1830 England paid £300,000 to the Portuguese provided they forbade all slave-trade—which they did and pocketed the money; in 1842 England and the United States agreed under the Ashburton Treaty to maintain joint squadrons on the west coast of Africa for the suppression of the slave-trade; in 1858 Portugal enacted a law that every slave belonging to a Portuguese subject should be free in twenty years; in 1885, by the Berlin General Act, England, the United States, and thirteen other powers, including Portugal and Belgium, pledged themselves to suppress every kind of slave-trade, especially in the Congo and the interior of Africa; in 1890, by the Brussels General Act, England, the United States, and fifteen other powers, including Portugal and Belgium, pledged themselves to suppress every kind of slave-trade, especially in the Congo and the interior of Africa, to erect cities of refuge for escaped slaves, to hold out protection to every fugitive slave, to stop all convoys of slaves on the march, and to exercise strict supervision at all ports so as to prevent the sale or shipment of slaves across the sea.

If any one wanted a theme for satire, what more deadly theme could he find?

To which of the powers can appeal now be made? Appeal to England is no longer possible. Since the rejection of Ireland’s home-rule bill, the abandonment of the Armenians to massacre, and the extinction of the South-African republics, she can no longer be regarded as the champion of liberty or of justice among mankind. She has flung away her only noble heritage. She has closed her heart of compassion, and for ten years past the oppressed have called to her in vain. A single British cruiser, posted off the coast of Angola, with orders to arrest every mail-boat or other ship having serviçaes on board, would so paralyze the system that probably it would never recover. But one might as soon expect Russia or Germany to do it as England in her recent mood. She will make representations, perhaps; she will remind Portugal of “the old alliance” and the friendship between the royal families; but she will do no more. What she says can have no effect; her tongue, which was the tongue of men, has become like sounding brass; and if she spoke of freedom, the nations would listen with a polished smile.

From her we can turn only to America. There the sense of freedom still seems to linger, and the people are still capable of greater actions than can ever be prompted by commercial interests and the search for a market. America’s record is still clean compared to England’s, and her impulses to compassion and justice will not be checked by family affection for the royalties of one out of the two most degraded, materialized, and unintellectual little states of Europe. America may still take the part that once was England’s by right of inheritance. She may stand as the bulwark of freedom against tyranny, and of justice and mercy—those almost extinct qualities—against the restless greed and blood-thirsty pleasure-seeking of the world. Let America declare that her will is set against slavery, and at her voice the abominable trade in human beings between Angola and the islands will collapse as the slave-trade to Brazil collapsed at the voice of England in the days of her greatness.

I am aware that, as I said in my first letter, the whole question of slavery is still before us. It has reappeared under the more pleasing names of “indentured labor,” “contract labor,” or the “compulsory labor” which Mr. Chamberlain has advocated in obedience to the Johannesburg mine-owners. The whole thing will have to be faced anew, for the solutions of our great-grandfathers no longer satisfy. While slavery is lucrative, as it is on the islands of San Thomé and Principe, it will be defended by those who identify greatness with wealth, and if their own wealth is involved, their arguments will gain considerably in vigor. They will point to the necessity of developing rich islands where no one would work without compulsion. They will point to what they call the comfort and good treatment of the slaves. They will protect themselves behind legal terms. But they forget that legal terms make no difference to the truth of things. They forget that slavery is not a matter of discomfort or ill treatment, but of loss of liberty. They forget that it might be better for mankind that the islands should go back to wilderness than that a single slave should toil there. I know the contest is still before us. It is but part of the great contest with capitalism, and in Africa it will be as long and difficult as it was a hundred years ago in other regions of the world. I have but tried to reveal one small glimpse in a greater battle-field, and to utter the cause of a few thousands out of the millions of men and women whose silence is heard only by God. And perhaps if the crying of their silence is not heard even by God, it will yet be heard in the souls of the just and the compassionate.