IX

THE EXPORTATION OF SLAVES

When I was up in the interior, I had always intended to wait a while on the coast, if ever I should reach it again, in order to watch the process of the conversion of slaves into “contracted laborers” according to law. So it was fortunate that, owing to the delays of fevers and carriers, I succeeded in just missing a steamer bound for San Thomé and home. Fortunate, because the temptation to go straight on board would have been very strong, since I was worn with sickness, and within two days of reaching Katumbella I learned that special dangers surrounded me, owing to the discovery of my purpose by the Portuguese traders. As a matter of fact, I might have caught the ship by pushing my carriers on without a pause, but the promptings of conscience, supported by a prospect of the best crocodile-shooting that man can enjoy, induced me to run the risk of assassination and stay.

So I stayed on the coast for nearly three weeks, seeing what I could, hunting crocodiles, and devising schemes for getting my papers home even if I should never reach home myself. One of the first things I saw was a procession of slaves who had just been “redeemed” into “contracted laborers,” and were being marched off in the early morning sunlight from Katumbella to Lobito Bay, there to be embarked for San Thomé on the ship which I had missed.[11] It so happened that this ship put in at Lobito Bay, which lies only some eight miles north from Katumbella down a waterless spit of sand, as I have before described, and there can be no doubt that this practice will become more and more common as the railway from the new port progresses. Katumbella, united with the bay, will become the main depot for the exportation of slaves and other merchandise, while Benguela, having no natural harbor, will gradually fall to ruin. At present, I suppose, the government Agent for slaves at Benguela, together with the Curador, whose act converts them into contract laborers, comes over for the occasion whenever the slaves are to be shipped from Lobito Bay, just as in England a bishop travels from place to place for Confirmations as required.

Bemused with a parting dole of rum, bedecked in brilliantly striped jerseys, grotesque caps, and flashy loin-cloths to give them a moment’s pleasure, the unhappy throng were escorted to their doom, the tin tickets with their numbers and the tin cylinders with their form of contract glittering round their necks or at their sides. Men and women were about equal in number, and some of the women carried babes lashed to their backs; but there were no older children. The causes which had brought these men and women to their fate were probably as different as the lands from which they came. Some had broken native customs or Portuguese laws, some had been charged with witchcraft by the medicine-man because a relative died, some could not pay a fine, some were wiping out an ancestral debt, some had been sold by uncles in poverty, some were the indemnity for village wars; some had been raided on the frontier, others had been exchanged for a gun; some had been trapped by Portuguese, others by Bihéan thieves; some were but changing masters, because they were “only good for San Thomé,” just as we in London send an old cab-horse to Antwerp. I cannot give their history. I only know that about two hundred of them, muddled with rum and bedecked like clowns, passed along that May morning to a land of doom from which there was no return.

It was June 1st when, as I described in my last letter, I met that other procession of slaves on their way from Katumbella to Benguela, in readiness for embarkation in the next ship, which did not happen to stop at Lobito Bay. It was a smaller gang—only forty-three men and women—for it was the result of only one Agent’s activity, though, to be sure, he was the leading and most successful Agent in Angola. They marched under escort, but without loads and without chains, though the old custom of chaining them together along that piece of road is still commonly practised—I suppose because the fifteen miles of country through which the road leads, when once the small slave-plantations round Katumbella have been passed, is a thorny desert where a runaway might easily hide, hoping to escape by sea or find cover in the towns. I have myself seen the black soldiers or police searching the bush there for fugitives, and once I found a Portuguese dying of fever among the thorns, to which he had fled from what is roughly called justice.[12]

By the time I saw that second procession I was myself living in Benguela, and was able to follow the slave’s progress almost point by point, in spite of the uncomfortable suspicion with which I was naturally regarded. Writing of the town before, I mentioned the large court-yards with which nearly every house is surrounded—memorials of the old days when this was the central depot for the slave-trade with Brazil. In most cases these court-yards are now used as resting-places for the free carriers who have brought products from the interior and are waiting till the loads of cloth and rum are ready for the return journey. But the trading-houses that go in for business in “serviçaes” still put the court-yards to their old purpose, and confine the slaves there till it is time to get them on board.

A day or two before the steamer is due to depart a kind of ripple seems to pass over the stagnant town. Officials stir, clerks begin to crawl about with pens, the long, low building called the Tribunal opens a door or two, a window or two, and looks quite busy. Then, early one morning, the Curador arrives and takes his seat in the long, low room as representing the beneficent government of Portugal. Into his presence the slaves are herded in gangs by the official Agent. They are ranged up, and in accordance with the Decree of January 29, 1903, they are asked whether they go willingly as laborers to San Thomé. No attention of any kind is paid to their answer. In most cases no answer is given. Not the slightest notice would be taken of a refusal. The legal contract for five years’ labor on the island of San Thomé or Principe is then drawn out, and, also in accordance with the Decree, each slave receives a tin disk with his number, the initials of the Agent who secured him, and in some cases, though not usually at Benguela, the name of the island to which he is destined. He also receives in a tin cylinder a copy of his register, containing the year of contract, his number and name, his birthplace, his chief’s name, the Agent’s name, and “observations,” of which last I have never seen any. Exactly the same ritual is observed for the women as for the men. The disks are hung round their necks, the cylinders are slung at their sides, and the natives, believing them to be some kind of fetich or “white man’s Ju-ju,” are rather pleased. All are then ranged up and marched out again, either to the compounds, where they are shut in, or straight to the pier where the lighters, which are to take them to the ship, lie tossing upon the waves.

The climax of the farce has now been reached. The deed of pitiless hypocrisy has been consummated. The requirements of legalized slavery have been satisfied. The government has “redeemed” the slaves which its own Agents have so diligently and so profitably collected. They went into the Tribunal as slaves, they have come out as “contracted laborers.” No one in heaven or on earth can see the smallest difference, but by the change of name Portugal stifles the enfeebled protests of nations like the English, and by the excuse of law she smooths her conscience and whitens over one of the blackest crimes which even Africa can show.

Before I follow the slaves on board, I must raise one uncertain point about the Agents. I am not quite sure on what principle they are paid. According to the Decree of 1903, they are appointed by the local committee in San Thomé, consisting of four officials and three planters, chosen by the central government Committee of Emigration in Lisbon. The local committee has to fix the payment due to each Agent, and of course the payment is ultimately made by the planters, who requisition the local committee for as many slaves as they require, and pay in proportion to the number they receive. Now a planter in San Thomé gives from £26 to £30 for a slave delivered on his plantation in good condition. The Agent at Benguela will give £16 for any healthy man or woman brought to him, but he rarely goes up to £20. From this considerable profit balance of £10 to £14 per head there are, it is true, certain deductions to be made. By the Decree, each Agent has to pay the government £100 deposit before he sets up in the slave-dealing business, and most probably he recoups himself out of the profits. For his license he has to pay the government two shillings a slave (with a minimum payment of £10 a year). Also to the government he pays £1 per slave in stamp duty, and six shillings on the completion of each contract. He has further to pay a tax of six shillings per slave to the port of landing, and from the balance of profit we must also deduct the slave’s fare on the steamer from Benguela to San Thomé. This, I believe, is £2—a sum which goes to enrich the happy shareholders in the “Empreza Nacional,” who last year (1904) received twenty-two per cent. on their money as profit from the slave-ships. Then the captain of the steamer gets four shillings and the doctor two shillings for every slave landed alive, and, on an average, only four slaves per hundred die on the voyage, which takes about eight days. There are probably other deductions to be made. The Curador will get something for his important functions. There are stories that the commandants of certain forts still demand blackmail from the processions of slaves as they go by. I was definitely told that the commandant of a fort very near to Benguela always receives ten shillings a head, but I cannot say if that is true.

In any case, at the very lowest, there is £4 to be deducted for fare, taxes, etc., from the apparent balance of £10 to £14 per slave. But even then the profit on each man or woman sold is considerable, and the point that I am uncertain about is whether the Agent at Benguela and his deputies in Novo Redondo and Bihé pocket all the profit they can possibly make, or are paid a fixed proportion of the average profits by the local committee at San Thomé. The latter would be in accordance with the Decree; the other way more in accordance with Portuguese methods.

Unhappily I was not able to witness the embarkation of the slaves myself, as I had been poisoned the night before and was suffering all day from violent pain and frequent collapse, accompanied by extreme cold in the limbs.[13] So that when, late in the evening, I crawled on board at last, I found the slaves already in their place on the ship. We were taking only one hundred and fifty of them from Benguela, but we gathered up other batches as we went along, so that finally we reached a lucrative cargo of two hundred and seventy-two (not counting babies), and as only two of them died in the week, we landed two hundred and seventy safely on the islands. This was perhaps rather a larger number than usual, for the steamers, which play the part of mail-boats and slave-ships both, go twice a month, and the number of slaves exported by them yearly has lately averaged a little under four thousand, though the numbers are increasing, as I showed in my last letter.

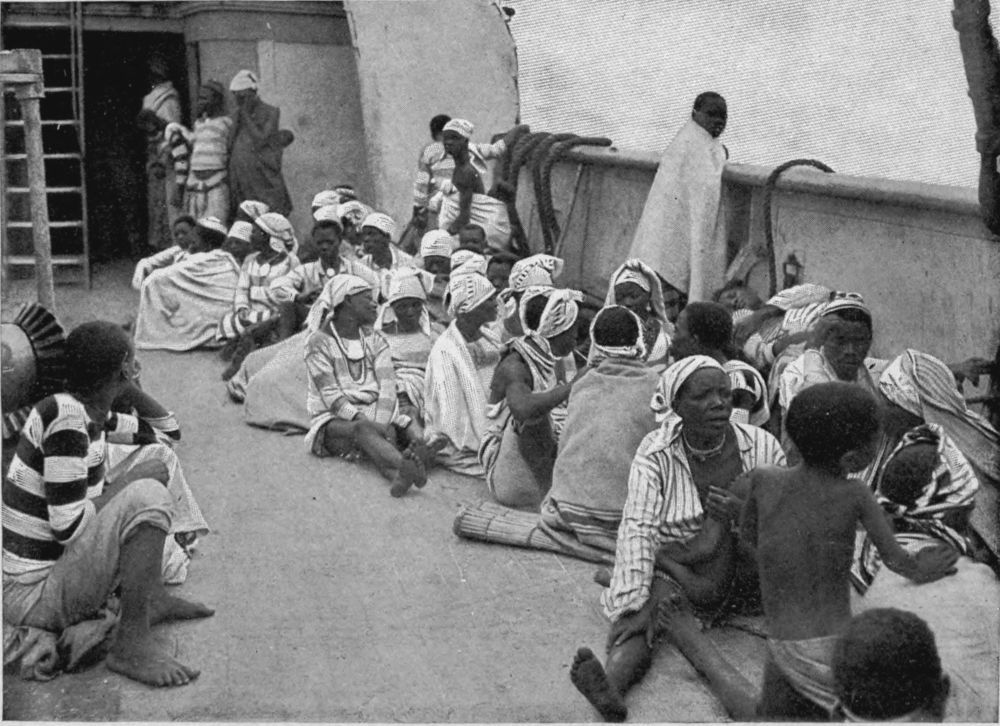

The slaves are, of course, kept in the fore part of the ship. All day long they lie about the lower deck, among the horses, mules, cattle, sheep, monkeys, and other live-stock; or they climb up to the fo’c’s’le deck in hopes of getting a little breeze, and it is there that the mothers chiefly lie beside their tiny babies. There is nothing to do. Hardly any one speaks, and over the faces of nearly all broods the look of dumb bewilderment that one sees in cattle crowded into trucks for the slaughter-market. Twice a day rations of mealy pap or brown beans are issued in big pots. Each pot is supplied with ten wooden spoons and holds the food for ten slaves, who have to get as much of it as each can manage. The first-class passengers, leaning against the rail of the upper deck, look down upon the scene with interest and amusement. To them those slaves represent the secret of Portugal’s greatness—such greatness as Portugal has.

“ALL DAY LONG THEY LIE ABOUT THE LOWER DECK”

At sunset they are herded into a hold, the majority going down the hatchway stairs on their hands and knees. There they spread their sleeping-mats, and the hatch is shut down upon them till the following morning. By the virtuous Decree of 1903, which regulates the transport, “the emigrants [i.e., the slaves] shall be separated according to sex into completely isolated compartments, and may not sleep on deck, nor resume conjugal relations before leaving the ship.” Certainly the slaves do not sleep on deck, but as to the other clauses I have seen no attempt to carry out the regulations, except such measures as the slaves take themselves by dividing the hold between men and women. It may seem strange, but all my observation has shown me that, in spite of nakedness and the absence of shame in most natural affairs of existence, the natives are far more particular about the really important matters of sex than civilized people are; just as most animals are far more particular, and for the same reasons. I mean that for them the difference of sex is mainly a matter of livelihood and child-getting, not of casual debauchery.

Even a coast trader said to me one evening, as we were looking down into the hold where the slaves were arranging their mats, “What a different thing if they were white people!”

The day after leaving Benguela we stopped off Novo Redondo to take on more cargo. The slaves came off in two batches—fifty in the morning and thirty more towards sunset. There was a bit of a sea on that day, and the tossing of the lighter had made most of the slaves very sick. Things became worse when the lighter lay rising and falling with the waves at the foot of the gangway, and the slaves had to be dragged up to the platform one by one like sacks, and set to climb the ladder as best they could. I remember especially one poor woman who held in her arms a baby only two or three days old. Quickly as native women recover from childbirth, she had hardly recovered, and was very sea-sick besides. In trying to reach the platform, she kept on missing the rise of the wave, and was flung violently back again into the lighter. At last the men managed to haul her up and set her on the foot of the ladder, striking her sharply to make her mount. Tightening the cloth that held the baby to her back, and gathering up her dripping blanket over one arm, she began the ascent on all-fours. Almost at once her knees caught in the blanket and she fell flat against the sloping stairs. In that position she wriggled up them like a snake, clutching at each stair with her arms above her head. At last she reached the top, bruised and bleeding, soaked with water, her blanket lost, most of her gaudy clothing torn off or hanging in strips. On her back the little baby, still crumpled and almost pink from the womb, squeaked feebly like a blind kitten. But swinging it round to her breast, the woman walked modestly and without complaint to her place in the row with the others.

I have heard many terrible sounds, but never anything so hellish as the outbursts of laughter with which the ladies and gentlemen of the first class watched that slave woman’s struggle up to the deck.

When all the slaves were on board at last, a steward or one of the ship’s officers mustered them in a row, and the ship’s doctor went down the line to perform the medical examination, in accordance with Chapter VI. of the Decree, enacting that no diseased or infectious person shall be accepted. It is entirely to the doctor’s interest to foster the health of the slaves, for, as I have already mentioned, every death loses him two shillings. As a rule, as I have said, he loses four per cent. of his cargo, or two dollars out of every possible fifty. On this particular voyage, however, he was more fortunate, for only two slaves out of the whole number died during the week, and were thrown overboard during the first-class breakfast-hour, so that the feelings of the passengers might not be harrowed.

Next day after leaving Novo Redondo we reached Loanda and increased our cargo by forty-two men and women, all tricked out in the most amazing tartan plaids—the tartans of Israel in the Highlands. This made up our total number of two hundred and seventy-two, not reckoning babies, which, unhappily, I did not count. Probably there were about fifty. I think neither the captain nor the doctor receives any percentage for landing babies alive, but, of course, if they live to grow up on the plantations, which is very seldom, they become even more valuable than the imported adults, and the planter gets them gratis.

Early next morning, when we were anchored off Ambriz, a commotion suddenly arose on board, and the rumor ran that one of the slaves had jumped into the sea from the bow. Soon we could see his black head as he swam clear of the ship and struck out southwards, apparently trusting to the current to bear him towards the coast. For he was a native of a village near Ambriz and knew what he was about. It was yearning at the sight of his own land that made him run the risk. The sea was full of sharks, and I could only hope that they might devour him before man could seize him again. Already a boat had been hastily dropped into the water and was in pursuit, manned by two black men and a white. They rowed fast over the oily water, and the swimmer struggled on in vain. The chase lasted barely ten minutes and they were upon him. Leaning over the side of the boat, they battered him with oars and sticks till he was quiet. Then they dragged him into the boat, laid him along the bottom, and stretched a piece of old sail over his nakedness, that the ladies might not be shocked. He was brought to the gangway and dragged, dripping and trembling, up the stairs. The doctor and the government Agent, who accompanies each ship-load of slaves, took him down into the hold, and there he was chained up to a post or staple so that he might cause no trouble again. “Flog him! Flog him! A good flogging!” cried the passengers. “Boa chicote!” I have not the slightest doubt he was flogged without mercy, but if so, it was kept secret—an unnecessary waste of pleasure, for the passengers would thoroughly have enjoyed both the sight and sound of the lashing. The comfortable and educated classes in all nations appear not to have altered in the least since the days when the comfortable and educated classes of Paris used to arrange promenades to see the Communards shot in batches against a wall. They may whine and blubber over imaginary sufferings in novels and plays, but touch their comfort, touch their property—they are rattlesnakes then!

We stopped at Cabinda in the Portuguese territory north of the Congo, and at one or two other trading-places on the coast, and then we put out northwest for the islands. On the eighth day after leaving Benguela we came in sight of San Thomé. Over it the sky was a broken gray of drifting rain-clouds. Only now and again we could see the high peaks of the mountains, which run up to seven thousand feet. The valleys at their base were shrouded in the pale and drizzling mists which hang about them almost continually. Here and there a rounded hill, indigo with forest, rose from the mists and showed us the white house of some plantation and the little cluster of out-buildings and huts where the slaves were to find their new home. Then, as on an enchanted island, the ghostly fog stole over it again, and in another quarter some fresh hill, indigo with forest, stood revealed.

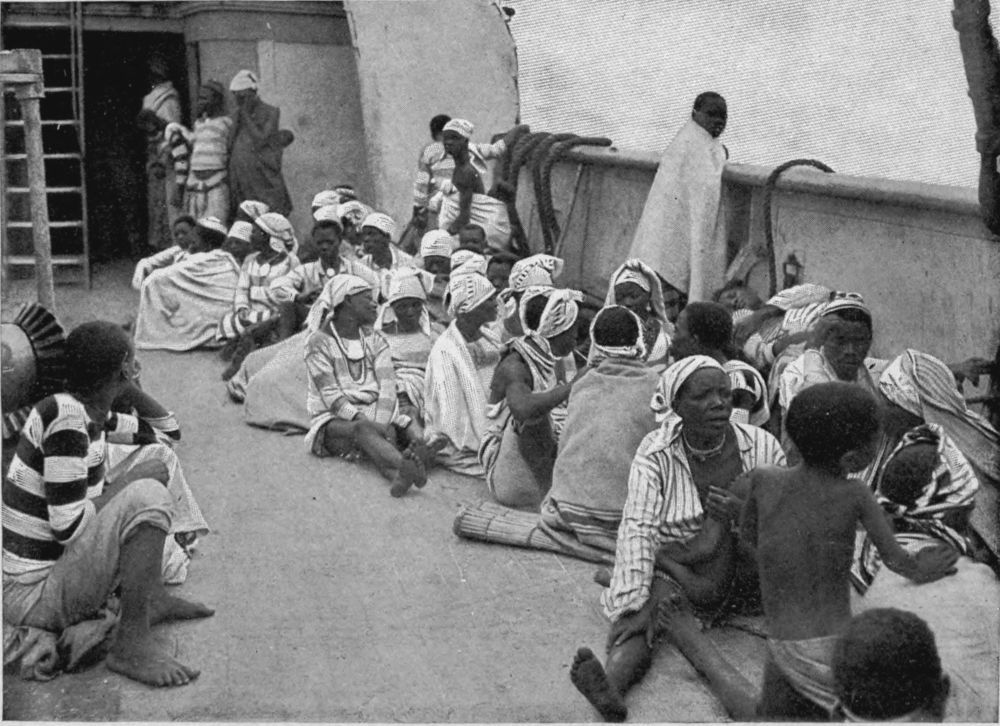

THE WOMEN HARDLY STIRRED AS WE APPROACHED SAN THOMÉ

The whole place smoked and steamed like a gigantic hot-house. In fact, it is a gigantic hot-house. As nearly as possible, it stands upon the equator, the actual line passing through the volcanic rocks of its southern extremity. And even in the dry season from April to October it is perpetually soaked with moisture. The wet mist hardly ceases to hang among the hills and forest trees. The thick growth of the tropics covers the mountains almost to their summits, and every leaf of verdure drips with warm dew.

The slaves on deck regarded the scene with almost complete apathy. Some of the men leaned against the bulwark and silently watched the points of the island as we passed. The women hardly stirred from their places. They were occupied with their babies as usual, or lay about in the unbroken wretchedness of despair. Two girls of about fifteen or sixteen, evidently sisters, whom I had before noticed for a certain pathetic beauty, now sat huddled together hand-in-hand, quietly crying. They were just the kind of girls that the planters select for their concubines, and I have little doubt they are the concubines of planters now. But they cried because they feared they would be separated when they came to land.

In the confusion of casting anchor I stood by them unobserved, and in a low voice asked them a few questions in Umbundu, which I had crammed up for the purpose. The answers were brief, in sobbing whispers; sometimes by gestures only. The conversation ran like this:

“Why are you here?”

“We were sold to the white men.”

“Did you come of your own free will?”

“Of course not.”

“Where did you come from?”

“From Bihé.”

“Are you slaves or not?”

“Of course we are slaves!”

“Would you like to go back?”

The delicate little brown hands were stretched out, palms downward, and the crying began afresh.

That night the slaves were left on board, but next morning (June 17th) when I went down to the pier about nine o’clock, I found them being landed in two great lighters. One by one the men and women were dragged up on to the pier by their arms and loin-cloths and dumped down like bales of goods. There they sat in four lines till all were ready, and then, carrying their mats and babies, they were marched off in file to the Curador’s house in the town beside the bay. Here they were driven through large iron gates into a court-yard and divided up into gangs according to the names of the planters who had requisitioned for them. When the parties were complete, they were put under the charge of gangers belonging to various plantations, and so they set out on foot upon the last stage of their journey. When they reached their plantation (which would usually be on the same day or the next, for the island is only thirty-five miles long by fifteen broad) they would be given a day or two for rest, and then the daily round of labor would begin. For them there are no more journeyings, till that last short passage when their dead bodies are lashed to poles and carried out to be flung away in the forest.

LINED UP ON THE PIER AT SAN THOMÉ

NOTE.—I have no direct evidence that the poison was given me intentionally, but the “cumulative” evidence is rather strong. While still in the interior I had been warned that the big slave-dealers had somehow got to know of my purpose and were plotting against me. On the coast the warnings increased, till my life became almost as ludicrous as a melodrama, and I was obliged to “live each day as ’twere my last”—an unpleasant and unprofitable mode of living. One man would drop hints, another would give instances of Portuguese treachery. I was often told the fate of a poor Portuguese trader named De Silva, who objected to slavery and was going to Lisbon to expose the system, but after his first meal on board was found dead in his cabin. People in the street whispered of my fate. A restaurant-keeper at Benguela told an English fellow-passenger on my ship that he had better not be seen with me, for I was in great danger. My boy, who had followed me right through from the Gold Coast with the fidelity of a homeless dog, kept bringing me rumors of murder that he heard among the natives. Two nights before the ship sailed I was at a dinner given by the engineers of the new railway, and into my overcoat-pocket some one, whom I wish publicly to thank, tucked a scrap of paper with the words, “You are in great peril,” written in French. If there was a plot to set upon me in the empty streets that night, it was prevented by an Englishman who volunteered to go back with me, though I had not told him of any danger. Next night I was poisoned. Owing to the frequent warnings, I was ready with antidotes, but I think I should not have reached the ship alive next day without the courageous and devoted help of a South-African prospector who had been shut up with me in Ladysmith. The Dutch trader with whom I was staying was himself far above suspicion, but I shall not forget his indignant excitement when he saw what had happened. Evidently it was what he had feared, though I only told him I must have eaten something unwholesome. The tiresome sense of apprehension lasted during my voyage to the islands, and I was obliged to keep a dyspeptic watch upon the food. But I do not wish to make much of these little personal matters. To American and English people in their security they naturally seem absurd, and as a proof how common the art of poisoning still is in Portuguese possessions I will only mention that I have met a Portuguese trader in San Thomé who carries about in his waistcoat a little packet of pounded glass which he detected one evening in his soup, and that on the Portuguese ship which finally took me from San Thomé to Lisbon a Portuguese official died the day we started, from an illness due to his belief that he was being poisoned, and that during the voyage a poor Belgian from the interior gradually faded away under the same belief, and was carried out at Lisbon in a dying condition. Of course both may have been mad, but even madness does not take that form without something to suggest it.