I

INTRODUCTORY

For miles on miles there is no break in the monotony of the scene. Even when the air is calmest the surf falls heavily upon the long, thin line of yellow beach, throwing its white foam far up the steep bank of sand. And beyond the yellow beach runs the long, thin line of purple forest—the beginning of that dark forest belt which stretches from Sierra Leone through West and Central Africa to the lakes of the Nile. Surf, beach, and forest—for two thousand miles that is all, except where some great estuary makes a gap, or where the line of beach rises to a low cliff, or where a few distant hills, leading up to Ashanti, can be seen above the forest trees.

It is not a cheerful part of the world—“the Coast.” Every prospect does not please, nor is it only man that is vile. Man, in fact, is no more vile than elsewhere; but if he is white he is very often dead. We pass in succession the white man’s settlements, with their ancient names so full of tragic and miserable history—Axim, Sekundi, Cape Coast Castle, and Lagos. We see the old forts, built by Dutch and Portuguese to protect their trade in ivory and gold and the souls of men. They still gleam, white and cool as whitewash can make them, among the modern erections of tin and iron that have a meaner birth. And always, as we pass, some “old Coaster” will point to a drain or an unfinished church, and say, “That was poor Anderson’s last bit.” And always when we stop and the officials come off to the ship, drenched by the surf in spite of the skill of native crews, who drive the boats with rapid paddles, hissing sharply at every stroke to keep the time—always the first news is of sickness and death. Its form is brief: “Poor Smythe down—fever.” “Poor Cunliffe gone—black-water.” “Poor Tompkinson scuppered—natives.” Every one says, “Sorry,” and there’s no more to be said.

It is not cheerful. The touch of fate is felt the more keenly because the white people are so few. For the most part, they know one another, at all events by classes. A soldier knows a soldier. Unless he is very military, indeed, he knows the district commissioner, and other officials as well. An official knows an official, and is quite on speaking terms with the soldiers. A trader knows a trader, and ceases to watch him with malignant jealousy when he dies. It is hard to realize how few the white men are, scattered among the black swarms of the natives. I believe that in the six-mile radius round Lagos (the largest “white” town on the Coast) the whites could not muster one hundred and fifty among the one hundred and forty thousand blacks. And in the great walled city of Abeokuta, to which the bit of railway from Lagos runs, among a black population of two hundred and five thousand, the whites could hardly make up twenty all told. So that when one white man disappears he leaves a more obvious gap than he would in a London street, and any white man may win a three days’ fame by dying.

Among white women, a loss is naturally still more obvious and deplorable. Speaking generally, we may say the only white women on the Coast are nurses and missionaries. A benevolent government forbids soldiers and officials to bring their wives out. The reason given is the deadly climate, though there are other reasons, and an exception seems to be made in the case of a governor’s wife. She enjoys the liberty of dying at her own discretion. But Accra, almost alone of the Coast towns, boasts the presence of two or three English ladies, and I have known men overjoyed at being ordered to appointments there. Not that they were any more devoted to the society of ladies than we all are, but they hoped for a better chance of surviving in a place where ladies live. Vain hope; in spite of cliffs and clearings, in spite of golf and polo, and ladies, too, Death counts his shadows at Accra much the same as anywhere else.

You never can tell. I once landed on a beach where it seemed that death would be the only chance of comfort in the tedious hell. On either hand the flat shore stretched away till it was lost in distance. Close behind the beach the forest swamp began. Upon the narrow ridge nine hideous houses stood in the sweltering heat, and that was all the town. The sole occupation was an exchange of palm-oil for the deadly spirit which profound knowledge of chemistry and superior technical education have enabled the Germans to produce in a more poisonous form than any other nation. The sole intellectual excitement was the arrival of the steamers with gin, rum, and newspapers. Yet in that desolation three European ladies were dwelling in apparent amity, and a volatile little Frenchman, full of the joy of life, declared he would not change that bit of beach—no, not for all the cafés chantants of his native Marseilles. “There is not one Commandment here!” he cried, unconsciously imitating the poet of Mandalay; and I suppose there is some comfort in having no Commandments, even where there is very little chance of breaking any.

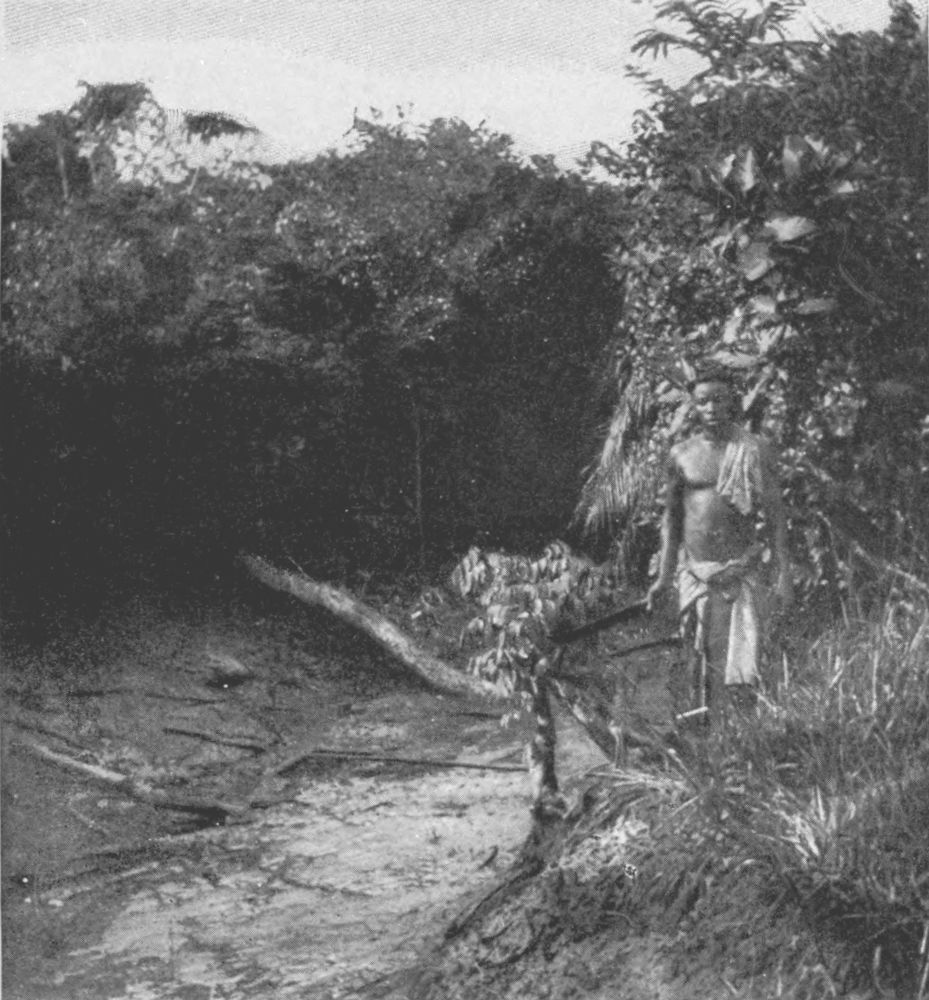

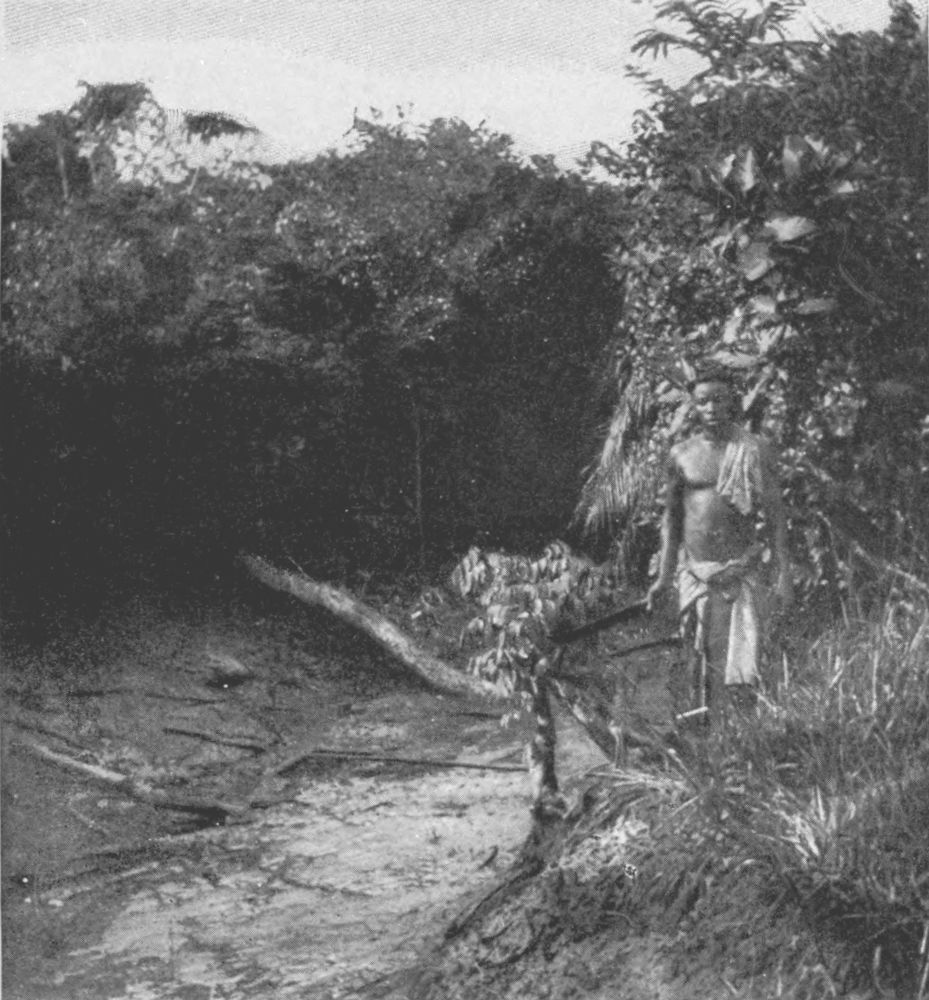

The farther down the Coast you go the more melancholy is the scene. The thin line of yellow beach disappears. The forest comes down into the sea. The roots of the trees are never dry, and there is no firm distinction of land and water. You have reached “the Rivers,” the delta of the Niger, the Circle of the mangrove swamps, in which Dante would have stuck the Arch-Traitor head downward if only he had visited this part of the world. I gained my experience of the swamps early, but it was thorough. It was about the third time I landed on the Coast. Hearing that only a few miles away there was real solid ground where strange beasts roamed, I determined to cut a path through the forest in that direction. Engaging two powerful savages armed with “matchets,” or short, heavy swords, I took the plunge from a wharf which had been built with piles beside a river. At the first step I was up to my knees in black sludge, the smell of which had been accumulating since the glacial period. Perhaps the swamps are forming the coal-beds of a remote future; but in that case I am glad I did not live at Newcastle in a remote past. As in a coronation ode, there seemed no limit to the depths of sinking. One’s only chance was to strike a submerged trunk not yet quite rotten enough to count as mud. Sometimes it was possible to cling to the stems or branches of standing trees, and swing over the slime without sinking deep. It was possible, but unpleasant; for stems and branches and twigs and fibres are generally covered with every variety of spine and spike and hook.

In a quarter of an hour we were as much cut off from the world as on the central ocean. The air was dark with shadow, though the tree-tops gleamed in brilliant sunshine far above our heads. Not a whisper of breeze nor a breath of fresh air could reach us. We were stifled with the smell. The sweat poured from us in the intolerable heat. Around us, out of the black mire, rose the vast tree trunks, already rotting as they grew, and between the trunks was woven a thick curtain of spiky plants and of the long suckers by which the trees draw up an extra supply of water—very unnecessarily, one would have thought.

Through this undergrowth the natives, themselves often up to the middle in slime, slowly hacked a way. They are always very patient of a white man’s insanity. Now and then we came to a little clearing where some big tree had fallen, rotten from bark to core. Or we came to a “creek”—one of the innumerable little watercourses which intersect the forest, and are the favorite haunt of the mud-fish, whose eyes are prominent like a frog’s, and whose side fins have almost developed into legs, so that, with the help of their tails, they can run over the slime like lizards on the sand. But for them and the crocodiles and innumerable hosts of ants and slugs, the lower depths of the mangrove swamp contain few living things. Parrots and monkeys inhabit the upper world where the sunlight reaches, and sometimes the deadly stillness is broken by the cry of a hawk that has the flight of an owl and fishes the creeks in the evening. Otherwise there is nothing but decay and stench and creatures of the ooze.

AN AFRICAN SWAMP

After struggling for hours and finding no change in the swamp and no break in the trees, I gave up the hope of that rising ground, and worked back to the main river. When at last I emerged, sopping with sweat, black with slime, torn and bleeding from the thorns, I knew that I had seen the worst that nature can do. I felt as though I had been reforming the British War Office.

It is worth while trying to realize the nature of these wet forests and mangrove swamps, for they are the chief characteristic of “the Coast” and especially of “the Rivers.” Not that the whole even of southern Nigeria is swamp. Wherever the ground rises, the bush is dry. But from a low cliff, like “The Hill” at Calabar, although in two directions you may turn to solid ground where things will grow and man can live, you look south and west over miles and miles of forest-covered swamp that is hopeless for any human use. You realize then how vain is the chatter about making the Coast healthy by draining the mangrove swamps. Until the white man develops a new kind of blood and a new kind of inside, the Coast will kill him. Till then we shall know the old Coaster by the yellow and streaky pallor of a blood destroyed by fevers, by a confused and uncertain memory, and by a puffiness that comes from enfeebled muscle quite as often as from insatiable thirst.

It is through swamps like these that those unheard-of “punitive expeditions” of ours, with a white officer or two, a white sergeant or two, and a handful of trusty Hausa men, have to fight their way, carrying their Maxim and three-inch guns upon their heads. “I don’t mind as long as the men don’t sink above the fork,” said the commandant of one of them to me. And it is beside these swamps that the traders, for many short-lived generations past, have planted their “factories.”

The word “factory” points back to a time when the traders made the palm-oil themselves. The natives make nearly the whole of it now and bring it down the rivers in casks, but the “factories” keep their name, though they are now little more than depots of exchange and retail trade. Formerly they were made of the hulks of ships, anchored out in the rivers, and fitted up as houses and stores. A few of the hulks still remain, but of late years the traders have chosen the firmest piece of “beach” they could find, or else have created a “beach” by driving piles into the slime, and on these shaky and unwholesome platforms have erected dwelling-houses with big verandas, a series of sheds for the stores, and a large barn for the shop. Here the “agent” (or sometimes the owner of the business) spends his life, with one or two white assistants, a body of native “boys” as porters and boatmen, and usually a native woman, who in the end returns to her tribe and hands over her earnings in cash or goods to her chief.

The agent’s working-day lasts from sunrise to sunset, except for the two hours at noon consecrated to “chop” and tranquillity. In the evening, sometimes he gambles, sometimes he drinks, but, as a rule, he goes to bed. Most factories are isolated in the river or swamp, and they are pervaded by a loneliness that can be felt. The agent’s work is an exchange of goods, generally on a large scale. In return for casks of oil and bags of “kernels,” he supplies the natives with cotton cloth, spirits, gunpowder, and salt, or from his retail store he sells cheap clothing, looking-glasses, clocks, knives, lamps, tinned food, and all the furniture, ornaments, and pictures which, being too atrocious even for English suburbs and provincial towns, may roughly be described as Colonial.

From the French coasts, in spite of the free-trade agreement of 1898, the British trader is now almost entirely excluded. On the Ivory Coast, Dahomey, French Congo, and the other pieces of territory which connect the enormous African possessions of France with the sea, you will hardly find a British factory left, though in one or two cases the skill and perseverance of an agent may just keep an old firm going. In the German Cameroons, British houses still do rather more than half the trade, but their existence is continually threatened. In Portuguese Angola one or two British factories cling to their old ground in hopes that times may change. In the towns of the Lower Congo the British firms still keep open their stores and shops; but the well-known policy of the royal rubber merchant, who bears on his shield a severed hand sable, has killed all real trade above Stanley Pool. In spite of all protests and regulations about the “open door,” it is only in British territory that a British trader can count upon holding his own. It may be said that, considering the sort of stuff the British trader now sells, this is a matter of great indifference to the world. That may be so. But it is not a matter of indifference to the British trader, and, in reality, it is ultimately for his sake alone that our possessions in West Africa are held. Ultimately it is all a question of soap and candles.

We need not forget the growing trade in mahogany and the growing trade in cotton. We may take account of gold, ivory, gums, and kola, besides the minor trades in fruits, yams, red peppers, millet, and the beans and grains and leaves which make a native market so enlivening to a botanist. But, after all, palm-oil and kernels are the things that count, and palm-oil and kernels come to soap and candles in the end. It is because our dark and dirty little island needs such quantities of soap and candles that we have extended the blessings of European civilization to the Gold Coast and the Niger, and beside the lagoons of Lagos and the rivers of Calabar have placed our barracks, hospitals, mad-houses, and prisons. It is for this that district commissioners hold their courts of British justice and officials above suspicion improve the perspiring hour by adding up sums. For this the natives trim the forest into golf-links. For this devoted teachers instruct the Fantee boys and girls in the length of Irish rivers and the order of Napoleon’s campaigns. For this the director of public works dies at his drain and the officer at a palisade gets an iron slug in his stomach. For this the bugles of England blow at Sokoto, and the little plots of white crosses stand conspicuous at every clearing.

That is the ancestral British way of doing things. It is for the sake of the trade that the whole affair is ostensibly undertaken and carried on. Yet the officer and the official up on “The Hill” quietly ignore the trader at the foot, and are dimly conscious of very different aims. The trader’s very existence depends upon the skill and industry of the natives. Yet the trader quietly ignores the native, or speaks of him only as a lazy swine who ought to be enslaved as much as possible. And all the time the trader’s own government is administering a singularly equal justice, and has, within the last three years, declared slavery of every kind at an end forever.

In the midst of all such contradictions, what is to be the real relation of the white races to the black races? That is the ultimate problem of Africa. We need not think it has been settled by a century’s noble enthusiasm about the Rights of Man and Equality in the sight of God. Outside a very small and diminishing circle in England and America, phrases of that kind have lost their influence, and for the men who control the destinies of Africa they have no meaning whatever. Neither have they any meaning for the native. He knows perfectly well that the white people do not believe them.

The whole problem is still before us, as urgent and as uncertain as it has ever been. It is not solved. What seemed a solution is already obsolete. The problem will have to be worked through again from the start. Some of the factors have changed a little. Laws and regulations have been altered. New and respectable names have been invented. But the real issue has hardly changed at all. It has become a part of the world-wide issue of capital, but the question of African slavery still abides.

We may, of course, draw distinctions. The old-fashioned export of human beings as a reputable and staple industry, on a level with the export of palm-oil, has disappeared from the Coast. Its old headquarters were at Lagos; and scattered about that district and in Nigeria and up the Congo one can still see the remains of the old barracoons, where the slaves were herded for sale or shipment. In passing up the rivers you may suddenly come upon a large, square clearing. It is overgrown now, but the bush is not so high and thick as the surrounding forest, and palms take the place of the mangrove-trees. Sometimes a little Ju-ju house is built by the water’s edge, with fetiches inside; and perhaps the natives have placed it there with some dim sense of expiation. For the clearing is the site of an old barracoon, and misery has consecrated the soil. Such things leave a perpetual heritage of woe. The English and the Portuguese were the largest slave-traders upon the Coast, and it is their descendants who are still paying the heaviest penalty. But that ancient kind of slave-trade may for the present be set aside. The British gun-boats have made it so difficult and so unlucrative that slavery has been driven to take subtler forms, against which gun-boats have hitherto been powerless.

We may draw another distinction still. Quite different from the plantation slavery under European control, for the profit of European capitalists, is the domestic slavery that has always been practised among the natives themselves. Legally, this form of slavery was abolished in Nigeria by a proclamation of 1901, but it still exists in spite of the law, and is likely to exist for many years, even in British possessions. It is commonly spoken of as domestic slavery, but perhaps tribal slavery would be the better word. Or the slave might be compared to the serf of feudal times. He is nominally the property of the chief, and may be compelled to give rather more than half his days to work for the tribe. Even under the Nigerian enactment, he cannot leave his district without the chief’s consent, and he must continue to contribute something to the support of the family. But in most cases a slave may purchase his freedom if he wishes, and it frequently happens that a slave becomes a chief himself and holds slaves on his own account.

It is one of those instances in which law is ahead of public custom. Most of the existing domestic slaves do not wish for further freedom, for if their bond to the chief were destroyed, they would lose the protection of the tribe. They would be friendless and outcast, with no home, no claim, and no appeal. “Soon be head off,” said a native, in trying to explain the dangers of sudden freedom. At Calabar I came across a peculiar instance. Some Scottish missionaries had carefully trained up a native youth to work with them at a mission. They had taught him the height of Chimborazo, the cost of papering a room, leaving out the fireplace, and the other things which we call education because we can teach nothing else. They had even taught him the intricacies of Scottish theology. But just as he was ready primed for the ministry, an old native stepped in and said: “No; he is my slave. I beg to thank you for educating him so admirably. But he seems to me better suited for the government service than for the cure of souls. So he shall enter a government office and comfort my declining years with half his income.”

The elderly native had himself been educated by the mission, and that added a certain irony to his claim. When I told the acting governor of the case, he thought such a thing could not happen in these days, because the youth could have appealed to the district commissioner, and the old man’s claim would have been disallowed at law. That may be so; and yet I have not the least doubt that the account I received was true. Law was in advance of custom, that was all, and the people followed custom, as people always do.

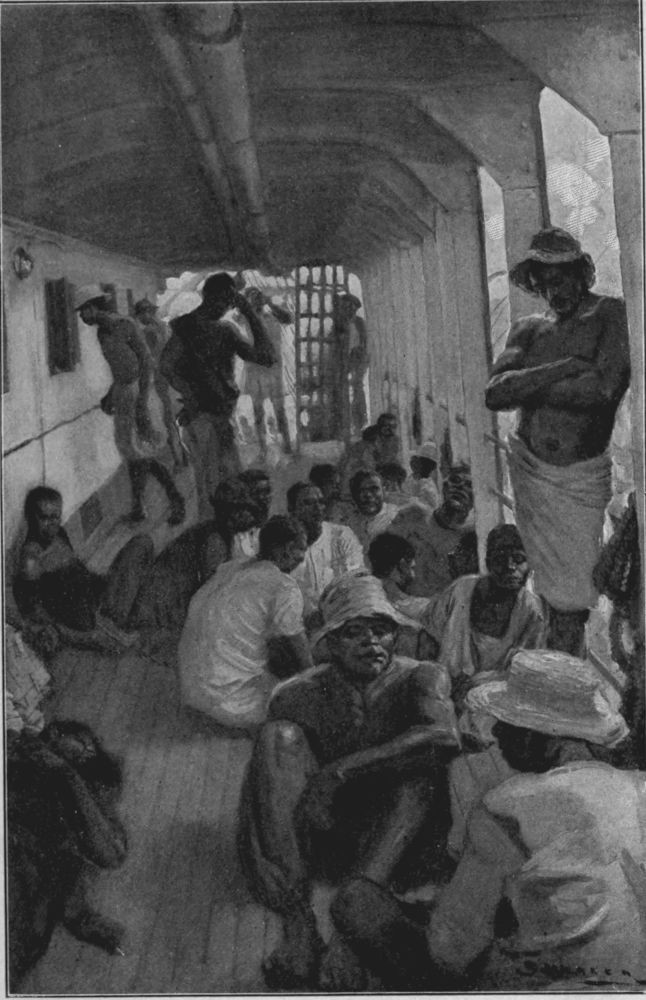

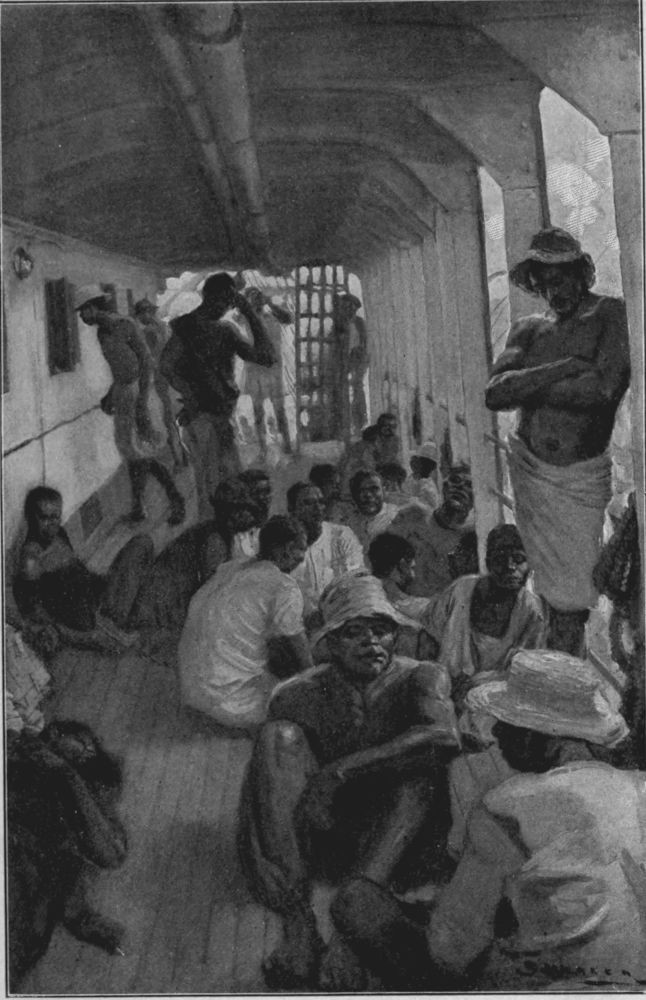

Even where there is no question of slave-ownership, the power of the chiefs is often despotic. If a chief covets a particularly nice canoe, he can purchase it by compelling his wives and children to work for the owner during so many days. Or take the familiar instance of the “Krooboys.” The Kroo coast is nominally part of Liberia, but as the Liberian government is only a fit subject for comic opera, the Kroo people remain about the freest and happiest in Africa. Their industry is to work the cargo of steamers that go down the Coast. They get a shilling a day and “chop,” and the only condition they make is to return to “we country” within a year at furthest. Before the steamer stops off the Coast and sounds her hooter the sea is covered with canoes. The captain sends word to the chief of the nearest village that he wants, say, fifty “boys.” After two or three hours of excited palaver on shore, the chief selects fifty boys, and they are sent on board under a headman. When they return, they give the chief a share of their earnings as a tribute for his care of the tribe and village in their absence. This is a kind of feudalism, but it has nothing to do with slavery, especially as there is a keen competition among the boys to serve. When a woman who has been hired as a white man’s concubine is compelled to surrender her earnings to the chief, we may call it a survival of tribal slavery, or of the patriarchal system, if you will. But when, as happens, for instance, in Mozambique, the agents of capitalists bribe the chiefs to force laborers to the Transvaal mines, whether they wish to go or not, we may disguise the truth as we like under talk about “the dignity of labor” and “the value of discipline,” but, as a matter of fact, we are on the downward slope to the new slavery. It is easy to see how one system may become merged into the other without any very obvious breach of native custom. But, nevertheless, the distinction is profound. As Mr. Morel has said in his admirable book on The Affairs of West Africa, between the domestic servitude of Nigeria and plantation slavery under European supervision there is all the difference in the world. The object of the present series of sketches is to show, by one particular instance, the method under which this plantation slavery is now being carried on, and the lengths to which it is likely to develop.

THE “KROOBOYS” WORKING A SHIP ALONG THE COAST

“In the region of the Unknown, Africa is the Absolute.” It was one of Victor Hugo’s prophetic sayings a few years before his death, when he was pointing out to France her road of empire. And in a certain sense the saying is still true. In spite of all the explorations, huntings, killings, and gospels, Africa remains the unknown land, and the nations of Europe have hardly touched the edge of its secrets. We still think of “black people” in lumps and blocks. We do not realize that each African has a personality as important to himself as each of us is in his own eyes. We do not even know why the mothers in some tribes paint their babies on certain days with stripes of red and black, or why an African thinks more of his mother than we think of lovers. If we ask for the hidden meaning of a Ju-ju, or of some slow and hypnotizing dance, the native’s eyes are at once covered with a film like a seal’s, and he gazes at us in silence. We know nothing of the ritual of scars or the significance of initiation. We profess to believe that external nature is symbolic and that the universe is full of spiritual force; but we cannot enter for a moment into the African mind, which really believes in the spiritual side of nature. We talk a good deal about our sense of humor, but more than any other races we despise the Africans, who alone out of all the world possess the same power of laughter as ourselves.

In the higher and spiritual sense, Victor Hugo’s saying remains true—“In the region of the Unknown, Africa is the Absolute.” But now for the first time in history the great continent lies open to Europe. Now for the first time men of science have traversed it from end to end and from side to side. And now for the first time the whole of it, except Abyssinia, is partitioned among the great white nations of the world. Within fifty years the greatest change in all African history has come. The white races possess the Dark Continent for their own, and what they are going to do with it is now one of the greatest problems before mankind. It is a small but very significant section of this problem which I shall hope to illustrate in my investigations.