II

PLANTATION SLAVERY ON THE MAINLAND

Loanda is much disquieted in mind. The town is really called St. Paul de Loanda, but it has dropped its Christian name, just as kings drop their surnames. Between Moorish Tangiers and Dutch Cape Town, it is the only place that looks like a town at all. It has about it what so few African places have—the feeling of history. We are aware of the centuries that lie behind its present form, and we feel in its ruinous quays the record of early Portuguese explorers and of the Dutch settlers.

In the mouldering little church of Our Lady of Salvation, beside the beach where native women wash, there exists the only work of art which this side of Africa can show. The church bears the date of 1664, but the work of art was perhaps ordered a few years before that, while the Dutch were holding the town, for it consists of a series of pictures in blue-and-white Dutch tiles, evidently representing scenes in Loanda’s history. In some cases the tiles have fallen down, and been stuck on again by natives in the same kind of chaos in which natives would rearrange the stars. But in one picture a gallant old ship is seen laboring in a tempest; in another a gallant young horseman in pursuit of a stag is leaping over a cliff into the sea; and in the third a thin square of Christian soldiers, in broad-brimmed hats, braided tail-coats, and silk stockings, is being attacked on every side by a black and unclad host of savages with bows and arrows. The Christians are ranged round two little cottages which must signify the fort of Loanda at the time. Two little cannons belch smoke and lay many black figures low. The soldiers are firing their muskets into the air, no doubt in the hope that the height of the trajectory will bring the bullets down in the neighborhood of the foe, though the opposing forces are hardly twenty yards apart. The natives in one place have caught hold of a priest and are about to exalt him to martyrdom, but I think none of the Christian soldiers have fallen. In defiance of the cannibal king, who bears a big sword and is twice the size of his followers, the Christian general grasps his standard in the middle of the square, and, as in the shipwreck and the hunting scene, Our Lady of Salvation watches serenely from the clouds, conscious of her power to save.

Unhappily there is no inscription, and we can only say that the scene represents some hard-won battle of long ago—some crisis in the miserable conflict of black and white. Since the days of those two cottages and a flag, Loanda has grown into a city that would hardly look out of place upon the Mediterranean shore. It has something now of the Mediterranean air, both in its beauty and its decay. In front of its low red and yellow cliffs a long spit of sand-bank forms a calm lagoon, at the entrance of which the biggest war-ships can lie. The sandy rock projecting into the lagoon is crowned by a Vauban fortress whose bastions and counter-scarps would have filled Uncle Toby’s heart with joy. They now defend the exiled prisoners from Portugal, but from the ancient embrasures a few old guns, some rusty, some polished with blacking, still puff their salutes to foreign men-of-war, or to new governors on their arrival. In blank-cartridge the Portuguese War Department shows no economy. If only ball-cartridge were as cheap, the mind of Loanda would be less disquieted.

There is an upper and a lower town. From the fortress the cliff, though it crumbles down in the centre, swings round in a wide arc to the cemetery, and on the cliff are built the governor’s palace, the bishop’s palace, a few ruined churches that once belonged to monastic orders, and the fine big hospital, an expensive present from a Portuguese queen. Over the flat space between the cliff and the lagoon the lower town has grown up, with a cathedral, custom-house, barracks, stores, and two restaurants. The natives live scattered about in houses and huts, but they have chiefly spread at random over the flat, high ground behind the cliff. As in a Turkish town, there is much ruin and plenty of space. Over wide intervals of ground you will find nothing but a broken wall and a century of rubbish. Many enterprises may be seen growing cold in death. There are gardens which were meant to be botanical. There is an observatory which may be scientific still, for the wind-gage spins. There is an immense cycle track which has delighted no cyclist, unless, indeed, the contractor cycles. There are bits of pavement that end both ways in sand. There is a ruin that was intended for a hotel. There is a public band which has played the same tunes in the same order three times a week since the childhood of the oldest white inhabitant. There is a technical school where no pupil ever went. There is a vast municipal building which has never received its windows, and whose tower serves as a monument to the last sixpence. There are oil-lamps which were made for gas, and there is one drain, fit to poison the multitudinous sea.

So the city lies, bankrupt and beautiful. She is beautiful because she is old, and because she built her roofs with tiles, before corrugated iron came to curse the world. And she is bankrupt for various reasons, which, as I said, are now disquieting her mind. First there is the war. Only last autumn a Portuguese expedition against a native tribe was cut to pieces down in the southern Mossamedes district, not far from the German frontier, where also a war is creeping along. No Lady of Salvation now helped the thin Christian square, and some three hundred whites and blacks were left there dead. So things stand. Victorious natives can hardly be allowed to triumph in victory over whites, but how can a bankrupt province carry on war? A new governor has arrived, and, as I write, everything is in doubt, except the lack of money. How are safety, honor, and the value of the milreis note to be equally maintained?

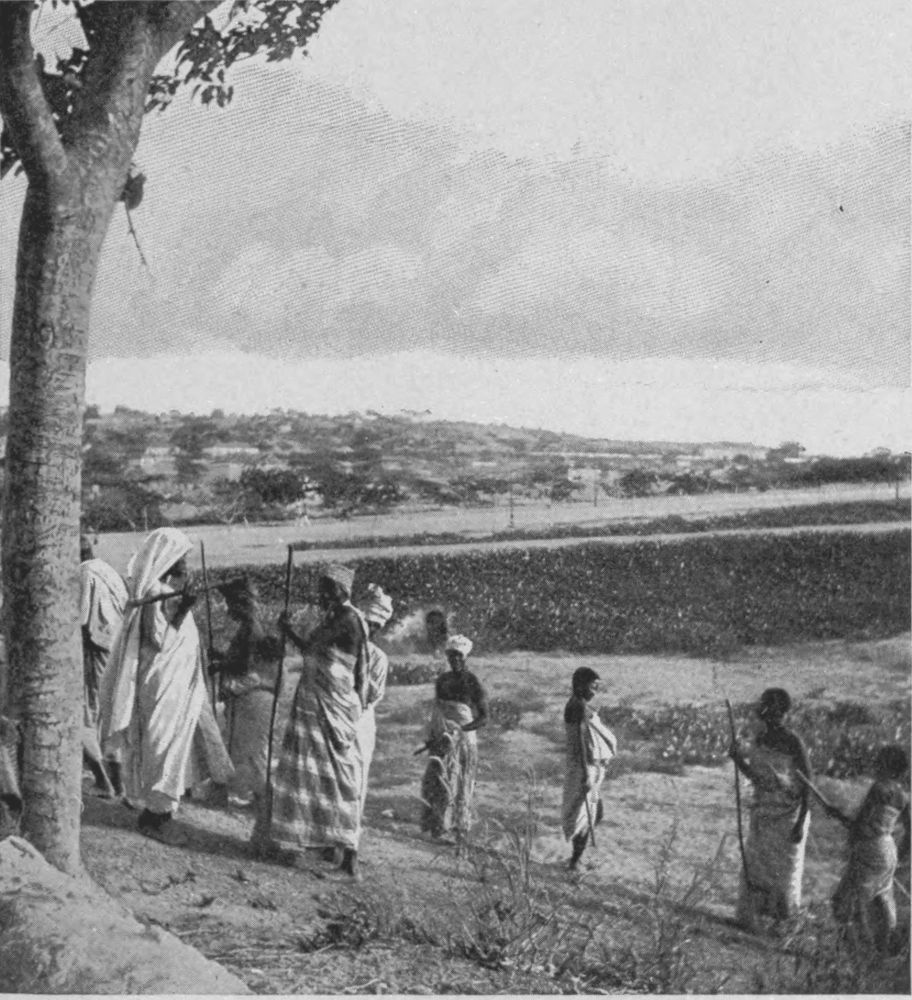

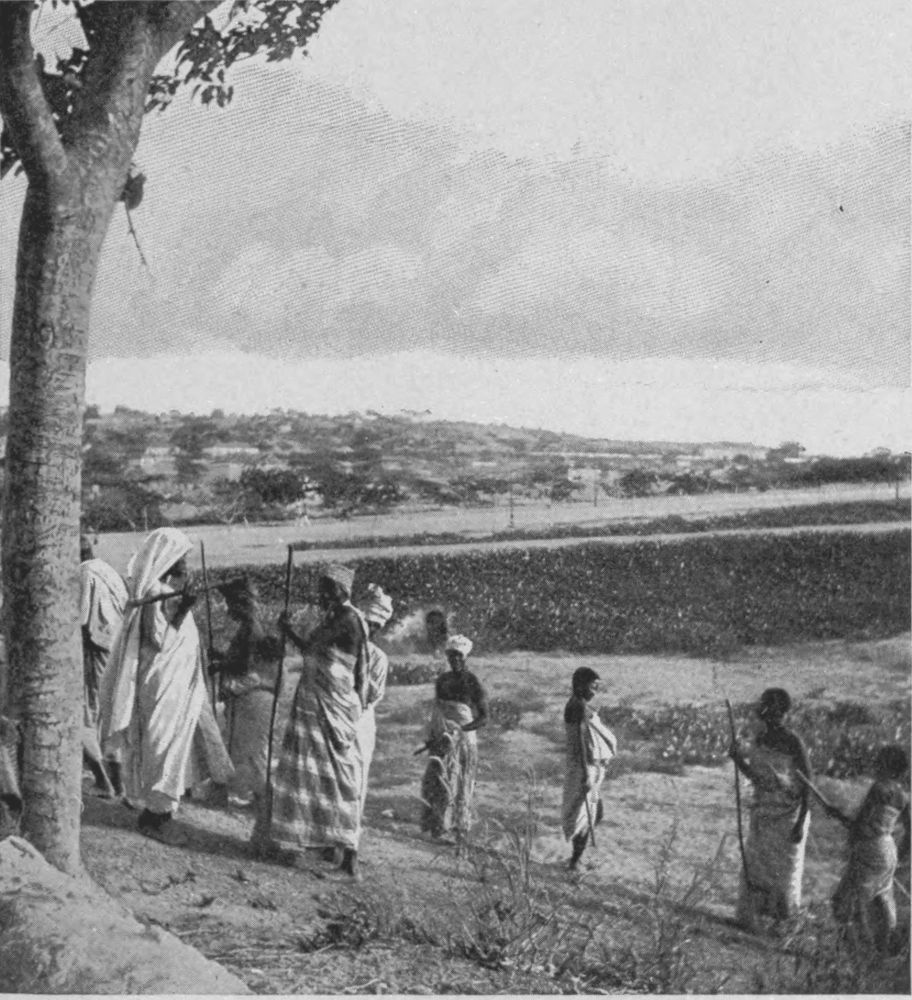

NATIVES IN CHARACTERISTIC DRESS

But there is an uneasy consciousness that the lack of money, the war itself, and other distresses are all connected with a much deeper question that keeps on reappearing in different forms. It is the question of “contract labor.” Cheap labor of some sort is essential, if the old colony is to be preserved. There was a time when there was plenty of labor and to spare—so much to spare that it was exported in profitable ship-loads to Havana and Brazil, while the bishop sat on the wharf and christened the slaves in batches. But, as I have said, that source of income was cut off by British gun-boats some fifty years ago, and is lost, perhaps forever. And in the mean time the home supply of labor has been lamentably diminished; for the native population, the natural cultivators of the country, have actually decreased in number, and other causes have contributed to raise their price above the limit of “economic value.”

Their numbers have decreased, because the whole country, always exposed to small-pox, has been suffering more and more from the diseases which alcoholism brings or leaves, and, like most of tropical Africa, it has been devastated within the last twenty or thirty years by this new plague to humanity, called “the sleeping-sickness.” Men of science are undecided still as to the cause. They are now inclined to connect it with the tsetse-fly, long known in parts of Africa as the destroyer of all domesticated animals, but hitherto supposed to be harmless to man, whether domesticated or wild. No one yet knows, and we can only describe its course from the observed cases. It begins with an unwillingness to work, an intense desire to sit down and do nothing, so that the lowest and most laborious native becomes quite aristocratic in his habits. The head then keeps nodding forward, and intervals of profound sleep supervene. Control over the expression of emotion is lost, so that the patient laughs or cries without cause. This has been a very marked symptom among the children I have seen. In some the great tears kept pouring down; others could not stop laughing. The muscles twitch of themselves, and the glands at the back of the neck swell up. Then the appetite fails, and in the cases I have seen there is extreme wasting, as from famine. Sometimes, however, the body swells all over, and the natives call this kind “the Baobab,” from the name of the enormous and disproportioned tree which abounds here, and always looks as if it suffered from elephantiasis, like so many of the natives themselves. Often there is an intense desire to smoke, but when the pipe is lit the patient drops it with indifference. Then come fits of bitter cold, and during these fits patients have been known to fall into the fire and allow themselves to be burned to death. Towards the end, violent trembling comes on, followed by delirium and an unconsciousness which may continue for about the final fortnight. The disease lasts from six to eight months; sometimes a patient lives a year. But hitherto there has been no authenticated instance of recovery. Of all diseases, it is perhaps the only one which up to now counts its dead by cent per cent. It attacks all ages between five years and forty, and even those limits are not quite fixed. It so happens that most of the cases I have yet seen in the country have been children, but that may be accidental. For a long time it was thought that white people were exempt. But that is not so. They are apparently as liable to the sickness as the natives, and there are white patients suffering from it now in the Loanda hospital.

My reason for now dwelling upon the disease which has added a new terror to Africa is its effect upon the labor-supply. It is very capricious in its visitation. Sometimes it will cling to one side of a river and leave the other untouched. But when it appears it often sweeps the population off the face of the earth, and there are places in Angola which lately were large native towns, but are now going back to desert. So people are more than ever wanted to continue the cultivation of such land as has been cultivated, and, unhappily, it is now more than ever essential that the people should be cheap. The great days when fortunes were made in coffee, or when it was thought that cocoa would save the country, are over. Prices have sunk. Brazil has driven out Angola coffee. San Thomé has driven out the cocoa. The Congo is driving out the rubber, and the sugar-cane is grown only for the rum that natives drink—not a profitable industry from the point of view of national economics. Many of the old plantations have come to grief. Some have been amalgamated into companies with borrowed capital. Some have been sold for a song. None is prosperous; but people still think that if only “contract labor” were cheaper and more plentiful, prosperity would return. As it is, they see all the best labor draughted off to the rich island of San Thomé, never to return, and that is another reason why the mind of Loanda is much disquieted.

I do not mean that the anxiety about the “contract labor” is entirely a question of cash. The Portuguese are quite as sensitive and kindly as other people. Many do not like to think that the “serviçaes” or “contrahidos,” as they are called, are, in fact, hardly to be distinguished from the slaves of the cruel old times. Still more do not like to hear the most favored province of the Portuguese Empire described by foreigners as a slave state. There is a strong feeling about it in Portugal also, I believe, and here in Angola it is the chief subject of conversation and politics. The new governor is thought to be an “antislavery” man. A little newspaper appears occasionally in Loanda (A Defeza de Angola) in which the shame of the whole system is exposed, at all events with courage. The paper is not popular with the official or governing classes. No courageous newspaper ever can be; for the official person is born with a hatred of reform, because reform means trouble. But the paper is read none the less. There is a feeling about the question which I can only describe again as disquiet. It is partly conscience, partly national reputation; partly also it is the knowledge that under the present system San Thomé gets all the advantage, and the mainland is being drained of laborers in order that the island’s cocoa may abound.

Legally the system is quite simple and looks innocent enough. Legally it is laid down that a native and a would-be employer come before a magistrate or other representative of the Curator-General of Angola, and enter into a free and voluntary contract for so much work in return for so much pay. By the wording of the contract the native declares that “he has come of his own free will to contract for his services under the terms and according to the forms required by the law of April 29, 1875, the general regulation of November 21, 1878, and the special clauses relating to this province.”

The form of contract continues:

- The laborer contracts and undertakes to render all such [domestic, agricultural, etc.] services as his employer may require.

- He binds himself to work nine hours on all days that are not sanctified by religion, with an interval of two hours for rest, and not to leave the service of the employer without permission, except in order to complain to the authorities.

- This contract to remain in force for five complete years.

- The employer binds himself to pay the monthly wages of ——, with food and clothing.

Then follow the magistrate’s approval of the contract, and the customary conclusion about “signed, sealed, and delivered in the presence of the following witnesses.” The law further lays it down that the contract may be renewed by the wish of both parties at the end of five years, that the magistrates should visit the various districts and see that the contracts are properly observed and renewed, and that all children born to the laborers, whether man or woman, during the time of his or her contract shall be absolutely free.

Legally, could any agreement look fairer and more innocent? Or could any government have better protected a subject population in the transition from recognized slavery to free labor? Even apart from the splendor of legal language, laws often seem divine. But let us see how the whole thing works out in human life.

An agent, whom for the sake of politeness we may call a labor merchant, goes wandering about among the natives in the interior—say seven or eight hundred miles from the coast. He comes to the chief of a tribe, or, I believe, more often, to a little group of chiefs, and, in return for so many grown men and women, he offers the chiefs so many smuggled rifles, guns, and cartridges, so many bales of calico, so many barrels of rum. The chiefs select suitable men and women, very often one of the tribe gives in his child to pay off an old debt, the bargain is concluded, and off the party goes. The labor merchant leads it away for some hundreds of miles, and then offers its members to employers as contracted laborers. As commission for his own services in the transaction, he may receive about fifteen or twenty pounds for a man or a woman, and about five pounds for a child. According to law, the laborer is then brought before a magistrate and duly signs the above contract with his or her new master. He signs, and the benevolent law is satisfied. But what does the native know or care about “freedom of contract” or “the general regulation of November 21, 1878”? What does he know about nine hours a day and two hours rest and the days sanctified by religion? Or what does it mean to him to be told that the contract terminates at the end of five years? He only knows that he has fallen into the hands of his enemies, that he is being given over into slavery to the white man, that if he runs away he will be beaten, and even if he could escape to his home, all those hundreds of miles across the mountains, he would probably be killed, and almost certainly be sold again. In what sense does such a man enter into a free contract for his labor? In what sense, except according to law, does his position differ from a slave’s? And the law does not count; it is only life that counts.

I do not wish at present to dwell further upon this original stage in the process of the new slave-trade, for I have not myself yet seen it at work. I only take my account from men who have lived long in the interior and whose word I can trust. I may be able to describe it more fully when I have been farther into the interior myself. But now I will pass to a stage in the system which I have seen with my own eyes—the plantation stage, in which the contract system is found in full working order.

For about a hundred miles inland from Loanda, the country is flattish and bare and dry, though there are occasional rivers and a sprinkling of trees. A coarse grass feeds a few cattle, but the chief product is the cassava, from which the natives knead a white food, something between rice and flour. As you go farther, the land grows like the “low veldt” in the Transvaal, and it has the same peculiar and unwholesome smell. By degrees it becomes more mountainous and the forest grows thick, so that the little railway seems to struggle with the undergrowth almost as much as with the inclines. That little railway is perhaps the only evidence of “progress” in the province after three or four centuries. It is paid for by Lisbon, but a train really does make the journey of about two hundred and fifty miles regularly in two days, resting the engine for the night. To reach a plantation you must get out on the route and make your way through the forest by one of those hardly perceptible “bush paths” which are the only roads. Along these paths, through flag-grasses ten feet high, through jungle that closes on both sides like two walls, up mountains covered with forest, and down valleys where the water is deep at this wet season, every bit of merchandise, stores, or luggage must be carried on the heads of natives, and every yard of the journey has to be covered on foot.

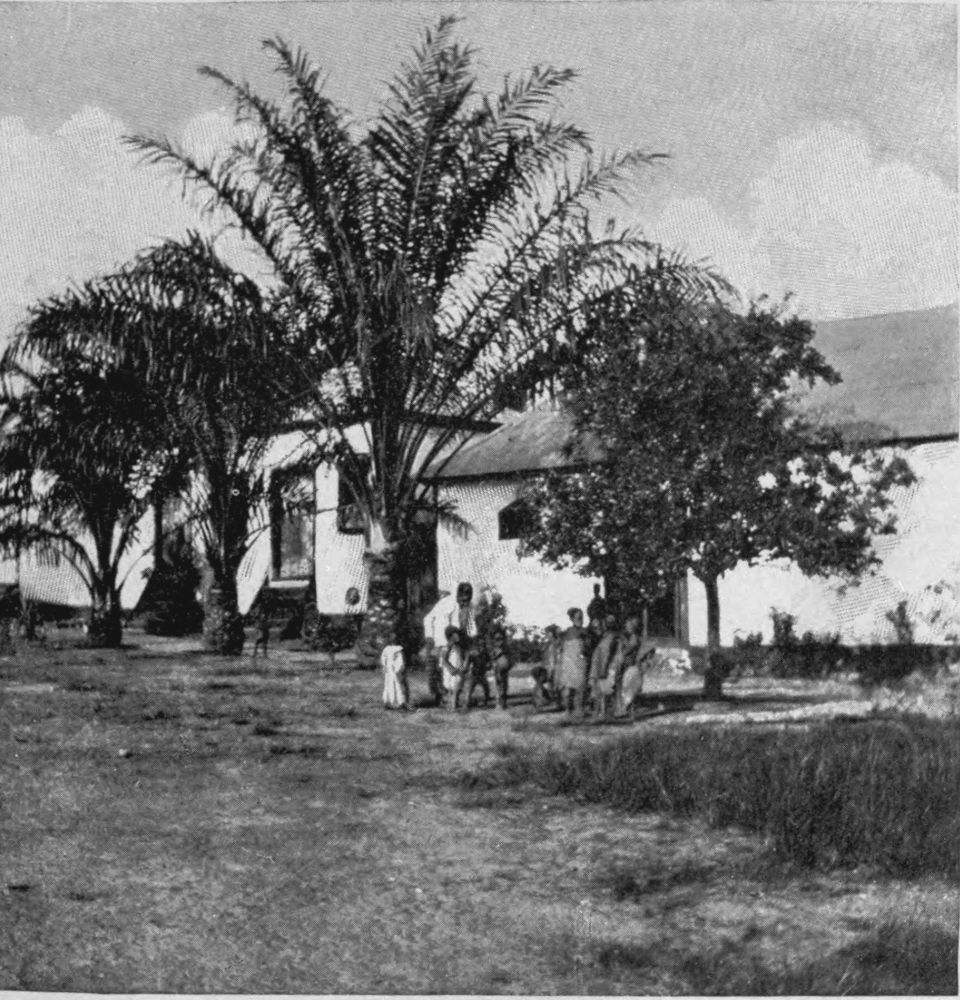

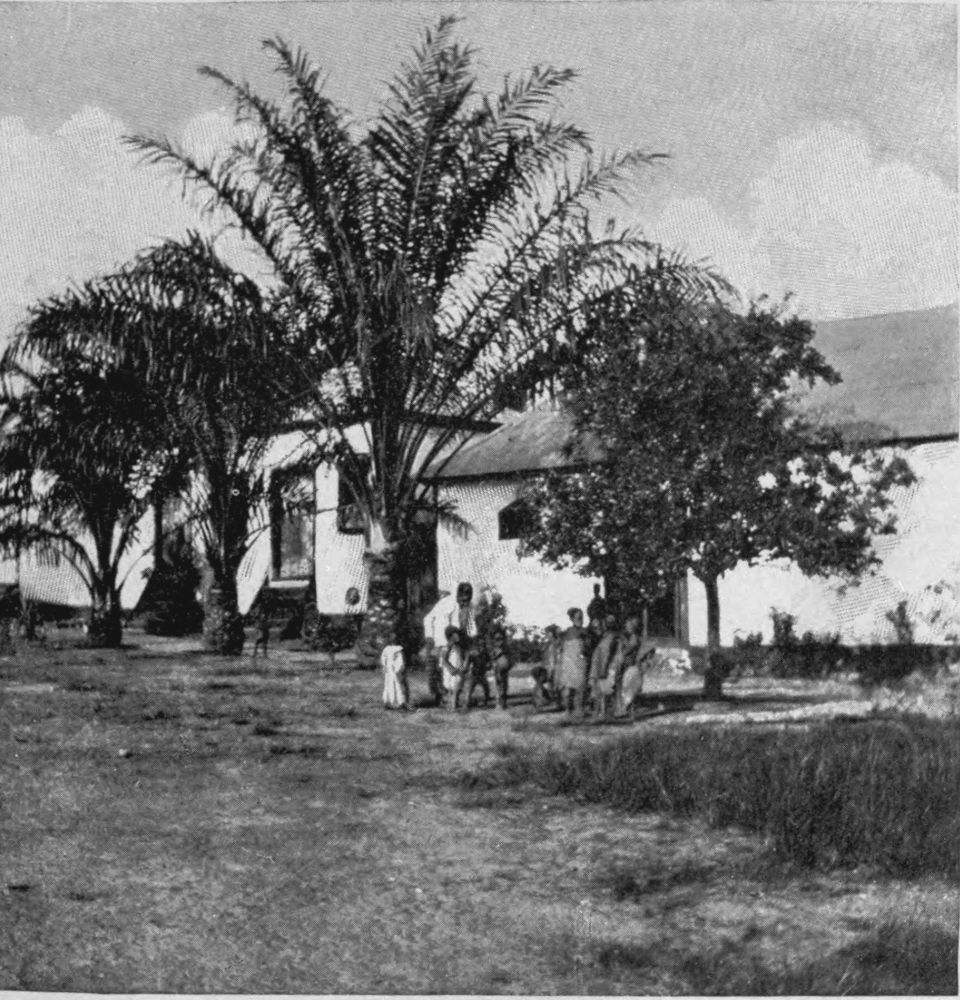

After struggling through the depths of the woods in this way for three or four hours, we climbed a higher ridge of mountain and emerged from the dense growth to open summits of rock and grass. Far away to the southeast a still higher mountain range was visible, and I remembered, with what writers call a momentary thrill, that from this quarter of the compass Livingstone himself had made his way through to Loanda on one of his greatest journeys. Below the mountain edge on which I stood lay the broad valley of the plantation, surrounded by other hills and depths of forest. The low white casa, with its great barns and outhouses, stood in the middle. Close by its side were the thatched mud huts of the work-people, the doors barred, the little streets all empty and silent, because the people were all at work, and the children that were too small to work and too big to be carried were herded together in another part of the yards. From the house, in almost every direction, the valleys of cultivated ground stretched out like fingers, their length depending on the shape of the ground and on the amount of water which could be turned over them by ditch-canals.

It was a plantation on which everything that will grow in this part of Africa was being tried at once. There were rows of coffee, rows of cocoa-plant, woods of bananas, fields of maize, groves of sugar-cane for rum. On each side of the paths mango-trees stood in avenues, or the tree which the parlors of Camden Town know as the India-rubber plant, though in fact it is no longer the chief source of African rubber. A few other plants and fruits were cultivated as well, but these were the main produce.

The cultivation was admirable. Any one who knows the fertile parts of Africa will agree that the great difficulty is not to make things grow, but to prevent other things from growing. The abundant growth chokes everything down. An African forest is one gigantic struggle for existence, and an African field becomes forest as soon as you take your eyes off it. But on the plantation the ground was kept clear and clean. The first glance told of the continuous and persistent labor that must be used. And as I was thinking of this and admiring the result, suddenly I came upon this continuous and persistent labor in the flesh.

It was a long line of men and women, extended at intervals of about a yard, like a company of infantry going into action. They were clearing a coffee-plantation. Bent double over the work, they advanced slowly across the ground, hoeing it up as they went. To the back of nearly every woman clung an infant, bound on by a breadth of cotton cloth, after the African fashion, while its legs straddled round the mother’s loins. Its head lay between her shoulders, and bumped helplessly against her back as she struck the hoe into the ground. Most of the infants were howling with discomfort and exhaustion, but there was no pause in the work. The line advanced persistently and in silence. The only interruption was when a loin-cloth had to be tightened up, or when one of the little girls who spend the day in fetching water passed along the line with her pitcher. When the people had drunk, they turned to the work again, and the only sound to be heard was the deep grunt or sigh as the hoe was brought heavily down into the mass of tangled grass and undergrowth between the rows of the coffee-plants.

Five or six yards behind the slowly advancing line, like the officers of a company under fire, stood the overseers, or gangers, or drivers of the party. They were white men, or three parts white, and were dressed in the traditional planter style of big hat, white shirt, and loose trousers. Each carried an eight-foot stick of hard wood, whitewood, pointed at the ends, and the look of those sticks quite explained the thoroughness and persistency of the work, as well as the silence, so unusual among the natives whether at work or play.

At six o’clock a big bell rang from the casa, and all stopped working instantly. They gathered up their hoes and matchets (large, heavy knives), put them into their baskets, balanced the baskets on their heads, and walked silently back to their little gathering of mud huts. The women unbarred the doors, put the tools away, kindled the bits of firewood they had gathered on the path from work, and made the family meal. Most of them had to go first to a large room in the casa where provisions are issued. Here two of the gangers preside over the two kinds of food which the plantation provides—flour and dried fish (a great speciality of Angola, known to British sailors as “stinkfish”). Each woman goes up in turn and presents a zinc disk to a ganger. The disk has a hole through it so that it may be carried on a string, and it is stamped with the words “Fazenda de Paciencia 30 Reis,” let us say, or “Paciencia Plantation 1½d.” The number of reis varies a little. It is sometimes forty-five, sometimes higher. In return for her disks, the woman receives so much flour by weight, or a slab of stinkfish, as the case may be. She puts them in her basket and goes back to cook. The man, meantime, has very likely gone to the shop next door and has exchanged his disk for a small glass of the white sugar-cane rum, which, besides women and occasional tobacco, is his only pleasure. But the shop, which is owned by the plantation and worked by one of the overseers, can supply cotton cloth, a few tinned meats, and other things if desired, also in exchange for the disks.

PLANTER’S HOUSE ON AN ANGOLA ESTATE

The casa and the mud huts are soon asleep. At half-past four the big bell clangs again. At five it clangs again. Men and women hurry out and range themselves in line before the casa, coughing horribly and shivering in the morning air. The head overseer calls the roll. They answer their queer names. The women tie their babies on to their backs again. They balance the hoe and matchet in the basket on their heads, and pad away in silence to the spot where the work was left off yesterday. At eleven the bell clangs again, and they come back to feed. At twelve it clangs again, and they go back to work. So day follows day without a break, except that on Sundays (“days sanctified by religion”) the people are allowed, in some plantations, to work little plots of ground which are nominally their own.

“No change, no pause, no hope.” That is the sum of plantation life. So the man or woman known as a “contract laborer” toils, till gradually or suddenly death comes, and the poor, worn-out body is put to rot. Out in the forest you come upon the little heap of red earth under which it lies. On the top of the heap is set the conical basket of woven grasses which was the symbol of its toil in life, and now forms its only monument. For a fortnight after death the comrades of the dead think that the spirit hovers uneasily about the familiar huts. They dance and drink rum to cheer themselves and it. When the fortnight is over, the spirit is dissolved into air, and all is just as though the slave had never been.

There is no need to be hypocritical or sentimental about it. The fate of the slave differs little from the fate of common humanity. Few men or women have opportunity for more than working, feeding, getting children, and death. If any one were to maintain that the plantation life is not in reality worse than the working-people’s life in most of our manufacturing towns, or in such districts as the Potteries, the Black Country, and the Isle of Dogs, he would have much to say. The same argument was the only one that counted in defence of the old slavery in the West Indies and the Southern States, and it will have to be seriously met again now that slavery is reappearing under other names. A man who has been bought for money is at least of value to his master. In return for work he gets his mud hut, his flour, his stinkfish, and his rum. The driver with his eight-foot stick is not so hideous a figure as the British overseer with his system of blackmail; and as for cultivation of the intellect and care of the soul, the less we talk about such things the better.

In this account I only mean to show that the difference between the “contract labor” of Angola, and the old-fashioned slavery of our grandfathers’ time is only a difference of legal terms. In life there is no difference at all. The men and women whom I have described as I saw them have all been bought from their enemies, their chiefs, or their parents; they have either been bought themselves or were the children of people who had been bought. The legal contract, if it had been made at all, had not been observed, either in its terms or its renewal. The so-called pay by the plantation tokens is not pay at all, but a form of the “truck” system at its very worst. So far from the children being free, they now form the chief labor supply of the plantation, for the demand for “serviçaes” in San Thomé has raised the price so high that the Angola plantations could not carry on at all without the little swarms of children that are continually growing up on the estates. Sometimes, as I have heard, two or three of the men escape, and hide in the crowd at Loanda or set up a little village far away in the forest. But the risk is great; they have no money and no friends. I have not heard of a runaway laborer being prosecuted for breach of contract. As a matter of fact, the fiction of the contract is hardly even considered. But when a large plantation was sold the other day, do you suppose the contract of each laborer was carefully examined, and the length of his future service taken into consideration? Not a bit of it. The laborers went in block with the estate. Men, women, and children, they were handed over to the new owners, and became their property just like the houses and trees.

Portuguese planters are not a bit worse than other men, but their position is perilous. The owner or agent lives in the big house with three or four white or whitey-brown overseers. They are remote from all equal society, and they live entirely free from any control or public opinion that they care about. Under their absolute and unquestioned power are men and women, boys and girls—let us say two hundred in all. We may even grant, if we will, that the Portuguese planters are far above the average of men. Still I say that if they were all Archbishops of Canterbury, it would not be safe for them to be intrusted with such powers as these over the bodies and souls of men and women.