CHAPTER 3

Freedom

A free man in a free country, that is the Greek ideal. The man enlightened and proud, relieved from ignorance, prejudgement and fear, is for the first time liable for his own life. Not only he participates actively and responsibly in the governing of his country, but most importantly he transforms the external coercion into inner freedom.

Every nation depending its intellectual level and maturity, gives a different interpretation to freedom. In the ancient world, ethnically free, were the Greeks, the Persians and the Egyptians, as long as they were not under foreign occupation. The Egyptians though and the Persians, according to the Greek ideal of freedom, could not be considered free citizens. They were bowing without question, without will and power before the commands of a deified king or an omnipotent, dogmatic religion, that had over life and death authority.

Greece objects to that Asian ideal and poses its own, that asks from the man to convert the outer duress into inner discipline. Respect and comply with the laws of the country, obey to the rulers, not because one is forced to or afraid of a punishment, but for the reason that an integral, responsible person with free spirit, makes the orders of the city commands of his own will. For all the great values to remain great, they have to be justified in the mind of a free man. As a free man there is no need to be afraid of anyone. Nobody stands higher, no authority, no person, no god. Greeks do not need to bend down before any ruler, they do not need to be obsequious and show flattery to please him. They realise, that as mortals, they might be powerless and weak towards the immortal gods. And yet they look their gods in the eyes, they do not kneel before them. Their sense of dignity as human beings does not allow that humiliation. Moreover, they firmly believe, that even for the gods themselves it would be degrading to witness such a demeaning behaviour.

Precisely that consists their ingenuity. In the position of a capricious, tyrannical monarch stands the Law, as the indisputable, dominant master, which establishes and guarantees the freedom. They realised, that freedom is the supreme good, which deserves the utmost sacrifice. Naturally, in order to come to this realisation a man needs to try it first. And the Greeks did try it, they did live freely, they did taste the benefits, the prosperity and the gratification of freedom. That’s why, they never ceased to defend it fiercely and give willingly their lives for it.

The Persians

After the fall of the Assyrian Empire in the 7th century B.c. the Medes were the uprising force in Mesopotamia. In 610 B.c. they conquered the northern Syria, in 585 B.c. they reached all the way to the western part of today’s Turkey fighting against the Lydian kingdom and then they headed north-east towards Armenia. In the Iranian plateau Ecbatana, a palace city with seven concentric walls of different colours and two battlements, one overlaid with silver and the other with gold according to Herodotus, was the stronghold of the Medes kings, that offered the supervision of the area around Zagros mountainous controlling the trade between east and west. From there king Astyages was ruling his empire and all the tribes of the Medians chiefs were submissive to him. But no empire lasts forever.

In the 7th century B.c. some people got settled in a region south, between the edge of Zagros mountain and the gulf, called Persia. In 559 B.c. a young man with endless ambition and limitless skills rose to the throne of Persia, Cyrus. In 553 B.c. Astyages decided, that Cyrus was extremely dangerous for his empire, so he marched against him. For three years they were fighting ferociously, till Cyrus suddenly won and captured Astyages. That was achieved due to a treason provoked by Arpagus, commander of the Median army, as the Medians tribe chiefs didn’t appreciate Astyages’ totalitarian ambitions. In the contrary Cyrus was a master in the art of war, familiar with the ancient cities and the terrain of the region, expert on the traditions of the past and a visionary of the Persians future. When he entered Ecbatana, he received the appropriate rewards for his tolerance, sharpness and grace. Kings before him exercising traditional rights over their defeated enemies had endorsed despicable cruelty. Thanks to his idiosyncrasy and his cunning plan Cyrus chose the tactic of mercy. As Medians and Persians were both nomads and closely related to each other, Cyrus did not get tempted to treat his compatriots as slaves. Even Astyages, instead of being skinned alive, eaten by wild beasts or executed by impalement, he was granted pension with regal honours.

The neighbours, as they were not taking the Persians very seriously yet, they started to wonder about the possibilities, that arose after the fall of Astyages. In 547 B.c. Croesus, the king of Lydia, challenged Cyrus. The Persians defying the heavy winter and the inconceivable distance from their borders, followed their king all the way to Croesus’ capital, Sardis. They conquered the city and captured Croesus, who was neither executed nor his mythical fortune was looted. The Lydians surprised by Cyrus’ magnanimity interpreted it as weakness and as soon as he left, they revolted. Cyrus perceived their actions as the ultimate treason and ungratefulness, thus he retaliated viciously. New troops with new orders were sent from Ecbatana and Arpagus, the most valuable of Cyrus’ assistants, was appointed as chief commander. He rose to the occasion with brutal effectiveness and after punishing the Lydians he advanced west to the Aegean Sea. There in a tempting prosperity, scattered in the coastline of Minor Asia, were lying the glorious cities of a people known to the Persians as the ‘Yaunas’ after the name ‘Ionians’. Extremely argumentative to confront him united, they were proved to be an easy prey. A black shadow covered the Greek cities of Ionia. The world seemed to be shrinking. Never before the velocity of one man reached that far.

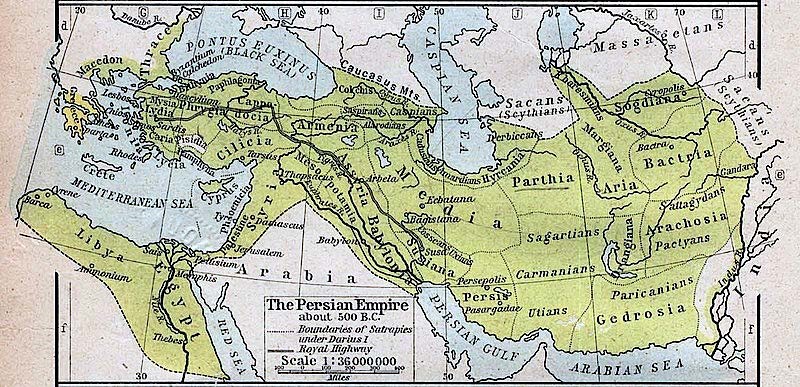

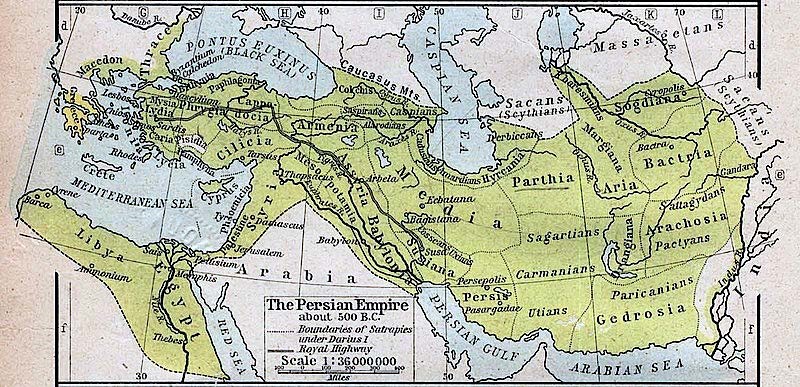

Persian Empire during the first dynasty ‘Achaemenids’ 6th cen. B.c. established by Cyrus and expanded by his sons. (common.wikimedia.org)

Cyrus himself continued east and conquered Gadara, Bactria, Arachosia and Sogdiana (parts of modern Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) securing the borders, where the empire was always vulnerable to incursions from the vast steppe areas of Central Asia. He stopped, when he finally came across a river, Iaxartes, that blocked his progression, and with seven cities demarcated his boundaries. In 540 B.c. he was prepared to proceed to his last venture. The ultimate target of every ambition conqueror, the ancient epicentre of the world. Leading a vast army, he invaded the fertile valleys of Mesopotamia pretending, that he was actually defending it as the personification of peace. That strategy proved to be very successful, since all the cities welcomed him with open gates, for they were aware, what their punishment would be, if they would have resisted. The empire expanded vastly and eventually comprised most of south west Asia, much of central Asia, parts of Europe and the Caucasus. From the Mediterranean Sea and Hellespont in the west to the Hindus River in the east, Cyrus created the largest empire the world had yet seen. He presented himself as the epitome of righteousness and justice, hence his absolute domination was a reward from the gods.

Cyrus died in the summer of 529 B.c. Perceptive as always, he had appointed his oldest son, Cambyses, as his successor and his youngest, Smerdis, commander of Bactria. The two brothers formed a strong and effective collaboration at first. Smerdis was watching over his brother’s back allowing him to march against the only great force, that had escaped the Persian fury, the most glorious one, Egypt. It took Cambyses four years to prepare for this enterprise. All the submissive nations were forced to contribute with taxes and soldiers. The victory was easy, Egypt was fallen, but it proved to be very difficult to control and impose taxes to the clergy. Cambyses managed ruthlessly to confiscate part of the priests’ colossal fortune, which no Pharaoh ever before had dared to do, causing their perpetual animosity. Not only the Egyptians considered him as a maniac oppressor, but now even the Persian chiefs saw a cruel tyrant in his face with catastrophic consequences. His strict rule, especially his stance on taxation and his long absence in Egypt was not on his benefit. A vague rumour of treason started to circulate.

The Persian aristocracy had a much better alternative, Smerdis, who was also son of Cyrus and additionally blessed with virtues admired in a king. Naturally a mutiny like that could not be concealed for long time. Therefore, beginning of 522 B.c. Cambyses decided to return to Persia and in March Smerdis claimed officially the throne. A very convenient accident solved this predicament. Cambyses got injured by his own sword and died within few days. Smerdis was the rightful heir and was appointed king of Persia. Cambyses death, an accident or not, was a very tempting idea for those, that were set aside by Smerdis. The high rank officers of the imperial army had returned from their adventure in Africa rugged and experienced. For example, Cambyses’ lancer, a distant cousin, Darius, of just twenty-eight years old, had access to the classified royal secrets and could evaluate Smerdis’ position, which was not as strong as it seemed. Smerdis came up with an impressive plan, to relieve for three years the submissive nations of paying taxes. In that case he had to find an alternative income source, his rivals, creating a split in the aristocracy. Many Persians regarded him as a disgrace and they started to contemplate his overthrow.

There were seven conspirators descending from noble families and Darius was one of them. They took Smerdis by surprise and killed him in his royal courts. Darius proved to be the greatest of all the Persian kings.

Relief of Darius in his throne, Persopolis (commons.wikimedia.org by Alisamii)

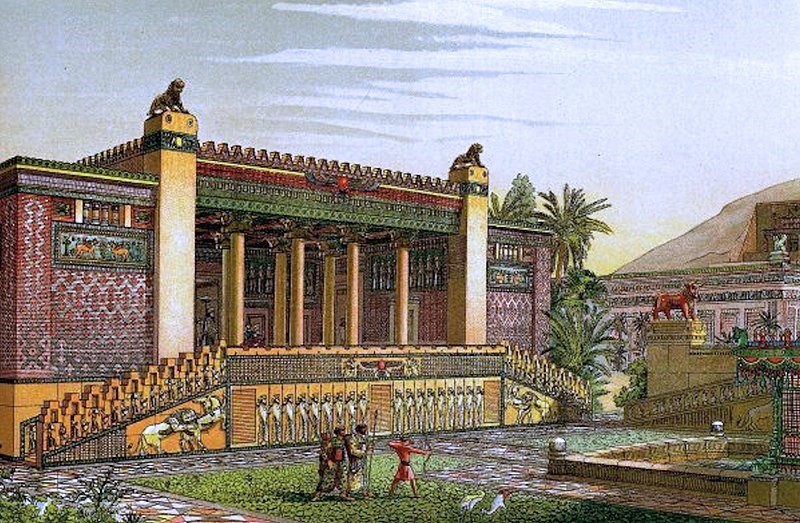

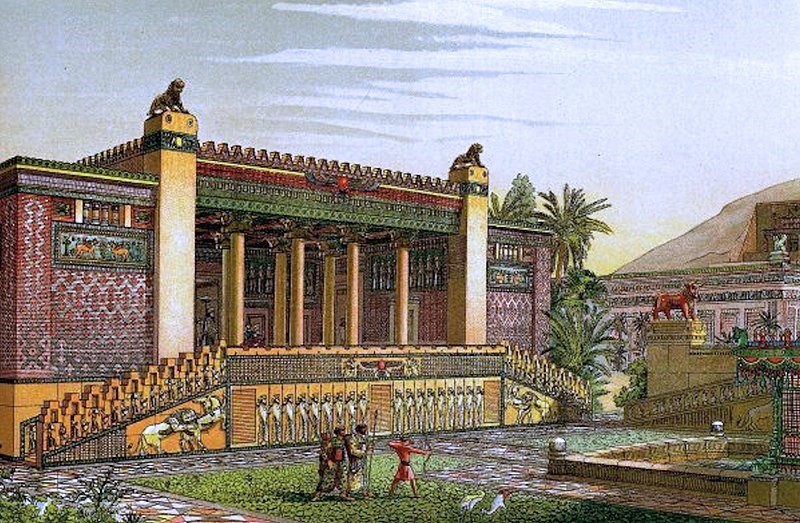

The early economy was based on herding, as the land was poor for agriculture. The sudden acquisition of the Media, Lydia, Babylon, Egypt and areas in India rich in gold made Persia an economic powerhouse controlling the fertile Mesopotamia, the grasslands of Anatolia, the trade routes in every direction and rich deposits of metals and other resources. Every year vast treasures were accumulated in the palaces, tribute demanded of the conquered vassals. Darius organised a new uniform monetary system introducing a universal currency, the daric. That was a major boost to international trade. Goods such as textiles, carpets, tools and metal objects began to travel throughout Asia, Europe and Africa. To further improve trade, Darius built a royal highway and expanded the network of roads and stations throughout the empire. Riders could make the entire journey of 2.500 km in a mere week. He divided his empire into districts known as Satrapies ruled by a governor living like a minor king in his own palace, accountable to the Great King. He also instituted a taxcollection system and established a complex postal system together with a network of spies he called the ‘Eyes and Ears of the King’. Darius also worked on construction projects throughout the empire, focusing on Susa, Pasargadae, Persepolis, Babylon and Egypt. Persepolis with its several royal palaces, the colossal throne room with possible capacity of 10.000 people and decorated with exquisite bas-reliefs, with its harem and a treasury was described by the ancient Greek historian Diodorus as the metropolis of the empire.

Reconstruction of the palace in Persepolis ‘Tachara’ by Charles Chipiez (commons.wikipedia.org)

Since its foundation by Cyrus, the Persian empire had been primarily a land empire with a strong army, but void of any actual naval forces. This was about to change. Darius is credited as the first king to invest in a Persian fleet. Darius was an adherent of Zoroastrianism, or at least a firm believer in Ahura Mazda. However, he allowed locals to keep their customs and religions. In many cuneiform inscriptions denoting his achievements, he presented himself as a devoted believer convinced, that he had a theistic right to rule over the world. As a regicide and an usurper, he had to legitimise his position and what better way, than to present himself as the chosen one directly from the god.

Darius did not at first gain general recognition, hence he had to impose his rule by force. The assassination of Smerdis was followed by widespread revolts in Egypt, Elam, Media, Parthia, Babylonia and Margiana, which threatened to disrupt the empire. In Margiana he showed excessive cruelty by killing fifty-five thousand rebels, in Babylonia he executed by impalement the leader of the revolt, Nebuchadnezzar II and in Media he cut off the ears, nose, tongue and removed the eyes of the leader, Phraortes. Having restored internal order in the empire, Darius undertook a number of campaigns for the purpose of strengthening his frontiers and checking the incursions of nomadic tribes. He attacked the Scythians east of the Caspian Sea and he conquered the Hindus Valley. Then he crossed the Danube river into European Scythia and he also invaded Thrace. Additionally, he conquered many cities of the northern Aegean and secured the submission of Macedonia. The empire had nearly 50 million subjects, approximately 44% of the total world’s population at that time.

Since the Ionian Greeks in Minor Asia had already yielded to Persian rule, they were forced to pay taxes and accept tyrannical regime. According to Herodotus, Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus, encouraged Artapherenes, Darius’ brother and satrap of Lydia, to take advantage of the appeal of Naxos’ aristocrats to supply them with troops, in order to regain control of their homeland. He convinced Artaphernes to attack Naxos and restore the exiles with the implication, that he would then seize power of the island, a unique prize in the path of every sea trade. Artaphernes agreed and promised 200 ships, but the expedition failed. Aristagoras’ political position was now at risk. In an attempt to save himself from the wrath of Persia and having literally nothing else to lose, he performed an acrobatic turnaround. He came out as an enthusiastic advocate of Democracy and planed a revolt with the Milesians and the other Ionians in 499 B.c. That was a clear declaration of war against the King of the Kings. There were no illusions about the magnitude of the challenge, they had to face. Nobody could defy and provoke a superpower like Persia without consequences. The punishment would be dreadful. To gain the support of the citizens, he deposed the tyrants in the other Ionian states and claimed he too would end his tyranny. Then he asked for help from the cities of the mainland. Only the Athenians and the Eretrians offered to assist to the revolution. Although it started out well, the tide soon turned in favour of the Persians. The cities fell one after the other and were once again brought under the rule of Persia. When Artaphernes conquered Miletus in 493 B.c., he raged against the city with vengeful mania. The men were slaughtered, the women were raped, the sons were emasculated and the daughters were enslaved. Because of its participation in this affair Darius swore vengeance on Athens and commanded a servant to repeat to him three times every day at dinner, “Master, remember the Athenians.”

The battle of Marathon

In Athens the aristocrats had always the tendency to passivity and compliance. They were not particularly in favour of the idea to risk the total demolition of their city instead of reaching a compromise with the mighty Persia, when Darius decided to march against Greece. Therefore, the democrats couldn’t trust the old elite, as they were sceptical about their patriotism. So, the elections of 493 B.c. were of a great importance. Themistocles was elected archon, one of the new generation politicians, who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian Democracy, the populist candidate, who was identified with the resolute, intractable battle. The Athenians committed themselves to fight and the Persian spies must have noted clearly their fierce intentions. The longer the punishment of Athens was delayed, the bigger the danger was to expand the terrorist cells all over Greece. For the good of the whole world and the future stability Aegean Sea had to be transformed into a Persian lake.

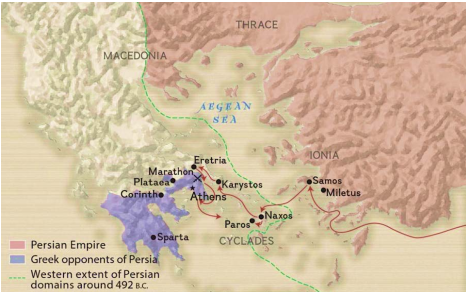

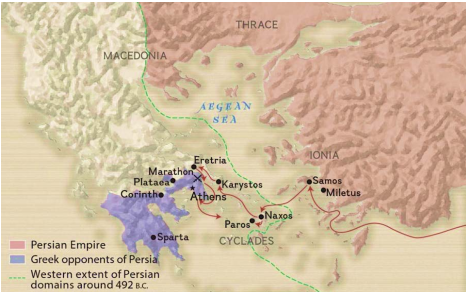

Darius sent in the spring of 492 B.c. new army and fleet to Thrace in order to move to the west, towards Macedonia and even further. Macedonia soon yielded to the inevitable and became part of the Persian empire. The year after heralds were sent south demanding earth and water for the king, which symbolises unconditional subordination. There were not many city-states, that refused. But two especially were unambiguously provoking. Athens, where not only the people refused to comply with the demands, but the heralds were put on trial and were sentenced to death and Sparta, where the heralds were thrown into a deep well to collect from there soil and water for their king.

(vk.com)

(vk.com)

In the summer of 490 B.c. the Persian forces attacked the Cyclades, destroyed Eretria and finally landed in Marathon

Finally beginning of 490 B.c. the numerous and well-equipped Persian army marched from Sousa towards Greece. The strategy was laid out by the Great King himself. They would cross Aegean Sea in order to convey to the islands the Persian domination and then they would eradicate Athens and Eretria. The total success was assertive. Overall command of the Persian army was in the hands of Datis, as Darius did not lead the invasion in person, and second-in-command was Artaphernes, Darius’ nephew. The total strength of the Persian army is unclear. It is estimated between 155.000 - 257.000 oarsmen and sailors, 50.000 - 100.000 soldiers and marines, 1.750 - 2.000 cavalry and 600 - 1.370 ships. The Persian fleet attacked Naxos to punish the island for the devastating expedition ten years before. The city and the temples were burnt to ashes, while the people were captured and drugged to the ships in chains. After Datis arranged a splendid performance of loyalty to the god Apollo in the sacred island of Delos, he advanced to the islands, accepting their surrender, taking hostages and recruiting young men by force. Nobody dared to resist. Mid-summer Datis reached Eretria. The siege started immediately and lasted for five days. The sixth day members of the aristocracy betrayed the city and opened its gates. Eretria was plundered and the population was enslaved on Darius’ orders. The road to Athens was free and paved by another traitor, Hippias, the son of the former tyrant, Peisistratos. With no feeling of remorse, he guided the Persians to the most ideal, protected bay, wide enough for their big fleet, with a suitable flat battlefield for the cavalry just 42 km away from Athens, Marathon.

The Athenians realised, the moment they feared for years had irreversibly arrived. Mythical rumours about the enormity of the Persian army were echoing over the city. No matter how many men were determined to protect their home, still the Persians were more, not to mention the overwhelming supremacy of their cavalry.

The hoplites, the heavily armed soldiers defending the young democracy, about 10.000 in total, marched to Marathon following the strategic plan of Miltiades, that was approved by the Athenians in their assembly. Miltiades, a politician and general, who had fought the Persians before during the Ionian revolt, was against those, who supported a defensive tactic from within the walls of Athens. On the contrary, he suggested to advance quickly to Marathon, block the two roads, that lead directly to the city, preventing the Persians from approaching Athens and fight then and there for their freedom.

At the same time Pheidippides, a ‘hemerodromos’, a day-long runner, was sent to Sparta to request assistance. He ran about 440 km in four days, but his epic effort was in vain. The Spartans declined his plead for help, as they were in the middle of ‘Carnea’ their biggest celebration, a sacred period of peace and truce. Devastated he went back to inform his co-citizens, that the Spartans could not show up earlier than in ten days. But the Athenians did not despair, as they had managed to secure the two roads, they acquired an exceptional defensive spot, plus a thousand men, the total manpower from the small city of Plataea had come selflessly to support them. That bold, heart-warming gesture was a tremendous encouragement for the Athenians. To hold on their position, stalling for a week till the help from Sparta arrives, was somewhat plausible.

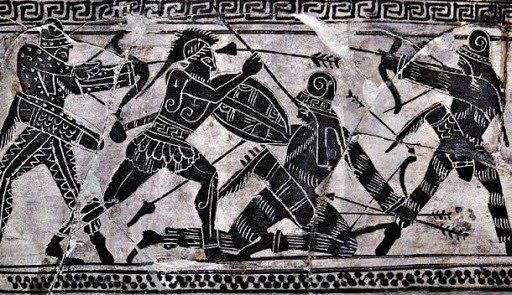

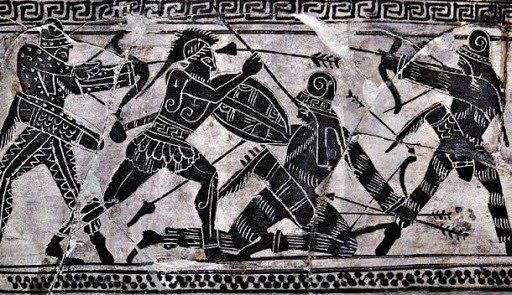

Scene of a battle, Greek Hoplites v/s Persian archers, black figure Lekythos 490 - 480 B.c. Athens (newspepper.gr)

Miltiades was confident, that the Persians were also taking under consideration the delay from Sparta due to the very good system of informants and spies they possessed. As the Athenians had blocked the roads to Athens, while their defences were not pierced yet nor compromised by treason or faction, there was only one way left to conquer Athens, before the Spartans appeared, by the sea. Three more days passed and nobody moved. Miltiades being aware of the Persian tactics in espionage had recruited his own private eyes amongst the enemy. That night they approached in secrecy the ten generals and the war archon to offer stunning news. The cavalry was gone! That was the moment Miltiades was anticipating. He begged the rest of the generals to engage the enemy in combat immediately, as the Persian force was divided. Either advance in the open valley and fight or hold the position and allow the cavalry to approach Athens from the sea and obliterate it. At least in the first option there was a slight possibility to win. Considering the advantage, that the terrain and size of their force gave to the Persians, plus their own lack in cavalry, archery and the significant shortcoming in infantry, half of the Greek generals hesitated. The decisive vote came from the chief archon, when he concurred with Miltiades. The dice was cast. With the first daylight they would take position to fight and face their biggest fear.

They stood assembled on the plain of Marathon, preparing to fight to the last man.

Behind them laid everything they held dear, their city, their homes, their families. The Athenians’ feelings are best expressed by Aeschylus, who fought himself in the Persian wars, when he states in his tragic play ‘The Persians’: “O, sons of the Hellenes! Fight for the freedom of your country! Fight for the freedom of your children and of your wives, for the gods of your fathers and for the sepulchres of your ancestors! All are now staked upon the strife!” The Greeks transformed into lethal machines made of bronze advanced towards the enemy, about 1.5 km away, attests Herodotus. The Persians prepared to meet them thinking it is suicidal madness for the Athenians to risk an assault with so small force and no support from either cavalry or archers.

The two opposing armies portrayed the two approaches of warfare, so distant from each other. The Persians preferred long range assault using archers followed up by a cavalry attack, whilst the Greeks favoured heavily armoured hoplites arranged in a densely packed formation called the phalanx. Each man carried a full gear of heavy bronze shield, spear and sword, thirty-five kilos of metal, wood and leather, and fought at close quarters. The Persians deployed a tactic of rapidly firing vast numbers of arrows into the enemy. Although it must have been an awesome sight, the lightness of the arrows made them pretty ineffective against the bronze armoured hoplites. At close quarters, the longer spears, the heavier swords, the better armour and the rigid discipline of the phalanx formation meant, that the Greek hoplites would have all of the advantages. The Persian infantry was evidently inadequately armoured, no match for hoplites.

The Athenians usually would arrange the phalanx in depth of eight ranks. Now Miltiades due to the fact, that the Greek army was outnumbered, ordered the centre of the formation to be arranged in the depth of four ranks, while the flanks in the depth of eight adjusting to the length of the Persian army to avoid getting bypassed. The best Persian and Sakai troops commanded from the centre, perhaps as many as ten men deep, while conscripts, pressed into service from tribute states, fought on the flanks. And he gave the order, Go! A united armed force of free men fighting for freedom. Only that can explain, how all those men dared to move against an admittedly invincible enemy. They marched forward at the usual pace, until they came at a bow shot. Then they would have to cover the final distance at speed or risk being slaughtered. It is beyond any imagination to have to race towards the enemy wearing this heavy gear in a summer day and be able to put up also a fight straight away. They passed through a hail of arrows launched by the Persian army, protected for the most part by their armour. Totally defying the reality around them, they just approached faster and faster till the phalanx finally collided with the enemy. The result was catastrophic. A barrier of bronze armoured men crushed their rivals, men very poorly protected and lightly armed. “In those first terrible seconds of collision, there was nothing but a pulverising crash of metal into flesh and bone” illustrates Tom Holland.

The Persian elite forces surged into the centre of the fray, easily gaining the ascendancy, pushing the weakened Greek centre back. It was a fatal mistake. The Greek wings quickly routed the inferior Persian levies on the flanks driving them back. The lines were broken and a total mayhem followed. The Greeks made another crucial decision. Instead of going after their fleeing foes, they turned inward to aid their co - warriors fighting in the centre of the battle enveloping the Persian centre, which broke in panic towards the ships pursued by the Greeks. Some, unaware of the local terrain, ran towards the swamps, where unknown numbers drowned. Fierce fighting continued in the shore. The Greeks captured seven ships of the enemy, but the rest of the fleet escaped with any Persians, who had managed to climb aboard.

Miltiades genius plan to incapacitate the enemy (knowitalltoknownothing.com)

Despite the pandemonium Datis maintained the control of his fleet, hence he posed a serious threat. The Athenian generals were deeply concerned, as to what had happened to the ships and the cavalry, that they had left, before even the battle began. And then from the mountain above them, they saw a reflection of light, a signal intended for the Persians. Athenians guessed it was treason. 42 km away their city stood defenceless. Driven by the fear to lose everything for the second time that day, covered in blood, exhausted, nearly paralysed, they had to run immediately back to Athens fully armed, to protect their families, their homes. In an astonishing demonstration of courage, resilience and determination they managed to reach their city as the first ships were approaching the port of Faliro, south of Athens. For few hours the Persian fleet remained anchored in the entrance of the bay watching the Greeks ready to fight. At sundown, seeing that the opportunity was lost, they turned east and sailed away into the night.

On the next day, the Spartan army arrived at Marathon, having covered the 220 km in only three days. They found themselves facing the greatest surprise. Admittedly the Athenians had won an admirable victory, so they treated them with an unprecedented respect. The Spartans assessed the battlefield at Marathon. For the first time they had the chance to observe and study the mythical Persians. They were not very impressive. Nothing compared to their unsurpassed military power.

Herodotus records that 6.400 Persian bodies were counted on the battlefield and it is unknown how many more perished in the swamps. The Athenians lost 192 men and the Plataeans 11. For those heroes only one honour was appropriate. For the first and last time in city’s chronicles they were buried in the place of their sacrifice. A big tomb covered their wounded bodies, while marble plaques cited their names in eternity with the inscription:

“Ἑλλήνων προµαχοῦντες Ἀθηναῖοι Μαραθῶνι χρυσοφόρων Μήδων ἐστόρεσαν δύναµιν”

“Fighting at the forefront of the Greeks, the Athenians at Marathon laid low the army of the gilded Medes.”

Defeat at Marathon would mean the complete defeat of Athens. They would be deprived of their homes, of their ancestral lands, their liberty and all the boys would be castrated. That was the punishment ordained by the Great King. The defeat at Marathon barely touched the vast resources of the Persian empire. For the Greeks however, it was a paramount victory. It was the first time they had triumphed over the Persians, proving that they were not untouchable. They showed once and for all, that resistance rather than submission and enslavement, was within reach. Herodotus states: “Freedom and equality are great motivations and so those, who living under the yoke of a despot were not better fighters than their neighbours, as soon as they were set free, they became the best. Because each and every one of them felt, that fighting for a free country meant actually fighting for himself and when he was committed to a task, he was willing to do see it through effectively”. The battle was a critical, decisive moment for the young Athenian democracy, since the following years saw the rise of the Classical Greek civilisation, during which the western culture was born. The Battle of Marathon is often seen as a pivotal moment in European history.

Darius though was determined to completely subjugate Greece, so he began raising a huge new army. However, in 486 B.c. the Egyptians revolted, indefinitely postpo