CHAPTER 4

Classical Epoch

The Classical period (479 - 323 B.c.) is known as the most impressive era of unprecedented political and cultural achievement, which bequeathed the western civilisation a colossal influence. During this time Athens became the intellectual capital of the ancient world, where new heights in philosophy, sciences, arts and literature were reached and amazing monuments to human potential were erected. The brilliance of the Classical Greek world, that was founded on the attainment of virtue, helped develop a specific mindset, where the importance of the individual and the rationalistic spirit were paramount. The thinkers of this era have since dominated thought for thousands of years and have remained relevant to our day. The teachings of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle amongst others have been used as reference point for countless western thinkers, Hippocrates became the ‘Father of modern medicine’, where the Hippocratic oath is still used today, the plays of Sophocles, Aeschylus, Euripides and Aristophanes are considered among the masterpieces of western culture still performed all over the world, the classically ideal body, as established in the 5th century B.c. has been the most constantly copied style in all the arts, etc. Western thought began with the Greeks, who first granted rational order to nature and to human society, and defined man, as an individual with the capacity to use his reason.

Doubtless the Greek perception of the world was progressively secularised, the Gods faded slowly and vanished in front of the humans’ accomplishments. The people from a previous semi-independent state appear now to assume responsibility for their lives. Everything changes meaning and style. Tragedy from deeply religious obtains slowly political connotation and comedy becomes a tool for political animadversion. History is born, where facts, instead of mythical bloodlines, are meticulously recorded, medicine, which is based on exploring the cause of the disease, rather than relying on questionable practices of sorcery and so many more. The ideal of the free man, that was entrenched in the archaic era, completed in the 5th century B.c. and the flower of the western civilisation burst into full bloom. Never before nor since has been witnessed an outpouring of cultural development on such a grandiose and far reaching scale. This is the age of human discovery and triumph, a remarkable age, which, as it remains quite unique in its combination of economic growth, political excellence, cultural accomplishment and longevity, proudly bears the name classical.

The cradle of Western Civilisation

The victorious encounter with the almighty Persian empire offered a great experience, the memory of would constitute an everlasting reason for pride for the future generations and a constant invocation in similar challenges. Fighting off the Persians, as well as the Carthaginians in Sicily, reinforced the self-confidence of the Greeks and at the same time their sense of belonging in a broader cultural community outside their city-states. More than that the victory of the Greek forces is hailed as pivotal point in the development of western civilisation. If the Persians had prevailed, all future achievements of Greece would not have transpired.

After the Persian Wars, Athens emerged as the most dominant political, economic and cultural force in the Greek world. Yet the threat of a Persian attack was valid. The Persian Empire was as large, powerful and rich, as it always had been. There were garrisons in Thrace, in Hellespont and in every capital of every satrap. Clearly its western façade was a bit damaged, but very few in that vast empire had realised that. In the worst-case scenario, they were informed, that the king of Sparta was killed in a battle and Athens was a city burned down by their master. The King of the kings might not contemplate any longer a master plan to conquer Europe and the rest of the world, however his forces didn’t stop fighting in the Aegean Sea. His pursuits were limited to maintain control over Minor Asia. Xerxes had to accept the harsh reality, that even the greatest empires suffer from over-expansion. Besides, back in the heart of his empire new rebellions were taking place.

The Athenians, due to their large navy, committed themselves to ensure the freedom of the Greek cities in the Aegean islands and on the coast of Minor Asia. They led a host of other Greek city-states some willingly, some unwillingly, in a defensive alliance out of necessity to present a unified front against the danger of another Persian invasion. Members of the so-called Delian League contributed either ships and crew to the League’s navy, or money, that was kept in a treasury on the island of Delos. The tributes collected by the allies helped Athens expand and build a formidable empire. The decades that followed, the Persians were pushed away from the Aegean Sea, Thrace and Hellespont, and the Athenians instigated Ionia and Caria to revolt. In 466 B.c. they vanquished yet again the enemy. The Athenian navy, led by Cimon, destroyed the Persian fleet off the south coast of Minor Asia and straight afterwards the army, terminating once and for all the possibility of a third Persian invasion. With control of the funds and a strong fleet, Athens gradually transformed the members of the League into subjects. No one could challenge its navy.

It was at this time, that the power of Athens was being felt throughout the Greek world. The Athenians forced city-states to join the Delian League against their will or refused to allow others to withdraw. They even stationed garrisons in city-states to keep the peace and to secure, that Athens would receive their support. By 454 B.c. the Athenian domination of the Delian League was crystal clear, as it became increasingly apparent, that this alliance was really a front for Athenian imperialism and the treasury was moved from the island of Delos to the Acropolis of Athens. Payments to the League now became payments to the treasury of Athens. Spartans, hesitant to get involved in affairs outside of Peloponnesus did not join the Delian League. Instead they led the Peloponnesian League, an alliance mostly from their region, that acted as a counterbalance against the perceived Athenian hegemony of Greece. Athens had developed into a major superpower and its culture was unchallenged. The feeling of excellence and supremacy, that was achieved, was evident in every aspect of life, that expressed an anthropocentric vision of the world and permeated every creation of the Greek spirit.

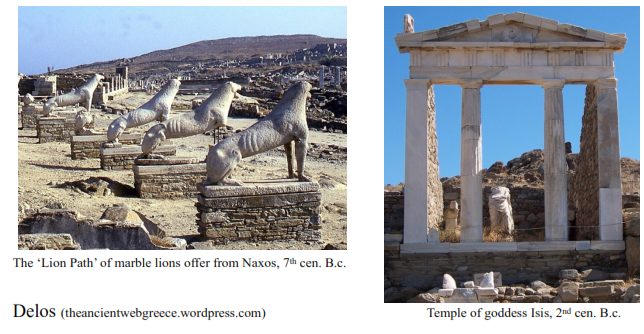

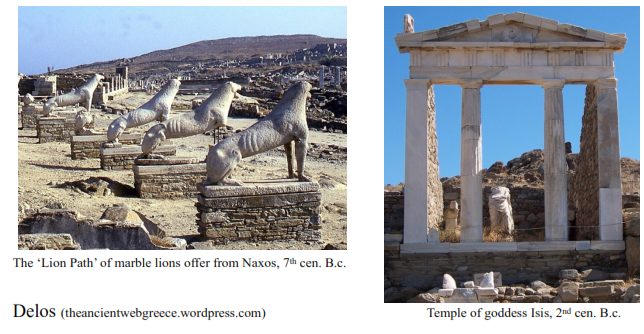

The island of Delos was the birthplace of the twin gods Apollo and Artemis and had Panhellenic religious significance. After the Persian wars it became the meeting centre of the Delian League and slowly developed into one of the most important harbours in the Aegean. Wealthy merchants, bankers and entrepreneurs start arriving from all over the Mediterranean, Greece, Italy, Egypt, Middle East and Minor Asia, especially after Delos was declared a free zone. They settled there with their families and built luxurious mansions, many surviving until this very day. The population reached almost 30.000 inhabitants. Temples, theatres, stadiums, gymnasiums, mosaics, etc. have been unearthed all over the island making Delos one of the most significant archaeological sites.

Philosophy

In the philosophical field it is witnessed a gradually shifting, that reflects a concern about the man rather than the cosmos, which crested with Socrates, Plato and Aristotle and began with Democritus (460 - 370 B.c.). After his death Democritus was portrayed as the ‘smiling philosopher’, apparently because he was ridiculing the absurdity of the mankind. His theory of atoms is considered to be one of the biggest accomplishments in philosophy. The brilliance and grandeur of his conception was revived during the scientific revolution in the 17th century. The radical ideas, that were accredited to Galileo, are in fact reformulations of Democritus’ beliefs. Aristotle regarded his suggestions as nonsense and put a great effort to prove so. The first Christians condemned the atomic theory and discouraged every study, because it tried to explain everything based on science and engineering, rather than the act of god, while at the same time it dismissed the concept of life after death. Everything consists of temporary formations of atoms, that at the end will vanish into chaos. Atomic theory was accused of impropriety and demoralisation. Especially, when it was praised in the poem of Lucretius, the roman poet and philosopher in the 1st cen. B.c. glorifier of the Greek philosopher, Epicurus, with which he wished to set the man free from prejudice, fear of death and the tyranny of the priests.

Democritus together with his mentor Leucippus, had the unique idea, that infinite, microscopic, solid atoms are wandering in a void space, till they collide and attach to each other creating everything in the universe, living and non-living. All movement and all change are due to ‘necessity’, an internal cause and not an agency operating from without. The force, that unites them, is the old Greek principal, the attraction of similars. Atoms with similar attributes, like shape, tend to coalesce. These atoms from the Greek word ‘atomo’, which means the one, that can not be divided into smaller pieces, are totally indestructible and invisible. They differ in size, shape, mass, position, and arrangement. Only, as long there were no traces of experiments nor tests to confirm this theory, it remained just a dogma, till physicists and chemists developed the necessary tools to prove it scientifically. However, modern atoms are different from Democritus’ atoms. They are not eternal, invincible nor invisible. They are even electrical charged and in the electromagnetic world similars do not attract but repel each other. More importantly they have been divided into smaller particles, hence they are not the fundamental elements of matter. That does not mean Democritus was wrong. It just denotes, that his elements were called ‘atoms’ rather hastily. Democritus’ atomic theory can not be discarded, unless there is evidence, that atoms, ‘indivisible basic elements’ do not exist. His progressive novelty is more evident, if we reflect upon his conception regarding the world as a whole and the position of the humans in it. He envisioned an infinite universe, where anything is possible. This world is just one of the numerous possibilities. Today physicists are recognising as mathematically probable, that the universe may in fact be a multiverse with other planets sustaining life.

Democritus also offered an analysis of the development of the human civilisation, a theory about happiness, a system of morals and ethics. The first humans had to fight to survive in a hostile environment. They learned to cooperate and to communicate in order to be more effective. They studied the animals for their own benefit and they picked up many useful tips. But the most remarkable charisma they possessed, intelligence, helped them understand, how the world works and learn from their experiences. That knowledge, which is acquired through the senses, is regarded as impure, while the one, which is obtained through logic and cognition, is referred to as authentic. When the senses are insufficient, there is a more adequate tool, Logic, the criteria, that evaluates and determines the truth. Once humans managed to cover their basic needs, they were able to evolve further and search for happiness. According to Democritus happiness comes from harmony and integrity. These same characteristics are important for a healthy society. Civilisation is indissolubly connected to the Greek city (‘πολιτισµός’ = the achievements of the human beings living in an organised city-state hence, ‘civil’-isation) and is a fragile human creation, which can easily slide to savagery. If harmony and control are disrupted, the stability of the city is in serious danger. Philosophy, art and happiness itself will soon perish. In order for the society to sustain prosperity, it should convey wisdom and proficient education to the young generation. The education of the children is a rigid responsibility. In addition, he advocated for moral virtue not because, that would please the gods and would ensure a satisfactory after life, but because, that consisted the only reliable path to happiness on earth. Anyway, the philosopher was certain, that humans only created gods to make sense of incomprehensible things around them. The universe, in his view, is a very comprehensible machine. Democritus launched the non-religious ethics, an anthropocentric morality, which sparked off Athens’ intellectual life and led to the humanistic sciences.

Socrates 469 - 399 B.c.

He is considered the father of western philosophy. Plato was his most famous student, who would teach Aristotle, who then became the tutor of Alexander the Great. Through Alexander’s conquests Greek philosophy was spread throughout the known world. Socrates’ greatest contribution to philosophy was to move intellectual pursuits away from the focus on physical science into the abstract realm of ethics and morality, as he firmly believed, that philosophy should achieve practical results for the greater good. The Roman philosopher Cicero portrayed it accurately, when he stated, “Socrates wrested philosophy from the heavens and brought it down to earth.”

He grew up during the golden age of Athens, served with distinction as a soldier, but became best known as a questioner of everything and everyone. Of humble descent, poor and dishevelled, he was never interested in what most people care for, fortune or a beautiful home. Absorbed in his own thoughts he was just too preoccupied to pay attention to simple things like clothes, food or money. Even so, he never claimed the characteristics of a conventionally successful life to be bad per se, neither motivated he others to follow his modesty. He never laboured to earn a living, but rather he embraced poverty and refused all his life to take money for what he offered. Running around the city of Athens in the agora and other public areas, like a horsefly, he would incessantly poke the people to stimulate and sharpen their mind. He believed, that education begets all the goods. And although the youths of the city kept following him, he insisted he was not a teacher. He was conversing with various people, young, old, male, female, slave and free, rich or poor, as long as he could persuade to join with him in a quest to analyse serious matters, such as the meaning of love, friendship, courage, justice, moderation etc.

No other great philosopher had such an obsession with the virtuous life than Socrates. Everyone should consider only one thing in life, if one acts fairly or not. His life is regarded paradigmatic of how anyone ought to live. In contrast to all religious saints he proposed an ethical system based on human reason, rather than theological doctrine. Socrates’s lifework consisted of the examination of people’s lives, including his own, because “the unexamined life is not worth living”. He felt morally obliged to try to convince his fellow citizens, that they shouldn’t care primarily for their bodies or their possessions, but how to improve their souls. The soul gets mutilated by unjust actions and gets benefited by the righteous ones. Wealth does not bring virtue, rather virtue brings all the benefits in life, for the individual and for the whole city. As long as the people would understand the virtues of life, valour, moderation, reverence, wisdom and justice, they would be on the right path to try to achieve them, in order to live a good, worthy life. The pursuit of truth, the perfection of the soul, the achievement of wisdom, that was his purpose. Socrates implemented a universal morality invoking the best interest of the individual, rather than altruism, which is usually the motivation of every moral behaviour. This extraordinary moral code does not rest upon a heavenly reward or the fear of punishment. The ultimate goal was the acquirement of an advanced knowledge regarding the paramount art of living well and he suggested, that human choices are ultimately motivated by the desire for happiness. Ergo, true wisdom comes essentially from knowing oneself. Aristotle often criticised Socrates, that he oversimplified human psychology, as he disregarded the irrational part of the character.

Faithful on his motto, “I know one thing, that I know nothing” he wouldn’t offer an opinion. When he was told, that the oracle of Delphi declared him the wisest man in Athens, Socrates baulked at first. Then he realised, that might be true, as actually he knew nothing, but at least he was aware of his ignorance. His style of teaching, immortalised as the Socratic Method, did not convey knowledge. Instead, with his questions, like an intellectual midwife, he would compel the audience to think through a problem to reach logical conclusions on, what is real, true and good. In these dialogues justifications were required, definitions on various subjects were clarified and assumptions were scrutinised. Anything, that seemed to withstand this examination, got temporarily accepted. Socrates inspired his followers to think for themselves instead of following the dictates of the society and the accepted superstitions concerning the gods or how one should behave. If one wants to shake the world, he should shake first oneself.

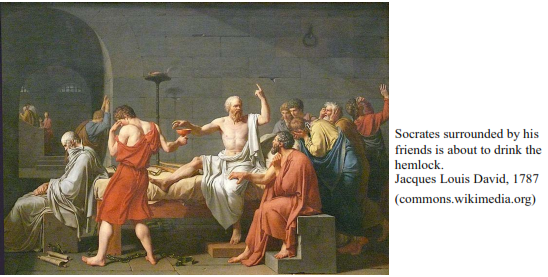

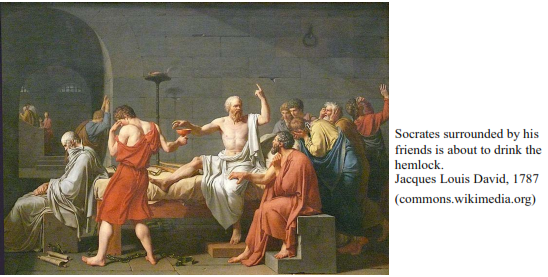

In refusing to conform to the social proprieties, Socrates angered many people in Athens, who accused him of breaking the law by violating these customs. During the last years of his life, Athens was in continual flux due to political upheaval. Although he had avoided political involvement and he didn’t align himself neither with oligarchs nor with democrats, he had friends and enemies among both, supporting and opposing to actions of both. When democracy was overthrown by a tyranny led by Plato’s relative, Critias, who had once been a student and friend of Socrates, he was put in the line of fire. In 399 B.c. He was indicted for failing to honour the Athenian gods and for corrupting the young. It has been suggested, that this charge was personally and politically motivated. Ignoring the advice of his friends and refusing the help of the gifted speech writer, Lysias, Socrates chose to defend himself in court. Instead of presenting himself as a good man, who had been wronged by a false accusation and plea for his life, as everybody would have expected, Socrates defied the Athenian court, proclaiming his role of Athens’ horsefly, a benefactor to all citizens, who kept them alert and aware. When it was time for Socrates to suggest an alternative punishment to death, which was called for by the prosecution, instead of proposing he be exiled, he advocated, that he should be honoured with free meals in the Prytaneum, a place reserved for heroes of the Olympic Games. This would have been considered a serious insult. The defiant tone of his defence contributed to the verdict. The jury was not amused and sentenced him to death by drinking a poisonous hemlock. Oddly, more members of the jury voted to give him the death sentence, than originally found him guilty. In other words, some, who thought he was innocent, still voted to have him executed.

Before Socrates’s execution, his friends offered to bribe the guards in order to rescue him. He declined, stating he wasn’t afraid of death. He lived all his life in Athens, the city he loved, so how could he be better off in exile. Most predominately, he was a loyal citizen of Athens, willing to abide by its laws, even the ones, that condemned him to death. Choosing not to flee, he spent his final days in the company of his friends. On his last day, Plato says, “he appeared happy in manner and words, as he died nobly and without fear’’. Condemned on the basis of his thought and teaching Socrates drank the hemlock without hesitation. Afterwards he walked around, until his legs grew numb and then he lay down, surrounded by his friends and waited for the poison to reach his heart.

He, himself, wrote nothing, so all that is known about him is filtered through the writings of his followers, most of all, his students Plato and Xenophon. Yet, his words and actions in the search for and defence of truth changed the world. He is one of the greatest examples of a man, who lived by his principles, even though ultimately, they cost him his life. His passion for definitions and challenging enquiries propelled the advancement of formal logic and systematic ethics from the time of Aristotle through the Renaissance and into the modern era.

Plato 428/427 B.c. - 348/347 B.c.

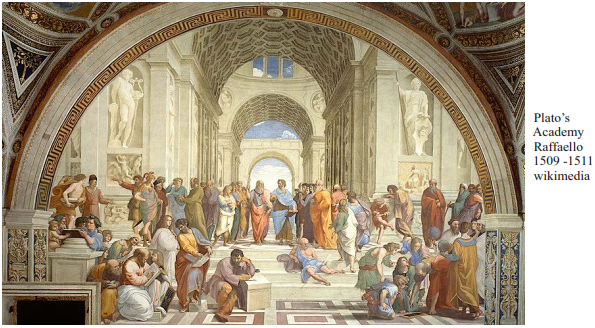

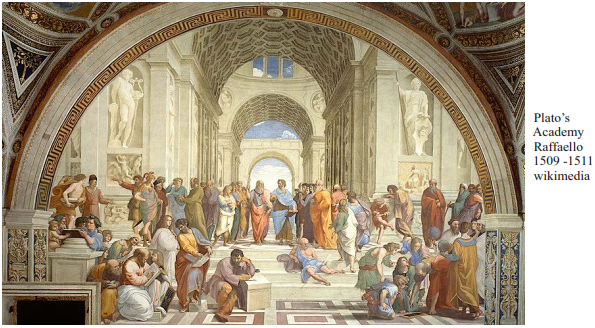

Plato came from one of the wealthiest and most politically active families in Athens. He was of noble Athenian lineage on both sides, his father Ariston died, when he was a child and his mother Perictione remarried. He was offered a good education, which included lessons in grammar, music, gymnastics and philosophy by some of the most prominent teachers of his time. Ancient sources present him as a bright yet modest boy, who excelled in his studies. His interests at first were focused more towards the arts, so he wrote plays and maybe even poetry. As his family was well connected, it was only expected of him to follow a political career. Soon though he got totally disappointed, as politics failed to live up to his expectations. When he heard Socrates talking in the market, he abandoned all his previous plans and devoted himself to philosophy. Plato was twenty-eight years old, when Socrates was executed. That had such a great impact on him, that he left Athens to travel Greece, Italy and Sicily, mostly to meet with other philosophers and mathematicians. When he returned to Athens, he founded the Academy around 387 B.c., the predecessor of the modern university. It was an influential centre of research and learning, that attracted many men of outstanding ability from throughout the Greek world. Over its years of operation, the Academy’s curriculum included astronomy, biology, mathematics, natural sciences, music, political theory and philosophy. Many intellectuals were schooled there, the most distinguished one being Aristotle. Plato died in Athens and was probably buried on the Academy grounds. Tradition holds, that the Academy endured for nearly 1.000 years as a beacon of higher knowledge. It was closed by the Christian Roman emperor Justinian in 529 in an effort to suppress the free Greek thought, as it was imposing a serious threat to the propagation of Christianity.

Plato twice in his life became involved with the politics of Syracuse. Dion, brotherin-law of the ruler Dionysius and one of Plato’s disciples, persuaded the young tyrant to invite Plato to come to help him become a philosopher-ruler, as described in his work ‘The Republic’. Although the philosopher was not entirely persuaded of this possibility, he agreed to go. At the end the tyrant turned against Plato, who almost faced death and instead he was sold into slavery. Thankfully a friend bought Plato’s freedom and sent him home. After Dionysius’s death, Dion asked Plato to return to Syracuse to tutor Dionysius II and guide him to become a philosopher king. Dionysius II seemed to accept Plato’s teachings, but he became suspicious of Dion, whom he expelled, and kept Plato against his will. Eventually he managed to leave Syracuse.

Plato is the innovator of the dialectic forms in philosophy. The use of dramatic elements, including humour, draws the reader in. Plato is unique in his ability to recreate the experience of conversation. The dialogues contain many authority figures and almost all feature Socrates as the main character. These characters convey particular lines of thought, while parallel inspire readers to join imaginatively in the discussion by proposing arguments and objections of their own. That form of expression, instead of systematic treatises, permitted him to develop the Socratic method of question and answer. In his dialogues, Plato discussed every kind of philosophical idea, including ethics regarding the nature of virtue, metaphysics about the man, the mind, immortality, political philosophy regarding the ideal state or censorship, epistemology, theology, cosmology, mathematics and the theory of art.

Plato’s dialogues aspire to find the Truth and determine, what is Good. He argued, there was one universal truth, which every human being had to recognise and strive to live in accordance with. This truth is embodied in the realm of Forms, a genuine, greater, cognitive place beyond space and time, where the ‘Forms’ or ‘Ideas’ are eternal, perpetual and incorruptible, while our world perceived by our senses is merely an inferior, inadequate, varying reflection. Plato’s Ideas are numerous. All the moral values constitute Ideas: virtue, justice, bravery, prudence etc. Mathematical concepts are also Ideas: equation, unity, point, line, as well as natural species, animals, plants, humans, water, fire etc. The Ideas are as many as the grammatical predicates and comprise the ultimate and self-existent ontological and conceptual centre, where reality and knowledge are established. They are the pure, constant archetypes of all the things, we see around us. When one describes a dog and a person as being good, the predicate good must have the same meaning regardless of the subjects, to which it is attributed. It draws its truth from the idea of good. These ideal, perfect, unchanging Forms are instantiated by many different particulars, which are essentially imperfect, perishable, material copies, that make up the world we comprehend.

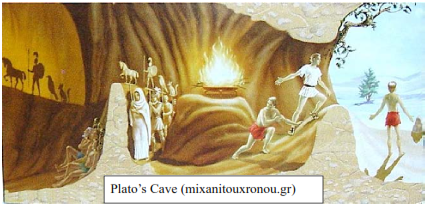

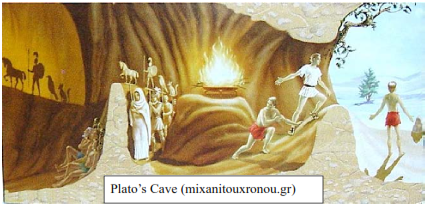

So, our world is divided. On one side there is the unclear, obscure reality of the everyday life, which all people are familiar with. On the other side there is the constant universe of the eternal Ideas, the existence of only few people suspect. The first originates in the world of the senses and the humans’ opinion, the second in the world of cognition and truth. The transition from one world to the other is the path of the philosophy. This theory was inimitably portrayed in Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’, from his work ‘The Republic’. The people in the cave are chained prisoners born and raised in a dark cave, with only a feeble light of fire behind them. They can perceive the outside world only by watching the vague shadows on the wall in front of them, thinking in their ignorance, it’s the reality. Not only they have never seen the real world, they don’t even suspect it exists. That sad situation is the humans’ condition. Plato imagined, what would occur, if some of the chained men were lucky enough to be released out into the world, to encounter the divine light of the sun and face the ‘true’ reality. Some people would immediately panic and retreat to the familiar darkness of the cave. The more enlightened would have the courage to look at the sun. When they would get accustomed to its blinding light and finally see the world, as it truly is, they would realise the deceit, in which they had lived. If they were then to return to the cave and try to explain, what they had seen, they would be ridiculed. Plato saw the outside world, which the humans from the cave glimpsed only for a second, as the timeless realm of Forms, where genuine reality resides. The shadows on the wall represent the world we see around us, which we assume to be real, but in fact is a mere imitation. According to Plato philosophy was not an aimless, theoretical rumination. On the contrary the philosopher has the duty to return to the cave to help the rest, that remain unenlightened. He developed his theory of Ideas to use it as a foundation, as a pedagogic basis, where his ideal society will be built on. In the classical era the question, how should one live to be worthwhile, formulated synchronously an ethical and a political discussion.

‘The Republic’ starts with a conversation between Socrates and some friends about justice, its essence and benefits for the righteous people. Thrasymachus stands out as he claims, that justice is nothing, but the interest of the powerful, advocating the blunt self-interest. If one can defy the rules and not get punished, that’s what one should do. The fair person anyway always ends up in a disadvantageous position compared to the unjust. Socrates in an attempt to substantiate his point of view suggests analysing the fair city, as he points out, it is easier to determine the meaning of justice in a bigger scale. Therefore, they examine the structure of an ideal, perfect state of justice, which they imagine for the sake of the conversation. In that state the humans are divided in three groups based on their innate intelligence and valour. The producers, which include all the farmers, labourers, merchants etc. responsible for the material support of the city, the protectors, the strong, brave armed forces liable for the city’s safety and the leaders, the intelligent, wise, rational ones, who are capable to govern and educate the rest. The last two constitute the guardians of the republic, who must be totally altruistic and generous, because many societies have failed, exactly, because their leaders were not virtuous. In this model justice is achieved, when each group is preoccupied with its own assignment and obligations, without seeking to interfere in the affairs of the others. That will lead to a harmonious, unprejudiced, pleased and therefore righteous society.

Plato continues by comparing his tripartite structure of the society with the soul, which also possesses three parts. The part of the desire, which corresponds to the producers and expresses the basic needs of the human being like food, drink and sex, the spirited, which corresponds to the protectors and is trying to bridle the desires, as is preoccupied with honour and competitive values and the logical part, which represents the leaders and to which the other two obey due to its superiority, as it is trying to reach truth and the good for the entire existence. The justice in a society coincides with the harmony in people’s soul. That gets accomplished, when they realise, each part of the soul has to fulfil its own purpose and reason has to be in control. Therefore, the essence of justice is not detected in external actions, but constitutes inner disposition of the subject collectively (city) as much as individually (soul), something like a healthy, beautiful, contend soul. Justice is so comprehensive, that a person, who possesses it, would also possess all the other virtues.

A large part of the dialogue then addresses, how the just state should be organised. Plato presented here his innovative ideas about collective ownership between the guardians to eliminate material