2. ATLANTIS, WHAT WAS PLATO REALLY UP TO?

To a storyteller like myself, Plato’s Atlantis reeks of fiction, and very good fiction at that.

Added to this is the fact that most of Plato’s philosophical works were cast as stories e.g., the Socratic Dialogues, as opposed to the more modern recitation of facts used by Aristotle, his contemporary.

Plato was essentially a philosopher who expressed his ideas through stories, and was very skilled at it. If we don’t understand this, we miss the boat.

OK here's the detail.

Alice Hickey, has a great deal to say about this storytelling aspect of Plato, whose Socratic Dialogues were stories designed not so much to reveal the character of Socrates—but the nature of truth, something much more illusive than the gadfly character of the real Socrates.

Of course, Plato could have been an artistic fool who had no idea how the real world operated, but all we know about him argues against that. What makes the satire even more complete is that Plato was actually given a chance to do that by one of the Greek kings and failed miserably. Perhaps he had a bit of street theater in him as well.

Plato’s artistic bent made him radically different from his pupil Aristotle, who could be said to represent our current logical, observational approach to knowledge. Plato was much more complex.

This is not to say that Plato didn’t observe nature, and wasn’t logical, but he was also skilled in using storytelling to arrive at a truth in a much different way.

I don’t know of any scholar who would dispute that Plato’s Atlantis story (of a once powerful country destroyed by the Gods because of corruption) wasn’t aimed directly at the declining character of the Athenians.

So we know what Plato was up to. He was constructing a story to illustrate a point: Athens couldn’t continue behaving in such an immoral way.

(The destruction and flooding of Mycenaean Crete by the monstrous c.1600 B.C. Santorini explosion would be a good example of such an oral tale).

My take is that it was the latter. After all, as Alice Hickey points out, that is exactly what any good storyteller would do. I highly suggest you read Alice Hickey on this storytelling aspect of Plato. It will open your eyes and perhaps help you look at his story of Atlantis in a much more complex way.

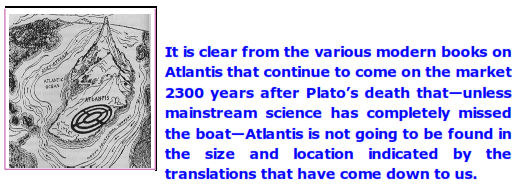

Sorry, but science is very good on matters like this. There is no evidence at all that a great landmass (equal in size to the United States) was once located in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

I suggest you read Part V of my book SOULSPEAK: The Outward Journey of the Soul on the nature and accuracy of oral transmission in preliterate cultures to see the ways in which stories were distorted and enlarged before you assume they could be passed down over a 7000 year period.

It just doesn’t happen. The Caribbean catastrophe story undoubtedly grew its own tale long before Plato got hold of it

They weren’t really interested in anything outside of the spiritual realm called Egypt.

It is far more likely that such a detailed description of Atlantis would have been maintained in some form by those

Mediterranean cultures (Egyptian,Mycenaean, Phoenecian) who were engaged in transatlantic/Mediterranean trading and whose sailors were, by nature, curious about everything.

(The exception to this curiosity may have been be the Phoenicians, who, it seems, had no interest in other cultures, only trading. They would leave their goods on the shore and then come back in several days to pick up what was offered in return.)

But this may not have been the case in the Caribbean, where it is clear that the trading was long term and highly sophisticated (cocaine and cotton being the desired raw materials). Relationships with the Mexican/Peruvian sources were surely developed to insure delivery and quality.

As sailors are by nature tale spinners, all Plato would have had to do was to go down to the docks of Piraeus and keep his ears open. So there was surely a rich source of raw catastrophe material.

A second, related question that begs to be answered is this: if

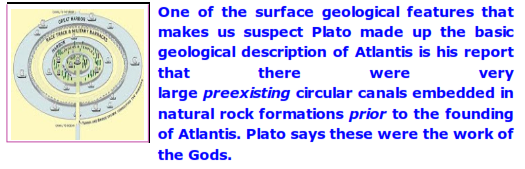

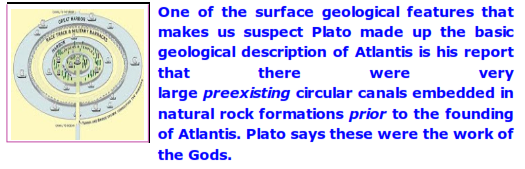

Outside of the size and impossible mid-Atlantic location—which Andrew Collins shows may have been due to a translation error that may have gone unnoticed for centuries, Plato's Atlantis has many geological oddities.

Digging canals is one thing, finding preexisting canals is another. For the resolution of this conundrum and several others (such as the extraordinary canal depths and widths) I suggest you read the amazing research of Ulf Richter.

Plato implies that this gift from the Gods of three very large stone canals encouraged the residents to rather easily dig (out of dirt) a secondary canal scheme that would lead to the ocean and other locations in Atlantis. There is nothing that can turn a suspicious reader completely around as to the accuracy and truth of a "tall tale" than a generous and expert sprinkling of known, accepted lore throughout the tale, and I believe this stone canal gambit is an excellent example of Plato's skill with such devices.

Although you may be thinking that Richter was able to identify a geologic site somewhere in the world similar to his final description of Atlantis, he wasn’t able to suggest any known place, sunken or otherwise, that fits.

So all we can again conclude is that Plato was indeed extremely skilled in stitching his geological description of Atlantis together from many sources.

Evidence of this can be seen in Richter's conclusion that Plato's geological description of Atlantis echoes that of other island/seaside/harbor/canal descriptions of preliterate seaports.

So that leaves us with one final question: is it possible that Plato's catastrophic tale (no matter how stitched up it became with bits and pieces of catastrophe lore) is actually based on a huge meteoric catastrophe that occurred in 9500 B.C. and that some of the stitched-in bits describing the destruction of an actual island empire are bits of that catastrophic lore?

The answer is unequivocally NO.

Oh, a huge catastrophe undoubtedly did occur in the Caribbean in 9500 B.C., that's not being questioned. Andrew Collins is pretty good on this.

What is being questioned is this: for such a detailed memory of a meteoric event in 9500 B.C. to have accurately maintained itself orally from 9500 B.C. until the first Mediterranean sailors hit the Caribbean in 2500 B.C. goes against everything we know about the accuracy of oral transmission in preliterate cultures. The inaccuracy inherent in oral transmission over great lengths of time (especially of historical dates) illustrates the Achilles heel of all Atlantis theories, namely the huge length of time between the event and Plato.

The date Plato gives of the destruction of Atlantis is approximately 9500 B.C.

That date is so distant from the time in which the earliest writing emerged (3200 B.C./hieroglyphics), that just entertaining the thought that historical information about the catastrophe could have been accurately maintained for 7000 years boggles the mind of anyone with any knowledge of how preliterate cultures actually maintain and preserve knowledge.

I have no doubt that oral tales would have abounded throughout the Caribbean from 9500 B.C. on, but those tales would have been so mangled by their transmission over that length of time that God knows what would have come through intact except some very basic facts and names (Atlaxxx, fire, destruction, sinking, flood).

Everything else is up for grabs. I say that as someone very familiar with preliterate oral transmission and traditions.

But that is still not the primary problem, which is this: how did any of these preliterate cultures record and keep track of the date of destruction so that they could hand it to the seafaring traders 7000 years later?

Sorry, it doesn't work that way. Preliterate people have a very simple way of describing the distant past. It's called " long, long ago."

Any hard date, like 9500 B C., is a very big stinky herring. Collins has no real answer for this, because there is none.

As fantastic as it seems, all we can really say is that Plato somehow made the date up (or we have misinterpreted the date that Plato gives) and that it happens to coincide with the date of the Caribbean meteoric catastrophe.

There is no other answer when it comes to the date except to suppose that somehow a literate shadow civilization existed over that 7000 year period and that it maintained the date of the catastrophe ( and details) until it was finally recorded by one of our known the literate civilizations.

I don't think so.

As for the rest of it, the bits and pieces, suffice it to say that Plato made up some of it them (like any good story teller) and the rest were delivered to him by some equally good maritime storytellers.

And we should never forget this fact: Plato made two lunges at the Atlantis myth ( Timaeus and Critias) and then broke off in the last elaboration and went on to something else.