( 11 )

BIG FOOD, MORE FOOD AND

THE NEW SCIENCE OF DIABESITY

FUELING THE INCREASE in eating opportunities was the desire of big food companies to make more money. They created an entirely new category of food, called “snack food,” and promoted it relentlessly. They advertised on TV, print, radio and Internet.

But there is an even more insidious form of advertising called sponsorship and research. Big Food sponsors many large nutritional organizations. And then there are the medical associations. In 1988, the American Heart Association decided that it would be a good idea to start accepting cash to put its Heart Check symbol on foods of otherwise dubious nutritional quality. The Center for Science in the Public Interest1 estimates that in 2002, the AHA received over $2 million from this program alone. Food companies paid $7500 for one to nine products, but there was a volume discount for more than twenty-five products! Exclusive deals were, of course, more expensive. In 2009, nutritional standouts such as Cocoa Puffs and Frosted Mini Wheats were still on the Heart Check list. The 2013 Dallas Heart Walk organized by the AHA featured Frito-Lay as a prominent sponsor. The Heart and Stroke Foundation in Canada was no better. As noted on Dr. Yoni Freedhoff’s blog,2 a bottle of grape juice proudly bearing the Health Check contained ten teaspoons of sugar. The fact that these foods were pure sugar seemed not to bother anybody.

Researchers and academic physicians, as key opinion leaders, were not to be ignored either. Many health professionals endorse the use of artificial meal-replacement shakes or bars, drugs and surgery as evidence-based diet aids. Forget about eating a whole, unrefined natural-foods diet. Forget about reducing added sugars and refined starches such as white bread. Consider the ingredient list of a popular meal-replacement shake. The first five ingredients are water, corn maltodextrin, sugar, milk protein concentrate and canola oil. This nauseating blend of water, sugar and canola oil does not really meet my definition of healthy.

In addition, impartiality—or the lack thereof—can be a serious issue when it comes to publishing medical and health information. The financial- disclosures section of some papers published in journals and on the web can run for more than half a page. Funding sources have enormous influence on study results.3 In a 2007 study that looked specifically at soft drinks, Dr. David Ludwig from Harvard University found that accepting funds from companies whose products are reviewed increased the likelihood of a favorable result by approximately 700 percent! This finding is echoed in the work of Marion Nestle, professor of nutrition and food studies at New York University. In 2001, she concluded that it is “difficult to find studies that did not come to conclusions favoring the sponsor’s commercial interest.”4

The fox, it seemed, was now guarding the hen house. Shills for Big Food had been allowed to infiltrate the hallowed halls of medicine. Push fructose? No problem. Push obesity drugs? No problem. Push artificial meal replacement shakes? No problem.

But the obesity epidemic couldn’t very well be ignored, and a culprit had to be found. “Calories” was the perfect scapegoat. Eat fewer calories, they said. But eat more of everything else. There is no company that sells “Calories,” nor is there a brand called “Calories.” There is no food called “Calories.” Nameless and faceless, calories were the ideal stooge. “Calories” could now take all the blame.

They say candy doesn’t make you fat. Calories make you fat. They say that 100 calories of cola is just as likely as 100 calories of broccoli to make you fat. They say that a calorie is a calorie. Don’t you know? But show me a single person that grew fat by eating too much steamed broccoli. I know it. You know it.

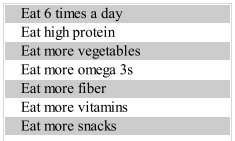

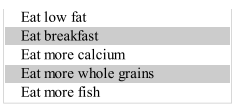

Furthermore, we cannot simply eat our usual diet and add some fat or protein or snacks and expect to lose weight. Against all common sense, weight-loss advice usually involves eating more. Just take a look at Table 11.1.

Table 11.1. Conventional advice for weight loss.

Why would anybody give such completely asinine advice? Because nobody makes any money when you eat less. If you take more supplements, the supplement companies make money. If you drink more milk, the dairy farmers make money. If you eat more breakfast, the breakfast-food companies make money. If you eat more snacks, the snack companies make money. The list goes on and on. One of the worst myths is that eating more frequently causes weight loss. Eat snacks to lose weight? It sounds pretty stupid. And it is.

SNACKING: IT WON’T MAKE YOU THIN

HEALTH PROFESSIONALS NOW heavily promote snacking, which previously had been heavily discouraged. But studies confirm that snacking means you eat more. Subjects given mandatory snacks 5 would consume slightly fewer calories at the subsequent meal, but not enough to offset the extra calories of the snack itself. This finding held true for both fatty and sugary snacks.

Increasing meal frequency does not result in weight loss.6 Your grandmother was right. Snacking will make you fat.

Diet quality also suffers substantially because snacks tend to be very highly processed. This fact mainly benefits Big Food, since selling processed instead of real foods yields a much larger profit. The need for convenience and shelf life lends itself to refined carbohydrates. After all, cookies and crackers are mostly sugar and flour—and they don’t spoil.

BREAKFAST: THE MOST IMPORTANT MEAL TO SKIP?

THE MAJORITY OF Americans identify breakfast as the most important meal of the day. Eating a hearty breakfast is considered a cornerstone of a healthy diet. Skipping it, we are told, will make us ravenously hungry and prone to overeat for the rest of the day. Although we think it’s a universal truth, it’s really only a North American custom. Many people in France (a famously skinny nation) drink coffee in the morning and skip breakfast. The French term for breakfast, petit déjeuner (little lunch) implicitly acknowledges that this meal should be kept small.

The National Weight Control Registry was established in 1994 and monitors people who have maintained a weight loss of 30 pounds (14 kilograms) for more than one year. The majority (78 percent) of the National Weight Control Registry participants eat breakfast.7 This, we are told, is proof that eating breakfast aids weight loss. But what percentage of those who did not lose weight ate breakfast? Without knowing, it’s impossible to draw any firm conclusions. What if 78 percent of those that did not lose weight also ate breakfast? This data is not available.

Furthermore, the National Weight Control Registry itself is a highly self- selected population8 and not representative of the general population. For example, 77 percent of registrants are women, 82 percent are college educated and 95 percent are Caucasian. Furthermore, an association (for instance, between weight loss and eating breakfast) does not mean causality. A 2013 systematic review 9 of breakfast eating found that most studies interpreted the available evidence in favor of their own bias. Authors who previously believed that breakfast protected against obesity interpreted the evidence as supportive. In fact, there are few controlled trials, and most of those show no protective effect from eating breakfast.

It is simply not necessary to eat the minute we wake up. We imagine the need to “fuel up” for the day ahead. However, our body has already done that automatically. Every morning, just before we wake up, a natural circadian rhythm jolts our bodies with a heady mix of growth hormone, cortisol, epinephrine and norepinephrine (adrenalin). This cocktail stimulates the liver to make new glucose, essentially giving us a shot of the good stuff to wake us up. This effect is called the dawn phenomenon, and it has been well described for decades.

Many people are not hungry in the morning. The natural cortisol and adrenalin released stimulates a mild flight-or-fight response, which activates the sympathetic nervous system. Our bodies are gearing up for action in the morning, not for eating. All these hormones release glucose into the blood for quick energy. We’re already gassed up and ready to go. There is simply no need to refuel with sugary cereals and bagels. Morning hunger is often a behavior learned over decades, starting in childhood.

The word breakfast literally means the meal that breaks our fast, which is the period when we are sleeping and therefore not eating. If we eat our first meal at 12 noon, then grilled salmon salad will be our “break fast” meal— and there’s nothing wrong with that.

A large breakfast is thought to reduce food intake throughout the rest of the day. However, such does not always seem to be the case.10 Studies show that lunch and dinner portions tend to stay constant, regardless of the amount of calories taken at breakfast. The more one eats at breakfast, the higher the total caloric intake over the entire day. Worse, taking breakfast increases the number of eating opportunities in a day. Breakfast eaters therefore tend to eat more and eat more often—a deadly combination.11

Furthermore, many people confess that they are not hungry first thing in the morning and force themselves to eat only because they feel that doing so is the healthy choice. As ridiculous as it sounds, many people force themselves to eat more in an effort to lose weight. In 2014, a sixteen-week randomized controlled trial of breakfast eating found that “contrary to widely espoused views this had no discernable effect on weight loss.”12

We are often told that skipping breakfast will shut down our metabolism.

The Bath Breakfast Project,13 a randomized controlled trial, found that “contrary to p