( 12 )

POVERTY

AND OBESITY

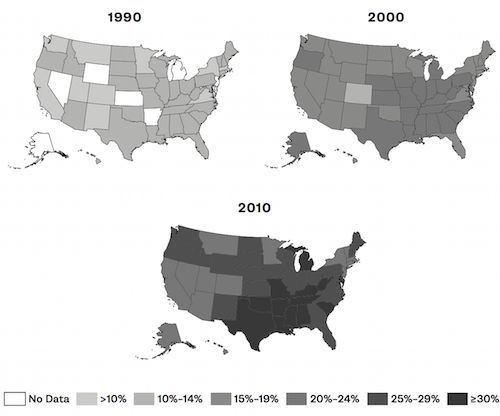

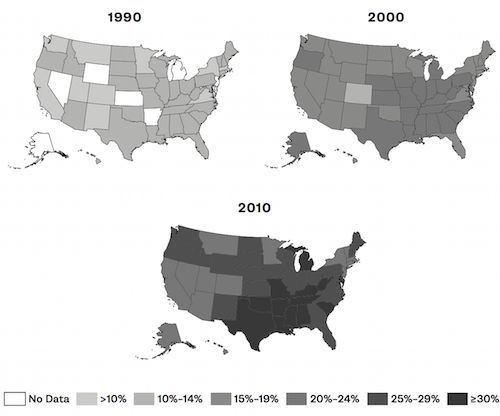

THE CENTER FOR Disease Control in Atlanta keeps detailed statistics about the prevalence of obesity in the United States, which varies strikingly between regions. It is also quite notable that those states with the least obesity in 2010 nonetheless have higher rates than those that were found in states with the most obesity in 1990. (See Figure 12.1.1)

Overall, there has been a huge increase in obesity in the United States.

Despite the similarity in culture and genetics between populations in Canada and the United States, U.S rates of obesity are much higher. This fact suggests that government policies must play a role in the development of obesity. Southern states such as Texas tend to have much more obesity than those in the west (California, Colorado) and north east.

Socioeconomic status has long been known to play a role in the development of obesity in that poverty correlates very closely with obesity. States with the most poverty tend to also have the most obesity. The southern states are relatively less affluent than those in the west and north east. With a 2013 median income of $39,031,2 Mississippi is the poorest state in the U.S. It also has the highest level of obesity, at 35.4 percent.3 But why is poverty linked to obesity?

Figure 12.1. Obesity trends among U.S. adults.

THEORIES, CALORIES AND THE PRICE OF BREAD

THERE IS A theory of obesity called the food-reward hypothesis, which postulates that the rewarding quality of the food causes overeating. Maybe obesity rates have increased because food is more enjoyable than it has ever been, causing people to eat more. Rewards reinforce behavior, and the behavior of eating is rewarded by the palatability—the deliciousness—of the food.

The increased palatability of food is not accidental. Societal changes have resulted in more meals being eaten away from the home, at restaurants and fast-food outlets. Many foods prepared in those venues may be specifically engineered to be hyper-palatable through the use of chemicals, additives and other artificial processes. The addition of sugar and seasonings such as monosodium glutamate (MSG) may trick the taste buds into believing that the food is more rewarding.

This argument is put forth in books such as Sugar, Salt and Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us,4 by Michael Moss, and The End of Overeating: Taking Control of the Insatiable American Appetite,5 by David Kessler.

Added sugars, salt and fat and their combination bear a disproportionate amount of blame for inducing us to overeat. But people have been eating salt, sugar and fat for the last 5000 years. These are not new additions to the human diet. Ice cream, a combination of sugar and fat, has been a summertime treat for more than 100 years. Chocolate bars, cookies, cakes and sweets existed long before the obesity epidemic in the 1970s. Children were enjoying their Oreo cookies in the 1950s without the problem of obesity.

The basic premise of this argument is that food is more delicious in 2010 than in 1970 because food scientists engineer it to be so. We cannot help but overeat calories and therefore become obese. The implication is that hyper- palatable “fake” foods are more delicious and more rewarding than real foods, but that seems very difficult to believe. Is a “fake,” highly processed food such as a TV dinner more delicious than fresh salmon sashimi dipped in soy sauce with wasabi? Or is Kraft Dinner, with its fake cheese sauce, really more enticing than a grilled rib-eye steak from a grass-fed cow?

But the association of obesity with poverty presents a problem. The food- reward hypothesis would predict that obesity should be more prevalent among the rich, since they can afford to buy more of the highly rewarding foods. But the exact opposite is true. Lower-income groups suffer more obesity. To be blunt, the rich can afford to buy food that is both rewarding and expensive, whereas the poor can afford only rewarding food that is cheaper. Steak and lobster are highly rewarding—and expensive—foods. Restaurant meals, which are expensive compared to home cooking, are also highly rewarding. Increased prosperity results in increased access to different types of highly rewarding food, which should result in more obesity. But it does not.

If this situation is not the result of diet, then perhaps the problem is lack of exercise. Perhaps the rich can afford to join gyms and therefore are more physically active, experiencing less obesity. In a similar vein, perhaps affluent children are more able to participate in organized sports, leading to less obesity. While these ideas may sound reasonable at first, further reflection reveals many discrepancies. The majority of exercise is free, often requiring no more than a basic shoe. Walking, running, soccer, basketball, push-ups, sit-ups and calisthenics all require minimal or no cost, and they are all excellent forms of exercise. Many occupations, such as construction or farming, involve significant physical exertion throughout the working day.

Those jobs require heavy lifting, day after day after day. Contrast that to an office-bound lawyer or a Wall Street investment banker. Spending up to twelve hours a day perched in front of a computer, his or her physical exertion is limited to walking from desk to elevator. Despite this large difference in daily physical activity, obesity rates are higher in the less affluent but more physically active group.

Neither food reward nor physical exertion can explain the association between obesity and poverty. So what drives obesity in the poor? It is the same thing that drives obesity everywhere else: refined carbohydrates.

For those dealing with poverty, food needs to be affordable. Some dietary fats are fairly inexpensive. However, we do not, as a general rule, drink a cup of vegetable oil for dinner. Furthermore, official government recommendations are to follow a low-fat diet. Dietary proteins, such as meat and dairy, tend to be relatively expensive. Less expensive vegetable proteins, such as tofu or legumes, are available but not typical in a North American diet.

This leaves carbohydrates. If refined carbohydrates are significantly cheaper than other sources of food, then those living in poverty will eat refined carbohydrates. Indeed, processed carbohydrates are entire orders of magnitude less expensive. An entire loaf of bread might cost $1.99. An entire package of pasta might cost $0.99. Compare that to cheese or steak, which might cost $10 or $20. Unrefined carbohydrates, such as fresh fruits and vegetables, cannot compare to the low, low prices of processed foods. A single pound of cherries, for instance, may cost $6.99.

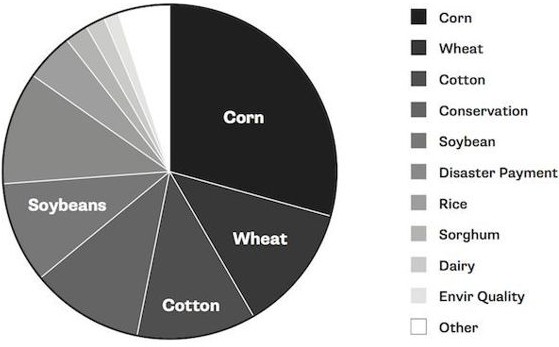

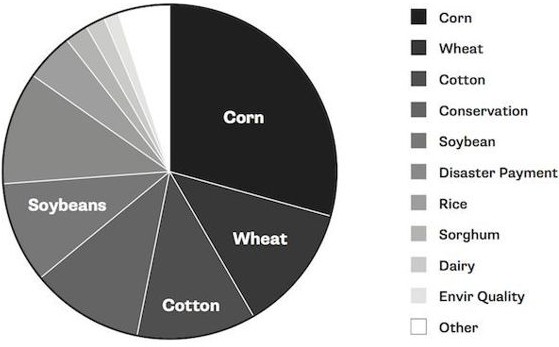

Why are highly refined carbohydrates so cheap? Why are unprocessed carbohydrates so much more expensive? The government lowers the cost of production with hefty agricultural subsidies. But not all foods get equal treatment. Figure 12.26 indicates which foods (and programs) receive the most in subsidies.

Figure 12.2. U.S. agricultural subsidies, 1995–2012.

In 2011, the United States Public Interest Research Groups noted that “corn receives an astounding 29 percent of all U.S. agricultural subsidies, and wheat receives a further 12 percent.” 7 Corn is processed into highly refined carbohydrates for consumption, including corn syrup, high-fructose corn syrup and cornstarch. Wheat is almost never consumed as a whole berry but further processed into flour and consumed in a wide variety of foods.

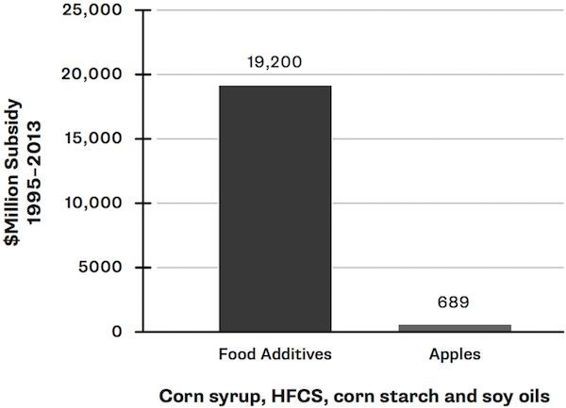

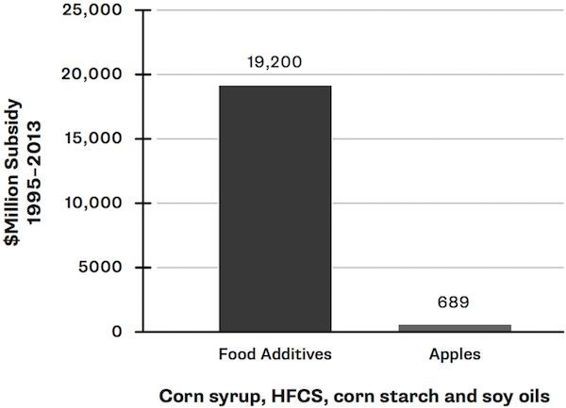

Unprocessed carbohydrates, on the other hand, receive virtually no financial aid. While mass production of corn and wheat receives generous support, the same cannot be said for cabbage, broccoli, apples, strawberries, spinach, lettuce and blueberries. Figure 12.38 compares the subsidy received for apples to that received for food additives, which includes corn syrup, high-fructose corn syrup, corn starch and soy oils. Food additives receive almost thirty times more in subsidies. Saddest of all, apples receive the most, not the least, federal aid of all the fruits and vegetables. All others receive negligible support.

Figure 12.3. Food additives are subsidized far more heavily than whole foods.

The government is subsidizing, with our own tax dollars, the very foods that are making us obese. Obesity is effectively the result of government policy. Federal subsidies encourage the cultivation of large amounts of corn and wheat, which are processed into many foods. These foods, in turn, become far more affordable, which encourages their consumption. Large- scale consumption of highly processed carbohydrates leads to obesity. More tax dollars are then needed to support anti-obesity programs. Even more dollars are needed for medical treatment of obesity-related problems.

Was this a giant conspiracy to keep us sick? Doubtful. The large subsidies were simply the result of programs to make food affordable, which began in earnest in the 1970s. Back then, the major health concern was not obesity, but the “epidemic” of heart disease that was believed to be the result of excess dietary fat. The base of the Food Pyramid, the foods to be eaten by each of us every day, was bread, pasta, potatoes and rice. Naturally, money flowed into subsidies for those foods, the production of which was encouraged by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Refined grains and corn products soon became affordable by all. Obesity followed like the grim reaper.

It is noteworthy that, in the 1920s, sugar was relatively expensive. A 1930 study9 showed that type 2 diabetes was far more common among the wealthier northern states compared to the poorer southern states. As sugar became extremely cheap, however, this relationship inverted. Now, poverty is associated with type 2 diabetes, rather than the other way around.

EVIDENCE FROM THE PIMA PEOPLE

THE PIMA INDIANS of the American southwest have the highest rates of diabetes and obesity in North America. An estimated 50 percent of Pima adults are obese, and of those, 95 percent have diabetes.10 High levels of obesity are once again seen alongside grinding poverty. What happened?

The traditional Pima diet relied on agriculture, hunting and fishing. All reports from the 1800s suggest that the Pima were “sprightly” and in good