CHAPTER VI

THOSE DARK-EYED SEÑORITAS!

I

It was evening when the train brought Eustace and myself into Mazatlán. Since the fortnightly steamer was scheduled to sail for the south at eight o’clock, we leaped into a cab, and ordered the cochero to drive like fury.

He whipped up his slumbering nags, and we rattled toward the wharf, through conventional narrow streets lined with the traditional fortress-like houses of Latin America. But—although it may have been the effect of the tropical climate—it seemed that each balcony or window was occupied by a señorita infinitely more attractive than any that had occupied the same sort of balcony or window in the same sort of dwellings in any of the previous cities.

“Whoa!” called Eustace. “In the interests of journalism, let’s have a longer look at this town!”

But before the interests of journalism were fully satisfied, the steamer whistled from the harbor, and our cochero whipped up his horses again. On we rattled until we came to the plaza. It was an unusually attractive plaza. There were royal poincianas, tinkling fountains, and—

“Whoa!” called Eustace. “In the int—”

The plaza also appeared to be inhabited by what evidently was the most abundant product of Mazatlán. But the steamer whistled again, and the whip crackled, and we careened wildly around sharp corners to the harbor. It was a delightful harbor. A semi-circle of driveway bordered it—a driveway lined with graceful cocoa-palms that whispered softly in the gentle breeze. A newly risen moon peeped through their fronds, and sparkled along the wide expanse of sea, tipping each wave with a streak of silver as the swells rolled in from the Pacific to shatter themselves in gleaming spray against the rocks before us. From the thatched cottages of the fisher-folk across the bay there drifted to us the tinkle of a guitar. And from the city behind us sounded the chimes of a cathedral clock. It was striking eight—the hour our steamer was to sail.

“Hurrah!” we shouted. “We’ve missed it!”

II

We had just acquired the mental attitude requisite to appreciation of Mexico—a state of unworried and unhurried tranquillity such as enables the Mexican himself to sit all day on a plaza bench, enjoying the balmy southern breezes, smoking innumerable cigarettes, discussing nothing in particular, watching the other idlers, and admiring the beauties—both animate and inanimate—of the whole pleasant scene.

Mazatlán had been designed for people with such a mental attitude. The climate was balmy. The whole city was quaintly Mexican. There was not a tourist sight in town. There was, in short, nothing to do except to sit in the plaza—such a plaza as might be found in any other Mexican city, a little square park with a music kiosk in the center, surrounded by palms and ferns and shaded walks, and with an aged white cathedral for its background. Sitting there, one saw the entire population pass in review, for as elsewhere in Mexico, the plaza was at once a club, a meeting place, a music-hall, a playground, and even a marriage market.

III

On my first morning, fortunately a Sunday morning, while I still retained a slight vestige of Anglo-Saxon energy, I was there at daybreak, determined to observe minutely what transpired.

At 6.30, the only other occupants of the benches were several ragged beggars.

At 7.00, the Mazatlán Street Cleaning Department, both members barefoot, appeared upon the scene, dragging a long hose, whereupon the beggars cautiously adjourned to the steps of the municipal building.

At 7.29, the first bootblack stopped to point accusingly at my shoes. No sooner had he polished them than a dozen other bootblacks stopped to point at them, evidently presuming that shoe-polish acted like alcohol, and that I would now suffer from an insatiable craving for more.

At 7.30, I discovered that wiggling a finger—the Latin-American gesture for “No!”—required less energy than shaking the head.

At 7.47, the first excitement! A policeman’s whistle screamed an alarm! The policeman was chasing a small and very ragged urchin diagonally across the park. The urchin appeared to be gaining, but just as they reached the corner, out popped another policeman, also tooting his whistle, and both pursued the youth up the north side of the square, until joined by a third officer, similarly shrilling the alarm. They disappeared around the cathedral, and the plaza idlers settled back into their seats. Popular sentiment seemed to be with the urchin.

At 7.48, a party of dogs invaded the plaza fountain to enjoy a bath.

At 7.49, a party of peons drove the dogs out of the fountain to enjoy a drink.

At 7.50, the ragged urchin reappeared, having doubled around the cathedral. There were now six cops in pursuit, still tooting their whistles. Pursued and pursuers ran diagonally back across the plaza. At the southeast corner, a seventh policeman dived out from behind a rubbish can, and effected the capture. All marched away with a dignity that emphasized the majesty of the law. The plaza idlers settled back again. No one inquired the wherefore of the chase. All seemed sufficiently pleased that there had been such diversion.

At 8.00, the cathedral bells rang, not solemnly as though in invitation to mass, but rapidly and aggressively, commanding attendance.

At 8.01, two middle-aged male peons entered the church. They wore their shirts outside the pants, in Indian fashion, and were unconcernedly holding hands, like a pair of children.

At 8.35, more excitement! Policemen’s whistles were tooting again. This time a pig had invaded the plaza. Evidently pigs were not allowed there except when muzzled and on leash. Six policemen, assisted by a full corps of bootblacks, chased the snorting little porker around palm trees and through the flower beds.

At 8.37, the policemen formed an escort, and marched away again, still with dignity and majesty, escorting the latest captive to the police barracks.

At 9.00, the cathedral bell resumed its unhallowed racket.

At 9.08, Carmen Rosa María de la Concepción Purísima Rodríguez, who lived upstairs opposite the plaza, commenced her piano lesson, playing those rippling little Spanish melodies, with occasional pauses while she searched for the bass note.

At 9.09, I decided to stroll to the other side of the park.

At 9.10, I found Eustace sitting on a bench with a distinguished-looking middle-aged American who, I hoped, would gratify my ideas of romance by proving an absconded bank cashier. But he was introduced as a mining man by the name of Werner. He was eating oranges and tossing the peels into the shrubbery, meanwhile bowing to the celebrities who passed. “Here comes General Cómo-se-Llama, the worst cut-throat in Mexico. Hello, General, muy buenas días, how are you?”

At 9.11, a second general passed, in a uniform which he had designed himself—sky blue cap, bright red coat, and green trousers, all embellished with gold braid. He was five feet high, and four feet wide. “They use him for dress parade,” said Werner.

At 9.12, a third general passed, marching through the street, followed by eight soldiers.

At 9.49, the first pretty señoritas, on their way to mass with a forbidding-looking mother, stopped to rest on the bench opposite. The girls wore the latest Parisian modes, but mother still clung to the old-fashioned rebozo, or shawl. Each wore a little black lace mantilla pinned to the hair. One girl noted that we were looking at her, and her eyes twinkled appreciatively. She whispered to the other girl, and both smiled.

At 9.51, after an accusing glance from mother, we decided to stroll around the plaza. “They’ll consider it an insult,” said Werner. “They expect you to stay here and talk together about how lovely they are, just loud enough for them to hear it.”

At 10.26, the musicians gathered for their Sunday morning concert. Having tuned up, they continued to blow and toot, indulging the Mexicans’ love of noise. Half of them were unshod; all were brown; none looked like accomplished artists. I dreaded the racket they’d make when all tooted at once.

At 10.30, they played the most beautiful band music I had ever heard.

At 10.52, society emerged from the cathedral. Barefoot peons withdrew from the plaza to make room for the aristocrats.

At 11.00, the beggars became active. The blind men closed their eyes, and the cripples started to flop. They wriggled from bench to bench; they suffered themselves to be led by little children; they crawled in snake-like twists and propelled themselves in frog-like jumps; they hobbled upon crutches; they stumped upon legless knees; they turned over on their backs and squirmed upside down. At each bench, they would whine in plaintive voice, “A little penny, for the sake of God, señores!” The Mexicans liked this. They regarded beggars as an institution that enabled them to gratify personal vanity by giving alms. It did not cost much. And they regarded curse or blessing with superstitious respect. So the procession hopped and flopped and squirmed and for-god-saked unmolested all around the park.

At 11.10, the Promenade was in full swing. The elders kept a watchful eye on their daughters from the benches. The youths draped themselves gracefully on their canes along the outer walk. The girls, in merry groups of twos and threes and fours, arm in arm, swung past on exhibition—dainty little creatures, fairly radiating sweetness and modesty, yet keenly aware of the masculine admiration they aroused, quick to notice if a youth’s gaze lingered, ready to exchange opinions in whispered conference, ready even to respond with a brief flash of eyes, supremely self-assured, yet never bold. From childhood they had paraded this plaza, accustoming themselves to the sensation of being on exhibition. They liked to be looked at. It brought a flush to their cheeks, and a luster to their dark eyes. This was their only opportunity, in an existence of semi-seclusion, to see and to be seen. There were stolid-looking maids in the procession, carrying babies all done up in silks and laces. There were little girls of ten and twelve, already practicing coquetry. And there were innumerable maidens of fifteen and twenty, suitable for marriage, and watching the circle of young men for an indication that to-day’s parade had awakened the divine fire.

At 11.20, the first youth fell. He detached himself from the onlookers and—accompanied by a companion who carefully showed his neutrality by a super-nonchalance of manner—followed one of the damsels around and around the square, affecting a melting expression of countenance, and beseeching her with melancholy eyes for a backward glance. The girl’s companions nudged her and giggled; the girl herself pretended to be unaware that she was followed; but the flush heightened in her cheeks, and her eyes sparkled.

At 11.59, the families reassembled, and moved homeward, each a parade by itself. The enamored youth gazed in the proper affectation of despair after his departing maiden, and gave an imitation of a candle that has been extinguished.

At 12.00, Werner announced that the bench-slats had stamped him with an accordion-pleated design, and left us.

At 12.01, two surviving señoritas—the two of the 9.49 episode—stopped at our bench, and seated themselves coyly at the far end.

At 12.02, a boy sold us three bags of peanuts for a nickel.

At 12.04, not knowing what to do with the third bag of peanuts, I offered it to the señoritas, and was rewarded with a “Gracias” which could not have been sweeter had the offering been a five-pound upholstered box of the most expensive chocolates.

At 12.05, the observations inscribed in my now-faded notebook during those first vestiges of Anglo-Saxon energy, appear for some reason to have ceased.

IV

As I recall that first conversation with Herminia and Lolita, it ran somewhat as follows:

Were we from the United States? Ay, what a wonderful country must be the United States! How they would love to go to a land where women enjoyed such freedom! And American men respected women more than did the Mexicans. But how long were we remaining in Mazatlán? So short a time! Why did we not stay longer? Did we not think Mexican girls as attractive as American girls? Ay, but we were very polite to say such nice things! Still, did we not have wives at home? Not even sweethearts? No? Then why should one be in such haste to leave Mazatlán? Ay, Dios! The cathedral clock was striking twelve and a half, and their family would scold them for lingering so long! But they came to the plaza every evening at eight. Yes, always at eight. Adios! And again muchas gracias for the peanuts!

V

The plaza became a very definite habit to Eustace and myself. At home, we could never have loitered day after day in a park, doing nothing, but in Mexico one could. The other idlers were always interesting. Some amusing little incident was always happening. Yet nothing ever seemed to disturb the prevailing restful calm.

Herminia and Lolita were always there at eight.

They were slender little girls, with the delicately molded features and the immense dark eyes characteristic of their race. They were adept, too, in the use of those eyes—as all Spanish girls are adept—yet if, to a casual observer they appeared flirtatious, they proved upon further acquaintance—as all Spanish girls prove—to be quite the most shy, and modest, and altogether circumspect little misses to be found anywhere in the world.

For some inexplicable reason, the Spanish señorita has been most inaccurately portrayed in our fiction and drama as a wild vampire, modeled after the operatic Carmen, until the average American pictures her as a fiery adventuress who lifts one shoulder higher than the other and curls her sensuous lips into a sinister smile destined to wreck the life of every passing bullfighter.

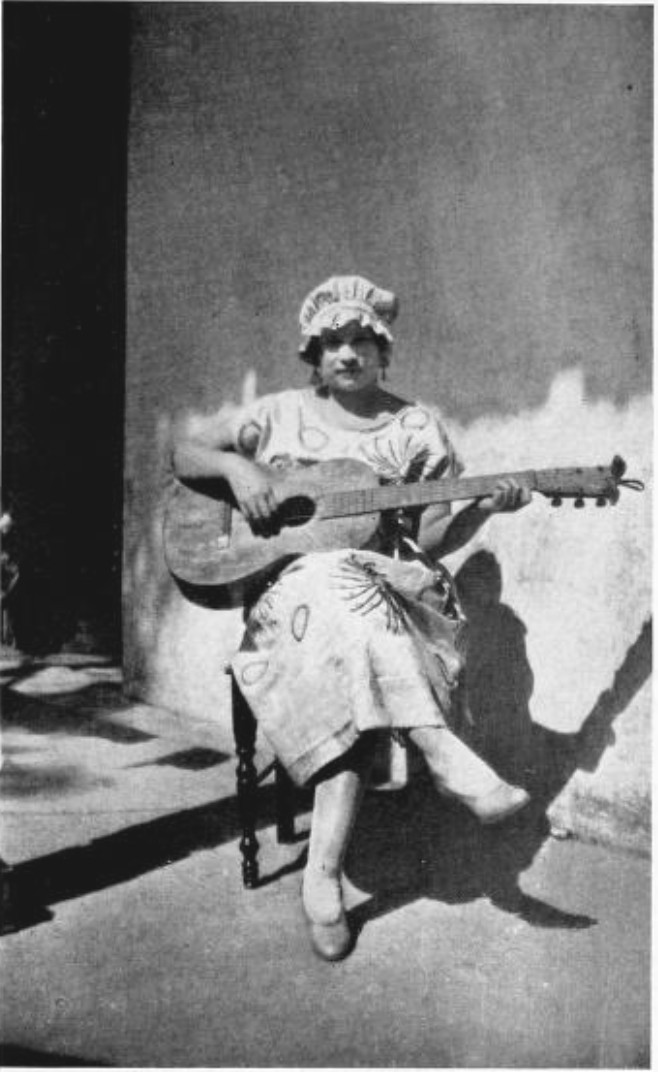

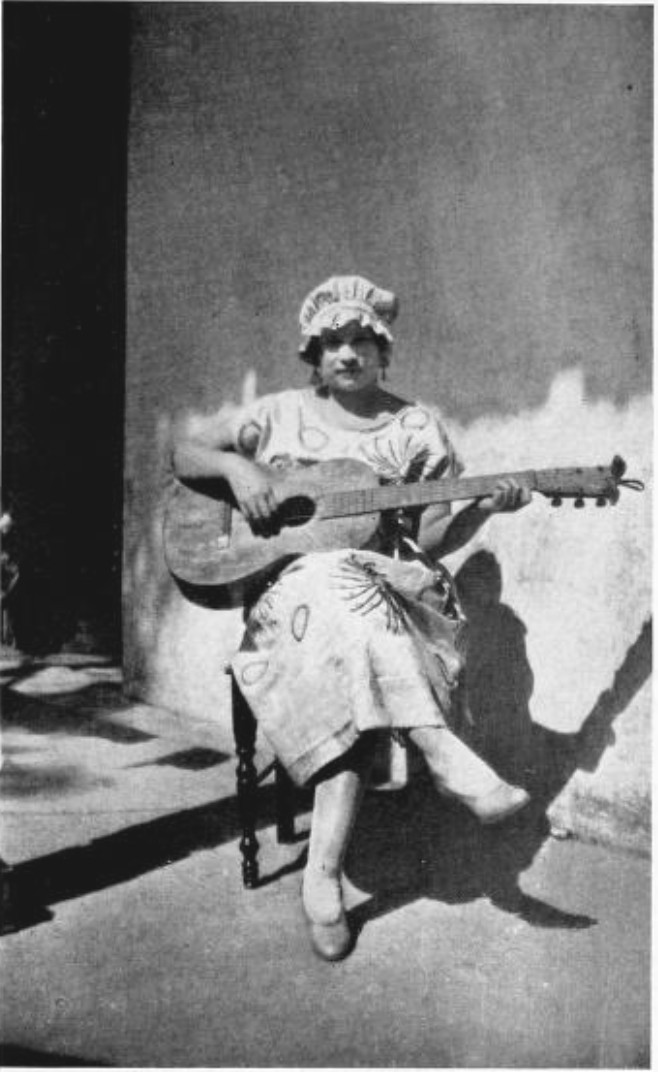

THE MEXICAN SEÑORITA HAS ALWAYS BEEN PORTRAYED IN OUR FICTION AS A WILD VAMPIRE

In real life, the Mexican maiden—and one might include her sisters of Spanish ancestry—is, with all her mischievous smiling—the most timid, sedate and well-behaved little miss that can be found anywhere. She lives at home in semi-seclusion. She never appears in public without a chaperon, except possibly to stroll with another maiden to the shops or the plaza. She is at all times guarded against the machinations of wicked males—who are always assumed to be predatory animals until they indicate very definitely that they intend marriage, and who are by no means to be trusted even then—and she never meets a man except where others are present or when the window-bars afford insulation for her virtue.

In the more cosmopolitan centers, where the daughters of the wealthier families have been educated abroad, and where parents have adopted a foreign viewpoint, this close guardianship is often relaxed. But in the smaller city, like Mazatlán, the señorita is still the victim of a social system carefully designed to protect her against a race of men whose mind dwells almost exclusively on sex.

The Mexican—even more than most of his brothers of Spanish ancestry—while he publicly extols women as the most exquisite handiwork of God, privately regards them as instruments exclusively for the gratification of natural instincts. Although he may talk eloquently of love, he is incapable of any infatuation which is not based primarily upon sex appeal. But, since he is a jealous creature, and since he knows that his brothers, like himself, would take advantage of any opportunity for seduction, he demands that his wife be a model of unquestionable propriety.

And the Mexican maiden, brought up to believe that her only aim in life is to attract a husband, smiles quite alluringly, and leads conversation to sentimental themes, yet remains most circumspect. In her smile there is a promise, but her family will see that the promise is not fulfilled until marriage.

Even in love there is nothing genuinely impulsive about the Latin of either sex. He, originally, is motivated by the desire to possess something more attractive and exclusive than the females which can easily be found in Latin America, either in officially segregated districts or among the servant classes. She, originally, is motivated by a desire for home and children—a desire not unknown among the women of other countries, but far keener in lands where, despite the inroads of foreign custom, there is still but little amusement for women except the care of babies.

Romance, in the beginning, is as carefully studied by the Latin as is his politeness and his every other quality. Once begun, since he is an adept at self-hypnotism, it may become a thing of tremendous emotion. Yet the courtship at all times follows an extremely formal course. The youth, charmed by a maiden’s smile (and having made inquiries about her family), follows her home from the plaza night after night, and leans against the opposite wall to stare at her window until she, finally captivated by his persistence (and having made inquiries about his family), allows him to coo at her through the bars. At length he makes a formal call, announces his intentions, and is duly accepted by her parents, who thereafter welcome him to the parlor, but seldom allow him alone with the daughter.

It is the ideal system for these people. It may seem absurd to a Gringo, yet it is quite satisfactory to the Spanish-American. The barriers that surround the girl prove to him that others have not been able to reach her. If they prevent him from learning her disposition, it does not particularly matter. He knows that she has been brought up with the idea of becoming an obedient wife. He does not expect intellectual stimulation from her companionship. He can see that she is beautiful and desirable. And if there has been an element of premeditation in the beginning of his courtship, his mental habit of dwelling almost exclusively upon sex will soon arouse a keen desire which the tantalizing window-bars merely aggravate.

Yet after marriage, children usually bring something akin to a higher love. The man may not remain faithful, but he will provide for his wife, and honor her, and accord her every respect. She, having accomplished her chief aim in life, will forget herself in her devotion to husband and offspring. She will grow fat and sloppy, and spend most of her time preparing daughters for their chief aim. But at all times, unlike the Carmen of fiction, she will be modest and reserved, and faithful to a degree seldom found elsewhere in the world.

If Herminia and Lolita gave us a longer flash of eyes than was customary, at eight o’clock in the plaza, they were not adopting Carmen’s tactics. They were merely two of many girls in a small city which, like most small cities, was equipped with comparatively few men to smile at.

VI

At that time, Eustace and I knew very little about Spanish custom.

We looked upon our mild flirtation as a pleasant and instructive way of spending the evening while waiting for another boat.

Herminia and Lolita would pass us two or three times, always with that promising flash of eyes, and a murmured “Adios.” Presently they would stop at a bench beyond, and glance back. Thereupon we would rise, stroll around the park as we had seen Mexican youths do, and stop casually, as though by accident, at the girls’ bench.

And conversation, as I recall it, invariably ran somewhat as follows:

Ay, but one was surprised that to-night we came to their bench! After the way we had stared at Carmen Rosa María de la Concepción Purísima Rodríguez, one expected that we might have gone to her bench. Ay, but both of them had seen! And Carmen Rosa María was the most beautiful girl in Mazatlán, no? No? Then who was? Ay, gracias, gracias, señores! So nice it was that we should say so! Did we really think so? Ay, but we were simpatico—muy simpatico—to say it!

Then commenced the Spanish lesson. It seemed, at times, a trifle impractical, for it was usually limited to phrases conveying admiration of feminine charm. If the male Latin-American revels in flattery, the female lives upon it, and these two señoritas were merely typical of most of their sisters in Mexico. A young man in their country was expected to spend the entire evening raving about their beauty. It mattered not how elaborate were his phraseology; he could expand his theme to a degree which would have brought any American flapper to her feet with the disgusted exclamation of, “How do you get that way? Do you think I’m a dumb-bell?”, yet here it was not only accepted, but demanded. This, as any traveling Gringo soon discovers in Mexico, was the theme most interesting to a señorita.

I suspected, at times, that I lacked the true grace of the Spanish cavalier. Since my command of the language was still somewhat limited, it was necessary to repeat the same phrases with tiresome regularity. I became aware of a foreboding, as we sat there beneath the coco-palms, that if I recited those phrases once more, all the cocoanuts would drop on me.

But when I suggested, as a change of entertainment, that we stroll over to a little café on the harbor-front for ice cream, the señoritas were quite shocked.

Ay, but one was now in Mexico! It was not custom! People would talk! And was it true that in the United States the girls—nice girls—could do such things? One had heard so, but it sounded incredible. One had even heard that young people went away, without chaperones, to theaters or dances. And was this true? One had actually heard that there were petting parties. How delightfully wicked! Ay, what a wonderful place must be the United States!

There was a pleasing simplicity about these little convent-sheltered maidens. If they craved flattery until it seemed a bit monotonous, one could at least pay it with veracity. And the plaza, although it was overpopulated with observers, was always pleasant. One had the illusion, particularly in the evening, that it was a theater where one collaborated with the rest of the populace in enacting a polite comedy-drama. The palms and ferns hung lifeless in the tropic calm, and the red hibiscus resembled paper flowers. The old cathedral transformed itself into a backdrop. The strains of the band came to one as from an orchestra hidden off-stage. There was something unreal about the soft whispers and the rippling laughter of the other youths and maidens. And when, as the chimes announced the hour of ten, the señoritas betook themselves homeward with cheerful little calls of “Adios until to-morrow!”, I waited expectantly for a curtain to descend.

One evening, after the girls had departed, Werner stopped at our bench.

“Just thought I’d warn you,” he said. “I know you don’t mean any harm. There’s something about this place that makes one lonesome for feminine company. But down here, unless you show very definitely that you intend marriage, they take it for granted you’re up to monkey business. So just go easy, or you’ll have their family jumping on your necks.”

We thanked him. It was timely advice. And when, on the following evening, the girls suggested that we meet the family, we agreed. It seemed advisable as an indication of the highly sanitary state of our consciences.

Theirs was the usual one-story dwelling of solid masonry characteristic of the country. A faded and crumbling plaster front concealed a pleasing, albeit conventional interior. The living room was floored with cool tiling. The furnishings—except for a piano with yellowed keys, and a marble-topped table littered with forbidding pictures of stout female ancestors—consisted mainly of stiff-backed chairs formally arranged in a row along each wall; yet the conventional effect was relieved somewhat by numerous white lace doilies on the seats, or by potted palms which gave the room the semblance of a garden.

The family proved gracious, but not entertaining. Papa and mama assured us that the house was ours—as is customary when a stranger enters the Latin-American home. Then, one by one, they brought forward their relatives and presented them—a daughter or two, several sons, a few cousins, nephews or nieces, a flock of aunts, some assorted uncles or brothers-in-law with their respective families, and finally grandma. Having informed us in turn that they were our servants, they took seats until the walls were lined with them, and silence fell upon the gathering.

Papa opened the conversation with a pleasant inquiry regarding the object of our visit to Mazatlán. Ah, we were writers! An admiring nod ran around the circle, finally reaching grandma, where it stopped momentarily until Uncle Somebody transmitted our answer through an ear trumpet. Grandma seemed a trifle perplexed, as though she did not know just what writers might be, but she nodded politely. Thus the conversation proceeded, papa acting as spokesman for the entire party, until—after the ordeal had continued for an hour or more—a servant entered with glasses of vermouth, and our reception closed in a toast proposed by papa to the “very distinguished guests, who have honored our humble household to-night.”

Our necks seemed to be free from the likelihood of assault, for upon the following evening the girls announced that they had permission to stroll beyond the plaza, as far as the driveway that bordered the harbor.

“Never have our parents permitted it with our own countrymen,” they added. “Our people trust Americans more than themselves.”

To show our appreciation, we took the girls home each night, even though it involved another session at which the family lined up around the wall to nod while papa conducted another tedious conversation. Yet, if we were occasionally bored, our two weeks passed rapidly.

VII

Our steamer finally whistled from the harbor. We had already purchased our tickets, and were on our way to bid the señoritas farewell, when Werner intercepted us, waving a newspaper.

“Congratulations, boys! You’ve picked out mighty nice girls!”

Papa, it seems, had announced our engagement without consulting us. It was in the daily journal of Mazatlán!

“Why, good Heavens! Look here, Werner, we haven’t said a word to them! We called at the house every night, and we walked along the Olas Altas, with the permission of the family, but—”

“Oh, you called at the house every night! That’s the worst thing you could have done, my boys! That’s considered an avowal down here—especially since the town’s full of marriageable daughters with scarcely any men in sight! And it’s taken for granted, of course, that all Americans are millionaires. So you’re engaged all right. Now, what are you going to do about it?”

“I can’t think of any suggestion,” said Eustace, “except that we run like the devil for that boat.”

Werner shook his head.

“That means the girls are ruined for life. When a man breaks the engagement, it’s assumed that he’s learned the girl wasn’t chaste, or that he’s succeeded himself and doesn’t want her any more. No one else would marry them after that. And it’s hell to be an old maid in Mexico.”

We were somewhat appalled. They were really very lovely little girls. But a Gringo couldn’t pay compliments night after night for the next fifty years. And one thought, too, of grandma and her ear trumpet, and a solemn circle of relatives, and a table littered with pictures of forbidding-visaged female ancestors.

“There’s one way out,” said Werner. “Say good-by to them as though you were going on a short business trip. From Manzanillo wire me that you were shot by bandits. That’ll clear the girls. Hurry now, or you’ll miss another boat. And by the way, when you wire me that you’re dead, don’t sign your own names.”

VIII

At 7.49 p.m., having recovered the last vestiges of my Anglo-Saxon energy, I drove with Eustace to the house, and bade the family farewell. The girls appeared a trifle distressed, but not so much as we felt they ought to be. The family knew intuitively that we were fleeing, but with true Mexican politeness they accepted our explanations as though they believed.

At 7.52, we leaped back into the cab and ordered the cochero to drive like fury.

At 7.56, we passed the plaza, but paused not in the interests of journalism.

At 8.00, we sailed out of Mazatlán’s attractive harbor, where the moonlight sparkled along the wide expanse of sea, and the tinkle of a guitar came to us from the thatched cottages of the fisher-folk, as though it were an accompaniment to the chimes of the old cathedral clock that we knew so well. Eight o’clock! Herminia and Lolita would be strolling in the plaza, where the strains of the band, as though from an orchestra off-stage, blended with the r