CHAPTER VII

IN THE DAYS OF CARRANZA

I

The steamer plowed southward through a dazzling blue sea to Manzanillo, the port of disembarkation for Mexico City.

Despite its commercial importance, this is one of the several places on the Pacific Coast where a traveler, upon leaving his ship, takes one hasty glance at the dirty black beach and the cluster of driftwood shacks, grasps his nose firmly between thumb and forefinger, and makes a dash for the daily train that will carry him somewhere else.

As soon as a boatman had rowed us ashore, Eustace and I hastened to the telegraph office, and dispatched our message to Werner: “Foster and Eustace slain by bandits.” Then we ran for the train. But, although an excited crowd surrounded the station, there was no train in sight.

“There will be none to-day,” explained the agent. “Zamorra stopped it just outside of town, wrecked it, and shot most of the passengers.”

II

By sheer coincidence, our message to Werner had been seemingly confirmed. Following the news dispatch of this hold-up, which undoubtedly would reach Mazatlán, the notice of our murder would carry conviction. For the moment, we were delighted. Then the agent added:

“There may be no train for several weeks.”

And we found ourselves stranded in the filthiest hole in Mexico. Manzanillo’s streets were of thick sand, inadequately paved in spots with refuse or garbage, over which hovered millions of flies, and about which a host of black buzzards were picking and quarreling. The whole town was perched upon a narrow landspit between the murky bay and a still murkier lagoon, and backed by low hills whose scraggly jungle-growth the tropic sun had burned to a crisp. A few buildings of wood or plaster rose to the majesty of a second story; the others were low and of ramshackle structure, their driftwood composition varied occasionally by patches of flattened tin that had once done service as Standard Oil cans. The roofs were mainly of thatch. Interior decoration, as glimpsed through doorless doorways, was limited to pages from the local equivalents of the Police Gazette. Over the whole unsightly place there hung an odor of rotted fish, emanating from neighboring lagoons which had evaporated throughout the long dry season to nothing more than a crust of reddish scum.

The principal virtue of the leading hotel—a wobbly two-story edifice operated by a Chinaman—was that it possessed enough odors of its own to neutralize the fishy breezes from the lagoon. The food was nauseous and the water poisonous. The natives of the town quenched their thirst at the stagnant jungle pools by rolling up a leaf into the semblance of a funnel, poking it through the inch of scum that covered the water, and drinking the fluid beneath with ecstatic sucks. Cautious foreigners were forced to patronize the hotel bar, where the beer ascended in temperature from lukewarm in the morning to some degree near boiling point in mid-afternoon.

Determined to make the best of our indefinite residence, we looked about for amusement.

There was always the beach. Its sand was black, and the rollers assumed the shade of molasses. The women of the town, since Mexican women are too modest to wear short-skirted bathing suits, always took their bath in a clumsy white linen gown which reached to the ankles, but which, as soon as it was wet, became completely diaphanous. They were as dark, usually, as the beach, and the silhouette effect was highly educational.

When the sights of the waterfront had received due attention, we retired to the lagoons to hunt alligators. In the larger pools, which had not completely evaporated, we could see the corrugated tails of the big caymans tracing a leisurely path across the surface, and occasionally by making our way silently along the brush-grown shore, we could surprise a greenish-gray monster asleep on the mud-flats. Our diminutive pistols seemed to have little effect on their tough hide; our shots brought only a splash as the quarry plunged into the lagoon; a few bubbles would rise, and a muddy discoloration of the water would indicate that the alligator was safely imbedded in the loamy bottom of the pool. We tried to lasso one of them, with a loop of rope on the end of a pole, but the monster vanished, as usual, carrying with him the stoutest cord to be purchased in Manzanillo.

From alligator-hunting we turned to a study of natural history in general. The town and its environs offered plenty of material. One could scarcely walk the streets without shooing buzzards out of the way. Sooty black in color, with ashen-gray neck curved to suggest hunched shoulders, they hopped about with rocketing step, pouncing with hoggish squeals upon rotted carrion, and squabbling among themselves over its possession. One was tempted always to try the pistols on them, but they were protected by law, for without their services in disposing of the mess which Latin-American servants are accustomed to toss from the kitchen window, cities like Manzanillo would be altogether uninhabitable.

Of insects there was an infinite variety. We did not have to seek them; they sought us. One could not push through the jungle without being bitten by ants on the bushes. In the town itself, half the population seemed to find constant occupation in picking something out of the other half’s hair. The peon women would form a small circle, back to back, and perform this friendly little operation with one-hundred-per cent. efficiency. In the hotel room the scratchy noise of cockroaches scrambling up and down the wall lulled us to sleep each night.

Eustace, not content with this material for study, took up snakes in a serious fashion. He had once earned his way through college by feeding the reptiles in a neighboring zoo, and had formed a strange affection for them. He maintained that they recognized him as a friend and refused to bite. In Manzanillo he discovered a family of young serpents—squirmy green fellows which we could not identify but which the natives regarded as extremely venomous—whereupon he brought a handful of them to our room, and dumped his other possessions out of his suit-case to make a home for them. Later, when I absent-mindedly opened the same suit-case in search of cigars, and fled precipitately, our Chinese proprietor was greatly incensed because for days afterward the snakes would appear at the most unexpected moments in various parts of the establishment, to the terror of servants and guests.

It not only worried his regular boarders, he said, but ruined trade at the bar. After a drink of hot beer, when a patron saw these things writhing across the counter—well, just yesterday the mayor himself had overturned a whole tray of glasses, smashed two chairs in his haste to reach the open air, and had not returned since! And the mayor was one of his best customers!

III

The bandit attack upon the train had occurred so close to the city that the Carranzista garrison threw up temporary barricades on the approaches to town.

Instead of sallying forth to pursue the bandits, however, the soldiers contented themselves with a daily parade across the plaza, led by a wheezy band of four pieces, intended presumably to reassure the civilian population.

The local commandante had suddenly assumed an air of great importance. He was a tall man with broad but extremely thin shoulders, with a wasp-like waist, and with legs that tapered toward the ground until one marveled that he could maintain his equilibrium in a stiff breeze. As though to accentuate the top-heavy effect, he wore the largest-brimmed sombrero in Mexico, a pair of moustachios that curled in several spiral twists, a flowing red necktie, six kilometers of cartridge belt, and a massive old rifle, while he clad his slender ankles in skin-tight Spanish trousers of a type seldom seen to-day except upon the stage.

Seeing him alone, one felt that the rank of general was too little for him. Seeing him with his twenty valiant soldiers, one felt that the grade of corporal was too much.

The first qualification for a federal soldier in Mexico appears to be that he shall not exceed four feet in height. He comes invariably from the very lowest rank of society, which in Mexico is extremely low. He represents the poorest—and frequently the worst—specimen of humanity in the republic. In the days of Carranza he was ununiformed, except in the capital, and usually barefoot. He was generally dirty and unshaven, and his principal occupation seemed to be that of lounging on street-corners, insulting passing servant maids.

No motive of patriotism had prompted his enlistment. In some cases he was a mere boy attracted by the privilege of carrying a rifle. In others, he was a peon drafted against his will. In others, he was some old devil who could earn a living in no other fashion. Having been issued his arms, he became a full-fledged soldier. No one drilled him. He was allowed to wear whatever clothes he already possessed, although a faded pair of overalls was considered especially de rigeur. Sometimes he received a peso a day, sometimes nothing. When I was in Mazatlán, a federal paymaster newly arrived with a satchelful of gold for the local garrison was giving such an elaborate series of booze-parties to his friends, that one wondered how much the troops did receive.

Such discipline as the soldiers possessed was due solely to fear of their particular commander. Under a strong man they made pretty fair soldiers. Under a weak man they were quite apt temporarily to turn bandits themselves. Every train in Mexico in those days was accompanied by a guard of them, but they seldom offered resistance in case of a hold-up.

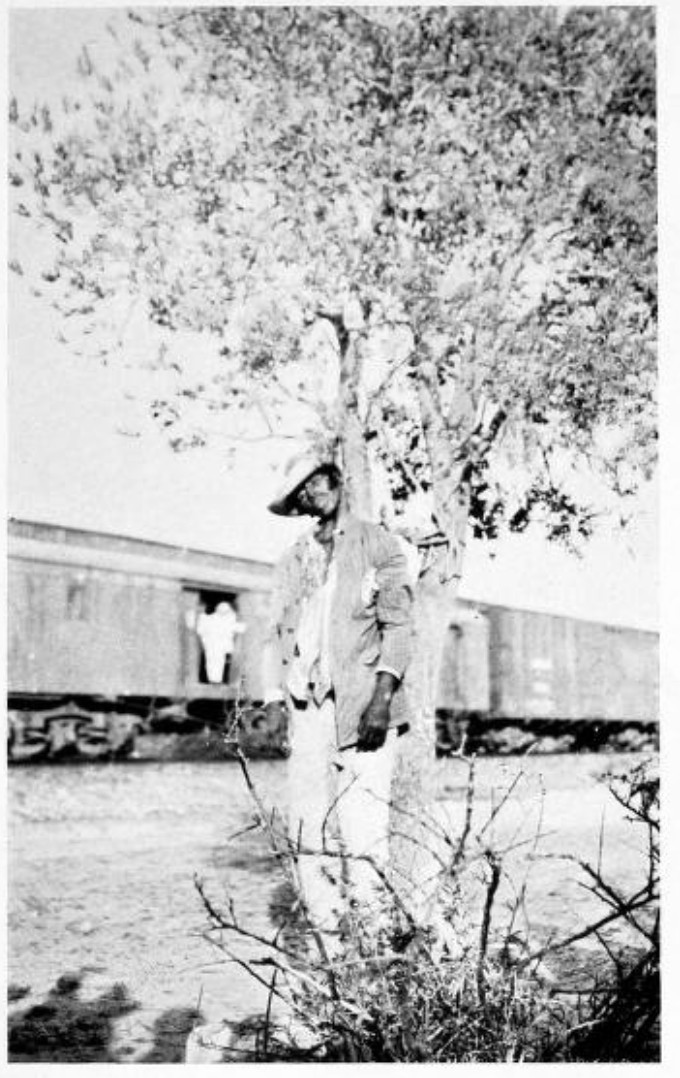

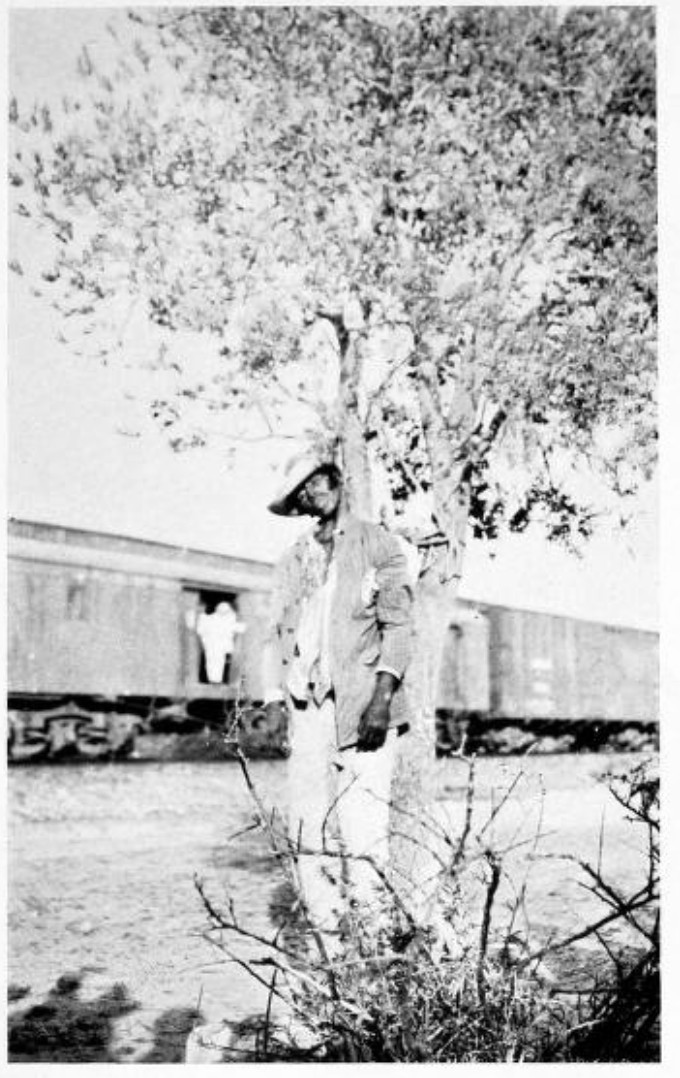

IN THE DAYS OF CARRANZA ONE FREQUENTLY SAW A BANDIT HANGING AROUND THE RAILWAY

“Why should they?” said an Old-Timer in Manzanillo. “The bandits don’t attack unless they outnumber the guard. The soldiers haven’t much chance. If the bandits win, they make a lot of money. If the soldiers win, they get nothing. So they usually cut and run.”

“I suppose that’s what they did when Zamorra held up this train?”

“No. According to reports, they pitched in and helped Zamorra rob the passengers.”

Even though our Commandante marched across the plaza each day behind his wheezy band, Manzanillo was expecting an attack, and there was considerable speculation as to what part the garrison would play. But the gunboat Guererro—one half of the Mexican navy—finally came down the coast from Guaymas, and landed a force of sailors. Under their escort a party of workmen marched out to the scene of the disaster, and we followed them.

It was a jolly little picture. Pedro Zamorra, the local bandido, had twisted the rails and removed a few ties at a point where the train came around a bend. All that remained of the cars was a mess of twisted iron and a pile of splintered boards. A thousand ashen-gray buzzards were picking and quarreling about the wreckage. A thousand more, sleek and content, roosted upon the surrounding hillsides. From the tangled débris the workmen extracted the few remaining bodies of the passengers—very nonchalantly and unconcernedly, as though this were an accustomed task—and heaped them into a gruesome pyramid. A few cans of oil—a match—a bonfire. The buzzards glared in silent indignation at this interruption of their holiday. And the workmen commenced the labor of reconstruction.

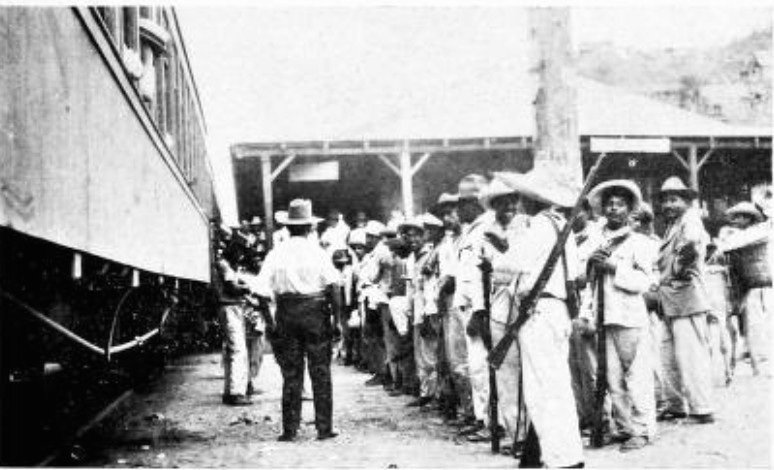

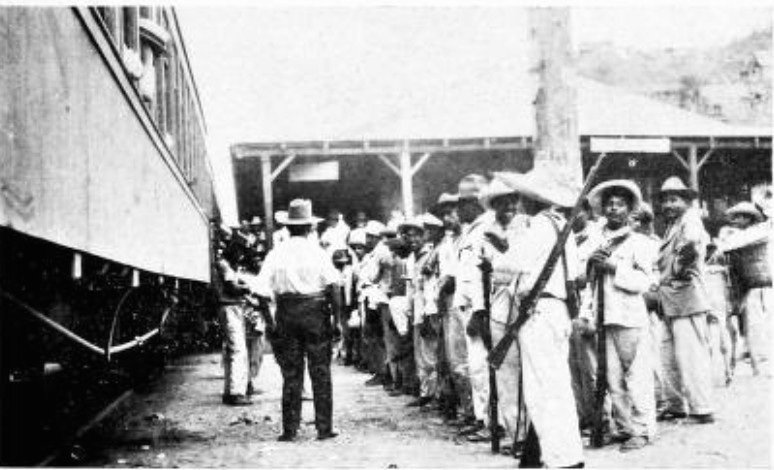

PEDRO ZAMORRA HAD REMOVED A FEW TIES WHERE THE TRAIN CAME AROUND A BEND

IV

This was a common enough spectacle in those days to the residents of Mexico.

For years the republic had been in the throes of civil war—ever since the downfall of the great Dictator, Porfirio Diaz.

Diaz had built up his country by encouraging the foreign capitalist and the foreign promoter. It had become one of the leading nations of the world. But Mexican pride had been wounded at the admission that foreigners were essential to Mexico’s development and prosperity. Mexican jealousy had resented the fortunes which the foreigners were reaping. Mexico had risen to cast out Diaz, and no other man had proved capable of filling his place. Conditions had grown steadily worse, until a dozen revolutionary leaders were squabbling for the presidency, each of them ruling a portion of the republic and claiming to rule the whole.

In an effort to bring order out of chaos the American government—under Wilson and Bryan—had recognized Venustiano Carranza as “First Chief.” With American arms and ammunition, which proved even more useful than the American moral support, Carranza took Mexico City and elected himself president. In the estimation of most Old-Timers in the country, the American government might much better have recognized Pancho Villa or any other bandit. For Carranza, of all the contenders for power, was the leading exponent of the doctrine, “Mexico for the Mexicans!” His first move was to promulgate a new constitution, in many ways a splendid document, but one that gave every right to the workman and none to the capitalist. The foreigner promptly withdrew. And Mexico, in the hands of the Mexicans, enjoyed a complete economic collapse.

Without employment, the peon everywhere turned to banditry as the only profitable occupation. Rebel leaders continued to dominate many sections of the republic—Villa in Chihuahua, Pelaez in the Oil Fields, Felix Diaz in Vera Cruz, Meixuerio in Oaxaca, and others elsewhere. And even in the territory nominally under Carranza control, gentlemen like Pedro Zamorra were popping up from time to time to spread a few rails, remove a few ties, pitch a railway train over a cliff, and provide another holiday for the buzzards.

V

Each evening in Manzanillo, when the beer had lost its mid-day warmth, two or three Old-Timers, stranded like ourselves, would gather at the bar to discuss conditions.

The Old-Timer in Mexico is very much of a type.

He is usually a quiet, unassuming man, with grizzly gray hair, and friendly blue eyes. He came from somewhere in the West or Middle West, so long ago that he has forgotten just when. He owns a mine that has ceased operation pending the arrival of better times. He is easy-going and fatalistic, a trifle careless about dress, blunt in manner yet with a natural kindliness, slow of movement from long residence in the tropics, and very fond of talking about “these people,” by which he means the Mexicans. During the last revolution they took all his money away from him, and smashed up his mine, but he still cherishes an affection for them. He is waiting hopefully for another Diaz to bring prosperity back to Mexico.

He is a trifle reticent at first about talking. He is surprised that the itinerant writer regards him as an interesting character. But he is secretly very much pleased. Gradually he commences a yarn. It suggests another, and that one suggests another, until they follow in rapid succession.

Quoth one:

“I always used to carry a gun. Nowadays I’m afraid to. It’s getting too dangerous. You can’t tell who’s a bandit. Some one comes riding up to you, looking like any other peon, and just as he reaches you, his blanket slides off his shoulder and you’re looking into the muzzle of a six-shooter. Like as not, too, he’s got some pal covering you from the brush. If you’re armed, they’re likely to make it a sure thing by shooting you first and robbing you afterward. So, when I hit the interior nowadays, I just take a bottle of tequila. When I meet a bandit, I show him I haven’t anything worth taking, and offer him a drink, and that ends it.”

Quoth another, a mining man from Durango:

“You see, there’s good bandits and bad bandits. Lots of ’em are chaps as can’t make a living no other way. And some’s just kids that think it’s smart, and do it because it’s so easy. Take Trinidad, down below Rosario. Just a youngster, but he’s got the police buffaloed. Rides into town in broad daylight and covers the barber with a Colt while he gets shaved. Shoots up a dance-hall now and then, but don’t do much real harm.

“Only trouble with Trini is that he likes women. He come down from the hills one day with five of his gang, going to Rosario for something or other, and on the way he seen a fifteen-year-old girl—daughter of some rancher. Says he to the father, ‘I’ll stop to-morrow and take her along home with me.’ Well, the father wasn’t thrilled at having Trini for a son-in-law, especially so informal-like, so he sent to town for protection, and got a couple of dozen soldiers. They was all asleep in the shade next afternoon, when Trini gallops up, swings the girl on his saddle—most of these country kids think it’s kind of romantic to be taken away like that—and off he goes with her. The soldiers chased him, of course, but he held them off in a mountain pass ’til dark, and got away with her.

“That’s the way things are these days. I’m still trying to run my mine up in Durango, and I’m paying taxes to Carranza for protection, but I have to pay four different bandits to leave me alone. Even then, I got to ship my ore unsmelted for a hundred miles. If I sent out pure bullion, some other bandit would probably grab it.”

Quoth a third:

“There’s worse than Trini just north of here, up in Tepic. They were capturing people so often that a prominent banker up in Mazatlán was making a regular business of ransoming them. He went down one time with five thousand pesos to buy another fellow’s liberty, and the bandits grabbed him, and held him until his friends sent down five thousand pesos more. So anybody who gets caught now is out of luck. Those fellows have a nasty habit of cutting off your finger each week, and sending it up, all nicely preserved in a bottle of alcohol so it can be recognized, with a little reminder that unless the cash comes pretty soon, they’ll send the head.”

VI

So worthless were the federal troops that many Americans whom I met during my trip professed a preference for bandits.

SO WORTHLESS WERE THE FEDERAL TROOPS THAT MANY AMERICANS PROFESSED A PREFERENCE FOR BANDITS

One, operating a mine in Hidalgo in a town that had never contained a Carranza garrison, had experienced no difficulty at all. Twice he had been visited by members of Pelaez’s gang, and on both occasions the rebels had paid for whatever they took from the company’s stores. When the governor of Hidalgo announced that he was sending troops to guard the mine—for which courtesy the mining company was supposed to pay—the American protested that he needed no troops. The soldiers were sent, despite the protest. On the night of their arrival, the company stores were looted by “bandits.”

While I was in Manzanillo, thieves raided the ranch of Tom Johnson, an American living a few miles south of the port. Among other plunder, they took away five mules. A few days later a Carranzista lieutenant rode up to the ranch-house with the animals, announcing that he had recaptured them, and demanding a reward.

“Reward!” exclaimed Johnson. “Why, you’re being paid by your government to recapture stolen property. I won’t pay you a damned centavo!”

The lieutenant laughed.

“Very well, señor.”

And he rode away, taking the mules with him.

In recognizing Carranza, our State Department had merely created trouble for Americans living in the territory controlled by other leaders.

Several weeks later, in Vera Cruz, I was to meet Dr. Charles T. Sturgis and his wife, who had been held prisoners for many months by Zapatistas in Chiapas. Dr. Sturgis, a retired dentist, had lived a quiet life for years upon his farm in Southern Mexico, practicing his profession gratis among the peons of his neighborhood. One day a party of rebels kidnapped him and his wife, and brought him to the bandit camp on the Rio de la Venta, where they set the Doctor to work on the bandits’ teeth, while Mrs. Sturgis was assigned to labor with the native women. Mrs. Sturgis’ mother, who also had been kidnapped, died after a few weeks. Neither the Doctor nor his wife were young, or robust, yet Cal y Mayor, the Zapatista chieftain, constantly added insult and injury to their toil and privation.

“Why do you go out of your way to hurt us?” Mrs. Sturgis asked him.

“Because your Gringo president has recognized my enemy!” he answered.

For months they remained prisoners. The chieftain used Mrs. Sturgis as a messenger to other bandits, on missions which he considered unsafe for his own men, always holding her husband as hostage for her return. At last, when illness had rendered the Doctor unfit for further work, they were released, with one horse for the two of them, and with only five tortillas as food for their journey of sixty miles through a tropical jungle. When, after six days, they reached their farm, they found that the Carranza government had declared them rebel sympathizers and had confiscated their property. Strange natives were gathering the crops they had sowed. Friends provided funds for their journey to Vera Cruz, where they were to embark for New Orleans. When I met the frail, gray-haired couple in the Vera Cruz consulate, they were on the verge of nervous breakdown.

Yet compared with some Americans, they were fortunate. Many of the stories one picked up at that time were unprintable, particularly those of young girls who fell into bandit hands.

“We went up to Washington,” said one Old-Timer, “with actual photographs of two American women after the rebels were through with them. And those fellows in the State Department just raised both hands and shook their heads, and told us: ‘But such things can’t possibly be true!’”

VII

Everywhere in those days Carranzista generals could be seen disporting themselves in the plaza.

“If they’d get busy, couldn’t they clean up the bandits?” I asked an Old-Timer in Manzanillo.

“Quite likely. But that’s hard work. And they don’t really want to. If they licked all the bandits, the need for so many generals would cease. A general has a pretty good job, you know. Even though he doesn’t get so much salary, he pads his expense account with fodder that the horses never smell, and his payroll with the names of several hundred soldiers that don’t exist.”

He showed me the newspaper account of a battle wherein General Somebody-or-Other with a force of four thousand men, had just defeated Villa in a bloody engagement.

“Now I happened to see the General start on that campaign. He had only two hundred men. And if my suspicion is correct, he never met Villa. It was a lot easier to sit down and write a telegram describing an imaginary victory. The President cited him for distinguished service, and he came home a hero. Carranza does the same thing. Instead of cleaning up the country, he just sends out reports telling the rest of the world that Mexico is now at perfect peace.”

VIII

Eustace and I occupied our enforced sojourn at Manzanillo by writing up the many stories we had gleaned from the Old-Timers, and mailing them home to newspaper editors.

If the American government still insisted most stubbornly in giving Carranza a chance to make good, the American public was waking up. Newspapers were beginning to publish accounts of Mexican outrages upon American citizens and their property. The American press was commencing to expose the Carranza régime.

So many were the stories coming up from Mexico that readers were prepared to believe anything. In fact, they were ready to believe too much. For the news contained in the message we had dispatched upon our arrival in Manzanillo—“Foster and Eustace slain by bandits”—when disseminated by the worthy Mr. Werner, traveled rapidly to the border, and brought back to Manzanillo, from a former associate of mine in Nogales, a telegram inquiring about the details of our death.

Eustace and I regarded the whole affair as a joke.

We wrote my friend a joint letter, explaining that we had merely been captured by Zamorra, and had made our escape from his camp, after having thrashed him and his fellow cut-throats with our bare fists. And when at length the railway resumed operation, and we could resume our journey to Mexico City, we rode away, blissfully ignorant of the future consequences of that absurd letter, rejoicing that Manzanillo was a horror of the past. Having attacked President Carranza consistently in all our newspaper articles, we were eager to visit his capital to learn whether he were really so bad as we had pictured him.