CHAPTER VIII

THE MEXICAN CAPITAL

I

It was another four days’ journey to Mexico City—a journey directly eastward and a trifle skyward.

Mexico is a mountainous country—so loftily mountainous that one has only to travel upward to pass in turn through every variety of climate and every type of landscape.

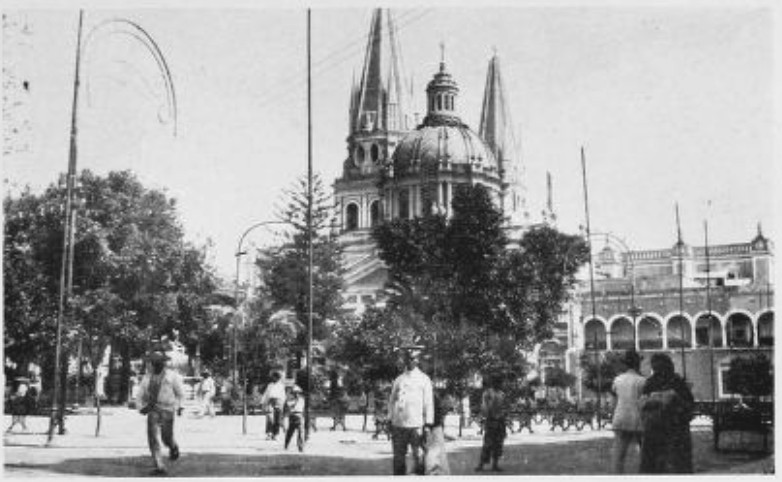

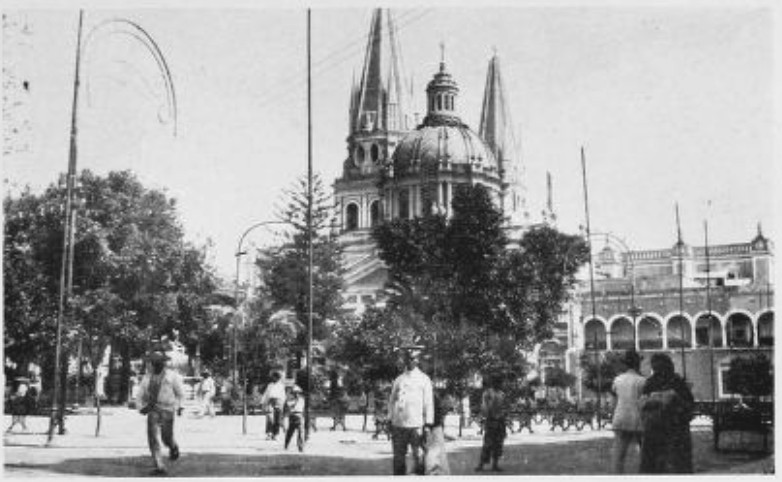

The road led from Manzanillo through the hot coastal plain—through palm-land and swamp-land where sweating, semi-naked peons waded knee-deep in pools formed overnight by the first downpour of a tropic rainy season—to Colima, a conventional little city at the base of a snow-tipped volcano—into the highlands through tortuous defiles where the cane gave way to maize and the jungle-growth to cactus—past tiny villages of adobe huts clustering about a huge white church that dwarfed the rugged gullies—into a climate of eternal spring—to Guadalajara, the second largest and the most delightful city of the republic, where orange trees were golden throughout the year—and beyond, to the wide expanses of Mexico’s high plateau—to a land of vast, gloomy spaces and lonely grandeur—the grandeur of rolling yellow plains stretching to a distant horizon rimmed with jagged peaks, where at twilight the purple shadows crept upward toward an azure sky—to a country desolate and superb, and a trifle wintry.

THE ORANGE TREES IN GUADALAJARA’S PLAZA WERE GOLDEN THROUGHOUT THE YEAR

To the stay-at-home American, Mexico is only a sun-scorched desert. In reality, it is a land of everything—of sandy wastes, of rugged mountains, of rank tropical jungles, of temperate valleys—of lowlands bathed in moist tropic heat, of midlands where strawberries are always ripe, even of highlands swept eternally by chilling winds. Yet always there is some intangible spirit about it that makes it unmistakably Mexico, especially upon the bleak plateau.

II

The haunting melancholy of the high altitude seemed to have affected the natives.

Below, on the coast, the poverty-stricken Indians had appeared contented and happy. On the tableland they were very solemn. A peon marching behind his little burro wore the same stolid, pack-animal expression as the beast itself. There was no animation in the faces. The greater part of the masculine population sat upon the station platforms, wrapped in blankets and meditation, waiting only for another day to pass.

The women, more energetic than the men, still besieged the car windows, offering for sale the local products, not in the cheery manner of the lowland women, but hopelessly and mournfully, as though they expected that no one would buy. Unimaginative as the men-folks, they all sold the same article—whatever article some more energetic ancestor, many years before, had sold in their particular village. At Irapuato it was strawberries; at Celaya a species of fudge in tiny wooden boxes; at Queretaro opals from the neighboring mines; at San Juan del Rio lariats and ropes.

They waited in a bedraggled group as the train pulled in. They all advanced toward the same window. When the first customer did not buy, they shrugged their shoulders and turned away. Gradually it would dawn upon them that there were other passengers, and they would drift out along the sides of the other cars, holding up their baskets in mute appeal.

“It is pulque,” explained a Mexican fellow-passenger. “They are all sodden with it here. Que borachos! What drunkards!”

Pulque, the cheap liquor of the plateau, grows only in the highlands, and sours too quickly to be transported elsewhere. As we ascended toward the 7500-foot altitude of the capital, fields of maguey—the source of the beverage—became more and more frequent until they lined the railway in long even rows that covered the rolling plains to the distant mountain-rim—each cactus resembling a huge blue artichoke, and adding another touch of color to the landscape. In blossoming, the plant sends up a tall stalk from which, if it be tapped, there flows a milky fluid locally known as “aguamiel” or “honey-water,” which ferments very rapidly. Within a few hours it becomes a mild intoxicant with a taste like that of sour buttermilk; within a few hours more it becomes a murder-inspiring poison with a taste which the most profane of mortals could never adequately describe.

In the fields peons could be seen, each with a pigskin receptacle slung over his back, trotting from plant to plant, climbing upon the pulpy leaves of the big cactus as though he were some little bug crawling into a flower, bending over the central pool to suck the liquid into a hollow gourd, and discharging it into the pigskin sack. When the bag was filled, he would trot away to the hacienda with it; a little stale pulque would start it fermenting; on the morrow a series of early trains, the equivalent of the milk trains elsewhere, would carry it to all the neighboring cities to befuddle the population there.

Drunkenness is extremely common in Mexico. Although pulque can not be widely distributed, the Mexicans boil the lower leaves of their cactus and distill therefrom their mescal and tequila—two fiery alcoholic stimulants condemned both by moralists and by connoisseurs of good liquor—which are responsible for most of the acts of violence which transpire in the republic. Yet drunkenness is most prevalent in the highlands, for pulque, while comparatively mild, is the cheapest thing in Mexico, and one can buy a quart or two for a few pennies.

On each station platform the men sat patiently, waiting while the women offered their wares. The old girl probably would not make a sale, but quién sabe? If she did, there would be more money for pulque. Already sodden with it, they wrapped their tattered blankets about them, and watched fatalistically, inhabitants of the world’s richest country, resigned to an empty life, oblivious to the charm of the most fascinating country on all the earth.

For despite its gloom, I know of no country more fascinating than the Mexican plateau.

In the clear mountain air each picturesque detail of the vast landscape stood out distinctly—the peaked hat of a little Indian plodding solemnly behind his burro—a herd of cattle grazing leisurely upon the coarse bunch-grass, mere brown specks against the yellow hills—a lonely white chapel with two slender towers and a massive dome, standing by itself without the suggestion of a possible worshiper within miles and miles—an infrequent hacienda with a host of tiny laborers’ shacks grouped about a crumbling ranch-house that once had been a palace. Yet the indefinable charm of the scene lay not in the details, but in the immensity of the canvas. Against the majestic sweep of the wasteland itself, the details appeared dwarfed and isolated. They gave one a feeling of utter loneliness—even of sadness—a strangely delicious sadness. A bleak, gloomy place was this plateau, yet many years hence, whenever one heard “Mexico,” one would think not of the desert or the jungle, but of these vast stretches of yellow wasteland and this horizon of purple mountains, and one would sense a haunting desire to see them again.

III

After two days upon that plateau, Mexico City was a shock.

The train roared into a crowded station. Vociferous hotel runners burst into the car and fought up and down the aisles. Cargadores clamored outside the windows. Mexican friends met Mexican friends with loud cries of joy. All screamed noisily to make themselves heard above the din of claxons from riotous streets outside.

Some runner, having driven rivals away from Eustace and myself, handed our suit-cases through the window to a waiting desperado, and we chased him frantically through the mob. Some chauffeur, having driven rivals away from the suit-cases, packed them inside a taxi, shoved us in after them, and shot away at full speed the moment his assistant cranked the car, leaving the assistant to dodge aside and jump aboard as best he could, zigzagging madly through a fleet of other taxis, all of which were shrieking their claxons and roaring past with wide open cut-out, avoiding a dozen clanging trolley cars and scraping along the side of a thirteenth, pausing momentarily while a rabid policeman waved his arms and screamed abuse in voluble Spanish, then tearing onward as wildly as before through a world of leaping pedestrians.

We drew up with a grinding of brakes before a modern hotel, the chauffeur collected a modern fare, a hotel clerk grunted at us with modern incivility, a bell-hop conducted us with modern condescension to a modern room, and left us to spend a night of modern wakefulness listening to the nerve-wracking din of a thoroughly modern city outside.

After the plateau, it seemed profane. One had the illusion that in the midst of a grand cathedral service the bishop had given a college yell, the organ had burst into jazz, and the choir had danced an Irish jig.

IV

In the morning Eustace and I wrote President Carranza a friendly little note, requesting an interview. Then we set out to see the town.

It proved surprisingly attractive by daylight—one of the most ornate in the Western Hemisphere outside of Argentina or Brazil. If it lacked the impressive solidity of an American city, and failed to startle with giant sky-scrapers, it undoubtedly surpassed New York or any other Yankee metropolis—including Washington—in the beauty of its parks and boulevards.

MEXICO CITY, ONE OF THE MOST ORNATE CAPITALS IN THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE, SOMEWHAT RESEMBLED PARIS

Superficially it suggested Paris. Along the streets of its business section the buildings, all of the same height of three or four stories, were of European architecture. Its avenues and gardens, with their numerous statues and monuments, were distinctly French. There was a suggestion also of other lands. There were German beer halls and rathskellers, dignified English banks, Italian restaurants, and Japanese curio shops. There was even the American quick-lunch counter where a darky from Alabama asked abruptly, “What’s yours, boss?” and shouted “One ham sandwich!” through a wall-opening to a white-capped cook. But French window-displays of modes and perfumery predominated, and combining with the architecture, gave the city the general aspect of Paris.

V

It proved a cool city, however, both in climate and manners. Of the two, the former seemed the more kindly. If the air were chilly at morning or evening—either in summer or winter, wherein there is little variation—it was hot enough at mid-day to bring out the perspiration. But the manners remained constantly those of all large cities, even in Mexico.

There was no reason that they should be otherwise. After traveling, nevertheless, through smaller towns, where natives looked upon a newcomer with interest and other Americans immediately introduced themselves, we found that we were regarding the entire population of the capital as downright discourteous. Americans upon the street were not merely indifferent but suspicious. When we attempted to stop one to inquire the way to the National Museum, he would duck aside and hurry away before we could speak. We had about decided to punch the next fellow-countryman we met, and were looking for a small one, when we discovered the reason for American distrust.

Every fourth gringo in town seemed to be broke and in need of alms.

Two clean-cut youngsters, lured here evidently by the illusion that any one could make his fortune in Latin America, came into an American restaurant where we lunched, and begged the proprietor for a job washing dishes.

“For God’s sake, man, we’re hungry! And we’re willing to work! All we ask is our meals, and five pesos a week to cover room rent—not a penny more!”

The proprietor shook his head.

“I’m sorry for them,” he said, as the youths went out, “but there’s too many. They use up all your sympathy.”

Another youth stopped us in the park.

“I’m not a regular bum,” he pleaded. “I came down here because a fellow I knew invited me. He was a Mexican, and he worked beside me in the auto factory up at Detroit. He was always telling me what a fine country this was. After he went home, he kept writing to me about how when I came to Mexico his house would be my house. I thought he meant it. And he kept saying there were lots of jobs. I didn’t know it was their habit to say nice things like that just to please you. I came down here three weeks ago, and there were no jobs—or else Mexicans took them on a salary that wouldn’t support an American—and when I looked up my friend, he kept saying that his house was my house, but I’ve never seen the inside of it, and since the first day I haven’t seen him. I’ve spent my last cent, and I’m up against it.”

But among the down and out were many less deserving, with stories just as good. Some were draft-evaders that had come to Mexico during the War, and had been unable to return. Others were professional vagabonds who had gravitated southward to enjoy the privileges of a country that recognized vagrancy as a legitimate profession. At first, like most new arrivals touched by the pitiful sight of a fellow-countryman in misfortune in a foreign land, we gave liberally. But within a few days, we grew hardened, and like the Old-Timers, we ducked away at the very approach of a strange American, even though he merely wished to ask his way to the National Museum.

For companionship, we confined ourselves to Old Barlow, who occupied the hotel room next to ours, and who drifted into our quarters now and then to gratify an Old Resident’s love of spinning yarns.

He was somewhat of a pessimist. He liked Mexico but he always carried a gun. A gray-haired man, walking with a slight limp, he claimed to have been present at every earthquake, revolution, and dog-fight that had ever transpired in Mexico or Central America, and when once started on a recital, each murder suggested another.

“Best thing I ever did see was the duel Cash Bradley fought. Cash didn’t know nothing about swords, so when this geezer challenged him, he went up to ask General Agramonte for advice. Great old war-horse was Agramonte! Says he, ‘You don’t need to know nothing about swords—except one little trick of swordsmanship I’m going to teach you. When you first start, the seconds will count three, and at each count you bring down your sword and clash it politely with the other guy’s sword by way of salute. Well, on the count of three, you just accidentally miss the other fellow’s sword and salute him politely in the neck.’ And believe me, boys, that little feat of swordsmanship just saved Cash Bradley’s life.”

Then he would puff at his pipe, and muse a while.

“Great old war-horse, Agramonte! I remember when he had a run-in with President Huerta, the bird Carranza chased out. Huerta invited him up to the Palace for tea, and when Agramonte was about to leave, he says to him, ‘I’ve got forty soldiers on the staircase, waiting to shoot you on your way home.’ Agramonte didn’t blink an eyelash. He just shoved his own gun into Huerta’s ribs, and answers, ‘Then you’ll come with me, and if one soldier raises a gun, you’ll die first.’ They walked down the staircase, arm in arm, and kissed each other good-by at the door, and not a soldier fired a shot.”

Then he would muse again, rapturously, as though recalling pleasant memories.

“Huerta was some war-horse himself. He used to be a general in Madero’s army, until he suddenly walked into the Palace, with his army behind him, and told Madero to quit. Huerta was always a great stickler for constitutionality, so he wanted Madero to sign a proper resignation. And Madero wouldn’t resign. Huerta heated the poker and started to tickle him with it. You could see the blood running out of Madero’s eyes, but he was stubborn as a mule, and he just kept saying, ‘I’m the rightful president of Mexico!’ Finally Huerta had to shoot him. But he was a great stickler for constitutionality, so he put Madero’s body in a coach, and took it out for a ride and had his troops fire a volley on the coach; then he told the world that Madero was shot by his own men while fleeing the country. Some one had to take the presidency then, so Huerta took it. Great stickler for constitutionality was Huerta!”

Another puff at his pipe.

“Carranza don’t do his own shooting, but he’s got plenty of generals to do it for him. If I was you boys, and had written some nasty things about the Old Gent, like you say you have, I wouldn’t wait for no interview. I’d take the next train to Vera Cruz, and catch a boat.”

VI

We waited for the interview. The chances were that nothing we had written would ever be published. If it were, Carranza would never know it. And there was more of Mexico City to be seen.

If it bore a superficial resemblance to Paris, its population remained distinctly Mexican.

In the early morning, upon the Avenida Francisco I. Madero, the Mexican Fifth Avenue, the boulevardiers were mostly Indians in blankets, and shop girls hurrying to work with black shawls over their heads. Gradually they gave way to people in European dress, yet here and there in the crowd there passed an hacendado just in from his country estate and still wearing riding boots and sombrero and a huge revolver pendant from a heavy leather belt encircling his ample girth. Then came the shoppers—stout, overpowdered matrons with a flock of señoritas in tow—all in Parisian garb, but unmistakably Mexican. They came in handsome private cars, alighting with the assistance of uniformed attendants, and disappearing into the fashionable modistes’ establishments with the grand aristocratic air of the newly rich—for most of the city’s real aristocracy had fled the country during the long series of revolutions, and these were largely the wives and daughters of the successful generals.

At noon, the streets became almost deserted, for here as everywhere the siesta was a ritual, but later the crowd reappeared, and now for a brief hour the Avenida did bear some true resemblance to Paris. The womenfolk came out in their new finery, and rolled up and down in their handsome cars to display themselves. The men, having finished the day’s work, loitered along the sidewalk, chatting merrily, twiddling their canes, puffing at their cigarettes, and keeping an attentive eye on passing femininity. But at twilight, the womenfolk disappeared, and the chill of evening brought an end to the atmosphere of gayety. The men still loitered, but the attentive eye was fixed now upon the shop girls that hurried homeward.

“Why hasten, chiquita?” they called after each mantilla-muffled figure. “Come with me instead.”

Sometimes the male voices were serious. Usually they were casual, as though merely performing the rite—considered a sacred duty by the men of all Latin America—of insulting the unchaperoned woman. The girls were accustomed to it, and paid no attention either to the words or to the nudges and pinches that followed. Now and then there passed a street-walker—an institution seldom seen in the smaller Mexican cities, where vice is more carefully segregated—and she invited with a concentrated flash of eyes, but she did not speak, as might her counterpart in Paris. Over the crowded streets there hung an air of gravity—of Mexican gravity—the gravity of the high plateau.

Darkness came. The men pulled up their coat collars, pulled in their necks, and discussed the advisability of a cocktail. Lights appeared in thick clusters of glowing bulbs, as in the French capital, but they shed a radiance that inspired no gayety. The taxis still roared and rattled, and shot zigzag through the streets like so many skating-bugs on a millpond; the trolleys passed at thirty-foot intervals incessantly clanging their gongs; the policemen at each corner turned their “Alto-Adelante” or “Go-Stop” signs first one way, then another, blowing their shrill whistles first with one toot, then two toots, and sending the traffic scurrying first in one direction, then another; above the Avenida there rose the grand discord of a busy metropolis; yet Mexico City became merely noisy rather than lively. Acquaintances embraced acquaintances demonstratively, yet with an air of conventionality. The loitering throngs before the blazing doorways of theaters or cinemas were subdued and solemn. The street-walkers invited with unsmiling eyes. The boulevardiers withdrew, group by group, for their cocktails, not to pleasant sidewalk cafés like those of Paris, but to formal Spanish bar-rooms. By ten o’clock the sidewalks were almost as empty as those of Hermosillo. Only the flying taxis remained, dashing about with screeching claxons as though crying vainly, “This is Paris.”

It looked like Paris, and from a distance it sounded like Paris, but the Parisian insouciance was missing. This was still Mexico—the Mexico of the high plateau.

VII

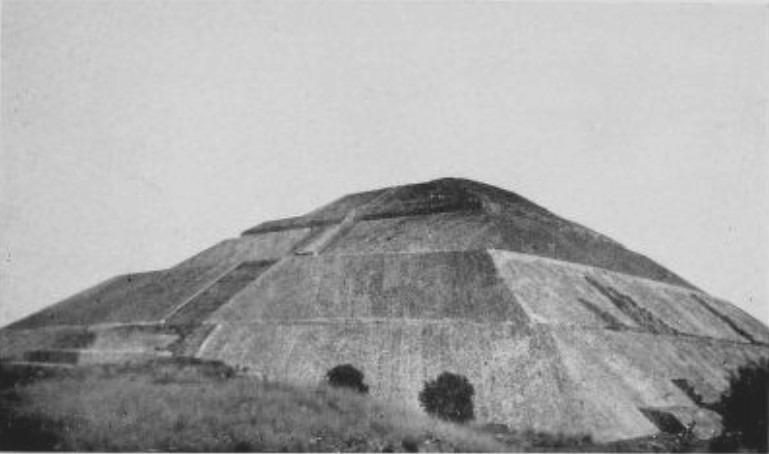

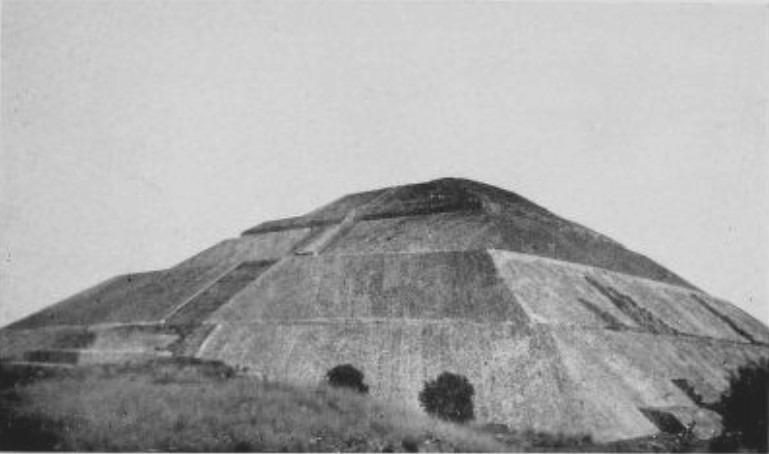

Carranza not proving very prompt in answering his correspondence, we amused ourselves with a visit to the ancient pyramids of San Juan Teotihuacán—remnants of what had been a mighty empire before the Conquest—distant some twenty-eight miles from the Capital.

A leisurely train carried us there in something over an hour and a half. We descended at the station, expecting to be pounced upon by a dozen professional guides, but none molested us. Little barefoot children with spurious relics were our only assailants. We looked about for a conveyance and discovered the Toonerville Trolley. An individual asleep inside acknowledged that he was the conductor. He proved also to be the motorman, for having collected our fare, he aroused the mule, and the car jogged slowly away with swaying gait through lanes of cactus, toward the squatty figures of two pyramids, deceitfully small with distance and dwarfed by the mountains behind them.

But at length the cactus-hedge ceased, and upon our right appeared the ruins of a temple—the Temple of Quetzacoatl—a big square surrounded by heavy ramparts of earth and stone, wherein a group of workmen were restoring a wall lined with monster demon-heads and gargoyles carved of solid rock. And a few minutes later we were at the foot of the pyramids, no longer small and dwarfed, but looming skyward above us—pyramids which, if less imposing in stature than those of Egypt, excel them in the dimensions of their base, and may even antedate them, according to the estimates of some archeologists, by possibly a thousand or two thousand years.

THE MEXICAN PYRAMIDS PROBABLY ANTEDATE THOSE OF EGYPT BY A THOUSAND YEARS OR MORE

Speculation as to just how old they really are has kept many a scientist out of worse mischief, but seems to have accomplished little else. Thanks to the demolition by the fanatical Spaniards of the heathen writings they found in the Americas, practically nothing is known of their origin. It is believed that they antedate the Toltecs, and that they testify to the existence of an ancient race in Mexico, long since vanished to who-knows-where, that once surpassed in engineering skill and presumably in civilization the early peoples of the other Hemisphere.

So little had we read of them, and so free did they appear from exploitation as a tourist sight, that Eustace and I experienced almost the joy of personal discovery. But it was soon rudely shattered. For up drove an automobile from Mexico City’s leading hotel, and out climbed two other Americans.

They were recognizable immediately as Rotarians. They were both good fellows. They had met at the Regis, and in talking over business had discovered that both by profession were Realtors. They had found a mutual bond of interest in the fact that Mexico City, although it was a better burg than they had anticipated, had a less up-to-date garbage-disposal system than Long Branch, N.J., or Newburyport, Mass. They were now having a whale of a time kidding the guide good-naturedly about the shortcomings of his country, and were getting to like each other better every minute. Next week, upon their return home, each would tell his friends about the good scout he bumped into down in Mexico, and would exclaim, “It beats all how you meet people! The world’s a pretty small place after all!” And at Christmas, each would send the other a card playfully addressed “Senor.”

“So that’s what you brought us out here to see!” said the man from Long Branch.

The other drew out a guide-book and read:

“The pyramid of the Sun Tonatiuh Itzcuatl damn this language anyhow a truncated artificial mound 216 feet high by about 721 and 761 feet at the base divided into five pyramidal sections or terraces which narrow as they ascend. Now that we’ve seen that, where do we eat?”

We left them below while we started up the long flight of stone steps that led up the five terraces of the larger pyramid, The Sun. It had been partially restored, and its surface of many-colored rocks, each the size of a domesticated cobblestone, originally held together with adobe, now gleamed white with Portland Cement. Upon its lofty top, covered to-day by a flat rock, there had once been a gigantic statue of the Sun, cut from a block of porphyry, and ornamented with gold. And here the Aztec priests had probably plunged their arms into many a victim’s breast, to draw out a beating heart, and toss the body of the sacrifice down the steep rocky sides to the wasteland beneath.

It was very quiet now, with the restful calm that one finds only upon a mountain-top. One could look down upon miles and miles of rolling plain dotted with cactus of many shades of green, clustering sometimes in prickly forests, stretching away in two parallel lines to mark a trail, arranging themselves in military rows to indicate a pulque hacienda, gathering in a hedge about the low flat roof of an adobe homestead. Here or there rose the unfailing spires and dome of another lonely church. In the fields a yoke of oxen, plowing a cornfield, seemed scarcely to move. The sky above was of vivid blue, with puffy white clouds along the horizon. Sounds drifted up from the world below—the mooing of a cow, the cackle of a hen, the tap of a hammer—each very distinct, yet so softened by distance that it seemed not to interrupt the silence—as though it merely came from a far-away land wherewith one had severed connection.

Then the two tourists came panting up the steps.

“Damn those stairs, anyway. They ought to have a railing on each side.”

Eustace blandly suggested an elevator, but the sarcasm was lost.

“We’d have one, if this was in Newburyport. We’d have a regular train service out here, and we’d put in a modern cafeteria. Boy, but you could make money out of this thing, if you had it in the United States! You could hire a bunch of Irishmen and dress them up like Aztecs, have a couple of girls doing an Indian dance on top, charge a fifty-cent admission—why, man, you’d clean up a fortune!”

As we started down to catch the evening train back to the taxi-screeching City of Mexico, Babbitt and Kennicott were carving their initials on the flat rock atop the Pyramid of the Sun.

VIII

A week drifted past, and Sunday arrived.

On that, of all days, Mexico City was most typically Mexican.

The aristocrats paraded themselves in the parks; the middle-classes went picnicking; the peons went to church.

We strolled out along the Avenida Madero, past the National Opera House—said to be the handsomest building of its kind on the continent, but still with an unfinished dome because one administration had started it, and others had neglected to provide funds for its completion. Beyond it lay the Alameda, the Mexican Central Park. It was a European park, quite unlike the palm-grown plazas of the smaller cities, but there was the usual Mexican band concert, and the people were renting camp-chairs along the shady walks to enjoy the national pastime of seeing and being seen.

Beyond the Alameda, commenced a wide boulevard, the Paseo de la Reforma, typically Parisian in its wealth of monuments, and lined with handsome embassies and residences, leading out to Chapultepec, a larger and even more charming park, with wide expanses of lawn and woodland and lake and meadow surrounding the National Palace, a squatty fortress-like structure pleasing in its effect of strength and beauty, perched upon high cliffs and glimpsed through the tree-tops as though it hung suspended in the sky. The policemen here were clad in Mexico’s charro costume—the costume of the old grandees—with short buff jacket, skin-tight blue trousers lined with rows of silver buttons, flowing red tie, huge velvet sombrero, and a big gleaming sword. An orchestra in similar costume held forth beneath an awning near the lake, playing sweetly upon a marvelous combination of guitars, mandolins, marimbas, harps, cellos, oboes, and what not. Automobiles rolled past along the winding driveway, each filled with a bevy of señoritas. Horsemen rode grandly past, dressed also in charro costume, and mounted upon the finest steeds in Mexico. Pedestrians idled beside the lake, watching the procession, and listening to the orchestra, with that rare enjoyment of really good music that characterizes peon and aristocrat alike. Here, as in the small-town plaza, the Mexicans were finding a pleasure in their park such as no American ever finds in the parks of the United States. Here, as everywhere in Mexico,