CHAPTER II

BANDITS!

I

I crossed the border at daybreak.

In the manner of a Gringo who first passes the Mexican frontier, I walked cautiously, glancing behind me from time to time, anticipating hostility, if not actual violence.

In the dusk of early morning the low, flat-roofed adobe city of Nogales assumed all the forbidding qualities of the fictional Mexico. But the leisurely immigration official was polite. The customs’ inspector waved me through all formalities with one graceful gesture. No one knifed me in the back. And somewhere ahead, beyond the dim line of railway coaches, an engineer tolled his bell. The train, as though to shatter all foreign misconceptions of the country, was about to depart on scheduled time!

II

Somewhat surprised, I made a rush for the ticket window.

A native gentleman was there before me. He also was buying passage, but since he was personally acquainted with the agent, it behooved him—according to the dictates of Spanish etiquette—to converse pleasantly for the next half hour.

“And your señora?”

“Gracias! Gracias! She enjoys the perfect health! And your own most estimable señora?”

“Also salubrious, thanks to God!”

“I am gratified! Profoundly gratified! And the little ones? When last I had the pleasure to see you, the chiquitita was suffering from—”

The engineer blew his whistle. A conductor called, “Vamonos!” I jumped up and down with Gringo impatience. The Mexican gentleman gave no indication of haste. The engineer might be so rude as to depart without him, but he would not be hurried into any omission of the proper courtesies. His dialogue was closing, it is true, but closing elaborately, still according to the dictates of Spanish etiquette, in a handshake through the ticket window, in an expression of mutual esteem and admiration, in eloquent wishes to be remembered to everybody in Hermosillo—enumerated by name until it sounded like a census—in another handshake, and finally in a long-repeated series of “Adios!” and “Que le vaya bien!”

What mattered it if all the passengers missed the train? Would there not be another one to-morrow? This, despite the railway schedule, was the land of “Mañana.”

III

On his first day in Mexico, the American froths over each delay. In time he learns to accept it with fatalistic calm.

As it happened, the dialogue ceased at the right moment. Every one caught the train. Another polite Mexican gentleman cleared a seat for me, and I settled myself just as Nogales disappeared in a cloud of dust, wondering why any train should start at such an unearthly hour of the morning.

The reason soon became obvious. The time-table had been so arranged in order that the engineer could maintain a comfortable speed of six miles an hour, stop with characteristic Mexican sociability at each group of mud huts along the way, linger there indefinitely as though fearful of giving offense by too abrupt a departure, and still be able to reach his destination—about a hundred miles distant—before dark.

In those days—the last days of the Carranza régime—trains did not venture to run at night, and certainly not across the Yaqui desert. It was a forbidding country—an endless expanse of brownish sand relieved only by scraggly mesquite. Torrents from a long-past rainy season had seamed it with innumerable gullies, but a semi-tropic sun had left them dry and parched, and the gnarled greasewood upon their banks drooped brown and leafless. Even the mountains along the horizon were gray and bleak and barren save for an occasional giant cactus that loomed in skeleton relief against a hot sky.

IN THOSE DAYS TRAINS DID NOT VENTURE TO RUN AT NIGHT ACROSS THE SONORA DESERT

This was the State of Sonora, one of the richest in Mexico, but its wealth—like the wealth of all Mexico—was not apparent to the eye of the tourist. The villages at which we stopped were but groups of low adobe hovels. The dogs that slunk about each habitation, being of the Mexican hairless breed, were strangely in harmony with the desert itself. And the peons—dark-faced semi-Indians, mostly barefoot, and clad in tattered rags—seemed to have no occupation except that of frying a few beans and selling them to railway passengers.

At each infrequent station they were awaiting us. Aged beggars stumbled along the side of the coach, led by tiny children, to plead in whining voices for “un centavito”—“a little penny”—“for the love of God!” Women with bedraggled shawls over the head scurried from window to window, offering strange edibles for sale—baskets of cactus fruit resembling fresh figs—frijoles wrapped in pan-cake-like tortillas of cornmeal—legs of chicken floating in a yellow grease—while the passengers leaned from the car to bargain with them.

“What? Fifteen centavos for that stuff? Carramba!”

“Ten cents then?”

“No!”

“How much will you give?”

Both parties seemed to enjoy this play of wits, and when, with a Gringo’s disinclination to haggle, I bought anything at the price first stated, the venders seemed a trifle disappointed. Everybody bought something at each stopping-place, and ate constantly between stations, as though eager to consume the purchases in time to repeat the bargaining at the next town. The journey became a picnic, and there was a child-like quality about the Mexicans that made it strangely resemble a Sunday-school outing at home.

Although an escort of Carranzista soldiers occupied a freight car ahead as a precaution against the bandits which infested Mexico in those days, the passengers appeared blandly unconcerned.

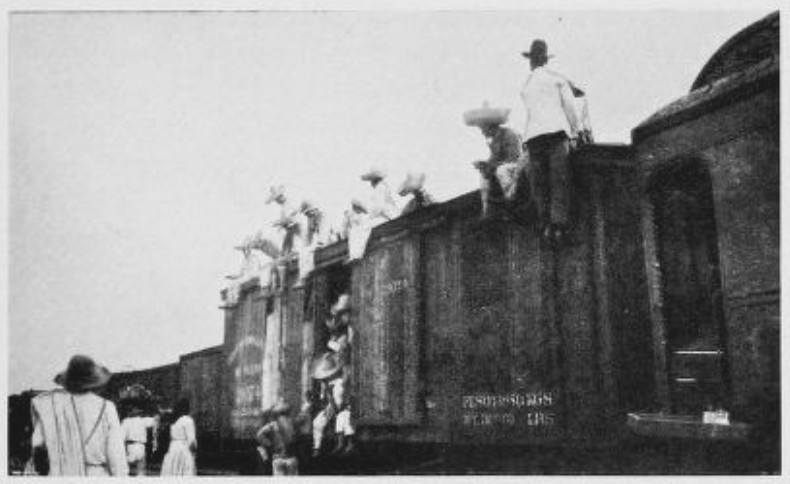

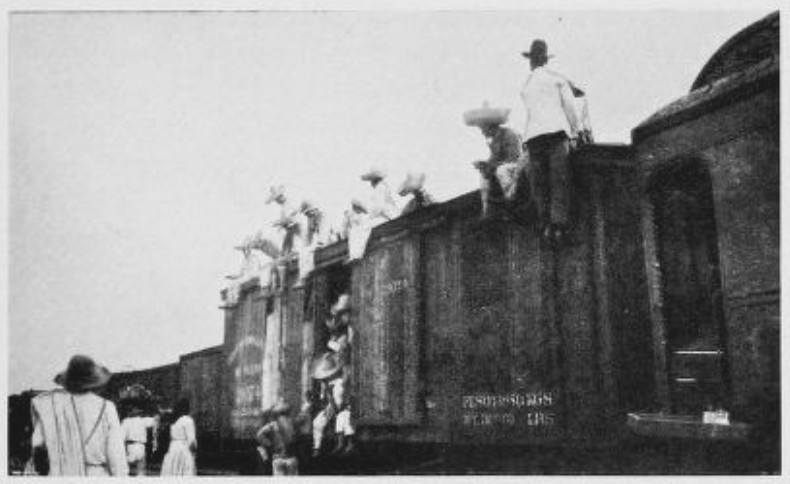

AN ESCORT OF SOLDIERS OCCUPIED A FREIGHT CAR AHEAD AS A PRECAUTION AGAINST BANDITS

Each removed his coat, and lighted a cigarette. From the car wall a notice screamed the Spanish equivalent of “No Smoking,” but the conductor, stumbling into the coach over a family of peons who had crowded in from the second-class compartment, merely paused to glance at the smokers, and to borrow a light himself. Every one, with the friendliness for which the Latin-American is unsurpassed, engaged his neighbor in conversation. The portly gentleman who had cleared a seat for me inquired the object of my visit to Mexico, and listened politely while I slaughtered his language. The conductor bowed and thanked me for my ticket. When the peon children in the aisle pointed at me and whispered, “Gringo,” their mother ceased feeding a baby to “Shush!” them, their father kicked them surreptitiously with a loose-flapping sandal, and both parents smiled in response to my amused grin.

There was something pleasant and carefree about this Mexico that proved infectious. Atop the freight cars ahead, the escort of federal troops laid aside their Mausers, removed their criss-crossed cartridge-belts, and settled themselves for a siesta. As the desert sun rose higher, inducing a spirit of coma, the passengers also settled themselves for a nap. The babble of the morning gave place to silence—to silence broken only by the fretting cry of an infant and the steady click of the wheels as we crawled southward, hour after hour, through the empty wastes of mesquite.

And then, as always in Mexico, the unexpected happened.

The silence was punctured by the staccato roar of a machine-gun!

IV

In an instant all was confusion.

Whether or not the shooting came from the Carranzista escort or from some gang of bandits hidden in the brush, no one waited to ascertain. Not a person screamed. Yet, as though trained by previous experience, every one ducked beneath the level of the windows, the women sheltering their children, the men whipping out their long, pearl-handled revolvers. The only man who showed any sign of agitation was my portly friend. His immense purple sombrero had tumbled over the back-rest onto another seat, and he was frantic until he recovered it.

After the first roar of the machine-gun, all was quiet. The fatalistic calm of the Mexicans served only to heighten the suspense. The train had stopped. When, a few months earlier, Yaqui Indians had raided another express on this same line, the guard had cut loose with the engine, leaving the passengers to their Fate—a Fate somewhat gruesomely advertised by a few scraps of rotted clothing half-embedded in the desert sand. The thought that history had repeated itself was uppermost in my mind, and the peon on the floor beside me voiced it also, in a fatalistic muttering of:

“Dios! They have left us! We are so good as dead!”

We waited grimly—waited interminably. With a crash, the door opened. A dozen revolvers covered the man who entered. A dozen fingers tightened upon a trigger. But it was only the conductor.

“No hay cuidado, señores,” he said pleasantly. “The escort was shooting at a jack-rabbit.”

V

The passengers sat up again, laughing at one another, talking with excited gestures as they described their sensations, enjoying one another’s chagrin, all of them as noisy and happy as children upon a picnic. They bought more frijoles, and the feast recommenced, lasting until mid-afternoon, when we pulled into Hermosillo, the capital of Sonora.

A swarm of porters rushed upon us, holding up tin license-tags as they screamed for our patronage. Hotel runners leaped aboard the car and scrambled along the aisle, presenting us with cards and reciting rapidly the superior merits of their respective hostelries, meanwhile arguing with rival agents and assuring us that the other fellow’s beds were alive with vermin, that the other fellow’s food was rank poison, and that the other fellow’s servants would at least rob us, if they did not commit actual homicide.

I fought my way through them to the platform, where another battle-scene was being enacted.

Mexican friends were meeting Mexican friends. To force a passage was a sheer impossibility. Two of them, recognizing each other, promptly went into a clinch, embracing one another, slapping one another upon the back, and venting their joy in loud gurgles of ecstasy, meanwhile blocking up the entire platform.

Restraining Gringo impatience once more, I stood and laughed at them. In so many cases the extravagant greetings savored of insincerity. One noticed a flabbiness in the handclasps, a formality in the hugs, an affectation in the shouts of “Ay! My friend! How happy I am to see you!” Yet in many cases, the demonstrations were real—so real that they brought a peculiar little gulp into one’s throat, even while one laughed.

Be they sincere or insincere, I already liked these crazy Mexicans.