CHAPTER III

IN SLEEPY HERMOSILLO

I

A little brown cochero pounced upon me and took me aboard a dilapidated hack drawn by two mournful-looking quadrupeds.

“Hotel Americano?” he inquired.

“No. Hotel distinctly Mejicano.”

He whipped up his horses, and we jogged away through narrow streets lined with the massive, fortress-like walls of Moorish dwellings, past a tiny palm-grown plaza fronted by an old white cathedral, to stop finally before a one-story structure whose stucco was cracked and scarred, and dented with the bullet holes of innumerable revolutions.

The proprietor himself, a dignified gentleman in black, advanced to meet me. Were there rooms? Why not, señor? Whereupon he seated himself before an immense ledger, to pore over it with knitted brows, stopping now and then to stare vacantly skyward in the manner of one who solves a puzzle or composes an epic poem.

“Number sixteen,” he finally announced.

“Occupied,” said a servant.

Another period of intellectual absorption.

“Number four.”

There being no expostulation, a search ensued for the key. It developed that Room Number Four was opened by Key Number Seven, which—in conformity to some system altogether baffling to a Gringo—was usually kept on Peg Number Thirteen, but had been misplaced by some careless servant. The little proprietor waved both hands in the air.

“What mozos!” he exclaimed. “No sense of orderliness whatsoever!”

A prolonged search resulted, however, in its discovery, and the proprietor himself led the way back through a succession of patios, or interior gardens, the front ones embellished with orange trees, and the rear ones with rubbish barrels, to Room Number Four, from which the lock had long ago been broken.

It was a large apartment, with brick floor. It contained a canvas cot, a wobbly chair, and an aged bureau distinguished for its sticky drawers, an air of lost grandeur, and a burnt-wood effect achieved by the cigarette butts of many generations of guests. The bare walls were ornamented only by a placard, containing a set of rules—printed in wholesale quantities for whatever hotels craved the enhanced dignity of elaborate regulations—proclaiming, among other things, that occupants must comport themselves with strict morality.

“One of our very choicest rooms, señor,” smiled the proprietor, as he withdrew. “It has a window.”

A window did improve it.

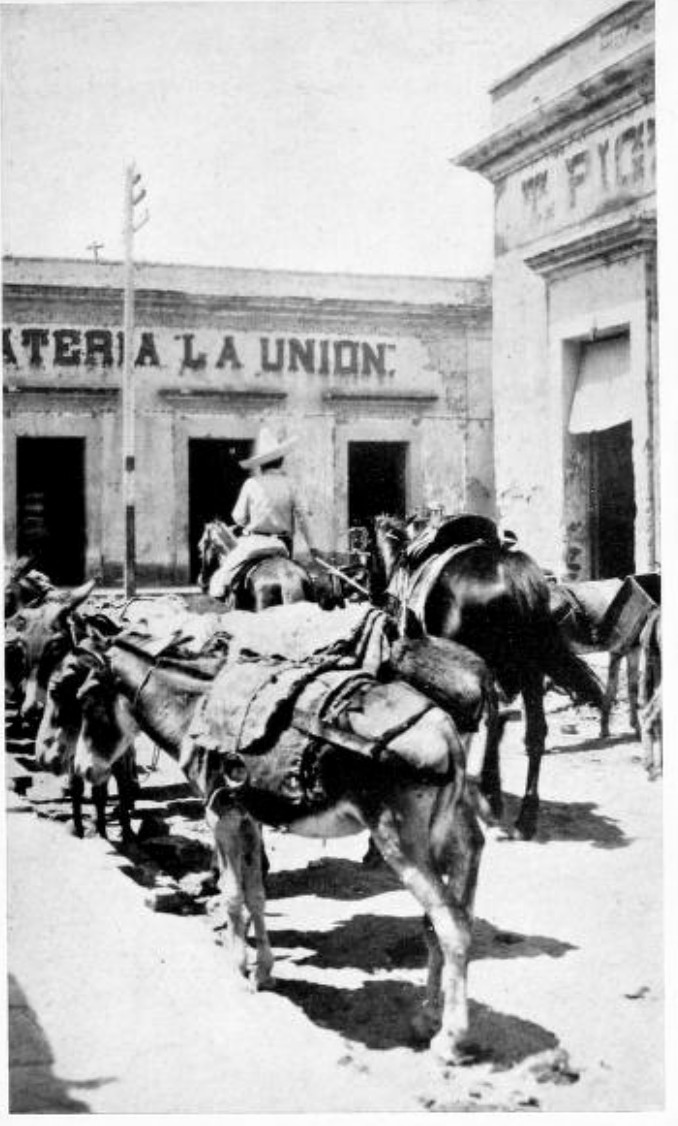

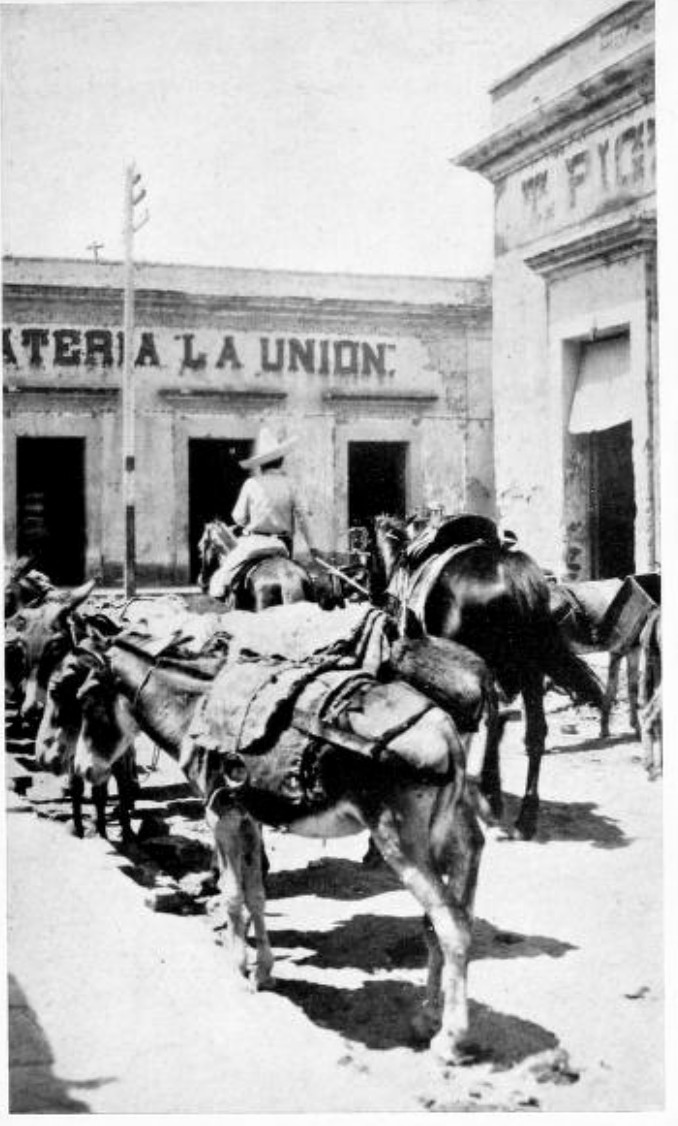

From the narrow street outside came the soft voices of peons, the sing-song call of a lottery-ticket vender, the tread of sandaled feet, the clatter of hoofs from a passing burro train laden with bullion from distant mines, the guttural protesting cry of the drivers, all in the exotic symphony of a foreign land.

A BURRO TRAIN LADEN WITH BULLION FROM THE MINES

Yet there was a calm, subdued note about the chorus. In Mexico, a newly arrived Gringo expected melodrama. It was disconcerting to find only peace.

An Indian maiden, straight as an arrow, swung past with the flat-footed stride of the shoeless classes, balancing an earthenware jar upon her dark head. A fat old lady cantered by upon a tiny donkey, perched precariously upon the extreme stern. A little brown runt of a man staggered past under a gigantic wooden table. Another staggered past under the influence of alcohol. Women on their way to market stopped to offer me their wares. Did I wish to buy a chicken or a watermelon? Would I care for a bouquet of yucca lilies? Or an umbrella? If not an umbrella, a second-hand guitar?

“No?” They seemed surprised and disappointed. But they smiled politely. “Gracias just the same, señor! Adios!”

An ice cream vender made his rounds with a slap of leather sandals, balancing atop his sombrero a dripping freezer. He stopped before a patron to dish the slushy mixture into a cracked glass, pushing it off the spoon with a dirty finger, and licking the spoon clean before he dropped it back into the can. From one pocket he produced bottles and poured coloring matter over the concoction—scarlet, green, and purple. Then he swung his burden aloft, and continued on his way, chanting, “I carry snow! I carry snow!”

Even the cries of a peddler were soft and gentle here. I was about to turn from the window, when around the corner came a strange procession of mournful men and wailing women, led by three coffins balanced, like every other species of baggage in this country, upon the heads of peons. Mexico was Mexico after all! Here was evidence of melodrama! Excitedly I hailed the proprietor.

“A bandit attack, señor? No, indeed. José Santos Dominguez had a christening at his house last night. Purely a family affair, señor! Nothing more.”

II

After the dusty railway journey I craved a bath.

From a doorway across the patio a legend beckoned with the inscription of “Baños.” I called an Indian servant-maid, pointed at the legend, struggled with Spanish, and finally secured a towel. The bath-room door, like that of my room, had long ago lost its lock. Searching among the several tin cans which littered one corner, I found a stick which evidently was used for propping against the door by such bathers as desired privacy. Having undressed, I leaped jubilantly into the huge, old-fashioned tub, and turned on the water. There was no water. Poking modest head and shoulders around the edge of the door, I looked for the maid. She eventually made her appearance, as servants will, even in Mexico, and regarded me suspiciously from a safe distance.

“No, señor, there is no water. You asked for a towel. You did not mention that you wished also a bath.”

“Well, for the love of Mike, when—”

“Mañana, señor. Always in the morning there is water.”

And so, after supper and a stroll in the plaza, I retired, still coated with Sonora desert, to my room. There was some difficulty in locating the electric button, since another careless mozo had backed the bureau against it. There was also some difficulty in arranging the mosquito net over my bed. It hung from the ceiling by a slender cord which immediately broke in the pulley. I piled a chair on top of a cot, climbed up and mended the string, climbed down and lowered the net to the proper height, unfolded it, and discovered that it was full of gaping holes through which not only a mosquito but possibly a small ostrich could have flown with comfort and security. Finally, beginning to feel that the charm of Mexico had been vastly overrated by previous writers, I retired, prepared to fight mosquitos, and discovered that there were no mosquitos in Hermosillo.

In the morning, rejuvenated and reënergized, I again waylaid the Indian servant-maid.

“Ah!” she exclaimed, as though it were a new idea. “The señor wishes a bath? Why not? Momentito! Momentito!”

“Momentito” is Spanish for “Keep your shirt on!” or “Don’t raise hell about it!” or more literally “In the tiny fraction of a moment!” It suggests to the native mind a lightning-like speed, even more than does “Mañana.”

And eventually I did get the bath. There was some delay while the water was heated, and more delay while the maid carried it, a kettleful at a time, from the kitchen to the bath-room, but the last kettle was ready by the time the rest had cooled, and I finally emerged refreshed, to discover again that in Mexico the unexpected always happens.

When I pulled out the old sock used as a stopper, the water ran out upon the bath-room floor, and disappeared down a gutter, carrying with it the shoes I had left beside the tub.

III

But Hermosillo possessed a charm which even a Mexican bath could not destroy.

It was a sleepy little city, typically Mexican, basking beneath a warm blue sky. It stood in a fertile oasis of the desert, and all about it were groves of orange trees. Its massive-walled buildings had once been painted a violent red or green or yellow, but time and weather had softened the barbaric colors until now they suggested the tints of some old Italian masterpiece. And although ancient bullet holes scarred its dwellings, there hung over the Moorish streets to-day a restful atmosphere of tranquillity.

At noon the merchants closed their shops, and every one indulged in the national siesta. The only exception was an American—a quiet, determined-looking man—who kept walking up and down the hotel patio with quick, nervous tread.

“Somebody just down from the States?” I asked the proprietor.

“No, señor. He is the manager of mines in the Yaqui country. One of his trucks is missing, and he fears lest Indians have attacked it.”

Such a contingency, in sleepy Hermosillo, sounded quite absurd. It was the most peaceful-appearing town in all the world. As the siesta hour drew to a close, the señoritas commenced to show themselves, dressed and powdered for their evening stroll in the plaza. They were dainty, feminine creatures, not always pretty, yet invariably with a gentle womanliness that gave them charm. Upon the streets they passed a man with modestly downcast head. Behind the bars of a window and emboldened by a sense of security, they favored him with a roguish smile from the depths of languorous dark eyes, and sometimes with a softly murmured, “Adios!”

I drifted toward the plaza, wondering how a Free-Lance Newspaper Correspondent were to earn a living in any country so outwardly unexciting as Mexico, and dropped disgustedly into a bench beside another young American.

He was a rosy-cheeked, cherubic-appearing lad. He wore horn-rimmed spectacles, and his neatly-plastered hair was parted in the middle. Like myself, he was dressed in a newly purchased palm-beach suit. His name was Eustace. He, too, was just out of the army. He had enlisted, he explained, in the hope that he might live down a reputation as a model youth. And the War Department had given him a tame job on the Mexican border, cleaning out the cages of the signal-corps pigeons. Wherefore he was now journeying into foreign fields in the hope of satisfying himself with some mild form of adventure.

Very solemnly we shook hands.

“I couldn’t quite go back to cub-reporting,” he explained. “So I decided to become a free-lance newspaper correspondent.”

Even more solemnly we shook hands again. Since neither of us actually expected that any editor would publish what we sent him, we formed a partnership upon the spot. The Expedition had a new recruit. And together we mourned the disappointing peacefulness of Hermosillo.

Evening descended upon the plaza. A circle of lights appeared around the rickety little bandstand. An orchestra played. The señoritas strolled past us, arm in arm, while stately Dons and solemn Doñas maintained a watchful chaperonage from the benches. The night deepened. The cathedral clock struck ten. Dons, Doñas, and señoritas disappeared in the direction of home. The gendarmes alone remained. Each muffled his throat as a precaution against night air, and each set a lantern in the center of a street crossing. From all sides came the sound of iron bars sliding into place behind heavy doors. Hermosillo was going to bed.

As we, also, turned homeward, our footsteps rang loudly through the silent streets. A policeman unmuffled his throat and bade us “Good night.” Then he produced a tin whistle and blew a melancholy little toot, to inform the policeman on the next corner that he was still awake. From gendarme to gendarme the signal passed, the plaintive wail seeming to say, “All’s well.”

A beggar huddled in a doorway hid his cigarette beneath his ragged blanket at our approach, and held out his hand. A lone wayfarer, lingering upon the sidewalk before a window, turned to glance at us, and to bid us “Adios.” Through the bars a girl’s radiant face shone out of the darkness. Then the man’s voice trailed after us, singing very softly to the throbbing of a guitar. A moon peeped over the edge of the low flat roofs—a very aged and battered-looking moon, with a greenish tinge like that of the old silver bells in Hermosillo’s ancient cathedral—a moon which, like the city below it, suggested that it once had known troublous days, yet was now at perfect peace.

This was a delightful land, but to a pair of Free-Lance Newspaper Correspondents—

As we entered the wide-arched portals of the hotel, the telephone struck a jarring note. The American mining man, still pacing nervously up and down the patio, leaped to the receiver.

“Laughlin speaking! What news? Did they—? Shot them both? White and Garcia both? Get the troops out! I’ll be there in just—”

IV

In an instant Eustace and I were at his elbow.

Ours was the newspaperman’s unsentimental eagerness, which might have hailed the burning of an orphan asylum with its four hundred helpless inmates as splendid front-page copy. Here was murder! This was Mexico! Viva Mexico! Here was our first story!

“No time to talk!” snapped Laughlin. “I’ll send John Luy for you in the morning. He’ll take you to La Colorada, in the Yaqui country itself. You’ll get the dope there!”

And he vanished down the street. We stood at the hotel gate, a little startled, gazing out into the night. The moon smiled down over low, flat roofs, and a man’s voice drifted to us, singing very softly to the throbbing of a guitar, and the plaintive note of a gendarme’s whistle seemed to say, “All’s well.”