CHAPTER IV

AMONG THE YAQUI INDIANS

I

John Luy met us in an elderly Buick early the next morning.

He was a stocky man in khaki and corduroy, a man of fifty or sixty, with slightly gray hair, and the keen, friendly eyes of the Westerner. He was a trifle deaf from listening to so many revolutions, and questions had to be repeated.

“Heh? Oh, the holes in the wind-shield? They’re only bullet holes.”

He motioned us into the back seat, grasped the wheel, and drove us out through the suburbs of Hermosillo into the open desert. The road was nothing more than the track of cars which had crossed the plains before us. Sometimes it led through wide expanses of dull reddish sand; sometimes the cactus and mesquite grew in thorny forests up to the very edge of the narrow trail.

It was a country alive with all the creeping, crawling things that supply local color for magazine fiction. Swift brown lizards shot from our path, starting apparently at full speed, and zigzagging through the yucca like tiny streaks of lightning. Chipmunks and ground squirrels dived into their burrows at our approach. A rattler lifted its head, hissed a warning, and retired with leisurely dignity. Jack-rabbits popped up from nowhere in particular and scampered into the brush, laying their ears flat against the head, running a dozen steps and finally bouncing away in a series of long, frantic leaps. Chaparral cocks, locally known as road-runners, sped along the trail before us, keeping about fifty feet ahead of the car, wiggling their tails in mocking challenge, slackening their pace whenever we slackened ours, speeding whenever we speeded, and shooting away into the mesquite in a low, jumping flight as John stepped on the gas.

Now and then we passed a mound of rocks surmounted by a crude wooden cross, and once we saw the wreck of what had been another automobile.

“Heh?” asked John. “Oh! Graves. People shot by Yaqui Indians. Oh, yes, quite a few of them. Quite a few.”

He gave the wheel a twist, and we plunged down a steep slope into a deep, sandy river-bed. The car lumbered through it, sinking to the hubs. In the very center it came to an abrupt stop. John picked up a rifle.

“One of you lads take the gun and lay out in the brush. This is the kind of place where White got his.”

Eustace seized the weapon, and crawled into the cactus, while I worked savagely to dig the wheels from their two-foot layer of soft, beach-like sand. John, puffing complacently at his corn-cob pipe, tried the self-starter again and again without success, meanwhile giving me the details of White’s murder:

“It was an arroyo exactly like this one. Exactly like this one. He come around a bend in his truck, and hit the waterhole, and was plowing through it when a dozen Mausers blazed out’n the cactus. Three bullets hit him square in the head. Maybe Garcia, his mechanic, got it on the first volley, too. You couldn’t be sure—so the fellows said over the telephone. The Yaquis had cut him up and shoved sticks through him ’til his own mother couldn’t’ve recognized him. Dig the sand away from that other wheel, will you?”

II

I breathed more freely half an hour later, when we climbed the farther bank of the river-course, and rattled on again, through ever-thickening forests of cactus, to the low adobe city of La Colorada.

John showed us a nondescript mud dwelling that passed for a hotel, and we presently sallied therefrom, with paper and pencil, fully convinced that the pleasantest method of securing copy would be that of sitting on the village hitching post and listening to the experiences of some one else.

There were half a dozen other Americans in La Colorada. It had once been the home of gold mines from which heavily-guarded mule trains carried away a hundred and eight millions of dollars in bullion, but revolutionists had destroyed the machinery during the turbulent years that led up to the Carranza régime, and the town now served only as a depot for the big motor trucks which ran through hostile Yaqui country to mines farther in the interior. The half dozen Americans were the drivers of these trucks. The eldest of them was under thirty, but most of them had knocked about the far corners of the earth since childhood, and all of them surveyed with undisguised contempt the little thirty-two-caliber automatics we carried.

LA COLORADA, ONCE THE HOME OF GOLD MINES, NOW SERVED ONLY AS A DEPOT FOR TRUCKS THAT CROSSED THE DESERT

“If you was to shoot me with one of them things, and I was ever to find it out,” said Dugan, a lad of twenty, “I’d be downright peeved about it.”

Dugan stood over six feet in height. His jaw resembled the Rock of Gibraltar, and his hair suggested Vesuvius in eruption. His favorite literature, I suspected, was the biography of Jesse James. He carried a forty-four in a soft-leather holster cut wide to facilitate a quick draw. His great ambition was to “shoot up” a saloon, and since there was no bar-room in La Colorada, he had recently compromised upon the local drug-stores, and had blazed holes through the pharmacist’s castor-oil bottles.

All of these youths had encountered the Yaquis. One showed us a dozen bullet-dents in his truck, mementos of a brush with Indians on his last trip. Another had been captured, stripped of his clothing, and chased naked back to town. But of the latest incident—the murder of White and Garcia—they could give us little information. W. E. Laughlin was supposed to have an understanding with the Yaqui chiefs whereby his property and his employees were protected.

“He pays ’em so much a year to leave him alone. He’s never had any trouble before this. A year ago one of his drivers was shot—Al Farrel—but it wasn’t Yaquis. It was a gang of Mexican soldiers. They robbed the truck and blamed it on the Indians, and went scouting all over the country pretending to chase the guys that did it. Maybe the same thing has happened again.”

“That’s about it,” echoed another. “The Yaquis hold us up, but it’s the Greasers they’ve got it in for. We get off light—usually. They just rob us. When they catch a Mex, they rip his clothes off and chuck him into the cactus, or cut the soles off his feet and make him dance on the hot sand.”

But the others disagreed. It was merely border tradition that the Yaquis treated Americans better than Mexicans. There was the case of Otto, the draft-dodger, who came to La Colorada to avoid the war, only to be caught by the Indians and tortured to death. There was the story of One-Legged Joe, who went prospecting just outside of town, and of whom nothing was found except the wooden leg, charred with fire. And there was the tragedy of Pedro Lehr, who left his ranch near Hermosillo for a few hours, and returned to find his entire family slain, with the exception of a sixteen-year-old daughter whom the Yaquis had carried away with them.

Pleased at our eager interest, the truck-drivers warmed toward us. Only Dugan remained aloof, grinning a trifle contemptuously. Eustace turned to him:

“What can you tell us?”

“What do you want to know?”

“Well, for a starter, how do you feel when you ride through hostile Indian country on a truckload of dynamite?”

Dugan spat eloquently upon the ground. Then he pointed toward two loaded trucks that stood in the road before us.

“MacFarlane over there is going out to a mine to-morrow. If you want to know how it feels, go along with him. He’s carrying six hundred pounds of dynamite.”

III

Since he put it that way, we sought out MacFarlane.

He was a tall, lean-faced man—one of the quiet, self-possessed, determined-looking mine superintendents usually encountered in Mexico. He was about to make a week’s trip to El Progresso mine, sixty miles farther in the interior. He would be glad to take us along.

And at dawn the following day, we rode out of La Colorada in one of MacFarlane’s trucks. We sat upon a miscellaneous assortment of machinery, provisions, and blasting powder, with a crew of twenty hired gunmen, each of whom wore several hundred yards of cartridge belt draped around his waist and criss-crossed over his shoulders in the approved Mexican style.

The desert seemed a trifle more forbidding than the one we had crossed the day before. When we were in the open our gunmen laughed and chatted together; when we approached the forests of yucca and mesquite, I noticed that they grew silent and watchful. But no sound came from the vast expanse of wasteland except the peaceful song of the locusts.

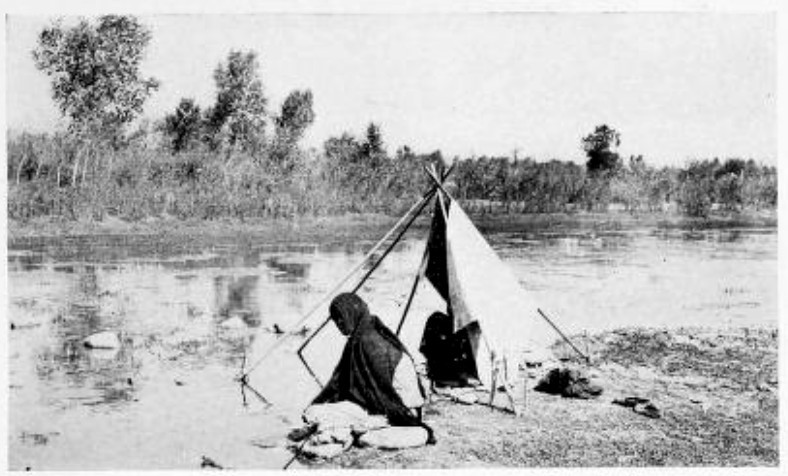

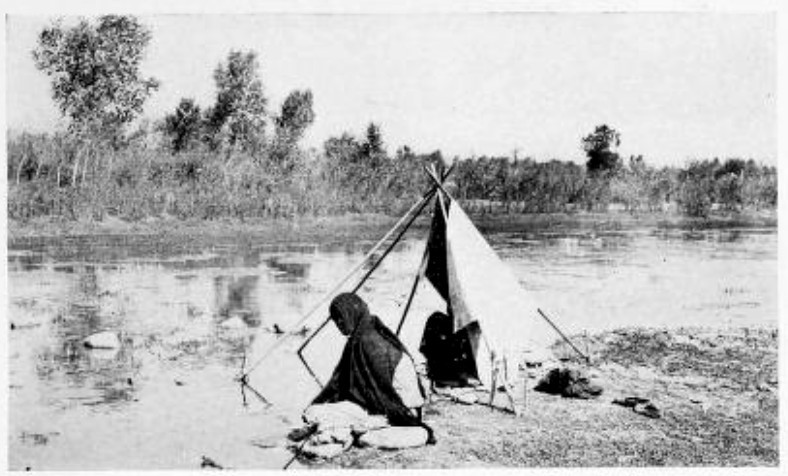

At rare intervals we passed a native village—a cluster of mud hovels surrounding an aged white church—and our advent created a sensation. A host of mongrel dogs but slightly removed from the coyote stage hailed us with furious yelps. Children raced barefoot beside the trucks to get a better view of us. Half-naked Indian women, pounding clothes upon the flat rocks beside a shallow brook, ceased their work to stare at us. Even the adult male population, reclining against the shady side of the adobe dwellings, sat up to look at us.

INDIAN WOMEN, POUNDING CLOTHES UPON THE ROCKS BESIDE A SHALLOW BROOK, CEASED THEIR WORK TO STARE

There was something in these tiny hamlets that recalled pictures of the Holy Land. Civilization had changed but little here since the days of the Aztecs, and despite the excitement caused by our passage, there was an air of sleepiness about the whole place which suggested another continent, a million miles farther from Broadway. So perfect was the scene that I resented the sight of a Standard Oil tin used as a water-jar, and felt distinctly offended when I heard the click of a Singer sewing machine issuing from a tiny, cactus-roofed hut.

The natives here showed little Spanish ancestry. Their features were purely Indian. A few, by their prominent cheek-bones and dark complexion, suggested a trace of Yaqui blood, but most of them were of other tribes, and all carried arms as a precaution against Yaqui raids. Every one wore a large knife, and in an open-air barber shop one native with a six-shooter on his belt was shaving another who held a rifle across his knees. All of them greeted us with the cry:

“Have you met any Yaquis?”

The day passed without incident, however, and nightfall brought us to our first stopping-place, the village of Matape, another cluster of mud hovels surrounding an ancient white church.

A buxom Indian woman, who operated a hotel on those rare occasions when visitors came to town, served us frijoles and tortillas—beans and cornmeal pancakes—and produced from its hiding place a bottle of fiery mescal. Later, when we had consumed the meal by the light of a flickering oil lamp, her daughter joined us with a guitar, and while MacFarlane watched his gunmen to see that no one kept the bottle too long inverted over his black moustachios, the girl sang to us. Still later, after she herself had sampled the potent Mexican liquor, she danced. She was rather comely, in a stolid Indian way, but she was much too heavy and graceless for complete success as a danseuse, even after two swigs of such inspiring stuff as mescal. The gunmen, however, found it highly diverting. They pushed back their chairs to clear a stage for her, and watched her with the pleased expression which a Mexican always wears when looking at a woman. The guitar twanged a weird, savage melody; the dim light from the swinging lantern shone upon a sea of dark faces, and reflected from a score of gleaming eyes; in the center of the crowded room the girl danced awkwardly, her bare feet pounding monotonously upon the mud floor.

As she finally sank, flushed and panting, upon a bench, her mother favored us with a toothless grin:

“For one hundred dollars gold I sell her!”

Eustace shook his head.

“She’s scarcely an essential part of a newspaper correspondent’s equipment.”

“Seventy-five!” persisted the woman.

“That’s a special rate,” exclaimed MacFarlane. “She lacks one ear. They say her last husband bit it off before chasing her home with a club. Of course, you can’t believe everything you hear. But you’d better turn in. To-morrow we travel on muleback.”

IV

The trucks were to continue, with the guard, by the longer road to the mine. MacFarlane and ourselves, with two of the gunmen, were to ride over the mountains. The bridle trail led through questionable territory, but it was shorter.

Neither Eustace nor I had ever ridden a mule before. Both of us had read Western fiction, and had noted that the hero not only loved his steed, but left nearly everything to the animal’s good judgment, and that the noble beast, appreciating and reciprocating his master’s affection and trust, invariably anticipated his every wish, and carried the hero out of every conceivable difficulty.

We had just discussed the matter, and had determined to encourage the same fond relationship with our prospective mounts, when MacFarlane rode up to the hotel with the five most woebegone-looking specimens of quadrupeds that we had ever seen.

“Cut a good big stick,” he advised.

Two minutes after mounting, I welcomed the suggestion. It seemed inhuman to beat anything so small as that mule, but the animal appeared not to mind it in the least. The moment I ceased whaling him, he assumed that this was where I wished to stop. His one virtue was that no matter how often he stumbled on the edge of a precipice, he never fell over.

“When you come to a tight place,” warned MacFarlane, “let the mule use his own judgment.”

And there were plenty of tight places. Hour after hour the path twisted through narrow ravines, along deep water-courses strewn with bowlders, down sandy embankments where the animals slid like toboggans, around narrow cliffs, and up sharp inclines where they fairly leaped from rock to rock. It was a gloriously desolate country, hideous perhaps, yet awesome in its ugly grandeur. Mountains reared themselves above the trail, covered sometimes with huge candelabra cactus, but usually bare and towering skyward like the battlements of a gigantic fortress. So fascinating was the whole panorama that four of us rode across a valley a full mile in length before we discovered that Eustace had disappeared.

MacFarlane stopped abruptly.

“Good Lord! I told him to keep close to us! Four months ago one of my men dropped behind, and they nabbed him so quietly we never heard a sound!”

He was off his mule in an instant, and leading the way on foot, revolver in hand, while I followed at his heels, both of us crouching behind bowlders as we hurried back along the path we had traversed. Turning a bend, we found Eustace sitting on his mule at the top of a sandy decline, complacently smoking a cigar.

“What the devil are you doing?” snapped MacFarlane.

“Tight place,” said Eustace. “I’m letting the mule use his own judgment.”

“Hell!” growled MacFarlane. “The mule’s gone to sleep!”

And throughout the day he lectured us upon the fallacies of the S.P.C.A. spirit as applied to Mexican mules, all the way to Suaqui de Batuc, another mud-village at the junction of the Yaqui and Moctezuma Rivers, where we were to spend another night.

There was no hotel in this town, but we found lodgings with an Indian family. A woman brought us the inevitable frijoles and tortillas, gave us water to drink which tasted as though it had been inhabited by frogs, and ushered us to one large bed which undoubtedly was inhabited by everything except frogs. The name of the town, I learned, when translated from the Indian, meant something which could be printed only in French. As I scratched myself to sleep, I reflected upon the appropriateness of the name. I had just succeeded in closing my eyes when a volley of pistol shots sounded outside the window. Eustace and I bumped heads in a frantic dive to locate the automatics beneath our pillow.

“Don’t worry,” said MacFarlane. “It’s a gang of drunks. This is a Saint’s Day, and the faithful are celebrating.”

V

In the morning, before continuing the journey, I set out to secure a few photographs.

“Ask permission before you snap a native,” the mining man warned me. “Some of them are superstitious—have an idea that they’ll die within a year if you take their picture. They killed the last photographer that tried it.”

So I took special pains to ask permission. Invariably they said, “No!” Some appeared to regard the camera as a new species of machine-gun. Even those who knew what it was were reticent about posing. The more picturesque the native, and the more I wished his picture, the more resolutely he said, “NO!”

Strolling some distance from town, I finally discovered an aged squaw who looked as though she might die within a year even though her photograph were not taken. But her “NO!” was not merely in capital letters but in type larger than the largest in a Hearst newspaper. Still, I could not resist that picture. She was standing in the center of the shallow river, filling deer-skin water-sacks and loading them upon the back of a moth-eaten little burro. But since the sun shone directly in my lens, I had to pass her. And the moment I unslung my camera, she started to walk upstream directly into the light. The faster I walked, the faster she walked. I broke into a trot, and she broke into a trot, dragging the burro after her, and splashing water over the two of us. I felt a trifle undignified, but I had determined to have that picture, and I increased my pace to a run. Thereupon she gathered her skirts about her waist and sprinted like an intercollegiate champion.

From the village behind us came a series of war-whoops. I looked back to see the entire population joining in the chase. Suddenly I realized that my behavior was undignified. Some fifty angry natives were rushing toward me, waving in the air an assortment of weapons that might have delighted a collector of antiques, but which at the moment gave me no cause whatsoever for rejoicing. I stopped and faced them, trying vainly to explain my conduct in my inadequate Spanish, while they shook their fists, and waved knives in the air, and jabbered furiously.

Eustace came to my rescue. Two years and eight sweethearts upon the border had given him a fluent command of the language.

“They’ve misjudged your intentions,” he chuckled, after he had calmed the mob. “I’ve explained it all. This old geezer with the four whiskers on his chin is her man, and he says he’ll let you take her picture for two pesos. I suppose he’s tired of her, and doesn’t care whether she croaks or not.”

But the squaw evidently valued her life at more than two pesos. For she gathered up her skirts once more, and fled away down the river, dragging the burro behind her.

VI

It was but a few hours’ ride from Suaqui to El Progresso Mine. It lay in the center of a ragged, bowl-shaped valley in the heart of the mountains, some ninety miles from the railroad—a group of gaping shafts beside a stone blockhouse, with a village of thatched laborers’ quarters straggling along a sandy, cactus-hedged street.

Some half dozen American bosses occupied the blockhouse. The native workmen numbered about two hundred, most of them Pimas and mestizos, or mixed-breeds.

“Don’t shoot at any rattlesnakes,” MacFarlane warned us, “or you’ll see everybody dropping work and running for headquarters to resist attack.”

The mine itself had never been threatened by the Yaquis, but on several occasions they had attempted to ambush the provision trucks. Like most of the mines in Mexico, El Progresso was not the sort where one had merely to walk out with a pick and chop large pieces of silver off a convenient mountain side; before a single speck of mineral could be extracted, it had been necessary to transport across the desert a hundred thousand dollars’ worth of machinery; every bit of it had been brought over the long trail on truck or muleback, and the journey of every train had meant the possibility of a fight with Indians.

The Yaquis of Sonora are closely related to the Apaches of our own border country. From the earliest coming of the white man, they have resented the invasion of their domain. The Spaniards were never able to conquer them. Porfirio Diaz, who pacified all the rest of Mexico, could never make the Yaquis recognize the sovereignty of the Mexican government over their territory. He sent expedition after expedition against them, depleted their ranks by constant warfare, and took thousands of prisoners whom he shipped to far-off Yucatan to labor as virtual slaves upon the henequin plantations. But the atrocities of the Diaz soldiers merely aggravated the Indians’ hatred of their would-be rulers.

From time to time, in more recent years, groups of Yaquis have made their peace with the Mexican authorities. Many of them, known as “manzos” in distinction from the “bravos” in the hills, are to be found in every Sonoran village and even in Arizona. As soldiers, they are the bravest in Mexico, and as laborers the most industrious. But they were never especially friendly to Carranza, and in his era, although some served in the federal army, they frequently did so in order to obtain arms or ammunition for their own use. Soldiers one day, they were apt to be bandits the next.

Although the Yaquis had first declared war upon the invading white man with every possible justification, they had been forced, through years of constant retreat into the unfertile recesses of the desert, to prey upon the invaders for a living. Although their original grievance had been against the Mexican, bandits can not be choosers. And the miners at El Progresso were always on the watch.

“It’s a bad time just now,” one man explained. “They all get together for a big hullabaloo every Easter, and drink a lot of mescal, and get so enthusiastic that they start out for a few more scalps.”

VII

I had witnessed the Easter ceremony of the Yaqui Indians before leaving the border.

Strange as it may sound, the Yaqui is a Christian. Years ago the Spanish missionaries, the greatest adventurers in all history, penetrated the Sonora desert where warriors feared to tread, and finding themselves unable to converse with the Indians, enacted their message in sign language. To-day, at Easter time, the Yaquis reënact the same story, distorted by their own barbaric conception of it until it is but a semi-savage burlesque upon the Passion Play.

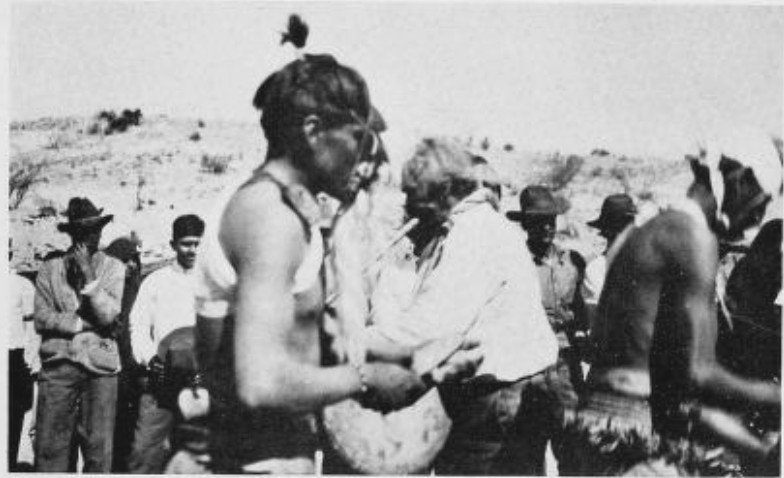

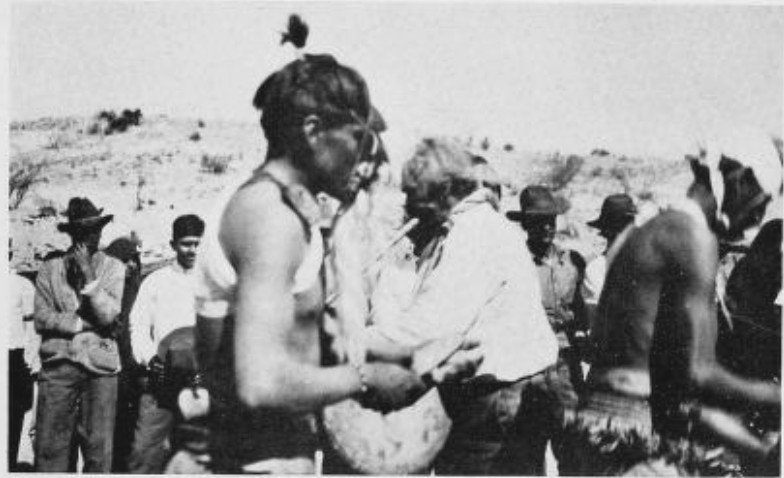

In the manzo settlement at Nogales, the Christ was represented by a cheap rag doll, garbed in brilliantly colored draperies, and cradled in a wicker basket beneath a thatched roof. The ceremonies lasted from Good Friday until after Easter Sunday, and during that time the Indians neither ate nor slept, refreshing themselves only with mescal.

The native conception of the life of Christ was that of a continual warfare with Judas. To make the odds harder for Him, they had six assistant Judases, selected—I was told—from the young braves who had committed the most sins during the current year.

THE CHRIST WAS REPRESENTED BY A CHEAP RAG DOLL CRADLED IN A WICKER BASKET

“We have several,” explained an intelligent old Indian, “because my people could not respect a Savior who allowed himself to be licked by any one man.”

The Judases appeared in startling devil masks, and for three days they capered before the Infant, contorting their semi-naked bodies, howling like fiends, poking Him with sticks, spitting upon Him, kissing Him in mockery, and challenging Him to come out and fight. About the cradle the women of the tribe sat cross-legged upon the ground, wailing a strange Indian hymn that rose and fell in plaintive minor key. A tomtom pounded monotonously. Night descended, and the fires threw weird, fantastic shadows upon the reddened mountain sides. Hour after hour, and day after day, the barbaric orgy continued, until on Easter Sunday the tribe rose in defense of the Christ, seized the Judases and carried them to the fire, where they pretended to burn them. Afterwards, they carried the image of the Savior in mournful procession to a little grave behind the village. It was a ridiculous travesty upon religion, yet one could not laugh. There was a solemnity in the faces of these people, as they followed the rag doll to its burial place. Many of the women were weeping. The men bared their heads, and there was true reverence in the dark, savage eyes. The capering of the devil-dancers had been ludicrous, yet now I found myself strangely impressed. And, anyhow, it is inadvisable to laugh at religious fanatics—especially if they happen to be Yaqui Indians.

FOR THREE DAYS THE INDIANS NEITHER ATE NOR SLEPT, REFRESHING THEMSELVES ONLY WITH MESCAL

VIII

The same ceremony is practiced, with variations in ritual, by the bravos in the hills.

Frequently, as the miner had suggested, it serves as a get-together for the Spring raiding season. Spring is harvest-time in southern Sonora, and an ideal time for the Yaquis to sweep down from the mountains and pillage the valleys which the Mexicans have taken from them. In the days of Carranza, the Indians not only invaded the rural districts, but carried their raids to the very outskirts of Guaymas and Hermosillo.

Word came to us at El Progresso that a band of the Indians was operating not far away. They had attacked several of the neighboring villages, and had visited the Gavilan Mine, another American concern in our district, where they had done the miners no bodily harm, but had left them without clothing or provisions.

“When we start back to-morrow, we’ll travel by night,” decided MacFarlane. “The Yaquis are superstitious about the crosses along the trail. The ghosts of the murdered men are supposed to be out for revenge after dark. That’s the safest time to travel.”

IX

We left at sunset, a little party of five.

As we rode silently toward the vague mountains ahead, their peaks became a magic crimson that deepened slowly to purple against a silver sky. We passed Suaqui, where the rivers gleamed like shining ribbons in the last faint twilight. Then the swift desert night was upon us, and we were riding into a deep pass, where the air grew strangely chill.

I can recall every minute of that long night. Perhaps the mule could see the path. I couldn’t. Now and then, as we ascended, I caught a momentary glimpse of the rider ahead, looming abnormally large against the sky. Usually I listened to the crunch of hoofs upon the gravel, and followed close behind. One had the sensation of being about to enter a tunnel into which the other riders had disappeared. When the faint moonlight seeped down into the pass, it converted each cactus into the semblance of a crouching Yaqui. And despite MacFarlane’s assertion that night travel was comparatively safe, neither he nor the others were taking chances. The howl of a coyote or the cooing of a dove brought every revolver out of its holster, for these noises, although common enough in the mountains, are sometimes used by the Indians as signals. Once, when something trailed us for half a mile through the brush, we all rode half-turned in the saddle, covering the spot where the twigs crackled. It was probably some animal—perhaps a mountain lion—following us out of curiosity, but we watched it, lest it prove a bandit.

Hour after hour we rode in silence through the black defiles. We knew whether we were ascending or descending only from the slant of the mule’s back. The nervous strain seemed to affect even the animals. When we paused at a mountain stream to water them, my own beast suddenly lashed at me with his heels, and bolted. I chased him several hundred yards up the ragged bed of the water-course, stumbling over slippery stones, and splashing into the pools until I finally captured him, both of us making enough noise—it seemed to me—to awaken any Yaqui within a mile.

And within a mile, we turned a bend, and found ourselves in the very center of an encampment! A score of camp-fires, dwindled to smoldering red ashes, lined the trail, and about them, as though they were the spokes of a wheel, a group of men were sleeping with feet toward the blaze, in Yaqui fashion, each man with a rifle beside him. Not a sentry had stopped us. Even as I realized where we were, I found that my mule was stepping over the recumbent figures.

One of the men awoke, yawned, and raised himself on an elbow to stare at us.

“Who are you?” demanded MacFarlane in Spanish.

“Federal soldiers,” and the man composed himself for another nap.

X

We rode into Matape at dawn, and a truck carried us back to La Colorada. Dugan offered his hand.

“I done you an injustice, pardners. I thought you’d be scared.”

Eustace and I, exchanging confidences in private, agreed that Dugan had done neither of us an injustice, but we kept this to ourselves.

John Luy, driving us back to Hermosillo in his Buick, seemed highly amused about the whole affair. He chuckled to himself for a long time before he spoke:

“It’s funny! Mack don’t usually make that ride at night. He did it to give you guys a thrill, and I suspect he got a thrill himself. Laughlin’s been investigat