Chapter 3 Dog gone Lymmer

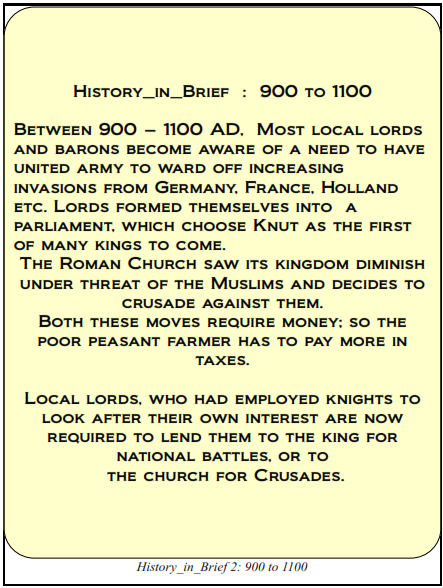

unting had taken place since Saxon times but the Norman Conquest gave it new vigour. During the time of relative peace, the knights and gentry needed to keep their fighting skills in tact. Barons would drive out whole villages of peasants in order to use forestry for their sport, they would justify the need saying ‘knights and fighting men needed to keep up training’. This might seem an extravagant excuse in the light of hunting today, but the savages of a wild bore, bull or cornered stag injured more knights than the crusades.

unting had taken place since Saxon times but the Norman Conquest gave it new vigour. During the time of relative peace, the knights and gentry needed to keep their fighting skills in tact. Barons would drive out whole villages of peasants in order to use forestry for their sport, they would justify the need saying ‘knights and fighting men needed to keep up training’. This might seem an extravagant excuse in the light of hunting today, but the savages of a wild bore, bull or cornered stag injured more knights than the crusades.

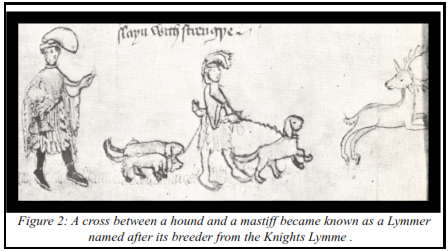

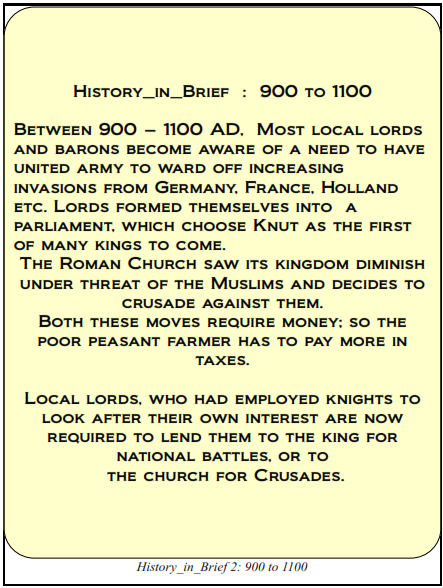

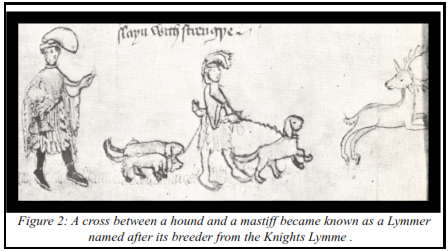

Indeed, many would-be-knights had to prove themselves in the woods before going on crusade.12 Every able bodied male was required to do archery practice daily during this period. Lymmer became common in the language around this time in two ways. First, kings and knights went hunting in their new laid forests. In Saxon times, hunting would be for rabbits or game birds, so the common hound was a useful dog to sniff out the catapulted food and bring it back to master. Hunting now became bigger and more ruthless. Poaching had to take care of the need for food whereas hunting for larger animals like stag, bull and wild bore, became the sport of the rich. The common hound was not ferocious enough to tackle bigger beasts so it was crossed with a mastiff to make it ferocious. This cross between a mastiff and a hound, known as a ‘ lymmer’ hound, is said to have taken its name from its breeder. Lymmes of Cheshire and Nottingham, besides being known for their ruthless manner, also attended the forest hunts with kings to chase wild pig and kings deer using these dogs. It is a small step to associate a derogatory remark about the ruthless behaviour of the knights with the dogs they led.

Some higher classes referred to this dog as a ‘ Lymer hound’ or ‘ Lymeshound’, perhaps the first denotes the vicious nature and the second the breeder's name. This new breed has the distinction of being the first dog to be leashed. Alluding to this animal’s qualities, in the poem ‘ The Hunting of Greene Lyon’, the writer draws a parallel with the ferocious killing nature of the dog that rendered the carcass useless and the nature of the recent trend in society to destroy the foundational philosophies of society.

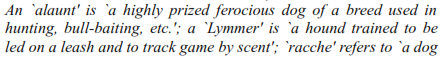

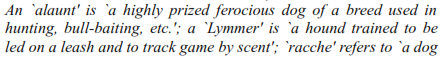

From the footnotes of ‘the Sultan of Babylon we can read:

that hunts by scent' (MED).

Again, according to Cummins,13 (C 1450), ‘… it was the job of the "lymerer” or “Limmer” (trainer/keeper of the Lymmer or hunting dog) or “local forester or parker" to direct the "master of game" to the best eligible hart as quarry …’.

Ferocious knights were said to ‘fight like a lymmer’. Today we simply say ‘fight like a dog’. Northumbrian thief’s were only called limmers if they used violence - for example a mugger. A little later, the rough cut shafts of a cart became known as limmers because of the way they were hacked roughly into shape with an axe.

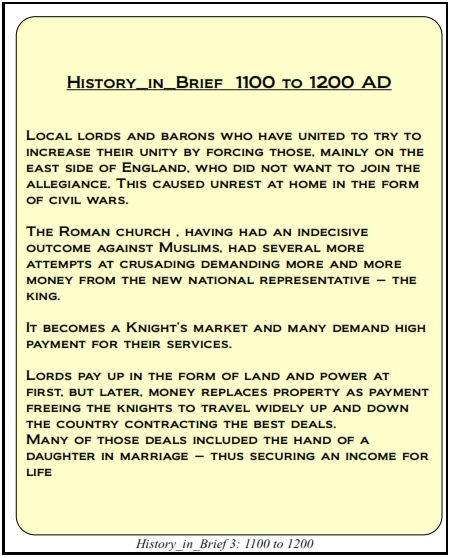

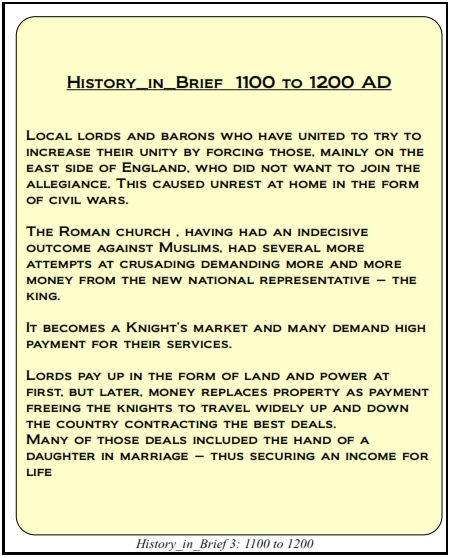

Second, Hunting was the sport of kings and barons who forbade commoners to organize or take part in such activities. The king’s orders to shire rulers to ‘… oust those peasant farmers and create a hunting forest’, cut across the conscience of many lords. Crossing the king meant losing ones position, (if not ones head). For many of these lords, position meant livelihood. There was little option but to ruthlessly drive villagers from their homelands; leaving them to roam. More sensitive lords and barons, (those with rather more ‘parliamentary’ leanings), began to take hold on the eastern side of the country where we find a more lenient approach to this problem. The church often helped here, although this might well have an opportunist motive. Around this time, especially in the south of England, bishops cleared church owned forests for new peasant villages-at a rent of course.

One change taking place at this time provided an escape for many Lords of conscience, money began to take the place of goods and lands as repayment of favour. Many on the west side of England, disconcerted by their lot, swapped their land for money or other lands on the west side where the king’s influence was greater. Knowing they would lose their land and power, some overlords negotiated to swap allegiance for land and power in another part of England.

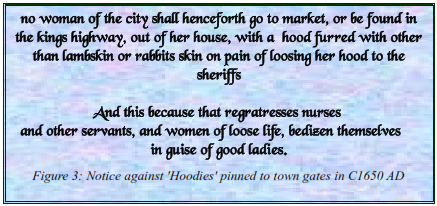

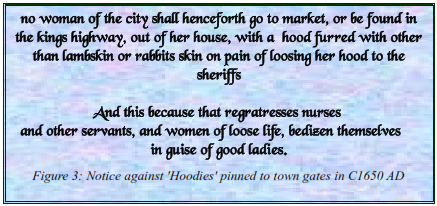

Lower classes, (plebs, commoners or peasants), having little money to carry with them also joined the migration. On arriving, many had to give way to lewd or loose behaviour in order to live. On arrival at the town gates many would be greeted by a notice warning of dress code. Such notices as the one in Figure 3 did little good because most commoners could not read.14 Quite why the term ‘limmer’ became synonymous with low or base fellows around this time is unclear. As we have discussed, it most likely due to the army attacks on northerners originated from Lyme, the term limmer became a derogatory term like ‘Pomes’- used of Australians against the British today.

Women were not excluded from the term, loose women were also known as limmers. According to Webster, Limmer came to mean:

‘a low base fellow or Prostitute’ as in : … Thieves,

Limmers and broken men of the Highlands.--

Sir W. Scott’15

Worse, in these times, when witches were drowned on ducking stools in a local pond, limmer became associated with this dubious profession.

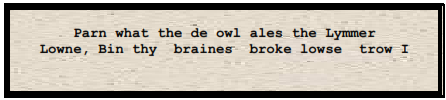

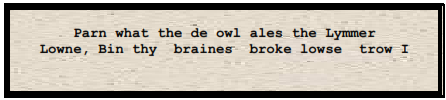

In the play ‘Lancaster witches16, we read these lyrics

unting had taken place since Saxon times but the Norman Conquest gave it new vigour. During the time of relative peace, the knights and gentry needed to keep their fighting skills in tact. Barons would drive out whole villages of peasants in order to use forestry for their sport, they would justify the need saying ‘knights and fighting men needed to keep up training’. This might seem an extravagant excuse in the light of hunting today, but the savages of a wild bore, bull or cornered stag injured more knights than the crusades.

unting had taken place since Saxon times but the Norman Conquest gave it new vigour. During the time of relative peace, the knights and gentry needed to keep their fighting skills in tact. Barons would drive out whole villages of peasants in order to use forestry for their sport, they would justify the need saying ‘knights and fighting men needed to keep up training’. This might seem an extravagant excuse in the light of hunting today, but the savages of a wild bore, bull or cornered stag injured more knights than the crusades.