Chapter 2 The Legacy of Lymme

he ravaging of land for profit and leaving it as wasteland seems to have expanded the term lymmer. Lymmes seem to have been quiet ruthlessness and profiteering; not only did they strip the land9 but in the courts they showed little mercy to their debtors. If defaulters could not pay, these knighted fellows would take the value by force.

he ravaging of land for profit and leaving it as wasteland seems to have expanded the term lymmer. Lymmes seem to have been quiet ruthlessness and profiteering; not only did they strip the land9 but in the courts they showed little mercy to their debtors. If defaulters could not pay, these knighted fellows would take the value by force.

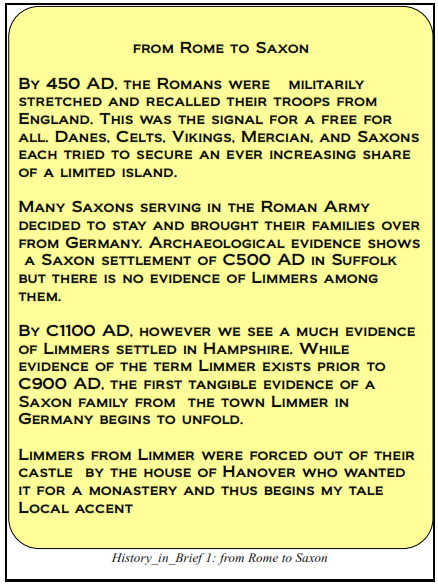

During the fifteenth century, the country itself divided in two ways. It divided between east and west England; those on the east were mainly loyalists while those on the west sought a parliament. England also divided between gentry and commoner. The rich ruling class would communicate in French and Latin while commoners continued with Saxon English. Many names of places and people changed as they passed between the lips of commoner and gentry. Lord of the manor, and many dignitaries became surnamed by notoriety only to be derided by the commoner who had his own version of the place. Question: What did knights do between crusades? Answer, look for ways to make more money at home. Actually, it is not at all clear that Gilbert de Lymme, who

became a fighting knight under Henry II, went to the crusades. Whether any Lymmes ever fought in the Crusades I do not know, but I rather think they hired themselves out to cover for fighting service at home.

It might better be supposed that Gilbert fought for the king in retaking Cumbria and Northumberland back from the Scottish King Malcolm IV. This campaign started from the district of Lymme in Cheshire. A number of people took part in the campaign and afterwards settled in the north of England. Commoners often used surnames of their rulers in derogatory ways as a way of handling their submission, so these were soon referred to as ' lymmers', not because they were descendants of Gilbert de Lymme but because they began the push for the north from Lymme. Northerners used the term lymmer in contempt of such coarse conquerors, not only because they took their land but also because they left it in a ruined state. While we are here, perhaps we can ask the question, Did the greater influence come from place Lymme or trade of lime-ing? The answer is; both seem to have reinforced it! The place and the trade grew together.

Situated near Lincoln, Great Limber, Limber Parva and Limber Magna were major sources of lime by the twelfth century. Wooden buildings gave way quickly to the new building techniques of brick and stone. The lime industry grew rapidly to keep up with demand. On the eastern side of the country, Chester and Limme produced companies to process lime for the building industry. Lime supplied by local yeomen was sold to people like John Limer who formed a company John Limer & Co.(C 1260) later known as Limer and Co. By 1265 their main office was near Bury St Edmunds, and branched as William Lymar of Cambridge. Adam Lymer formed another company in Cambridge around the same time.10 Those applying their trade to new stone buildings became known as lymers because the were cementing with Lyme. John, William and Adam all belong to one family, but early writers spelled their name several ways in one document. Thus, Limmer, Lymmer, Lymer and Lymar are assigned to the above, simply because they are all pronounced the same way.11 It would depend on the background of the scribe, was he, (and it was usually a male profession), used to writing the French way, the Latin way or the emerging English way. Generally those who took their name from the trade settled nicely to Limer or Limor, while those from the place or the tribe settled to Limmer. Quiet often the spelling would be written several different ways in one document. Sorting out which was which becomes a headache, but generally the context or some external evidence gives the game away.

he ravaging of land for profit and leaving it as wasteland seems to have expanded the term

he ravaging of land for profit and leaving it as wasteland seems to have expanded the term