CHAPTER XXVII.

RETURN TO THE SOUTHERN COAST—CAPTURE OF THE AMERICAN SLAVE-SHIP “MARTHA”—CLAIM TO BRAZILIAN NATIONALITY—LETTERS FOUND ON BOARD ILLUSTRATIVE OF THE SLAVE-TRADE—LOANDA—FRENCH, ENGLISH AND PORTUGUESE CRUISERS—CONGO RIVER—BOARDING FOREIGN MERCHANT VESSELS—CAPTURE OF THE “VOLUSIA” BY A BRITISH CRUISER—SHE CLAIMS AMERICAN NATIONALITY—THE MEETING OF THE COMMODORES AT LOANDA—DISCUSSIONS IN RELATION TO INTERFERENCE WITH VESSELS OSTENSIBLY AMERICAN—SEIZURE OF THE AMERICAN BRIGANTINE “CHATSWORTH”—CLAIMS BY THE MASTER OF THE “VOLUSIA.”

On the 6th of May, orders were given to the commander of the Perry, to proceed thence, with all practicable dispatch, to the southern coast; and to communicate with the commander of the John Adams as soon as possible. In case that vessel should have left the coast before the arrival of the Perry, her commander would proceed to cruise under former orders, and the instructions of the government.

It appeared to the commodore, in the correspondence had with some of the British officers, that in certain cases where they had boarded vessels under the flag of the United States, not having the right of search, threats had been used of detaining and sending them to the United States squadron. This he remarked was improper, and must not be admitted, or any understanding had with them authorizing such acts; adding, in substance, that if they chose to detain suspicious vessels, they must do it upon their own responsibility, without our assent or connivance. Refusing to the British government the right of search, our government has commanded us to prevent vessels and citizens of the United States from engaging in the slave-trade. These duties we must perform to the best of our ability, and we have no right to ask or receive the aid of a foreign power. “It is desirable to cultivate and preserve the good understanding which now exists between the two services; and should any differences arise, care must be taken that the discussions are temperate and respectful. You have full authority to act in concert with the British forces within the scope of our orders and duty.”

On the same day, the Perry again sailed for the south coast, and after boarding several vessels, which proved to be legal traders, a slaver was captured, and made the subject of a communication, dated June 7th, 1850.

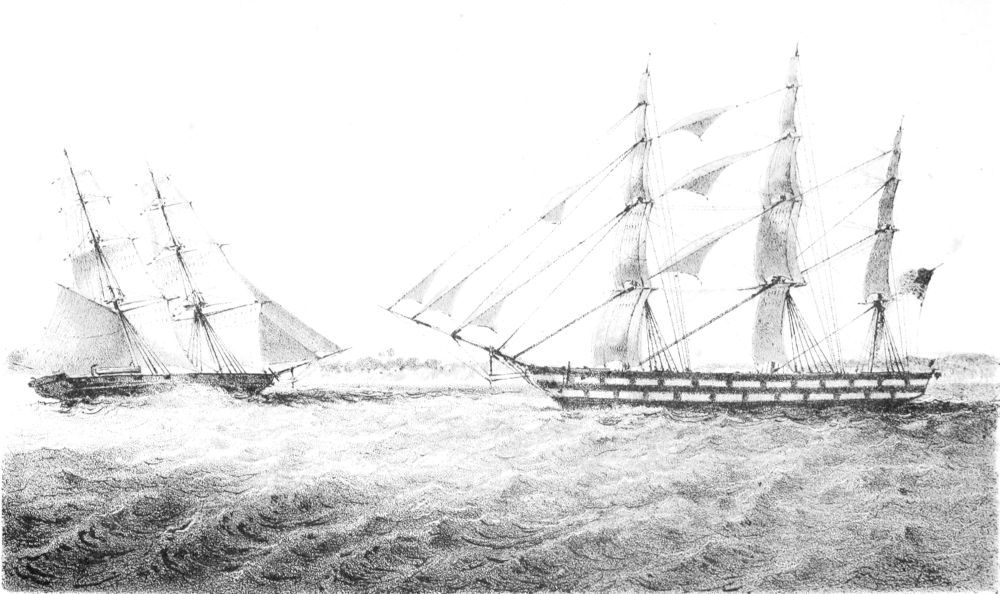

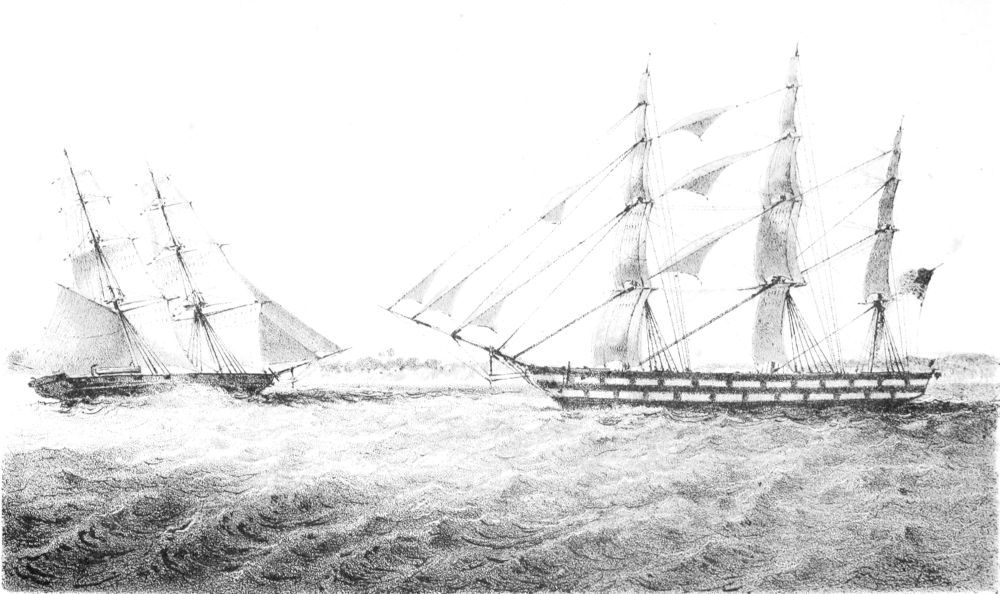

Lith. of Sarony & Co. N. Y

U. S. BRIG PERRY.

AMERICAN SLAVE SHIP MARTHA

“off Ambria June 6th 1850”—

In this it was stated to the commodore, that the Perry, agreeably to his orders, had made the best of her way for Ambriz, and arrived off that place on the 5th instant. It was there reported that the John Adams was probably at Loanda; and accordingly a course was shaped for that port. But on the 6th instant, at three o’clock in the afternoon, a large ship with two tiers of painted ports was made to windward, standing in for the land towards Ambriz. At four o’clock the chase was overhauled, having the name “Martha, New York,” registered on her stern. The Perry had no colors flying. The ship, when in range of the guns, hoisted the American ensign, shortened sail, and backed her main-topsail. The first lieutenant, Mr. Rush, was sent to board her. As he was rounding her stern, the people on board observed, by the uniform of the boarding-officer, that the vessel was an American cruiser. The ship then hauled down the American, and hoisted Brazilian colors. The officer went on board, and asked for papers and other proofs of nationality. The captain denied having papers, log, or any thing else. At this time something was thrown overboard, when another boat was sent from the Perry, and picked up the writing-desk of the captain, containing sundry papers and letters, identifying the captain as an American citizen; also indicating the owner of three-fifths of the vessel to be an American merchant, resident in Rio de Janeiro. After obtaining satisfactory proof that the ship Martha was a slaver, she was seized as a prize.

The captain at length admitted that the ship was fully equipped for the slave-trade. There were found on board the vessel, one hundred and seventy-six casks filled with water, containing from one hundred to one hundred and fifty gallons each; one hundred and fifty-barrels of farina for slave-food; several sacks of beans; slave-deck laid; four iron boilers for cooking slave-provisions; iron bars, with the necessary wood-work, for securing slaves to the deck; four hundred spoons for feeding them; between thirty and forty muskets, and a written agreement between the owner and captain, with the receipt of the owner for two thousand milreis.

There being thirty-five persons on board this prize, many of whom were foreigners, it was deemed necessary to send a force of twenty-five men, with the first and second lieutenants, that the prize might be safely conducted to New York, for which place she took her departure that evening.

Soon after the Martha was discovered, she passed within hailing distance of an American brig, several miles ahead of the Perry, and asked the name of the cruiser astern; on being told, the captain, in despair, threw his trumpet on deck. But on a moment’s reflection, as he afterwards stated, he concluded, notwithstanding, that she must be an English cruiser, not only from her appearance, but from the knowledge that the Perry had left for Porto Praya, and could not in the mean time have returned to that part of the coast. Therefore finding, when within gun-shot of the vessel, that he could not escape, and must show his colors, ran up the American ensign, intending under his nationality to avoid search and capture. The boarding-officer was received at the gangway by a Brazilian captain, who strongly insisted that the vessel was Brazilian property. But the officer, agreeably to an order received on leaving the Perry, to hold the ship to the nationality first indicated by her colors, proceeded in the search. In the mean time, the American captain, notwithstanding his guise as a sailor, being identified by another officer, was sent on board the Perry. He claimed that the vessel could not lawfully be subjected to search by an American man-of-war, while under Brazilian colors. But, on being informed that he would be seized as a pirate for sailing without papers, even were he not a slaver, he admitted that she was on a slaving voyage; adding, that, had he not fallen in with the Perry, he would, during the night, have shipped eighteen hundred slaves, and before daylight in the morning, been clear of the coast.

Possession was immediately taken of the Martha, her crew put in irons, and both American and Brazilian captains, together with three or four cabin passengers (probably slave-agents), were given to understand that they would be similarly served, in case of the slightest evidence of insubordination. The accounts of the prize crew were transferred, the vessel provisioned, and in twenty-four hours after her capture, the vessels exchanged three cheers, and the Martha bore away for New York.

She was condemned in the U. S. District Court. The captain was admitted to bail for the sum of five thousand dollars, which was afterwards reduced to three thousand: he then escaped justice by its forfeiture. The American mate was sentenced to the Penitentiary for the term of two years; and the foreigners, who had been sent to the United States on account of the moral effect, being regarded as beyond our jurisdiction, were discharged.

The writing-desk thrown overboard from the Martha, soon after she was boarded, contained sundry papers, making curious revelations of the agency of some American citizens engaged in the slave-trade. These papers implicated a number of persons, who are little suspected of ever having participated in such a diabolical traffic. A citizen of New York, then on the African coast, in a letter to the captain of the Martha, says: “The French barque will be here in a few days, and, as yet, the agent has no instructions as to her taking ebony [negroes, slaves].... From the Rio papers which I have seen, I infer that business is pretty brisk at that place.... It is thought here that the brig Susan would bring a good price, as she had water on board.... C., an American merchant, has sold the Flood, and she was put under Brazilian colors, and gone around the Cape. The name of the brigantine in which B. came passenger was the Sotind; she was, as we are told, formerly the United States brig Boxer.” Other letters found with this, stated: “The barque Ann Richardson, and brig Susan, were both sent home by a United States cruiser. The Independence cleared for Paraguay; several of the American vessels were cleared, and had sailed for Montevideo, &c., in ballast, and as I suppose bound niggerly; but where in hell they are is the big business of the matter. The sailors, as yet, have not been near me. I shall give myself no trouble about them. I have seen them at a distance. I am told that they are all well, but they look like death itself. V. Z. tells me they have wished a hundred times in his presence, that they had gone in the ship; for my part, I wish they were in hell, Texas, or some other nice place. B. only came down here to ‘take in,’ but was driven off by one of the English cruisers; he and his nigger crew were under deck, out of sight, when visited by the cruiser.”[8]

After parting company with the Martha, the Perry proceeded to Loanda, and found English, French and Portuguese men-of-war in port. The John Adams, having exhausted her provisions, had sailed for the north coast, after having had the good fortune to capture a slaver. The British commissioner called aboard, and offered his congratulations on the capture of the Martha, remarking that she was the largest slaver that had been on the coast for many years; and the effect of sending all hands found in her to the United States, would prove a severe blow to the iniquitous traffic. The British cruisers, after the capture of a vessel, were in the practice of landing the slave-crews, except when they are British subjects, at some point on the coast. This is believed to be required by the governments with which Great Britain has formed treaties.

At the expiration of a few days, the Perry proceeded on a cruise down the coast, towards the Congo River, encountering successively the British steamers Cyclops, Rattler, and Pluto. All vessels seen were boarded, and proved to be legal traders. Several days were spent between Ambriz and the Congo; and, learning from the Pluto—stationed off the mouth of the Congo River—that no vessels had, for a long time, appeared in that quarter, an idea, previously entertained, of proceeding up the river, was abandoned. The Perry was then worked up the coast towards Benguela.

Among the many incidents occurring:—On one occasion, at three o’clock in the morning, when the character of the vessels could not be discerned, a sail suddenly appeared, when, as usual on making a vessel at night, the battery was ordered to be cleared away, and the men sent to the guns. The stranger fired a musket, which was instantly returned. Subsequent explanations between the commanders of the cruisers were given, that the first fire was made without the knowledge of the character of the vessel; and the latter was made to repel the former, and to show the character of the vessel.

On boarding traders, the masters, in one or two instances, when sailing under a foreign flag, had requested the boarding-officer to search, and, after ascertaining her real character, to endorse the register. This elicited the following order to the boarding-officer:

“If a vessel hoists the American flag; is of American build; has her name and place of ownership in the United States registered on her stern; or if she has but part of these indications of American nationality, you will, on boarding, ask for her papers, which papers you will examine and retain, if she excites suspicion of being a slaver, until you have searched sufficiently to satisfy yourself of her real character. Should the vessel be American, and doubts exist of her real character, you will bring her to this vessel; or, if it can be done more expeditiously, you will dispatch one of your boats; communicating such information as will enable the commander to give specific directions, or in person to visit the suspected vessel.

“If the strange vessel be a foreigner, you will, on ascertaining the fact, leave her; declining, even at the request of the captain, to search the vessel, or to endorse her character,—as it must always be borne in mind, that our government does not permit the detention and search of American vessels by foreign cruisers; and, consequently, is scrupulous in observing towards the vessels of other nations, the same line of conduct which she exacts from foreign cruisers towards her own vessels.”

After cruising several days off the southern point designated in her orders, the Perry ran into Benguela. Spending a day in that place, she proceeded down the coast to the northward, occasionally falling in with British cruisers and legal traders. On meeting the Cyclops, the British commanding officer, in a letter, dated the 16th of July, stated to the commander of the Perry, that he “hastened to transmit, for his information, the following extract from a report just received from the commander of Her Britannic Majesty’s steam-sloop ‘Rattler,’ with copies of two other documents, transmitted by the same officer; and trusted that the same would be deemed satisfactory, as far as American interests were concerned.”

The extract gave the information, that on the 2nd of July, Her Majesty’s steam-sloop Rattler captured the Brazilian brigantine “Volusia,” of one hundred and ninety tons, a crew of seven men, and fully equipped for the slave-trade, with false papers, and sailing under the American flag; that the crew had been landed at Kabenda, and that the vessel had been sent to St. Helena for adjudication; and that he also inclosed certified declarations from the master, supercargo and chief mate, stating the vessel to be bona fide Brazilian property; that they had no protest to offer, and that themselves and crew landed at Kabenda of their own free will and consent.

On the following day, the commander of the Perry, in reply to the above communication, stated that, as the brigantine in question had first displayed American colors, he wished all information which could be furnished him in relation to the character of the papers found on board; the reason for supposing them to be false, and the disposition made of them. Also, if there was a person on board, apparently an American, representing himself, in the first instance, as the captain; and if the vessel was declared to be Brazilian on first being boarded, or not until after her capture had been decided upon, and announced to the parties in charge.

In reply to this letter, on the 23d of July, the commanding officer of the British division stated that he would make known its purport to the commander who had captured the Volusia, and call upon that officer to answer the questions contained in the communication of the 17th instant, and hoped to transmit his reply prior to the Perry’s departure for the north coast.

After cruising for several days in company with the English men-of-war, the vessel proceeded to Loanda, for the purpose of meeting the commodore. Arriving at that place, and leaving Ambriz without any guardianship for the morals of American traders, an order was transmitted to the acting first-lieutenant, to proceed with the launch on a cruise off Ambriz; and in boarding, searching, and in case of detaining suspected vessels, to be governed by the instructions therewith furnished him.

On the 5th of August, the British commissioner brought off intelligence that the American commodore was signalled off the harbor. The British commodore was at this date, also, to have rendezvoused at Loanda, that the subject-matter of correspondence between the officers of the two services, might be laid before their respective commanders-in-chief.

On the arrival of the American commodore, the Perry was reported, in a communication dated August the 5th, inclosing letters and papers, giving detailed information of occurrences since leaving Prince’s Island, under orders of the 6th of May; also sundry documents from the commander of the British southern division, in relation to the capture of the slave-equipped brigantine Volusia; adding, that this case being similar to a number already the subjects of correspondence, he had requested further information, which the British commander of the division would probably communicate in a few days.

The letter to the commodore also stated, that our commercial intercourse with the provincial government of Portugal, and the natives of the coast, had been uninterrupted. The question arising in regard to the treaty with Portugal, whether a vessel by touching and discharging part of the cargo at a native port, is still exempt from payment of one-third of the duties on the remaining portion of the cargo, as guaranteed by treaty, when coming direct from the United States, had been submitted to our government.

On the 15th of August the Cyclops arrived at Loanda, with the commander of the British southern division on board, who, in a letter dated the 12th of August, stated, that agreeably to the promise made on the 23rd ultimo, of furnishing the details from the commander who had captured the Volusia, he now furnished the particulars of that capture, which he trusted would prove satisfactory. He also gave information that the British commander-in-chief was then on the south coast, to whom all further reference must be made for additional information, in case it should be required. The reply from the officer who had captured the Volusia stated, that he had boarded her on the 2nd of July off the Congo River. She had the American ensign flying, and on the production of documents, purporting to be her papers, he at once discovered the register to be false: it was written on foolscap paper, with the original signature erased; her other papers were likewise forgeries. He therefore immediately detained her. They had been presented to him by the ostensible master, apparently an American, but calling himself a Brazilian, and claiming the protection of that empire. The register and muster-roll were destroyed by the master; the remainder of the records were sent in her to St. Helena, for adjudication. The British commander further stated, that on discovering the Volusia’s papers to be false, her master immediately hauled down the ensign, and called from below the remainder of the crew, twelve in number, all Brazilians.

In a letter dated the 15th of August, the above communications were acknowledged, and the British commander informed that the American commander-in-chief was also on the south coast: that all official documents must be submitted to him, and that the reply of the 12th instant, with its inclosure, had been forwarded accordingly.

The British commodore soon arrived at Loanda, and after an exchange of salutes, an interview of three hours between the two commodores took place. The captures of the Navarre, Volusia, and other vessels, with cases of interference with vessels claiming American nationality, were fully and freely discussed. The British commodore claimed that the vessels in question, were wholly, or in part Brazilian; adding, that had they been known clearly as American, no British officer would have presumed to capture, or interfere with them. The American commodore argued from documents and other testimony, that bonâ fide American vessels had been interfered with, and whether engaged in legal or illegal trade, they were in no sense amenable to British cruisers; the United States had made them responsible to the American government alone—subject to search and capture by American cruisers, on good grounds of suspicion and evidence of being engaged in the slave-trade; which trade the United States had declared to be piracy in a municipal sense—this offence not being piracy by the laws of nations: adding, in case of slavers, “we choose to punish our own rascals in our own way.” Several discussions, at which the commander of the Perry was present, subsequently took place, without any definite results, or at least while that vessel remained at Loanda. These discussions were afterwards continued. In the commodores, both nations were represented by men of ability, capable of appreciating, expressing and enforcing the views of their respective governments.

Every person interested in upholding the rights of humanity, or concerned in the progress of Africa, will sympathize with the capture and deliverance of a wretched cargo of African slaves from the grasp of a slaver, irrespective of his nationality. But it is contrary to national honor and national interests, that the right of capture should be entrusted to the hands of any foreign authority. In a commercial point of view, if this were granted, legal traders would be molested, and American commerce suffer materially from a power which keeps afloat a force of armed vessels, more than four times the number of the commissioned men-of-war of the United States. The deck of an American vessel under its flag, is the territory of the United States, and no other authority but that of the United States must ever be allowed to exercise jurisdiction over it. Hence is apparent the importance of a well-appointed United States squadron on the west coast of Africa.

On the 18th of August, the captain of an English cruiser entered the harbor with his boat, leaving the vessel outside, bringing the information that a suspected American trader was at Ambriz. The captain stated that he had boarded her, supposing she might be a Brazilian, but on ascertaining her nationality, had left her, and proceeded to Loanda, for the purpose of communicating what had transpired.

On receiving this information, the commodore ordered the Perry to proceed to Ambriz and search the vessel, and in case she was suspected of being engaged in the slave-trade, to bring her to Loanda. In the mean time a lieutenant who was about leaving the squadron as bearer of dispatches to the Government, volunteered his services to take the launch and proceed immediately to Ambriz, as the Perry had sails to bend, and make other preparations previous to leaving. The launch was dispatched, and in five hours afterwards the Perry sailed. Arriving on the following morning within twelve miles of Ambriz, the commander, accompanied by the purser and the surgeon, who volunteered their services, pulled for the suspected vessel, which proved to be the American brigantine “Chatsworth,” of Baltimore. The lieutenant, with his launch’s crew, was on board. He had secured the papers and commenced the search. After taking the dimensions of the vessel, which corresponded to those noted in the register, examining and comparing the cargo with the manifest, scrutinizing the crew list, consular certificate, port clearance, and other papers on board, possession was taken of the Chatsworth, and the boarding-officer directed to proceed with her, in company with the Perry, to Loanda.

Both vessels having arrived, a letter to the following purport was addressed to the commodore: “One hundred bags of farina, a large quantity of plank, sufficient to lay a slave-deck, casks and barrels of spirits, in sufficient quantity to contain water for a large slave-cargo, jerked beef, and other articles, were found on board the Chatsworth. These articles, and others on board, corresponded generally with the manifest, which paper was drawn up in the Portuguese language. A paper with the consular seal, authorizing the shipment of the crew, all foreigners, was also made out in the Portuguese language. In the register, the vessel was called a brig, instead of a brigantine. A letter of instructions from the reputed owner, a citizen of Baltimore, directed the American captain to leave the vessel whenever he should be directed to do so by the Italian supercargo. These, together with the report that the vessel on her last voyage had shipped a cargo of slaves, and her now being at the most notorious slave-station on the coast, impressed the commander of the Perry so strongly with the belief that the Chatsworth was a slaver, that he considered it his duty to direct the boarding-officer to take her in charge, and proceed in company with the Perry to Loanda, that the case might undergo a more critical examination by the commander-in-chief.”

The commodore, after visiting the Chatsworth in person, although morally certain she was a slaver, yet as the evidence which would be required in the United States Courts essential to her condemnation, was wanting, conceived it to be his duty to order the commander of the Perry to surrender the charge of that vessel, and return all the papers to her master, and withdraw his guard from her.

The captain of the Volusia now suddenly made his appearance at Loanda, having in his possession the sea-letter which the British commander who had captured him called a register, written on a sheet of foolscap paper, which from misapprehension he erroneously stated was destroyed by the master. This new matter was introduced in the discussion between the two commodores. The captain of the Volusia claimed that his vessel was bonâ fide American, stating that the sea-letter in his possession was conclusive evidence to that effect. No other subject than that of the nationality of the vessel, while treating upon this matter with an English officer, could be introduced. The sea-letter was laid before the commanders. This document bore all the marks of a genuine paper, except in having the word “signed” occurring before the consul’s signature, and partially erased. This seemed to indicate that it had been made out as a copy, and, if genuine, the consul had afterwards signed it as an original paper. The consular seal was impressed, and several other documents, duly sealed and properly certified, were attached, bearing strong evidence that the document was genuine.

The British commodore argued that the erasure of the word “signed,” even if it did not invalidate the document, gave good ground for the suspicion that the document was a forgery; and she being engaged in the slave-trade, the officer who captured her regarded the claim first set forth to American nationality as groundless.

The American commodore could not permit the character of the vessel to be assigned as a reason for her capture, and confined the discussion to the papers constituting the nationality of the vessel. He regarded the consular seal as genuine, and believed that, if the paper had been a forgery, care would have been taken to have had it drawn up without any erasure, or the word “signed.”

The discussion in relation to the Volusia and the Navarre, was renewed with the Chief-Justice and Judge of the Admiralty Court, soon after the arrival of the Perry at the island of St. Helena.

“FOREIGN OFFICE, November 18, 1850.

“SIR,—I herewith transmit to you, for your information, a copy of a dispatch from the commodore in command of H. M. squadron on the west coast of Africa, respecting the circumstances under which the ship Martha was captured, on the 6th of June (1850) last, fully equipped for the slave-trade, by the U. S. brig-of-war Perry, and sent to the United States for trial.

“I have to instruct you to furnish me with a full report of the proceedings which may take place in this case before the courts of law in the United States.

“PALMERSTON.”