CHAPTER XXVIII.

ANOTHER CRUISE—CHATSWORTH AGAIN—VISIT TO THE QUEEN NEAR AMBRIZETTE—SEIZURE OF THE AMERICAN BRIGANTINE “LOUISA BEATON” BY A BRITISH CRUISER—CORRESPONDENCE—PROPOSAL OF REMUNERATION FROM THE CAPTORS—SEIZURE OF THE CHATSWORTH AS A SLAVER—ITALIAN SUPERCARGO—MASTER OF THE LOUISA BEATON.

The commodore, on the 24th of August, intimated that it had been his intention to relieve the Perry from the incessant duties which had been imposed upon her, but regretted that he could not then accomplish it without leaving American interests in that quarter unprotected, and that the commander would therefore be pleased to prepare for further service on the southern coast, with the assurance of being relieved as soon as practicable.

Orders were issued by the commodore to resume cruising upon the southern coast, as before, and to visit such localities as might best insure the successful accomplishment of the purposes in view.

Authority was given to extend the cruise as far as the island of St. Helena, and to remain there a sufficient length of time to refresh the crew; and, after cruising until the twentieth of November, then to proceed to Porto Praya, touching at Monrovia, if it was thought proper.

The orders being largely discretionary, and the Chatsworth still in port, and suspected of the intention of shipping a cargo of slaves at Ambriz, the Perry sailed, the day on which her orders were received, without giving any intimation as to her cruising-ground. When outside of the harbor, the vessel was hauled on a wind to the southward, as if bound up the coast, and continued beating until out of sight of the vessels in the harbor. She was then kept away to the northward, making a course for Ambriz, in anticipation of the Chatsworth’s soon sailing for that place.

The cruising with the English men-of-war was resumed. A few days after leaving Loanda, when trying the sailing qualities of the vessel with a British cruiser, a sail was reported, standing down the land towards Ambriz. Chase was immediately made, and, on coming within gun-shot, a gun was fired to bring the vessel to. She hoisted American colors, but continued on her course. Another gun, throwing a thirty-two pound shot across her bows, brought the Chatsworth to. She was then boarded, and again searched, without finding any additional proof against the vessel’s character.

After remaining a day or two off Ambriz, the Perry proceeded to Ambrizette, a short distance to the northward, leaving one of the ship’s boats in charge of an officer, with orders to remain sufficiently near the Chatsworth, and, in case she received water-casks on board, or any article required to equip a slave-vessel, to detain her until the return of the Perry.

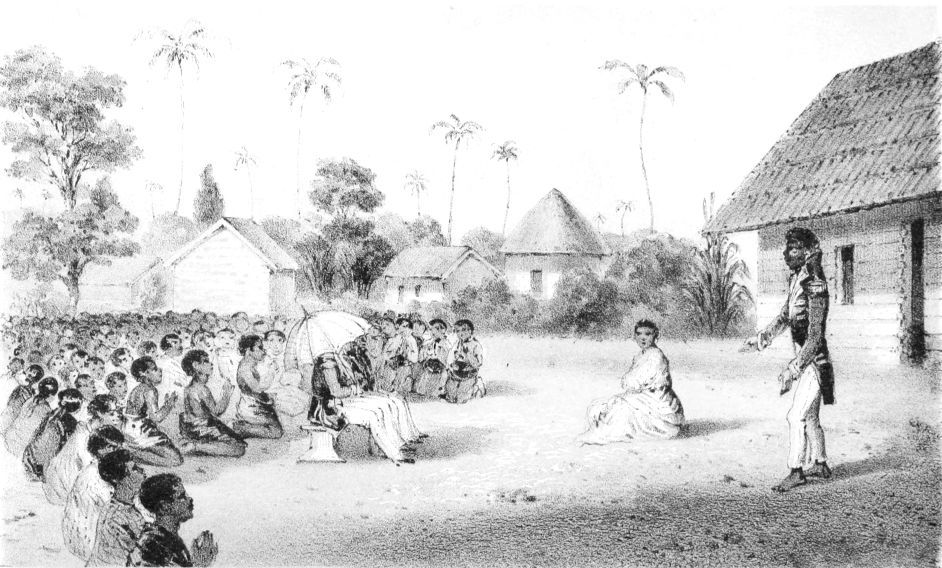

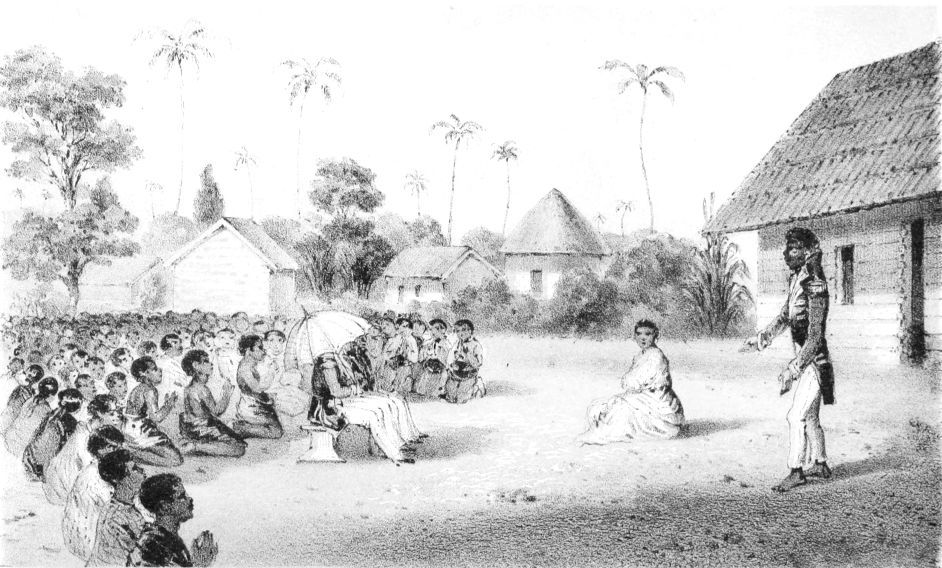

When the vessel had reached her destination, the commander conceived it to be a good opportunity to forward the interests of American commerce, by paying a visit of conciliation to the queen of that region. Though warned by the British officers that the natives were hostile to all persons engaged in suppressing the lucrative trade in slaves, he resolved to avail himself of the invitation of the resident American factor, and proceed to the royal residence. Two other officers of the vessel, the agent, and several of the gig’s Kroomen, accompanied him. On their way, a great number of Her Majesty’s loyal subjects—dressed chiefly in the costume of their own black skins—formed the escort. “All hands,” however, were not in the native sables exclusively, for several, of more aristocratic claims, sported a piece of calico print, of glaring colors, over one shoulder. The village, when first seen, resembled a group of brown haystacks; the largest of these, as a palace, sheltered the royal presence. The court etiquette brought the mob of gentlemen and ladies of the escort, with and without costume, down upon their knees, in expectation of Her Majesty’s appearance. A little withered old woman then stepped out, having, in addition to the native costume, an old red silk cloak, drawn tight around her throat, and so worn as to make her look like a loose umbrella, with two handles. She then squatted on the ground. Her prime minister aspired to be higher than African in his costume, by hanging on his long, thin person, an old full-dress French navy uniform-coat, dispensing with other material articles of clothing, except a short pair of white trowsers. The officers being seated in front, the kneeling hedge of three or four hundred black woolly heads closed behind them,—impregnating the air with their own peculiar aroma—their greasy faces upturned in humble reverence—hands joined, palm to palm, ready to applaud Her Majesty’s gracious wisdom when they heard it,—the conference began. The interpreter introduced the officers, and their business, and, in the name of the commander, expressed their friendly feelings towards Her Majesty and her people; advising her to encourage trade with the American merchants in gums, copper and the products of the country, instead of selling her people as slaves, or conniving at the sale in other tribes, for the purpose of procuring goods. This speech having the honor of being directed to the royal ears, was greeted, according to etiquette, with clap, clap, clap, from all the ready hands of all the gentlemen in waiting, who were using their knees as supports in Her Majesty’s royal presence. The prime minister, from the inside of the French coat, then responded—that Her Majesty had great reason to complain of the conduct of cruisers’ boats on the coast, for they were in the habit of chasing the fishermen, and firing to bring them to, and taking their fish, which were the principal support of the people, without making an equivalent return. Whereupon, clap, clap, clap, went the hands again. Her Majesty was assured, in reply, that such had never been, and never would be the case, in regard to the boats of American cruisers, and that her complaints would be made known to those officers who had the power and the disposition to remove all such cause of grievance. The chorus of clap, clap, clap, again at this answer concluded the ceremony. The prime minister followed the return escort at some distance, and took occasion, at parting on the beach, to intimate that there were certain other marks of friendly respect common at courts, and marking the usages of polished nations. He gave no hints about gold snuff-boxes, as might be suitable in the barbarian courts of Europe; but intimated that his friends visiting Her Majesty, in such instances, thought his humble services worthy of two bottles of rum. Compliance with this amiable custom was declared to be wholly impracticable, as the spirit-room casks of the Perry had been filled only with pure (or impure) water, instead of whisky, during the cruise.

Lith. of Sarony & Co. N. Y.

AUDIENCE TO THE PERRY’S OFFICERS, BY THE QUEEN OF AMBRIZETTE.

In communicating to the government, in a more official form, the object and incidents of the visit to the queen near Ambrizette, reference was made to a powerful king, residing ten miles in the interior of Ambriz, and the intention of making him a visit was announced. But the seizure of the Louisa Beaton by a British cruiser, on her return to the coast, and the impression made upon the natives by the capture of the Chatsworth as a slaver, not only occupied the intervening time before leaving for St. Helena, but rendered inland excursions by no means desirable.

On returning towards Ambriz, soon after making the land, the steamer Cyclops, with another British cruiser, was observed; and also the Chatsworth, with an American brigantine lying near her. A boat from the Cyclops, with an English officer, pulled out several miles, while the Perry was in the offing, bringing a packet of letters and papers marked as usual, “On Her Britannic Majesty’s Service.” These papers were accompanied by a private note from the British commander of the division, expressing great regret at the occurrence, which was officially noticed in the accompanying papers, and the earnest desire to repair the wrong.

The official papers were dated September the ninth, and contained statements relating to the chasing, boarding and detention of the American brigantine Louisa Beaton, on the seventh and eighth instant.

The particulars of the seizure of the vessel were given in a letter from the commander of the English cruiser Dolphin, directed to the British commander of the division, as follows: “I have the honor to inform you, that at daylight on the 7th instant, being about seventy miles off the land, a sail was observed on the lee bow, whilst Her Majesty’s brigantine, under my command, was steering to the eastward. I made all possible sail in chase: the chase was observed making more sail and keeping away. Owing to light winds, I was unable to overtake her before 0h. 30m. A. M. When close to her and no sail shortened, I directed a signal gun to be fired abeam, and hailed the chase to shorten sail and heave to. Chase asserted he could not, and requested leave to pass to leeward; saying, if we wanted to board him, we had better make haste about it, and that ‘we might fire and be damned.’

“I directed another gun to be fired across her bows, when she immediately shortened sail and hove to: it being night, no colors were observed flying on board the chase, nor was I aware of her character.

“I was proceeding myself to board her, when she bore up again, with the apparent intention of escaping. I was therefore again compelled to hoist the boat up and to close her under sail. I reached the chase on the second attempt, and found her to be the American brigantine Louisa Beaton. The master produced an American register, with a transfer of masters: this gave rise to a doubt of the authenticity of the paper, and on requesting further information, the master refused to give me any, and declined showing me his port clearance, crew list, or log-book.

“The lieutenant who accompanied me identified the mate as having been in charge of the slave-brig Lucy Ann, captured by Her Majesty’s steam-sloop Rattler. Under these suspicious circumstances, I considered it my duty, as the Louisa Beaton was bound to Ambriz, to place an officer and crew on board of her, so as to confer with an American officer, or yourself, before allowing her, if a legal trader, to proceed on her voyage.”

The British commander of the division, in his letter, stated, that immediately on the arrival of the vessels, he proceeded with the commander of the Dolphin and the lieutenant of the Rattler to the brigantine Louisa Beaton. Her master then presented the register, and also the transfer of masters made in Rio, in consequence of the death of the former master, but refused to show any other documents.

On examining the register, and having met the vessel before on that coast, he decided that the Louisa Beaton’s nationality was perfect; but that the conduct pursued by her master, in withholding documents that should have been produced on boarding, had led to the unfortunate detention of the vessel.

The British commander further stated, that he informed the master of the Louisa Beaton that he would immediately order his vessel to be released, and that on falling in with the commander of the Perry, all due inquiry into the matter for his satisfaction should be made; but that the master positively refused to take charge again, stating that he would immediately abandon the vessel on the Dolphin’s crew quitting her; and, further, requested that the vessel might be brought before the American commander.

That, as much valuable property might be sacrificed should the master carry his threat into execution, he proceeded in search of the Perry, that the case might be brought under consideration while the Dolphin was present; and on arriving at Ambriz, the cutter of the Perry was found in charge of one of her officers.

On the following morning, as he stated, accompanied by the officer in charge of the Perry’s cutter, and the commander of the Dolphin, he proceeded to the Louisa Beaton, and informed her master that the detention of his vessel arose from the refusal, on his part, to show the proper documents to the boarding-officer, authorizing him to navigate the vessel in those seas; and from his mate having been identified by one of the Dolphin’s officers, as having been captured in charge of a vessel having on board five hundred and forty-seven slaves, which attempted to evade search and capture by displaying the American ensign; as well as from his own suspicious maneuvering in the chase. But as he was persuaded that the Louisa Beaton was an American vessel, and her papers good, although a most important document was wanting, namely, the sea-letter, usually given by consular officers to legal traders after the transfer of masters, he should direct the commander of the Dolphin to resign the charge of the Louisa Beaton, which was accordingly done; and, that on meeting the commander of the Perry, he would lay the case before him; and was ready, if he demanded it, to give any remuneration or satisfaction, on the part of the commander of the Dolphin, for the unfortunate detention of the Louisa Beaton, whether engaged in legal or illegal trade, that the master might in fairness demand, and the commander of the Perry approve.

After expressing great regret at the occurrence, the British commander stated that he was requested by the captain of the Dolphin to assure the commander of the Perry, that no disrespect was intended to the flag of the United States, or even interference, on his part, with traders of America, be they legal or illegal; but the stubbornness of the master, and the identifying of one of his mates as having been captured in a Brazilian vessel, trying to evade detection by the display of the American flag, had led to the mistake.

A postscript to the letter added, “I beg to state that the hatches of the Louisa Beaton have not been opened, nor the vessel or crew in any way examined.”

On the Perry’s reaching the anchorage, the Louisa Beaton was examined. The affidavit of the master, which differs not materially from the statements of the British officers, was taken. A letter by the commander of the Perry was then addressed to the British officer, stating, that he had in person visited the Louisa Beaton, conferred with her master, taken his affidavit, examined her papers, and found her to be in all respects a legal American trader. That the sea-letter which had been referred to, as being usually given by consular officers, was only required when the vessel changes owners, and not, as in the present case, on the appointment of a new master. The paper given by the consul authorizing the appointment of the present master, was, with the remainder of the vessel’s papers, strictly in form.

The commander also stated that he respectfully declined being a party concerned in any arrangement of a pecuniary nature, as satisfaction to the master of the Louisa Beaton, for the detention and seizure of his vessel, and if such arrangement was made between the British officers and the master of the Louisa Beaton, it would be his duty to give the information to his government.

The commander added, that the government of the United States did not acknowledge a right in any other nation to visit and detain the vessels of American citizens engaged in commerce: that whenever a foreign cruiser should venture to board a vessel under the flag of the United States, she would do it upon her own responsibility for all consequences: that if the vessel so boarded should prove to be American, the injured party would be left to such redress, either in the tribunals of England, or by an appeal to his own country, as the nature of the case might require.

He also stated that he had carefully considered all the points in the several communications which the commander of the British division had sent him, in relation to the seizure of the Louisa Beaton, and he must unqualifiedly pronounce the seizure and detention of that vessel wholly unauthorized by the circumstances, and contrary both to the letter and the spirit of the eighth article of the treaty of Washington; and that it became his duty to make a full report of the case, accompanied with the communications which the British commander had forwarded, together with the affidavit of the master of the Louisa Beaton, to the government of the United States.

This letter closed the correspondence.[9]

The British commander-in-chief then accompanied the commander of the Perry to the Louisa Beaton, and there wholly disavowed the act of the commander of the Dolphin, stating, in the name of that officer, that he begged pardon of the master, and that he would do any thing in his power to repair the wrong; adding, “I could say no more, if I had knocked you down.”

The Louisa Beaton was then delivered over to the charge of her own master, and the officer of the cutter took his station alongside of the Chatsworth.

On the 11th of September this brigantine was seized as a slaver. During the correspondence with the British officers in relation to the Louisa Beaton, an order was given to the officer of the cutter, to prevent the Chatsworth from landing the remaining part of her cargo. The master immediately called on board the Perry, with the complaint, that his vessel had been seized on a former occasion, and afterwards released by the commodore, with the endorsement of her nationality on the log-book. Since then she had been repeatedly searched, and now was prevented from disposing of her cargo; he wished, therefore, that a definite decision might be made. A decision was made by the instant seizure of the vessel.

Information from the master of the Louisa Beaton, that the owner of the Chatsworth had in Rio acknowledged to him that the vessel had shipped a cargo of slaves on her last voyage, and was then proceeding to the coast for a similar purpose—superadded to her suspicious movements, and the importance of breaking up this line of ostensible traders, but real slavers, running between the coasts of Brazil and Africa—were the reasons leading to this decision.

On announcing the decision to the master of the Chatsworth, a prize crew was immediately sent on board and took charge of the vessel. The master and supercargo then drew up a protest, challenging the act as illegal, and claiming the sum of fifteen thousand dollars for damages. The supercargo, on presenting this protest, remarked that the United States Court would certainly release the vessel; and the proçuro of the owner, with other parties interested, would then look to the captor for the amount of damages awarded. The commander replied, that he fully appreciated the pecuniary responsibility attached to this proceeding.

The master of the Louisa Beaton, soon after the supercargo of the Chatsworth had presented the protest, went on shore for the purpose of having an interview with him, and not coming off at the time specified, apprehensions were entertained that the slave-factors had revenged themselves for his additional information—leading to the seizure of the Chatsworth. At nine o’clock in the evening, three boats were manned and armed, containing thirty officers and men,—leaving the Perry in charge of one of the lieutenants. When two of the boats had left the vessel, and the third was in readiness to follow, the master of the Louisa Beaton made his appearance, stating that his reception on shore had been any thing but pacific. Had the apprehensions entertained proved correct, it was the intention to have landed and taken possession of the town; and then to have marched out to the barracoons, liberated the slaves, and made, at least for the time being, “free soil” of that section of country.

In a letter to the commodore, dated September 14th, information was given to the following purport:

“Inclosed are affidavits, with other papers and letters, in relation to the seizure of the American brigantine Chatsworth. This has been an exceedingly complicated case, as relating to a slaver with two sets of papers, passing alternately under different nationalities, eluding detection from papers being in form, and trading with an assorted cargo.

“The Chatsworth has been twice boarded and searched by the commander, and on leaving for a short cruise off Ambrizette, a boat was dispatched with orders to watch her movements during the absence of the Perry. On returning from Ambrizette, additional evidence of her being a slaver was procured. Since then the affidavits of the master of the Chatsworth and the mate of the Louisa Beaton have been obtained, leading to further developments, until the guilt of the vessel, as will be seen by the accompanying papers, is placed beyond all question.”

The Italian supercargo, having landed most of the cargo, and his business being in a state requiring his presence, was permitted to go on shore, with the assurance that he would return when a signal was made. He afterwards came within hail of the Chatsworth, and finding that such strong proofs against the vessel were obtained, he declined going on board, acknowledging to the master of the Louisa Beaton that he had brought over Brazilian papers.

The crew of the Chatsworth being foreigners, and not wishing to be sent to the United States, were landed at Ambriz, where it was reported that the barracoons contained four thousand slaves, ready for shipment; and where, it was said, the capture of the Chatsworth, as far as the American flag was concerned, would give a severe and an unexpected blow to the slave-trade.

After several unsuccessful attempts to induce the supercargo of the Chatsworth to come off to that vessel, a note in French was received from him, stating that he was “an Italian, and as such could not be owner of the American brig Chatsworth, which had been seized, it was true, but unjustly, and against the laws of all civilized nations. That the owner of the said brig would know how to defend his property, and in case the judgment should not prove favorable, the one who had been the cause of it would always bear the remorse of having ruined his countryman.”

After making the necessary preliminary arrangements, the master, with a midshipman and ten men, was placed in charge of the Chatsworth; and on the 14th of September, the following order was sent to the commanding officer of the prize: “You will proceed to Baltimore, and there report yourself to the commander of the naval station, and to the Secretary of the Navy. You will be prepared, on your arrival, to deliver up the vessel to the United States marshal, the papers to the judge of the United States District Court, and be ready to act in the case of the Chatsworth as your orders and circumstances may require.

“It is advisable that you should stand as far to the westward, at least, as the longitude of St. Helena, and when in the calm latitudes make a direct north course, shaping the course for your destined port in a higher latitude, where the winds are more reliable.”

On the following morning the three vessels stood out to sea—the Perry and Louisa Beaton bound to Loanda, and the Chatsworth bearing away for the United States. The crew had now become much reduced in numbers, and of the two lieutenants, master, and four passed midshipmen, originally ordered to the vessel, there remained but two passed midshipmen, acting lieutenants on board.

After a protracted trial, the Chatsworth was at length condemned as a slaver, in the U. S. District Court of Maryland.