CHAPTER XXIX.

PROHIBITION OF VISITS TO VESSELS AT LOANDA—CORRESPONDENCE—RESTRICTIONS REMOVED—ST. HELENA—APPEARANCE OF THE ISLAND—RECEPTION—CORRESPONDENCE WITH THE CHIEF-JUSTICE—DEPARTURE.

Soon after arriving at Loanda, it was ascertained that the masters of merchant-traders were forbidden to visit one another on board their respective vessels, without express permission from the authorities. This regulation was even extended to men-of-war officers in their visit to merchant vessels of their own nation. An application was made to the authorities, remonstrating against this regulation being applied to the United States officers; and assurances were given which led to the conclusion that the regulation had been rescinded.

Soon afterwards a letter to the collector, dated the 17th of September, stated that the commander of the Perry, in company with the purser, had that evening pulled alongside of the Louisa Beaton, and much to his surprise, especially after the assurance of the collector that no objection would in future be raised against the United States naval officers visiting the merchant vessels of their own nation, the custom-house officers informed him that he could not be admitted on board: they went on board, however, but did not go below, not wishing to involve the vessel in difficulty.

The report of this circumstance was accompanied with the remark, that it was the first time that an objection had been raised to the commander’s visiting a merchant vessel belonging to his own nation in a foreign port; and this had been done after the assurance had been given, that in future no obstacles should be in the way of American officers visiting American ships in Loanda.

In reply to this letter, the collector stated that he had shown, on a former occasion, that his department could give no right to officers of men-of-war to visit merchant vessels of their own nation when in port, under the protection of the Portuguese flag and nation. But in view of the friendly relations existing between Portugal and the United States, and being impressed with the belief that these visits would be made in a social, friendly character, rather than with indifference and disrespect to the authorities of that province, he would forward, and virtually had forwarded already, the orders, that in all cases, when American men-of-war are at anchor, no obstacle should be thrown in the way of their officers boarding American vessels.

He further stated, that the objections of the guards to the commander boarding the Louisa Beaton, was the result of their ignorance of his orders, permitting visits from American vessels of war; but concluded that the opposition encountered could not have been great, as the commander himself had confessed that he had really boarded the said vessel.

On the 19th of September, the Perry sailed for the island of St. Helena. Soon after leaving port, a vessel was seen dead to windward, hull and courses down. After a somewhat exciting chase of forty-two hours, the stranger was overhauled, and proved to be a Portuguese regular trader between the Brazil and the African coast.

Several days before reaching St. Helena, the trades had so greatly freshened, together with thick, squally weather, that double-reefed topsails, with single-reefed courses, were all the sail the vessel could bear.

On the morning of the 11th of October, a glimpse of the island was caught for a few minutes. Two misty spires of rock seemed to rise up in the horizon—notched off from a ridge extended between them—the centre being Diana’s peak, twenty-seven hundred feet in height. The vessel was soon again enveloped in thick squalls of rain, but the bearings of the island had been secured, and a course made for the point to be doubled. After running the estimated distance to the land, the fog again lifted, presenting the formidable island of St. Helena close aboard, and in a moment all was obscured again. But the point had been doubled, and soon afterwards the Perry was anchored, unseeing and unseen.

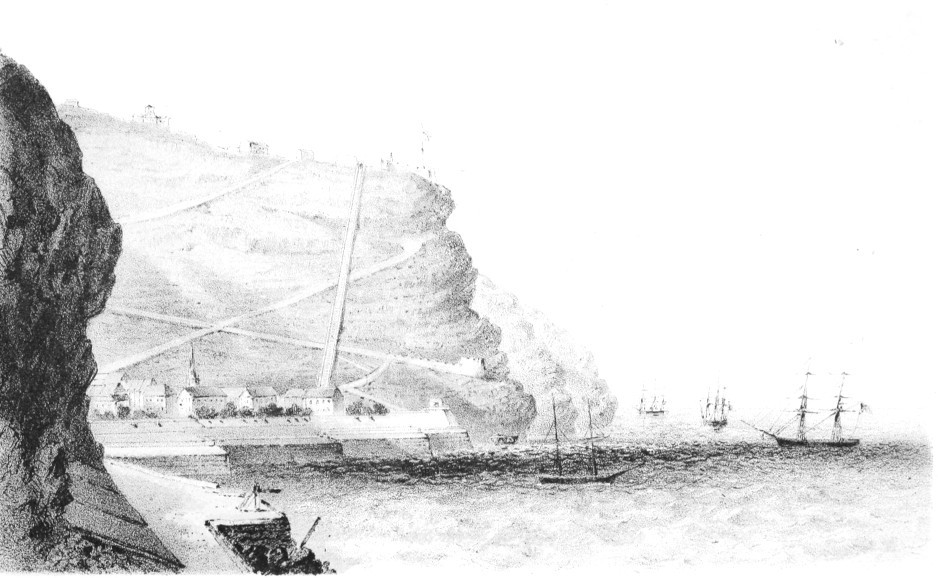

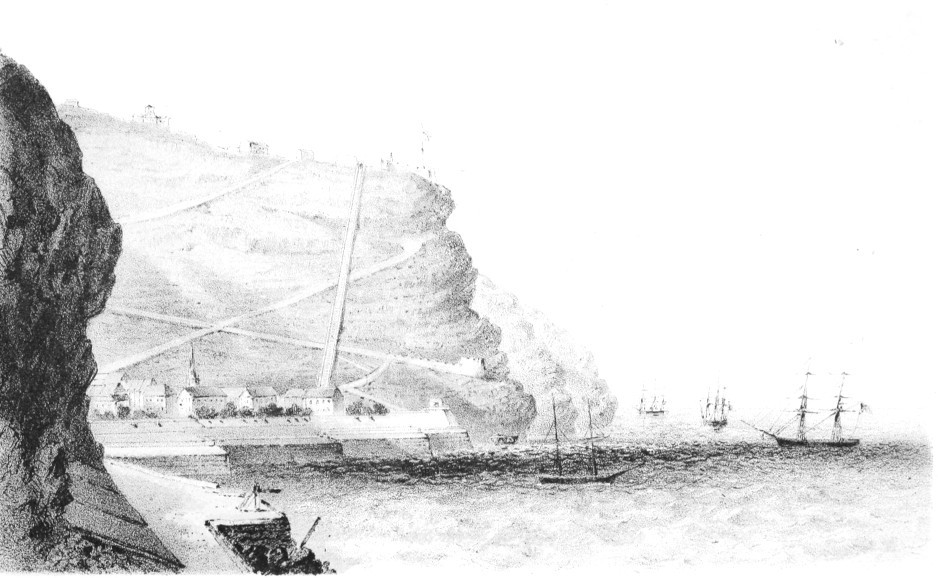

Lith. of Sarony & Co. N. Y.

SHORE AND ROADSTEAD AT JAMESTOWN, St. HELENA.

The sails were furled, the decks cleared up, when the whole scene started out of obscurity. St. Helena was in full view. A salute of twenty-one guns was fired, and promptly responded to, gun for gun, from the bristling batteries above.

Under the vast, rugged buttresses of rock—serrated with gaps between them, like the surviving parapets of a gigantic fortress, the mass of which had sunk beneath the sea—the vessel seemed shrunk to a mere speck; and close under these mural precipices, rising to the height of two thousand feet, she had, in worse than darkness, crept along within hearing of the surf.

On either bow, when anchored, were the two stupendous, square-faced bluffs, between which, liked a ruined embrasure, yawned the ravine containing Jamestown. High and distant against the sky, was frowning a battery of heavy guns, looking down upon the decks; and beyond the valley, the road zigzagged along the nine hundred feet of steep-faced, ladder hill. Green thickets were creeping up the valleys; and plains of verdant turf here and there overlapped the precipices.

Subsequently, on an inland excursion, were seen the fantastic forms of Lot and his wife, more than fourteen hundred feet in height; and black pillars, or shafts of basaltic columns, standing high amid the snowy foam of the surf. Patches of luxuriant vegetation were suddenly broken by astounding chasms, such as the “Devil’s Punch Bowl.”

This striking and majestic scenery, on an island ten miles in length and six in breadth, arises from its great height and its volcanic configuration. The occurrence of small oceanic deposits high up on its plains, indicates fits of elevation ere it reached its present altitude. The Yam-flowers (the sobriquet of the island ladies) need not, however, fear that the joke of travellers will prove a reality, by the island again being drawn under water like a turtle’s head.

Visits were received from the chief-justice, the commandant and officers of the garrison. Invitations were sent to dine “with the mess.” The American consul, and many of the inhabitants, joined in extending unbounded hospitality to the officers, which was duly appreciated by African cruisers. A collation to their hospitable friends, on the quarterdeck of the Perry, was also partaken of by the officers of a British cruiser, which, on leaving the island, ran across the stern of the vessel, gave three cheers, and dipped her colors. The proprietor of Longwood, once the prison of Napoleon, received the officers and their friends at a pic-nic, when a visit was made to that secluded spot, so suggestive of interesting associations. Every means was used to leave a sense of grateful remembrance on the minds of the visitors to the island.

One watch of the crew were constantly on shore, in search of health and enjoyment.

A short time previously to leaving Loanda, information being received from the American consul at Rio, that the barque Navarre, and brigantine Volusia, already noticed, had been furnished with sea-letters as American vessels, steps were taken to ascertain from the vice-admiralty court, in St. Helena, the circumstances attending their trial and condemnation. Calls were made on several officers of the court for that purpose. Failing thus to obtain the information unofficially, a letter was drawn up and sent to the chief-justice, who was also the judge of the admiralty court. After the judge had read the letter, he held, with the commander of the Perry, a conversation of more than an hour, in reference to its contents. During this interview, the judge announced that he could not communicate, officially, the information solicited. An opportunity, however, was offered to look over the record of the proceedings. Circumstances did not seem to justify the acceptance of this proposal. It was then intimated to the commander that the letter of request would be sent to Lord Palmerston; and, in return, intimation was also given that a copy of the letter would be transmitted to the Secretary of the Navy at Washington.

The social intercourse between the parties, during this interview, was of the most agreeable character.

In the same letter to the judge of the admiralty court, that contained the above-mentioned request for documents relating to the case of the Navarre, the commander of the Perry stated that he was informed by the American consul that the Navarre was sold in Rio to a citizen of the United States; that a sea-letter was granted by the consul; that the papers were regular and true; that the owner was master, and that the American crew were shipped in the consul’s office.

The commander also stated, that information from other sources had been received, that the Navarre proceeded to the coast of Africa, and when near Benguela was boarded by H. B. Majesty’s brig Water-Witch, and after a close examination of her papers was permitted to pass. The captain of the Navarre, after having intimated his intention to the officer of the Water-Witch, of going into Benguela, declined doing so on learning that the Perry was there, assigning to his crew as the reason, that the Perry would take him prisoner; and at night accordingly bore up and ran down towards Ambriz. The captain also stated to a part of the crew, that the officer of the Water-Witch had advised him to give up the vessel to him, as the Perry would certainly take his vessel, and send him home, whereas he would only take his vessel, and let him land and go free.

On reaching Ambriz, with the American flag flying, the Navarre was boarded by the commander of H. M. steam-sloop Fire-Fly, who, on examining the papers given by the consul, and passed by the commander of the Water-Witch as being in form, pronounced them false. The captain of the Navarre was threatened with being taken to the American squadron, or to New York; and fearing worse consequences in case he should fall into the hands of the American cruisers, preferred giving up his vessel, bonâ fide American, to a British officer. Under these circumstances, he signed a paper that the vessel was Brazilian property, and he himself a Brazilian subject. The mate was ordered to haul down the American and hoist the Brazilian colors; in doing which the American crew attempted to stop him, when the English armed sailors interfered, and struck one of the American crew on the head.

The Fire-Fly arrived at Loanda a few days after the capture of the Navarre, and the representations of her commander induced the commander of the Perry to believe that the Navarre was Brazilian property, and captured with false American papers; which papers having been destroyed, no evidence of her nationality remained but the statement of the commander of the Fire-Fly. This statement, being made by a British officer, was deemed sufficient, until subsequent information led to the conclusion, that the Navarre was an American vessel, and whether engaged in legal or illegal trade, the course pursued towards her by the commanders of the Water-Witch and the Fire-Fly, was wholly unauthorized; and her subsequent capture by the commander of the Fire-Fly, was in direct violation of the treaty of Washington.

After this statement was drawn up, the Water-Witch being in St. Helena, it was shown to her commander.

A statement in relation to the capture and condemnation of the Volusia, was also forwarded to the chief-justice: stating, upon the authority of the American consul at Rio, that she had a sea-letter, and was strictly an American vessel, bought by an American citizen in Rio de Janeiro.

In reply to this application for a copy of the proceedings of the Admiralty Court in relation to the Navarre, the chief-justice, in a letter to the commander of the Perry, stated that he was not aware of any American vessel having been condemned in the Vice-Admiralty Court of that colony.

It was true that a barque called the Navarre had been condemned in the court, which might or might not have been American; but the circumstances under which the case was presented to the court, were such as to induce the court to conclude that the Navarre was at the time of seizure not entitled to the protection of any state or nation.

With respect to the commander’s request that he should be furnished with a copy of the affidavits in the case, the judge regretted to state, that with every disposition to comply with his wishes, so far as regards the proceedings of the court, yet as the statement of the commander not only reflected upon the conduct of the officers concerned in the seizure, but involved questions not falling within the province of the court, he did not feel justified in giving any special directions in reference to the application.

Similar reasons were assigned for not furnishing a copy of the affidavits in the case of the Volusia.

In a letter to the commodore, dated October 19th, information was given substantially as follows:

“A few days previously to leaving the coast of Africa, a letter was received from the American consul at Rio, in reply to a communication from the commander of the John Adams, and directed to that office, or to the commander of any U. S. ship-of-war. This letter inclosed a paper containing minutes from the records in the consulate in relation to several American vessels, and among them the barque Navarre and brigantine Volusia were named, as having been furnished with sea-letters as American vessels. These vessels were seized on the coast of Africa, and condemned in this admiralty court, as vessels of unknown nationality.

“Availing himself of the permission to extend the cruise as far as this island, and coming into possession of papers identifying the American nationality of the Navarre and Volusia, the commander regarded it to be his duty to obtain all information in reference to the course pursued by British authorities towards these vessels for the purpose of submitting it to the Government.

“The commander called on the queen’s proctor of the Vice-Admiralty Court, requesting a copy of the affidavits in the instances of the Navarre and Volusia. The proctor stated that the registrar of the court would probably furnish them. The registrar declined doing it without the sanction of the judge, and the judge declined for reasons alleged in the inclosed correspondence.

“The proctor, soon afterwards, placed a packet of papers in the hands of the commander of the Perry, containing the affidavits in question, and requested him to forward them to the British commodore. The proctor suggested to the commander that he might look over the papers. This was declined, on the ground that when the request was made for permission to examine them, unofficially, it was denied, and since having made the request officially for a copy of the papers, they could not now be received and examined at St. Helena, except in an official form. It was then intimated that the intention was to have the papers sent unofficially to the British commodore, that he might show them, if requested to do so, to the American officers.”