CHAPTER THREE

The Medway and its Towns

FROM its position right at the entrance to the River the Medway tributary has always offered a considerable contribution to the defence of London. Going off as it does laterally from the main stream, the Medway estuary has acted the part of a remarkably fine flank retreat. Our forces, driven back at any time to the refuge of the River, could always split up—part proceeding up the main stream towards London, and part taking refuge in the protected network of waterways behind Sheppey and the Isle of Grain. So that the indiscreet enemy, chasing the main portion of the fleet up the estuary of the River, would always be in danger of being caught between two fires. Which fact probably accounts for the tremendous importance with which the Medway has always been regarded in naval and military circles.

Passing between the Isle of Grain and Sheppey, and leaving on our left hand the Swale, in which, so tradition says, St. Augustine baptized King Ethelbert at Whitsun, 596, and on the other bank Port Victoria, the packet-station, we find nothing very striking till we catch sight of Upnor Castle, on the western bank of the river, facing the Chatham Dockyard Extension. This queer old, grey-walled fortress with its cylindrical towers, built in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, is not a very impressive place. It does not flaunt its strength from any impregnable cliff, or even fling defiance from the top of a little hill. Instead, it lies quite low on the river bank. Yet it has had one spell of real life as a fortress, a few days of activity in that inglorious time with which the tributary will ever be associated—the days of “the Dutch in the Medway,” when de Ruyter and van Ghent came with some sixty vessels to the Nore and in about two hours laid level with the ground the magnificent and recently-erected fortifications of Sheerness. This and the happenings of the next few weeks formed, as old John Evelyn says in his “Diary,” “a dreadfull spectacle as ever Englishman saw, and a dishonour never to be wiped off!”

In the pages of Charles Macfarlane’s story, “The Dutch in the Medway,” is to be found a most interesting account of these calamitous days, from which we cull the following extracts: “On the following morning—the memorable morning of the 12th of June—a very fresh wind from the north-east blew over Sheerness and the Dutch fleet, and a strong spring-tide set the same way as the wind, raising and pouring the waters upward from the broad estuary in a mighty current. And now de Ruyter roused himself from his inactivity, and gave orders to his second in command, Admiral van Ghent, to ascend the river towards Chatham with fire-ships, and fighting ships of various rates. Previously to the appearance of de Ruyter on our coasts, his Grace of Albemarle had sunk a few vessels about Muscle Bank, at the narrowest part of the river, had constructed a boom, and drawn a big iron chain across the river from bank to bank, and within the boom and chain he had stationed three king’s ships; and having done these notable things, he had written to Court that all was safe on the Medway, and that the Dutch would never be able to break through his formidable defences. But now van Ghent gave his Grace the lie direct; for, favoured by the heady current and strong wind, the prows of his ships broke through the boom and iron chain as though they had been cobwebs, and fell with an overwhelming force upon the ill-manned and ill-managed ships which had been brought down the river to eke out this wretched line of defence. The three ships, the Unity, the Matthias, and the Charles V., which had been taken from the Dutch in the course of the preceding year—the Annus Mirabilis of Dryden’s flattering poem—were presently recaptured and burned under the eyes of the Duke of Albemarle, and of many thousands of Englishmen who were gathered near the banks of the Medway.

“On the following morning (Thursday, the 13th of June) at about ten o’clock, as the tide was rising, and the wind blowing right up the river, van Ghent, who had been lying at anchor near the scene of his yesterday’s easy triumph, unfurled his top-sails, called his men to their guns, and began to steer through the shallows for Chatham.

“The mid-channel of the Medway is so deep, the bed so soft, and the reaches of the river are so short, that it is the safest harbour in the kingdom. Our great ships were riding as in a wet dock, and being moored to chains fixed to the bottom of the river, they swung up and down with the tide. But all these ships, as well as many others of lower rates, were almost entirely deserted by their crews, or rather by those few men who had been put in them early in the spring, rather as watchmen than as sailors; some were unrigged, some had never been finished, and scarcely one of them had either guns or ammunition on board, although hurried orders had been sent down to equip some of them and to remove others still higher up the river out of the reach of danger.

“It was about the hour of noon when van Ghent let go his anchor just above Upnor Castle. But his fire-ships did not come to anchor. No! Still favoured by wind and tide, they proceeded onward, and presently fell among our great but defenceless ships. The two first of these fire-ships burned without any effect, but the rest that went upward grappled the Great James, the Royal Oak, and the Loyal London, and these three proud ships which, under other names, and even under the names they now bore, had so often been plumed with victory, lay a helpless prey to the enemy, and were presently in a blaze.

“Having burned to the water’s edge the London, the James, and the Royal Oak, and some few other vessels of less note, van Ghent thought it best to take his departure. Yet, great as was the mischief he had done, it was so easy to have done a vast deal more, that the English officers at Chatham could scarcely believe their own eyes when they saw him prepare to drop down the river with the next receding tide, and without making any further effort ... the trumpeters on their quarter decks playing ‘Loth to depart’ and other tunes very insulting and offensive to English pride.”

What shall we say of Chatham, Rochester, and the associated districts of Stroud and New Brompton? It is difficult, indeed, to find a great deal that is praiseworthy. They may perhaps still be summed up in Mr. Pickwick’s words: “The principal productions of these towns appear to be soldiers, sailors, Jews, chalk, shrimps, officers, and dockyard men.”

Formerly the view from the heights of Chatham Hill must have been a splendid one, with the broad Medway and its vast marshlands stretching away for miles across to the wooded uplands of Hoo. Now it appears almost as if a large chunk of the crowded London streets had been lifted bodily and dropped down to blot out the beauties of the scene, for there is little other to be seen than squalid buildings huddled together in mean streets, with just here and there a great chimney-stack to break the monotony of the countless roofs.

The dockyard at Chatham is much the same as any other dockyard, and calls for no special description. From its slips have been launched many brave battleships, right down from the days of Elizabeth to our own times. Here at all seasons may be seen cruisers, battleships, destroyers, naval craft of all sorts, dry docked for refitting. All day long the air resounds to the noise of the automatic riveter, and the various sounds peculiar to a shipbuilding area.

For many years the dockyard was associated with the name of Pett, a name famous in naval matters, and it was on one member of the family, Peter Pett, commissioner at Chatham, that most of the blame for the unhappy De Ruyter catastrophe most unjustly fell. Somebody had to be the scapegoat for all the higher failures, and poor Pett went to the Tower. But not all people agreed with the choice, as we may see from these satirical lines which were very popular at the time:

“All our miscarriages on Pett must fall;

His name alone seems fit to answer all.

Whose Counsel first did this mad War beget?

Who would not follow when the Dutch were bet?

Who to supply with Powder did forget

Languard, Sheerness, Gravesend and Upnor? Pett.

Pett, the Sea Architect, in making Ships

Was the first cause of all these Naval slips;

Had he not built, none of these faults had bin:

If no Creation, there had been no Sin.”

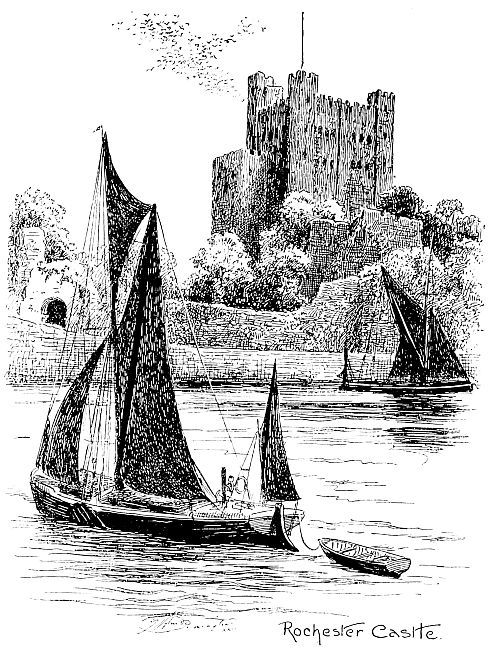

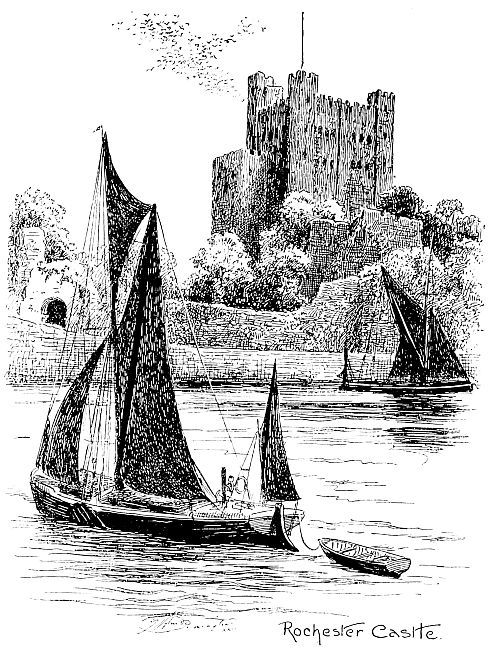

Rochester Castle.

The river here is a very busy place, and is under certain circumstances quite picturesque. There is a weird blending of ancient and modern, of the dimly-comprehended past and the blatant, commercial present, along Limehouse Reach, with its tremendous coal-hoists, and its smoking stacks, and its brown-sailed barges and snorting tugs—with the great masses of Rochester Castle and Cathedral looming out behind it all.

Limehouse Reach is, indeed, an appropriate name, for all along this part, especially in the suburbs of Stroud and Frindsbury, the lime and cement-making industries are carried on extensively. Throughout a great deal of its length the Medway Valley is scarred by great quarries cut into the chalk hills; for it is chalk and the river mud, mixed roughly in the proportion of three to one and then burned in a kiln, which give the very valuable Portland cement, an invention now about a century old.

Rochester Cathedral

Rochester itself is a quaint old place, standing on the ancient Roman road from Dover to London, and guarding the important crossing of the Medway. It can show numbers of Roman remains in addition to its fine old Norman castle, and its Cathedral with a tale of eight centuries. The town stands to-day much as it stood when Dickens first described it in his volumes. The Corn Exchange is still there—“oddly garnished with a queer old clock that projects over the pavement out of a grave, red-brick building, as if Time carried on business there, and hung out his sign;” and so are Mr. Pickwick’s “Bull Hotel,” and the West Gate (Jasper’s Gateway), and Eastbury House (Nuns’ House) of “Edwin Drood”; also the famous house of the “Seven Poor Travellers.”