CHAPTER FOUR

Gravesend and Tilbury

THE dreary fenland district which stretches from the Isle of Grain inland to Gravesend is that so admirably used by Dickens for local colour in his novel, “Great Expectations.” Some of his descriptions of the scenery in this place of “mudbank, mist, swamps, and work” cannot be bettered.

Here is Cooling Marsh with its quaint, fourteenth-century relic, Cooling Castle Gatehouse, built at the time of the Peasants’ Revolt, when the rich folk of the land found it expedient to do little or nothing to aggravate the peasantry. The builder, Sir John de Cobham, realizing the danger, saw fit to attach to one of the towers of his stronghold a plate, to declare to all and sundry that there was in his mind no thought other than that of protection from some anticipated foreign incursions. This plate is still in position on the ruin, and reads:

“Knowyth that beth and schul be

That I am mad in help of the cuntre

In knowyng of whyche thyng

Thys is chartre and wytnessynge.”

According to Dr. J. Holland Rose, the authority on Napoleonic subjects, it was at a spot somewhere along this little stretch that Napoleon at the beginning of the last century proposed to land one of his invading columns. Other columns would land at various points on the Essex and Kent coasts, and all would then converge on London, the main objective. In fact, the Thames Estuary was such a vulnerable point that it occupied a considerable position in the scheme of defence drawn up for Pitt by the Frenchman Dumouriez.

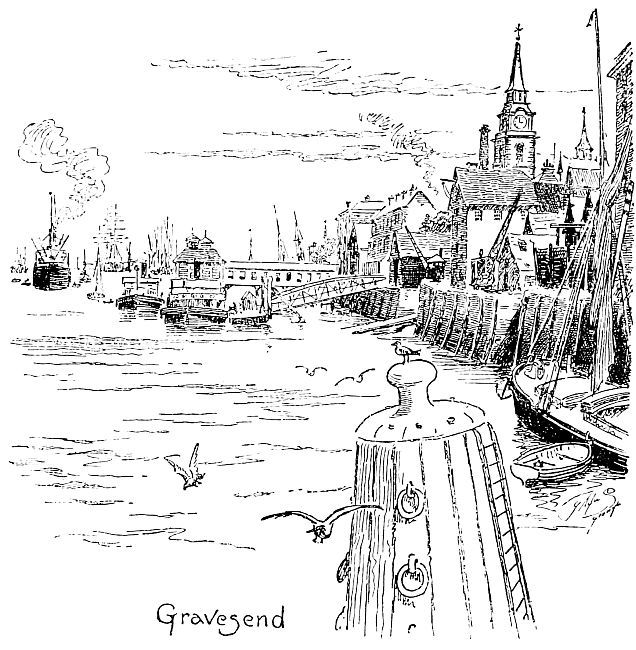

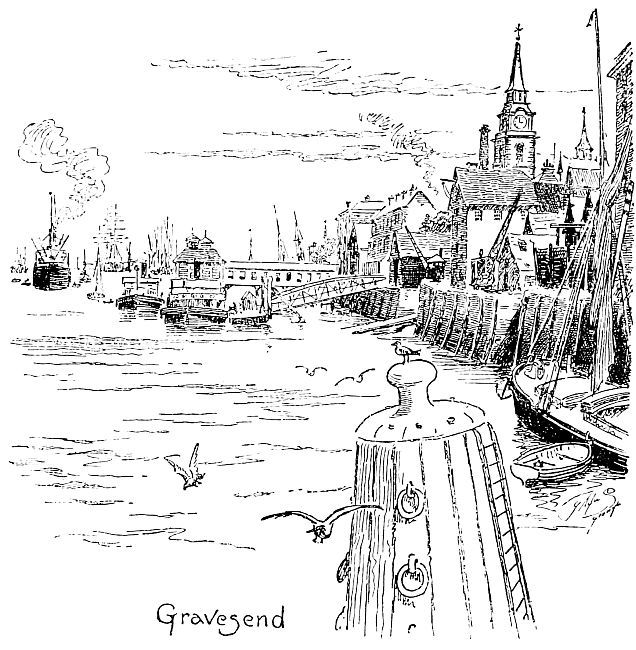

Gravesend itself from the River is not by any means an ill-favoured place, despite its rather commercial aspect. Backed by the sloping chalk hills, and with a goodly number of trees breaking up the mass of its buildings, it presents a tolerably picturesque appearance. Particularly is it a welcome sight to those returning to England after a long voyage, for it is frequently the first English town seen at all closely.

Gravesend

At Gravesend the ships, both those going up and those going down, take aboard their pilots. The Royal Terrace Pier, which is the most prominent thing on Gravesend river front, is the headquarters of the two or three hundred navigators whose business it is to pilot ships to and from the Port of London, or out to sea as far as Dungeness on the south channel, or Orfordness, off Harwich, on the north channel. These men work under the direction of a “ruler,” who is an official of Trinity House, the corporation which was founded at Deptford in the reign of Henry VIII., and which now regulates lighthouses, buoys, etc.

Gravesend is famous for two delicacies, its shrimps and its whitebait, and the town possesses quite a considerable shrimp-fishing fleet.

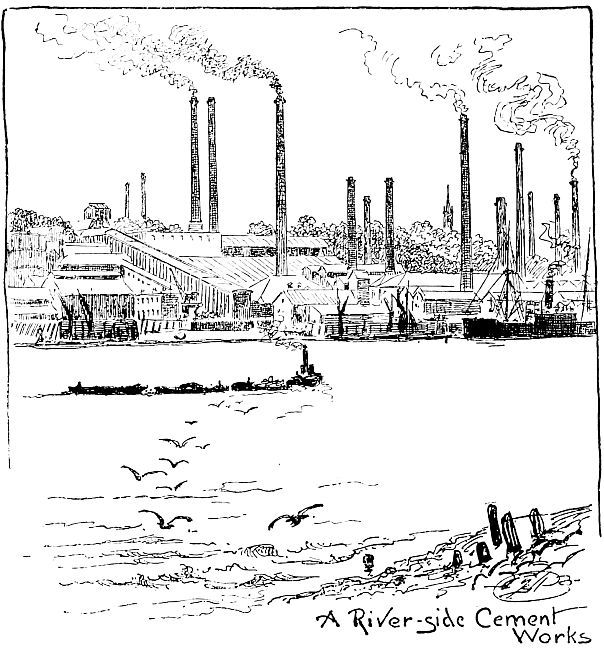

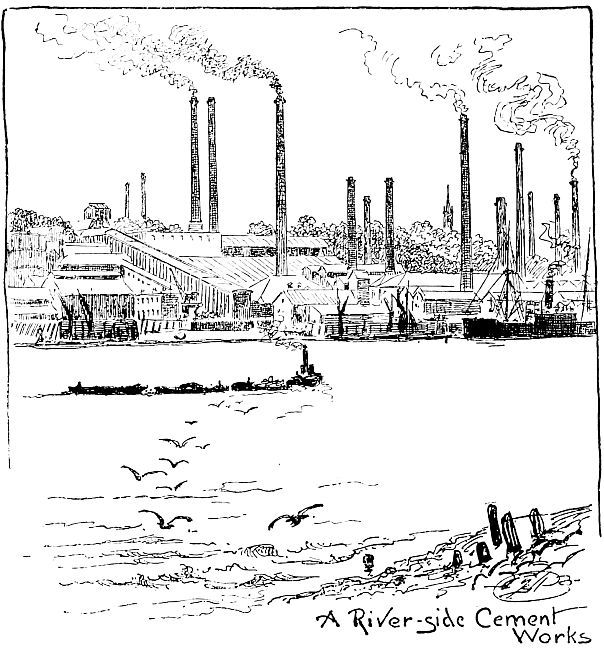

As in the Medway Valley, the cement works form a conspicuous feature in the district round about. In fact, all this stretch, where the chalk hills crop out towards the River’s edge, has been famous through long years for the quarrying of chalk and the making of lime, and afterwards cement. As long ago as Defoe’s time we have that author writing: “Thus the barren soil of Kent, for such the chalky grounds are esteemed, make the Essex lands rich and fruitful, and the mixture of earth forms a composition which out of two barren extremes makes one prolific medium; the strong clay of Essex and Suffolk is made fruitful by the soft meliorating melting chalk of Kent which fattens and enriches it.”

A River-side Cement Works

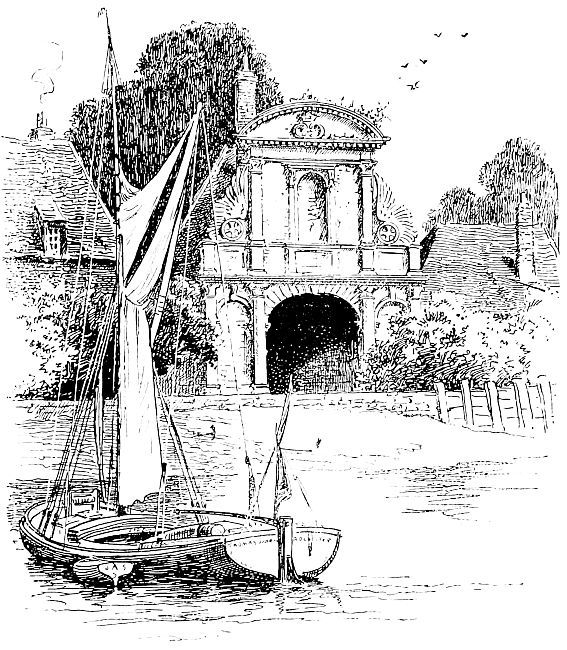

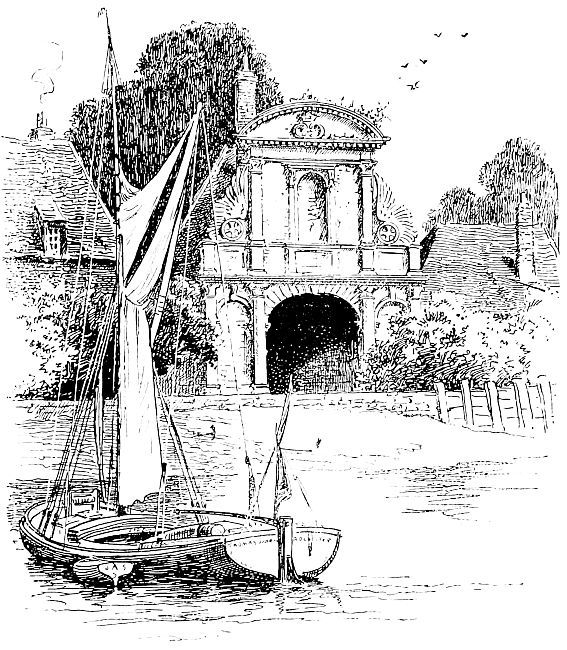

On the Essex coast opposite Gravesend are the Tilbury Docks and the Tilbury Fort—eloquent reminders of the present and the past. At the Fort the ancient and the new lie in close proximity, the businesslike but obsolete batteries of modern times keeping company with the quaint old blockhouse, which at one time formed such an important point in the scheme of Thames defence.

This old Tilbury Fort, with its seventeenth-century gateway, has been so frequently painted that many folk who have never seen it are quite familiar with its outline. At the beginning of the fifteenth century the folk of Tilbury, realizing how vulnerable their settlement was, set to work to fortify it, and later Henry VIII. built a blockhouse here, probably on the site of an ancient Roman encampment. This, when the Spanish Armada threatened, was altered and strengthened by Gianibelli, the clever Italian engineer. Hither Elizabeth came, and, so tradition says, made a soul-stirring speech to her soldiers:

THE GATEHOUSE, TILBURY FORT.

“My loving people, we have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit ourselves to armed multitudes for fear of treachery. But I assure you, I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear. I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and goodwill of my subjects. And therefore I am come among you at this time, not as for any recreation or sport, but being resolved, in the midst of the heat and the battle, to live or die amongst you all; to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and for my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust. I know I have but the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart of a king, and of a king of England, too; and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm. To which, rather than any dishonour should grow by me, I myself will take up arms; I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.”

She had need to feed them on words, for by reason of her own meanness and procrastination the poor wretches had empty stomachs, or would have had if the citizens of London had not loyally come to the assistance of their soldiers. In any case Elizabeth’s exertion was quite unnecessary, for the winds and the waves had conspired to do for England what the Queen’s niggardliness might easily have prevented our brave fellows from doing.

An earlier and no less interesting drama was enacted at Tilbury and Gravesend in the reign of Richard II. Close in the train of that national calamity, the Black Death, came in not unnatural consequence the outbreak known as the Peasants’ Revolt. Just a short way east of Tilbury, at a little village called Fobbing, broke out Jack Straw’s rising; and almost simultaneously came the outburst of Wat Tyler, when the Kentish insurgents marched on Canterbury, plundered the Palace, and dragged John Ball from his prison; then moved rapidly across Kent, wrecking and burning. At Tilbury and Gravesend these two insurgent armies met, and thence issued their summons to the King to meet them. He, brave lad of fifteen, entered his barge with sundry counsellors, and made his way downstream. How he met the disreputable rabble, and how the peasants were enraged because he was not permitted to land and come among them, is a well-known story, as is the furious onslaught on London which resulted from the refusal.

Thus far up the River came the Dutch in those terrible days of which we read in our last chapter. They sailed upstream on the day of their arrival, firing guns so that the sound was heard in the streets of London, but they came to a halt slightly below the point where the barricade, running down into the water from the Essex shore, largely closed up the waterway, and where the little Fort frowned down on the intruders. No attempt was made to stay them; indeed, none could have been made, for while the little blockhouse was well provided with guns, it was practically without powder; and the invaders could have proceeded right into the Pool of London without hindrance had they but known it. However, they were content for the time being with merely frightening the countryside with their terrible noise. As Evelyn says in his “Diary” (June 10): “The alarm was so great that it put both country and city into a panic, fear and consternation, such as I hope I shall never see more; everybody was flying, none knew why or whither.” Having done this, the Dutch passed downstream to Sheerness, where their companions were engaged in destroying the fortifications. How long they stayed in these parts may be judged by this other extract from Evelyn, dated seven weeks after (July 29): “I went to Gravesend, the Dutch fleet still at anchor before the river, where I saw five of His Majesty’s men-of-war encounter above twenty of the Dutch, in the bottom of the Hope, chasing them with many broadsides given and returned towards the buoy of the Nore, where the body of their fleet lay, which lasted till about midnight.... Having seen this bold action, and their braving us so far up the river, I went home the next day, not without indignation at our negligence, and the Nation’s reproach.”

In 1904 it was proposed in the House of Commons that there should be made at Gravesend a great barrage or dam, right across the River Thames, with a view to keeping a good head of water in the stream above Gravesend, much as the half-tide lock (about which we shall read in Book III.) does at Richmond. This, the proposers said, would do away with the cost of so much dredging, and would make the building of riverside quays a much simpler and more satisfactory matter, for by it the whole length of river between Gravesend and London would be to all intents converted into one gigantic dock-basin. It was proposed that the barrage should have in it four huge locks to cope with the large amount of shipping, also a road across the top and a railway tunnel underneath. But many weighty objections were urged, and numerous difficulties were pointed out, so that the scheme fell through; and so far the only semblance of a barrage known to Gravesend has been that which was thrown right across the lower River for defensive purposes during the Great War.