CHAPTER EIGHT

The Port and the Docks

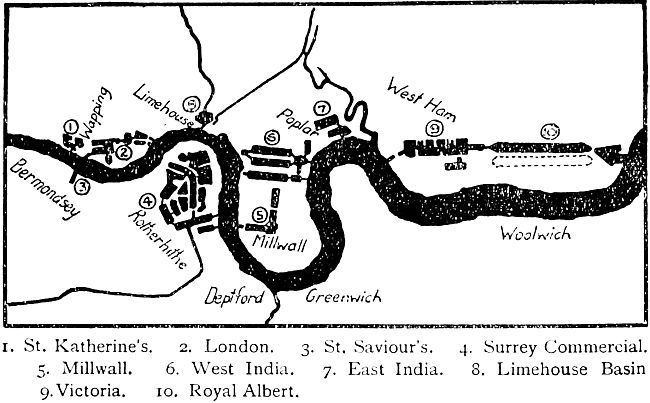

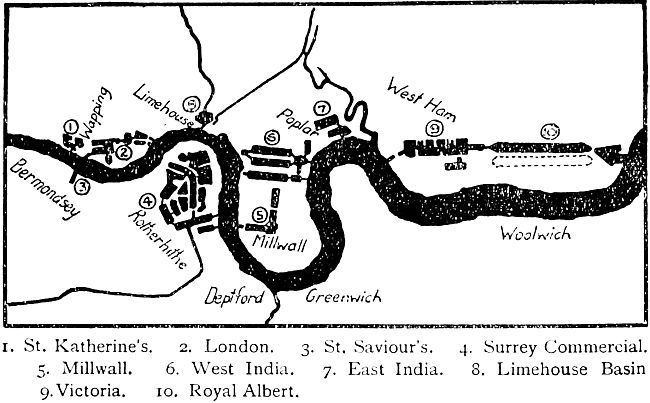

ANY person standing on London Bridge a couple of centuries ago would have observed a scene vastly different from that of to-day. Now we see the blackened line of wharves and warehouses on the two banks, and up against them steamers discharging or receiving their cargoes, while out in the stream a few vessels of medium size and one or two clusters of barges lie off, awaiting their turn inshore; otherwise the wide expanse of the stream is bare, save for the occasional craft passing up and down in the centre of the stream. But in days gone by, as we can tell by glancing at the pictures of the period, the River was simply crowded with ships of all kinds, anchored closely together in the Pool, while barges innumerable plied between them and the shore.

In very early days only Billingsgate and Queenhithe possessed accommodation for ships to discharge and receive their cargoes actually alongside the quay; for the most part ships berthed out in the stream, and effected the exchange of goods by means of barges.

Then, as trade increased by leaps and bounds, a number of “legal quays” were instituted between London Bridge and the Tower, and thither came the major part of the merchandise. Gradually little docks or open harbours were cut into the land in order to relieve the congestion of the quays. Billingsgate was the first of these, and for many years the most important. Now the dock has for the most part been filled in, and over it has been erected the famous fish-market, which still carries on one of the main trades of the little ancient dock. Others were St. Katherine’s Dock, a tiny basin formed for the landing of the goods of the monastery which stood hard by the Tower; St. Saviour’s Dock in Bermondsey on the Surrey side; and Execution Dock close to Wapping Old Stairs.

However, with the tremendous growth of trade following the Great Fire of London, concerning which we shall read in Book II., and with the growth in the size of vessels and the consequent increase in the difficulties of navigation, the facilities for loading and unloading proved totally inadequate, and the merchants were led to protest, on the grounds that the overcrowding led to great confusion and many abuses, and for a great number of years they entreated Parliament to take some action.

DOCKLAND.

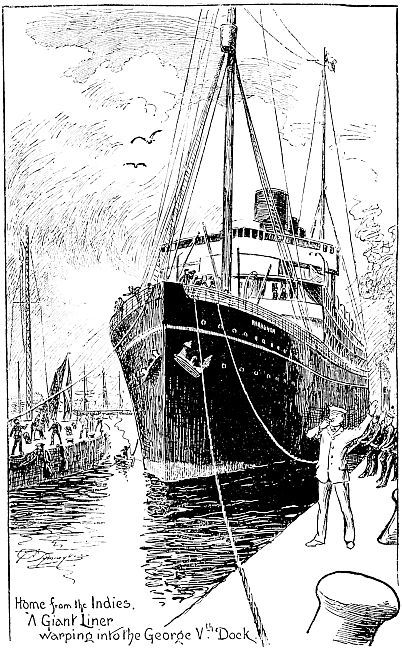

The coming of the great docks ended the trouble, and also tremendously changed the Port of London. When the West India Docks were opened in 1802, ships concerned with the transport of certain articles of commerce were no longer allowed to lie in the Pool for the purpose of discharge: they were compelled to go to the particular dock-quays set aside for their use, and to land there the merchandise they carried. Thus practically at a stroke of the pen the riverside wharves lost their entire traffic in such things as sugar, rum, brandy, spices, and other goods from the West Indies. Similarly, when the East India Docks were opened all the commerce of the East India Company was landed there. Thus, gradually, as the various larger docks were made from time to time, the main business of the Port shifted eastwards to Millwall, Blackwall, etc. Nor did it stop there. With the coming of ships larger even than those already catered for, it became necessary to do something to avoid the passage of the shallow, winding reaches above Gravesend, and, in consequence, tremendous docks were opened at Tilbury. So that now vessels of the very deepest draught enter and leave the docks independent of the tidal conditions, and do not come within many miles of London Bridge.

This does not mean that the riverside wharves and warehouses were rendered useless by the shifting of the Port. So great had been the congestion that even with the relief of the new docks there was still—and there always has been—plenty for them to do. To-day there are miles of private wharves in use: from Blackfriars down to Shadwell the River is lined with them on both sides all the way; and they share with the great docks and dock warehouses the vast trade of the Port of London.

Let us take a short trip down through dockland, and see what this romantic place has to show us. We must go by water. That is essential if we are to see anything at all, for so shut in is the River by tall warehouses, etc., that we might wander for hours and hours in the streets quite close to the shore, and yet never catch a glimpse of the water.

Leaving Tower Bridge, we find immediately on our left the St. Katherine’s Docks. These get their name from the venerable foundation which formerly stood on the spot. This religious house was created and endowed by Maud of Boulogne, Queen of Stephen, and lasted through seven centuries down to about a hundred years ago. It survived even the Dissolution of the Monasteries, which swept away all other London foundations, being regarded as more or less under the protection of the Queen. Yet this wonderful old foundation, with its ancient church, its picturesque cloisters and schools, its quaint churchyard and gardens—one of the finest mediæval relics which London possessed—was completely destroyed to make way for a dock which could have been constructed just as well at another spot. London knows no worse example of needless, stupid, brutal vandalism! St. Katherine’s Dock is concerned largely with the import of valuable articles: to it come such things as China tea, bark, india-rubber, gutta-percha, marble, feathers, etc.

London generally is the English port for tea: hither is brought practically the whole of the country’s consumption. During the War efforts were made to spread the trade more evenly over the different large ports; but the experiment was far from a success. All the vast and intricate organization for blending, marketing, distributing, etc., is concentrated quite close to St. Katherine’s Dock, and in consequence the trade cannot be managed so effectively elsewhere. The value of the tea entering the Port of London during 1913, the year before the War, and therefore the last reliable year for statistics, was nearly £13,500,000.

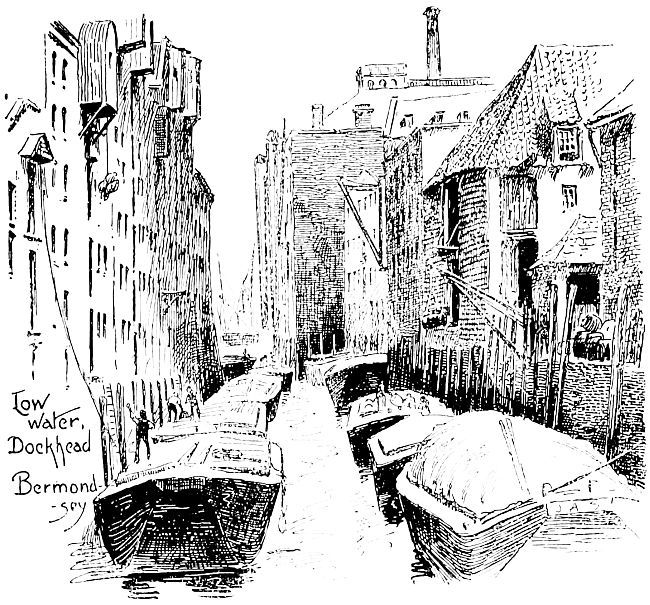

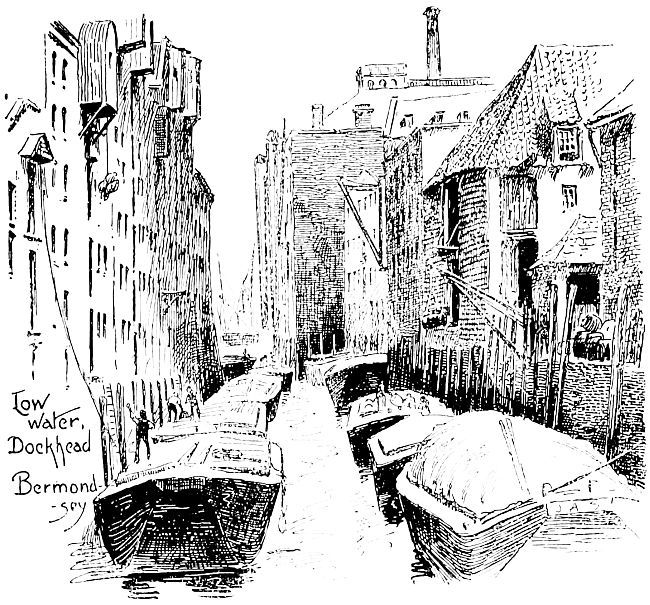

Low water, Dockhead Bermondsey

A little below St. Katherine’s, on the Surrey shore, is one of the curiosities of dockland—a dock which nobody wants. This is St. Saviour’s Dock, Bermondsey—a little basin for the reception of smaller vessels. It is disowned by all—by the Port of London Authority, by the Borough Council, and by the individual firms who have wharves and warehouses in the vicinity. You see, there is at one part of the dock a free landing-place, to which goods may be brought without payment of any landing-dues; and no one wants to own a dock without full rights. Shackleton’s Quest berthed here while fitting out for its long voyage south.

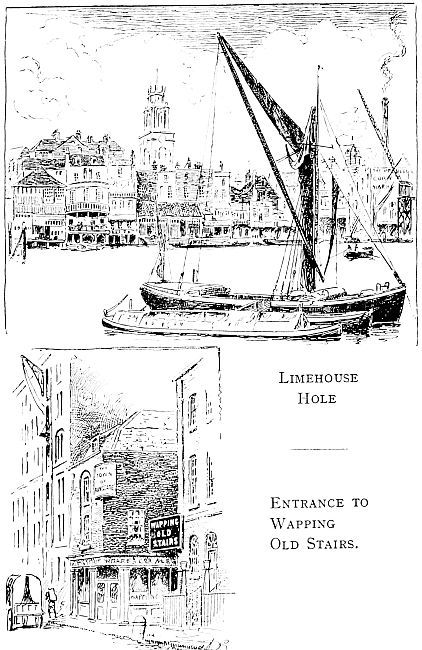

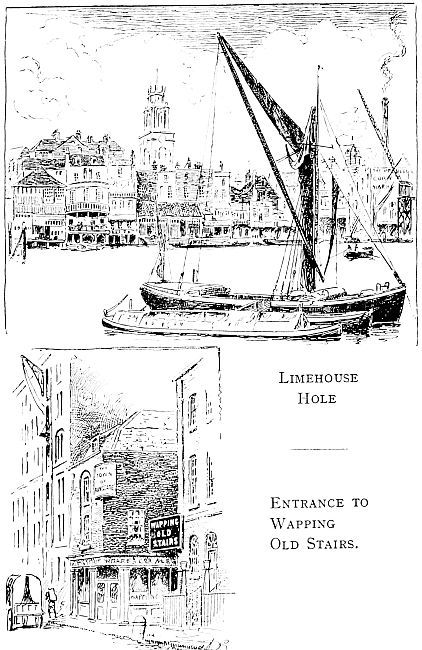

From St. Katherine’s onward for several miles the district on the north bank is known as Wapping. This was for many years the most marine of all London’s riverside districts. Adjoining the Pool, it became, and remained through several centuries, the sojourning-place of “those who go down to the sea in ships.” Here, at famous Wapping Old Stairs or one of the other landing-steps which ran down to the water’s edge at the various quay-ends, Jack [109]

[110]said good-bye to his sweetheart as he jumped into one of the numerous watermen’s boats, and was rowed to his ship lying out in the stream; here, too, there waited for Jack, as he came home with plenty of money, all those crimps and vampires whose purpose it was to make him drunk and rob him of all his worldly goods. Harbouring, as it did, numbers of criminals of the worst type, Wapping for many years had a very bad name. Now all that has changed. The shifting of the Port deprived the sharks of their victims, for the seamen no longer congregated in this one area: they came ashore at various points down the River. Moreover, the making of the St. Katherine and later the London Docks cut out two big slices from the territory, with a consequent destruction of mean streets.

LIMEHOUSE HOLE.

ENTRANCE TO WAPPING OLD STAIRS.

Close to Wapping Old Stairs was the famous Execution Dock. This was the spot where pirates, smugglers, and sailors convicted of capital crimes at sea, were hanged, and left on the foreshore for three tides as a warning to all other watermen. Now, with the improvements at Old Gravel Lane, all traces have vanished, and the wrong-doers no longer make that last wretched journey from Newgate to Wapping, no longer stop half-way to consume that bowl of pottage for which provision was made in the will of one of London’s aldermen.

The goods which enter London Dock are of great variety—articles of food forming a considerable proportion.

Limehouse follows on the northern shore, and is perhaps, even more than Wapping, the marine district of these days. Here, in a place known as the Causeway, is the celebrated Chinese quarter. Regent’s Canal Dock, which includes the well-known Limehouse Basin, a considerable expanse of water, is the place where the Regent’s Canal begins its course away to the midlands. The chief goods handled at Limehouse Basin were formerly timber and coal, but since the War this has become the centre for the German trade. Here are frequently to be seen most interesting specimens of the northern “wind-jammers.”

Leaving Limehouse, the River sweeps away southwards towards Greenwich, and then turns sharply north again to Blackwall. By so doing it forms a large loop in which lies the peninsula known as the Isle of Dogs—a place which has been reclaimed from its original marshy condition, and covered from end to end with docks, factories, and warehouses, save at the southernmost extremity, where the London County Council have made a fine riverside garden. In the Isle are to be found the great West India Docks and the Millwall Docks. The former receive most of the furniture woods—mahogany, walnut, teak, satin-wood, etc.—and also rum, sugar, grain, and frozen meat; while the latter receive largely timber and grain.

On the Surrey side of the River, practically opposite the West India and Millwall Docks, are the Surrey Commercial Docks, occupying the greater portion of a large tongue of land in Rotherhithe. To these docks come immense quantities of timber, grain, cattle, and hides—the latter to be utilized in the great tanning factories for which Bermondsey is famous.

Blackwall, the last riverside district within the London boundary, is famous for its tunnel, which passes beneath the bed of the River to Greenwich. This is but one of a number of tunnels which have been made beneath the stream in recent years. There is another for vehicles and passengers passing across from Rotherhithe to Limehouse, while further upstream are those utilized by the various tube-railways in their passage from north to south.

Blackwall has a number of docks, large and small. Among the latter are several little dry-docks which exist for the overhauling and repairing of vessels. There was a time when shipbuilding and ship-repairing were considerable industries on the Thames-side, when even battleships were built there, and thousands of hands employed at the work; but the trade has migrated to other dockyard towns, and all that survive now are the one or two repairing docks at Blackwall and Millwall.

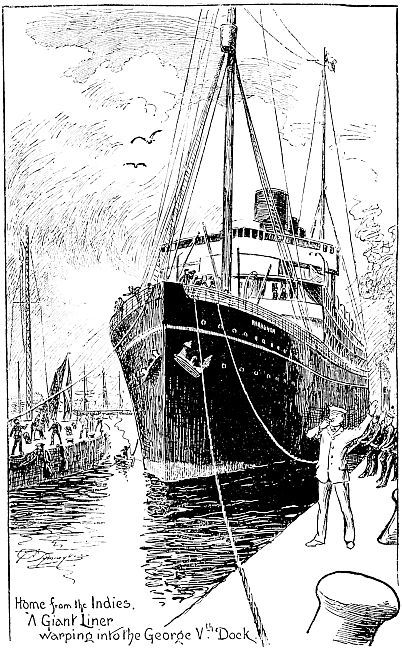

The Royal Albert and the Victoria Docks come within the confines of those great new districts, West Ham and East Ham, which have during the last thirty or forty years sprung up, mushroom-like, from the dreary flats of East London. Here are such well-known commercial districts as Silvertown and Canning Town. The former will doubtless be remembered through many years for the tremendous explosion which occurred there during the War—an explosion which resulted in serious loss of life and very great damage to property. It is also famous for several great factories, notably Messrs. Knight’s soap-works, Messrs. Henley’s cable and general electrical works, and Messrs. Lyle’s (and Tate’s) sugar refineries. These places, which employ thousands of hands, are of national importance.

Canning Town has to some extent lost its prestige, for it was in time past the shipbuilding area. Here were situated the great Thames Ironworks, carrying on a more or less futile endeavour to compete with the Clyde and other shipbuilding districts.

This district is, to a large extent, the coal-importing area. Coal is the largest individual import of the Port of London, as much as eight million tons entering in the course of a year. The chief articles of commerce with which the Royal Albert and Victoria Docks are concerned are: Tobacco, frozen meat, and Japanese productions.

Vast, indeed, have been the revenues drawn from the various docks. You see, goods are not entered or dispatched except on payment of various dues and tolls, and these amount up tremendously. So that the Dock Companies get so much money from the thirty miles of dockside quays and riverside wharves that they scarcely know what to do with it, for the amount they can pay away in dividends to their shareholders is strictly limited by Act of Parliament. In one year, for instance, so large a profit was made by the owners of the East and West India Docks that they used up an enormous sum of money in roofing their warehouses with sheet copper.

In concluding our rapid tour through dockland, it is impossible to omit a reference to the Customs Officers—those cheery young men who work in such an atmosphere of unsuspected romance. To spend a morning on the River with one of them, as he goes his round of inspection of the various vessels berthed out in the stream, is a revelation. To visit first this ship and then the other; to see the amazing variety of the cargoes, the number of different nationalities represented, both in ships and men; to come into close touch with that strange and little-understood section of the community, the lightermen, whose work is the loading of the barges that cluster so thickly round the great hulls—is to move in a world of dreams. But to go back to the Customs Offices and see the huge piles of documents relating to each single ship that enters the port, and to be informed that on an average two hundred ocean-going ships enter each week, is to experience a rude awakening from dreams, and a sharp return to the very real matters of commercial life.

Home From the Indies. A Giant Liner warping into the George Vth. Dock.

Nor must we forget the River Police, who patrol the River from Dartford Creek up as far as Teddington. As we see them in their launches, passing up and down the stream, we may regard their work as easy; but it is anything but that—especially at night-time. Then it is that the river-thieves get to work at their nefarious task of plundering the valuable cargoes of improperly attended lighters. The River Police must be ever on the alert, moving about constantly and silently, lurking in the shadows ready to dash out on the unscrupulous and dangerous marauders. The headquarters of the River Police are at Wapping, but there are other stations at Erith, Blackwall, Waterloo, and Barnes.

In 1903 the question of establishing one supreme authority to deal with all the difficulties of dockland and take control of practically the whole of the Port of London was discussed in Parliament, and a Bill was introduced, but owing to great opposition was not proceeded with. However, the question recurred from time to time, and in 1908 the Port of London Act was at length passed.

This established the Port of London Authority, for the purpose of administering, preserving, and improving the Port of London. The limits of the Authority’s power extend from Teddington down both sides of the River to a line just east of the Nore lightship. At its inception the Authority took over all the duties, rights, and privileges of the Thames Conservancy in the whole of this area.