CHAPTER SEVEN

Greenwich

THE history of towns no less than the history of men can tell strange tales of failure and success. Some have had their era of intoxicating splendour, have been beloved of kings and commoners alike, have counted for much in the great struggles with which our tale is punctuated, and then, their little day over, have shrunk to the merest vestige of their former glory. Others, unknown and insignificant villages throughout most of the story, have sprung up, mushroom-like, almost in a night, and entered suddenly and confidently into the affairs of the nation.

In the former class must, perhaps, be counted Greenwich. True, it has not had the disastrous fall, the unspeakable humiliation, of some English towns—Rye and Winchelsea on the south coast, for instance—yet over Greenwich now might well be written that word “Ichabod”—“The glory is departed.” For Greenwich to-day, apart from its two places of outstanding interest, the Hospital and the Park with its Observatory, is largely an affair of mean streets, a collection of tiny, uninteresting shops and drab houses. Yet Greenwich was for long a place of great fame, to which came kings and courtiers, for here was that ancient and glorious Palace of Placentia, a strong favourite with numbers of our monarchs.

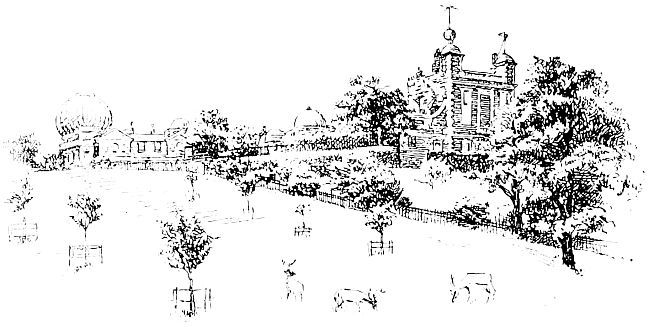

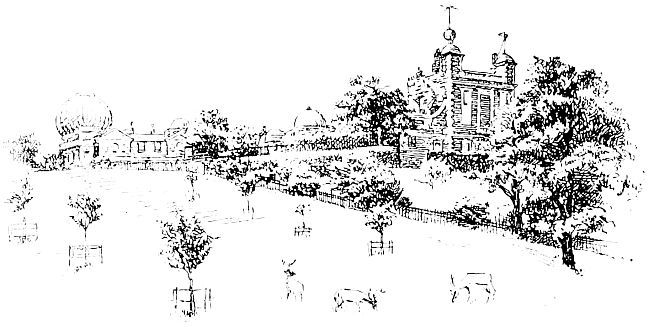

GREENWICH PARK.

Really it began its life as a Royal demesne in the year 1443, when the manor was granted to Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and permission given for the fortification of the building and enclosing of a park of two hundred acres. The Duke interpreted his permission liberally, and erected a new palace, to which he gave the name of Placentia, the House of Pleasance. He formed the park, and at the summit of the little hill, one hundred and fifty feet or more above the River, constructed a tower on the identical spot where the Observatory now stands. On Humphrey’s death the Crown once more took charge of the property. Edward IV. spent great sums in beautifying it, so that it was held in the highest esteem by the monarchs that followed. Henry VII. provided it with a splendid brickwork river front to increase its comeliness.

Here, in 1491, was born Henry VIII., and here he married Katherine of Aragon. Here, too, his daughters, Mary (1515) and Elizabeth (1533), first saw the light. Edward VI., his pious young son, breathed his last within the walls.

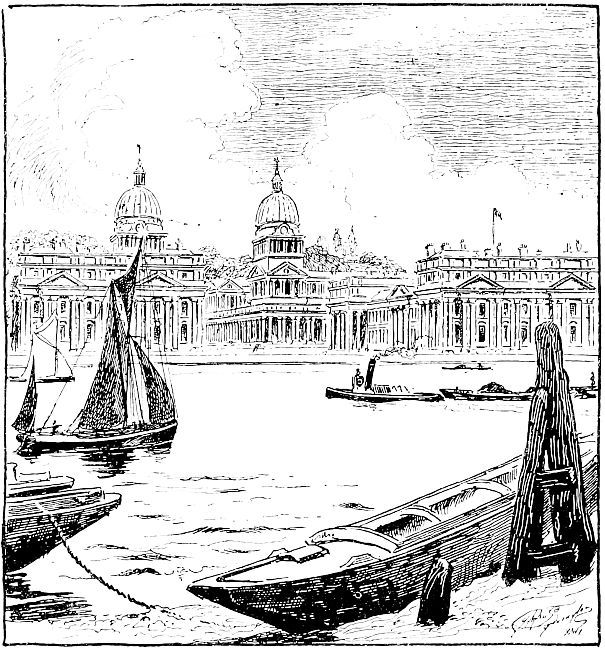

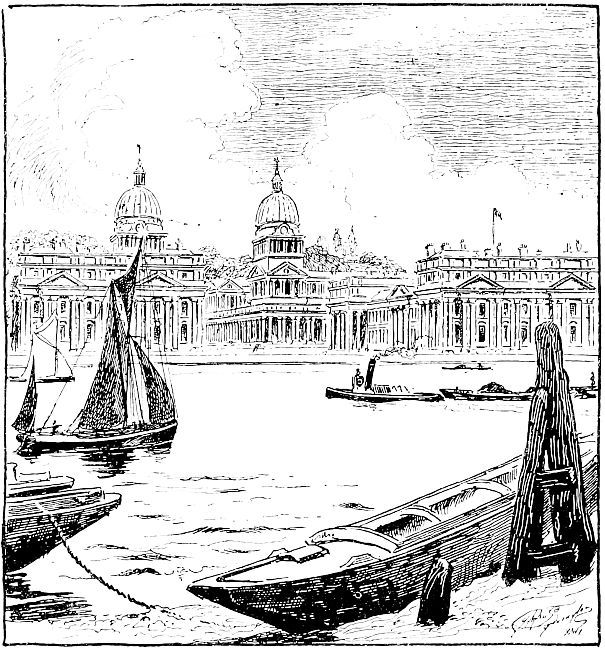

In those days the River banks did not present quite the same commercial aspect as in our own times; the atmosphere was not quite so befouled by the smoke of innumerable chimneys, the water was not quite so muddy; and in consequence the journey by water from the City to that country place, Greenwich, was a little more pleasant. Indeed, it is said that the view up river from Greenwich Park rivalled that from Richmond Hill in beauty. In those days all who could went by water, for the River was the great highway. Then was its surface gay with brightly painted and decorated barges, threading their way downstream among the picturesque vessels of that time.

From Placentia the sovereign could watch the ever-changing but never-ending pageant of the River, see the many great ships bringing in the wealth from all known lands, and watch the few journeying forth in search of lands as yet unknown. Thus on one occasion the occupants viewed the departure of three shiploads of brave mariners setting forth to search for a new passage to India by way of the Arctic regions—a scene which old Hakluyt describes for us: “The greater shippes are towed downe with boates and oares, and the mariners being all apparelled in watchet or skie-coloured cloth rowed amaine and made with diligence. And being come neare to Greenwiche (where the Court then lay) presently upon the newes thereof the courtiers came running out and the common people flockt together, standing very thicke upon the shoare; the privie counsel they lookt out at the windowes of the court and the rest ran up to the toppes of the towers; and shoot off their pieces after the manner of warre and of the sea, insomuch that the toppes of the hilles sounded therewith, the valleys and the waters gave an echo and the mariners they shouted in such sort that the skie rang againe with the noyse thereof. Then it is up with their sails, and good-bye to the Thames.”

Nor in talking of Greenwich must we forget the famous Ministerial fish dinners which were for so many years a great event in the life of the town. This custom arose, it is said, from the coming of the Government Commissioners to examine Dagenham Breach, when they so enjoyed the succulent fare set before them that they insisted on an annual repetition, which function was afterwards transferred to the “Ship” at Greenwich.

At the toe of the great horseshoe bend which gives us Millwall and the Isle of Dogs stands that famous group of buildings known as Greenwich Hospital, but more correctly styled the Greenwich Naval College.

This is built on the site of the old Palace. When, following the Revolution, Charles II. came to the throne, he found the old place almost past repair, so he decided to pull it down and erect a more sumptuous one in its place. Plans were accordingly drawn up by the architect, Inigo Jones, and the building commenced; but only a very small portion—the eastern half of the north-western quarter—was completed during his reign.

It was left to William and Mary, those eager builders, to carry on the work, which they did with the assistance of Sir Christopher Wren, to whose powers of architectural design London owes so much. Very little was done during the life of Queen Mary, but as the idea was hers, William went on with the work quite gladly, as a sort of memorial to his wife.

Of course, a very large sum of money was needed for the erection of such a place. The King himself provided very liberally—a good deed in which he was followed by courtiers and private citizens. But quite a large amount was found in several very interesting ways. Since the buildings were designed to provide a kind of hospital or asylum for aged and disabled seamen who were no longer able to provide for themselves, it was decided to utilize naval funds to some extent. So money was obtained from unclaimed shares in naval prize-money, from the fines which captured smugglers had to pay, and from a levy of sixpence a month which was deducted from the wages of all seamen. Building went on apace, and (to quote Lord Macaulay) “soon an edifice, surpassing that asylum which the magnificent Lewis had provided for his soldiers, rose on the margin of the Thames. Whoever reads the inscription which runs round the frieze of the hall will observe that William claims no part in the merit of the design, and that the praise is ascribed to Mary alone. Had the King’s life been prolonged till the work was completed, a statue of her who was the real founder of the institution would have had a conspicuous place in that court which presents two lofty domes and two graceful colonnades to the multitudes who are perpetually passing up and down the imperial River. But that part of the plan was never carried into effect; and few of those who now gaze on the noblest of European hospitals are aware that it is a memorial of the virtues of the good Queen Mary, and the great victory of La Hogue.”

GREENWICH HOSPITAL.

In 1705 the preparations were complete, and the first pensioners were installed in their new home. The place was very successful at the start, and it grew till at the beginning of the nineteenth century there were nearly three thousand men residing within the Hospital walls, and many more boarded out in the town.

Then through half a century the prosperity of the place began to decline. The old pensioners died off, and the new ones, as they came along, for the most part preferred to accept out-pensions and live where they liked. So that in 1869 it was decided to abandon the place as an asylum for seamen and convert it into a Royal Naval College, in which to give training to the officers of the various branches of the naval services, and also a Naval Museum and a Sailors’ Hospital.

Perhaps one of the most interesting places in the College is the Painted Hall, a part of Wren’s edifice, known as King William’s Quarter. The ceilings of this double-decked dining-hall—the upper part for officers and the lower for seamen—and the walls of the upper part are decorated most beautifully with paintings which it took Sir James Thornhill nineteen years to complete. Around the walls hang pictures which tell of England’s naval glory—pictures of all sizes depicting our most famous sea-fights and portraying the gallant sailors who won them. Naturally Lord Nelson is much in evidence here, and we can see in cases in the upper hall the very clothes he wore when he received that fatal wound in the cockpit of the Victory—the scene of which is depicted on a large canvas on the walls; also in cases his pigtail, his sword, medals, and various other relics.

The Museum is a fascinating place, for it contains what is practically a history of our Navy set out, not in words in a dry book, but in models of ships; and we can study the progress right from the Vikings’ long-boats, with their rows of oars and their shields hanging all round the sides, down to the massive super-dreadnoughts of to-day. Most interesting of all, perhaps, are the great sailing ships—the old “wooden walls of England”—which did so much to establish and maintain our position as a maritime nation—the great three-deckers which stood so high out of the water, and which with their tall masts and gigantic sails looked so formidable and yet so graceful. There in a case is the Great Harry—named after Henry VIII.—a double-decker of fifteen hundred tons burden, with three masts, and carrying seventy-two guns. She was a fine vessel, launched at Woolwich Dockyard in 1515, and was the first vessel to fire her guns from portholes instead of from the deck. In another case is the first steam vessel ever used in the Navy (1830), and a quaint little craft it is.

This is indeed a splendid collection, and we feel as if we could spend hours studying these fascinating little models.

THE ROYAL OBSERVATORY.

On the site of Duke Humphrey’s tower in Greenwich Park is the world-famous Observatory. If you take up your atlas, and look at the map of the British Isles or the map of Europe, you will see that the meridian of longitude (or the line running north and south) marked 0° passes through the spot where Greenwich is shown. This means that all places in Europe to the right or the left—east or west, that is—are located and marked by their distance from Greenwich; and, if for no other reason, this town is because of this fact a very important place in the world.

The Observatory was founded in the reign of Charles II. This monarch had occasion to consult Flamsteed, the astronomer, concerning the simplifying of navigation, and Flamsteed pointed out to him the need for a correct mapping-out of the heavens. As a result the Observatory was built in 1695 in order that Flamsteed might proceed with the work he had suggested.

The Duke’s tower was pulled down, and the new place erected; but it was left to Flamsteed to find his own instruments and pay his own assistants, all out of a salary of one hundred pounds per annum. Consequently, he became so poor that when he died in 1719 his instruments were seized to pay his debts. His successor, Dr. Halley, another famous astronomer, refitted the Observatory, and some of his instruments can be seen there now, though no longer in use, of course.

Few people are allowed inside the Observatory to see all the wonderful telescopes and other instruments there; but there are several things to be seen from the outside, notably the time-ball which is placed on the north-east turret, and which descends every day exactly at one o’clock; also the electric clock with its twenty-four-hours dial.